s he traveled to Persia and Mesopotamia, Ibn Battuta was, for the first time, moving outward from the heart of Dar al-Islam, following its northeastward axis from Makkah.

![The Mongol sack of Baghdad lay almost seven decades in the past when Ibn Battuta first visited the city, and he noted that large sections of it were still “for the most part in ruins,” and most of its madrasas closed. In the city once famed for the globe-spanning inventory of the Bayt al-Hikma, or “House of Wisdom,” there were few libraries left for Ibn Battuta to visit. Yet he also recorded that “there still remain of [Baghdad] 13 quarters, each quarter like a city in itself, with two or three bath-houses, and in eight of them there are congregational mosques.”](images/part2/BATTUTA_9.47307.gif) |

| The Mongol sack of Baghdad lay almost seven decades in the past when Ibn Battuta first visited the city, and he noted that large sections of it were still “for the most part in ruins,” and most of its madrasas closed. In the city once famed for the globe-spanning inventory of the Bayt al-Hikma, or “House of Wisdom,” there were few libraries left for Ibn Battuta to visit. Yet he also recorded that “there still remain of [Baghdad] 13 quarters, each quarter like a city in itself, with two or three bath-houses, and in eight of them there are congregational mosques.” |

Once he had crossed the Tigris near its mouth, he entered a land through which a tribe of fair-skinned conquerors, the Aryans, had passed so long ago that they were now remembered only by the name they left: Iran. What he saw and heard there—the faces, the languages, the style of the minarets, the governments, the arts—were all still Islamic, but this was a different cultural domain within Islamic culture: the land ruled by the Islamized Mongols known as the Ilkhans.

Since 1258, when the Mongols took the city, Baghdad—and much of Iraq to the west—had also been part of the Ilkhanid domains. In the middle of 1327 Ibn Battuta crossed the Tigris again and, via Kufa, arrived in the once-great city.

Fourteenth-century Baghdad was a city where the marketplace of ideas was as rich and as noisy as any other of the suqs. The devastation the Mongols had wrought 69 years earlier was catastrophic, but under Sultan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, the last of "the kings of the Tatars [Mongols] who converted to Islam," Baghdad was attempting to revive the brilliance and prosperity that had characterized it during its Abbasid heyday, roughly from the eighth to the 11th century. That had been a time when, though China's palaces might have been richer and Cordoba's philosophers deeper, Baghdad was still the world's greatest confluence of intellect, commerce, art, trade and religion, the richest volume on history's bookshelf.

Much of Ibn Battuta's account of the city is elegiac, for in his time the western side of the city, where the caliph al-Ma'mun had built the great Bayt al-Hikma ("House of Wisdom") and other monuments, was largely "a vast edifice of ruins." The mantle of greatness—and the caliphate itself—had shifted to Cairo, which the Mongols never reached. Still, for fame, allure and its aura of history, Baghdad was still the Queen of the Tigris, a name to conjure with—so much so that Ibn Juzayy, as he took down Ibn Battuta's account, was moved here to insert into the Rihla several pre-Mongol panegyrics the city had inspired, presumably to impress upon the reader its former glory. As for Ibn Battuta, in addition to describing visits to the mosques and madrasas supported by nobles or by the sultan himself, he faithfully and factually notes Baghdad's bridges, aqueducts, fountains, reservoirs, baths, fortresses, turrets, machicolated walls, palaces, workshops, factories, granaries, mills, caravansaries, hovels and "magnificent bazaars...splendidly laid out."

In the eastern city, where most settlement was concentrated in the early 14th century, the average workmen's houses were humble rectangles of sun-dried brick. Streets were wide enough for two loaded donkeys to pass—the same width in Baghdad as in Seville. Better homes had a courtyard, a water basin or pit well, a shade tree and ornamental plants. Then as now in much of the Islamic world, outward displays of wealth were avoided. From the outside, no door or window revealed or hinted at the status of the inhabitants within.

| Starting about 1260—a generation before Ibn Battuta’s birth—a great rebuilding of Mongol-devastated Persia began. By the time Ibn Battuta arrived there, the city of Tabriz could count at least one truly great son: Rashid al-Din, statesman, administrative reformer and historian. He was of such great political shrewdness that he survived being co-vizier to no fewer than three Ilkhanid sultans. One of them, worried that the Mongols, as they settled in Persia as Muslims, might forget their origins, commissioned him to write a history of the Mongols. That sultan’s successor ordered him to expand it to cover all peoples with whom the Mongols had come in contact. Rashid thus produced what has been called the first true world history, titled Jami‘ al-Tawarikh (Collection of Histories). It covered the entirety of Dar al-Islam, plus China, Tibet, Turkey, Byzantium, and non-Muslim Western Europe, as well as Adam and the Patriarchs, and it remains the most important historical source on the Mongol Empire as a whole. As source material Rashid used all the available histories, but also, and more importantly, interviewed the merchants, mendicants, builders, and physicians fresh off the roads from China and India. They were seeking employment and sinecures; Rashid was seeking everything they could tell him. |

Inside, water splashed from fountains or was stored in unglazed urns. Everything that could be decorated, was. Brilliant colors were prized. The qa'da, or code of social behavior, that governed life in these homes was much the same in Baghdad as it was back in Ibn Battuta's Tangier, or virtually anywhere else in the Muslim world.

n Baghdad, Ibn Battuta determined to return to Makkah for his second Hajj, and again he took the Ion: way. The sultan himself invited Ibn Battuta to accompany his caravan northward, and Ibn Battuta accepted. His motive can only have been curiosity.

n Baghdad, Ibn Battuta determined to return to Makkah for his second Hajj, and again he took the Ion: way. The sultan himself invited Ibn Battuta to accompany his caravan northward, and Ibn Battuta accepted. His motive can only have been curiosity.

For 10 days he traveled with the mahalla, or camp, of Abu Sa'id. His description of the journey's routines is unusu ally detailed, perhaps because of the impression the journey made on him, or because, in retrospect, the practices of the Ilkhans were of particular interest to the Moroccan sultan under whose patronage he recollected his travels:

It is their custom to set out with the rising of the dawn and to encamp in the late forenoon. Their ceremonial is as follows: Each of the amirs comes up with his troops, his drums and his standards, and halts in a position that has been assigned to him, not a step further, either on the right wing or the left wing. When they have all taken up their positions and their ranks are set in perfect order, the king mounts, and the drums, trumpets and fifes are sounded for the departure. Each of the amirs advances, salutes the king, and returns to his place; then the chamberlains and the marshals move forward ahead of the king, ...followed by the musicians. These number about a hundred men... Ahead of the musicians there are 10 horsemen, with 10 drums.... On the sultan's right and left during his march are the great

amirs, who number about 50... Each amir has his own standards, drums and trumpets.... Then [come] the sultan's baggage and baggage-animals...and finally the rest of the army.

After parting from the mahalla, Ibn Batuta's itinerary took him, among other places, to the cities of Shiraz and Isfahan, and to Tabriz, which had become a major center of Islamic Mongol influence and power. In the latter city he regretted being able to remain only one night, "without having met any of the scholars," although his haste was due to the arrival of an order for his escort to rejoin Sultan Abu Sa'id's mahalla. At that time Ibn Battuta received his first audience with the sultan and a promise of provisions for his intended second Hajj.

All through the Rihla Ibn Battuta's personal character comes out in hints and fragments. Today he might be regarded as a bit of a fussbudget or a meddler, evidenced by the rather too generous outrage he expresses at minor lapses in others' behavior. In Basra, for example, he became so exasperated at grammatical errors in a Friday sermon that he complained to the local qadi, who commiserated. In Minya, Egypt he was livid that men at a public bath did not wear a towel around their waist. His complaint to local authorities resulted in a towel-rule being enforced "with the greatest severity." On the other hand, in the course of his travels he saw a great deal of blood spilled by royalty—as often as not, his patrons—without recording any scruples he may have felt. To us today this may seem a rather selective morality. We also know that he had few hesitations about fulsome flattery during audiences with potential benefactors. If Ibn Battuta was not quite a court poet, he was certainly one smooth jurist. Such was his character and his world.

Yet he was also capable of speaking truth to power at times, as his account of a meeting with the sultan in the Persian town of Idhaj reveals:

|

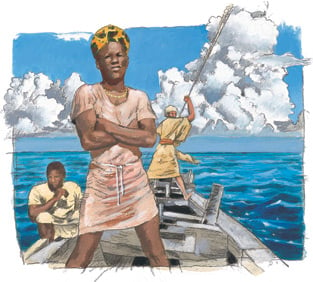

| Ibn Battuta described landing at Mogadishu, “a town of enormous size”: “When a vessel reaches the anchorage, the sambuqs, which are small boats, come out to it. In each sambuq there are a number of young men of the town, each one of whom brings a covered platter containing food, and presents it to one of the merchants on the ship saying, ‘This is my guest.’...The merchant, on disembarking, goes only to the house of his host.... The latter sells his goods for him and buys for him.... This practice is a profitable one for them.” |

I wished an audience with this sultan Afrasiyab, but that was not easily come by as he goes out only on Fridays, owing to his addiction to wine.... Some days later the sultan sent a messenger...to invite me to visit him. The sultan was sitting on a cushion, with two goblets in front of him which had been covered, one of gold and the other of silver....It became clear to me that he was under the influence of intoxication.... I said to him, "If you will listen to me, I say to you, 'You are the son of the sultan Atabeg Ahmad, who was noted for piety and self-restraint, and there is nothing to be laid against you, as a ruler, but this,'" and I pointed to the two goblets. He was overcome with confusion at what I said and sat silent. I wished to go but he bade me to sit down and said to me, "To meet with men like you is a mercy."

bn Battuta returned briefly to Baghdad, "received in full what the sultan had ordered for me," and used that gift not to go to Makkah—the caravan didn't leave for another two months—but rather to strike off again in another direction: the cities of the Tigris upstream from Baghdad. He returned to join the Hajj caravan, but he says little of this trip except that he caught an illness that from his descriptions may have been typhus. He made this Hajj in health so poor that "I had to carry out the ordinances seated."

bn Battuta returned briefly to Baghdad, "received in full what the sultan had ordered for me," and used that gift not to go to Makkah—the caravan didn't leave for another two months—but rather to strike off again in another direction: the cities of the Tigris upstream from Baghdad. He returned to join the Hajj caravan, but he says little of this trip except that he caught an illness that from his descriptions may have been typhus. He made this Hajj in health so poor that "I had to carry out the ordinances seated."

Ibn Battuta says he remained in Makkah two years on this occasion, but in fact his stay was closer to one year. His account is full of chronological confusions that madden the scholar, but are more tolerable when we remember that the Rihla was written not to record his every move with precision but to communicate knowledge of the things that the book's patron, the sultan of Morocco, would consider important. And in a rihla, if one were going to err in describing one's time in Makkah, one would err on the side of generosity, for "resident in Makkah" was an academic credential throughout Dar al-lslam rather as "studied at Oxford" is today—even absent any specifics of subject, duration or degree.

When Ibn Battuta set out again, it was southward. He certainly visited Yemen, which he called al-Mashrabiyah, "The Latticed Windows." Today, the byways of old Sana'a and Ta'izz still resemble his descriptions. The ornate latticeworks of carved wood admitted light and cooling breezes into Yemeni homes, but they blocked the inward view of passersby, preserving the residents' privacy. And, he wrote, "a strange thing about the rain in Yemen is that it only falls in the afternoon.... The whole town of Sana'a is paved, so when the rain falls it washes and cleans all the streets."

Inside those homes, walls were painted with as many colors as the owner could afford, and although there was little furniture, floors were covered with rugs to sit on. Men crossed their legs in front of them; women made cushions of their ankles as they folded their legs behind them. The last word in household luxury was a long diwan, a wide, low bench that might run all the way around the room, furnished with dozens of cushions. Beds were cushions that were rolled up and stuffed in a closet during the day.

Ibn Battuta's judgements were sometimes tart, as any traveler's might be on occasion:

| Omani markets were perhaps the most exotic in the 14th-century world, and Ibn Battuta devotes appropriately longer descriptions to them than others. Goods from Egypt, Arabia, Africa, India, and China all passed through Omani bazaars, and a partial list of products indicates just how cosmopolitan Muslim trade could be. There were pearls from the Maldives, medicines from Tibet, swords from Scythia, spices from the Andaman Islands, dye-wood from Africa, teak from Burma; Sindhi perfumes, Indian sesame, Persian pistachios, Mombasan ebony, Lankan ivory, iron, lead, gold, cotton, wool, leather and, in whatever space might have remained, fresh fruit. Today, an air-cargo manifest at Heathrow might hardly be so diverse. |

We proceeded to the city of Ta'izz, the capital of the king of Yemen. It is one of the finest and largest cities of Yemen. Its people are overbearing, insolent, and rude, as is generally the case in towns where kings have their seats.

Somewhat later he sums up a minor sultan named Dumur Khan as "a worthless person," and adds, "His town attracted a vast population of knaves. Like king, like people."

But he liked the country. He found Yemen's air fragrant with thyme, jasmine and lavender. Roses were picked while the dew was still on them; according to local folklore their fragrant attar, daubed on the body, all but guaranteed progeny. Myrrh, balsam and frankincense, whose export had helped build the already long-faded, ancient empire of South Arabia, were still produced.

Ibn Battuta then crossed the Red Sea to Somalia, disembarking first slightly north of Djibouti, then called Zeila. He judged it "a large city with a great bazaar, but it is in the dirtiest, most disagreeable, and most stinking town in the world" because of its inhabitants' habits of selling fish in the sun and butchering camels in the street.

He traveled down the East African coast as far as Mombasa and Kilwa, a region in which there were large numbers of Africans locally called Zanj; the name of today's Zanzibar keeps the word alive. They were "jet-black in color," he notes, with "tattoo-marks on their faces." In Kilwa, "all the buildings are of wood, and the houses are roofed with reeds." The local sultan, Abu al-Muzaffar Hasan, was "a man of great humility; he sits with poor brethren, and eats with them, and greatly respects men of religion and noble descent."

Then Ibn Battuta headed back to Arabia by way of Dofar, in southwestern Oman, where he mentions the ways the sultan lured merchants to his ports:

When a vessel arrives from India or elsewhere, the sultan's slaves go down to the shore, and come out to the ship in a sambuq carrying with them a complete set of robes for the oivner of the vessel [and his officers].... Three horses are brought for them, on which they mount with drums and trumpets playing before them from the seashore to the sultan's residence.... Hospitality is supplied to all who are in the vessel for three nights.... These people do this in order to gain the goodwill of the shipowners, and they are men of humility, good dispositions, virtue, and affection for strangers.

The traveler also described the custom of chewing betel nut, which is still socially important in many parts of the world today:

A gift of betel is for them a far greater matter and more indicative of esteem than the gift of silver and gold.... One takes areca nut, this is like a nutmeg but is broken up until it is reduced to small pellets, and one places these in his mouth and chews them. Then he takes the leaves of betel, puts a little chalk on them, and masticates them along with the betel nut.... They sweeten the breath, remove foul odors of the mouth [and] aid digestion....

Farther up the coast, Ibn Battuta describes the efficient way Omani fishermen used the sharks they caught. They cut and dried the meat in the sun, as dwellers on that coast still do, then dried the cartilaginous backbones further and used them as the framework of their houses, covering the frame with camel skins.

As for his own adventures, he describes a hired guide who, outside the city of Qalhat, turned robber. Ibn Battuta and his companion outsmarted the man by hiding in a gully and trekking into town, but with great difficulty: "My feet had become so swollen in my shoes that the blood was almost starting under the nails."

| The seasonal winds of the northeast monsoon facilitated Muslim trade far down the East African coast, and the southernmost extent of Ibn Battuta’s sailing was Kilwa, now a small coastal city in southeastern Tanzania. In 1329, however, it had recently become a very prosperous city with a local monopoly of the gold trade, and its merchant clans, which included the ruling family, lived in substantial houses, wore silk and jewelry, and ate from Chinese porcelain. Ibn Battuta found the sultan, Abu al-Muzaffar Hasan, to be pious and generous, and “a man of great humility; he sits with poor brethren, and eats with them, and greatly respects men of religion and noble descent.” |

rom this point, Ibn Battuta's itinerary again seems muddled, but it is known that in 1332 he returned to Makkah for his third Hajj. He doesn't say why, nor how long he stayed there. We do know that it was at about this time that he made his momentous decision to go to India. We also know that his motive was largely pecuniary. He had heard—perhaps in Oman, perhaps in Makkah or Baghdad, we don't know—that the Turco-Indian sultan of Delhi, Muhammad ibn Tughluq, was extraordinarily generous to Muslim scholars, and in fact had invited such people from throughout Dar al-Islam to come to his court.

rom this point, Ibn Battuta's itinerary again seems muddled, but it is known that in 1332 he returned to Makkah for his third Hajj. He doesn't say why, nor how long he stayed there. We do know that it was at about this time that he made his momentous decision to go to India. We also know that his motive was largely pecuniary. He had heard—perhaps in Oman, perhaps in Makkah or Baghdad, we don't know—that the Turco-Indian sultan of Delhi, Muhammad ibn Tughluq, was extraordinarily generous to Muslim scholars, and in fact had invited such people from throughout Dar al-Islam to come to his court.

That call, with its promise of royal generosity, was Ibn Battuta's lodestone for the next decade. He vowed to follow it. But as we might guess by now, his route to India was not the most direct. Indeed, it took him two years to get there.

One would think, looking at the map, that a goal-oriented traveler would go back to Oman, where he could embark on a dhow and ride the monsoon winds for about 40 days to the west coast of India. But at the time he made his decision to go, Ibn Battuta would have had to wait several months for the onset of the eastbound monsoon. Such was not his style.

Instead, he made his way back to Cairo, then around the east coast of the Mediterranean through Gaza and Hebron to a Genoese ship bound for Anatolia. Guided, it seems clear, by little more than serendipity and impulse, he crisscrossed that region, and became so familiar with its petty sultanates and local customs that his Rihla is our primary factual source for conditions in Turkey between the time of the Seljuqs and the arrival of the Ottomans.

One of these customs was the akhi, which is related both to the Turkish word for "generous" and the Arabic for "brother." The fraternal societies throughout the land that adopted the term clearly acknowledged both meanings. Ibn Battuta was introduced to them in a bazaar in Ladhiq (now Denizli):

As we passed through one of the bazaars, some men came down from their booths and seized the bridles of our horses. Then certain other men quarreled with them for doing so, and the altercation between them grew so hot that some of them drew knives. All this time we had no idea what they were saying [Ibn Battuta did not speak Turkish], and we began to be afraid of them, thinking that they were the [brigands] who infest the roads.... At length God sent us a man, a pilgrim, who knew Arabic, and I asked what they wanted of us. He replied that they belonged to the fityan...and that each party wanted us to lodge with them. We were amazed at their native generosity. Finally they came to an agreement to cast lots, and that we should lodge first with the group whose lot was drawn [and then with the other].

The akhis Ibn Battuta describes were known as fityans in Persia. They were a cross between a civic club and a trade fraternity, composed of unmarried younger men drawn by the ideals of hospitality and generosity that were such important virtues in the world of Islam. In Ibn Battuta's words, "They trace their affiliation...back to Caliph 'Ali, and the distinctive garment in their case is the trousers.... Nowhere in the world are there to be found any to compare with them in solicitude for strangers."

Such societies, however, were not unique to Anatolia. They existed in various forms and by several names throughout Dar al-Islam. Their social function was to institutionalize the sense of civic unity into a structure consistent with the ideals of the Qur'an but which was not addressed by the waqf, the hospice or other altruistic organization. Not hospitable only toward travelers, akhis and fityans also helped local individuals and their own members in time of need.

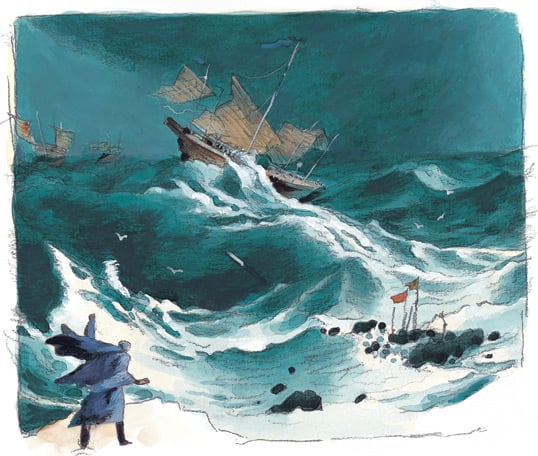

Leaving Anatolia, Ibn Battuta crossed the Black Sea to Crimea on a voyage one would think should have alienated him forever from sea travel. His vessel sailed into a storm so rough that at one point one of his companions went topside to see what was happening and returned to croak, "Commend your soul to God!" But God was merciful, and Ibn Battuta headed for the Mongol Kipchak Khanate, which rimmed the northern shore of the Black Sea.

There in Crimea Ibn Battuta bought a wagon for his travels. Unneeded and unknown in the lands of the camel, these were large, four-wheeled coaches drawn by oxen or horses. Ibn Battuta described them:

There is placed upon the wagon a kind of cupola made of wooden laths tied together with thin strips of hide; this is light to carry, and covered with felt or blanket-cloth, and in it there are grilled windows. The person who is inside the tent can see [other] persons without their seeing him, and he can employ himself in it as he likes, sleeping or eating or reading or writing.... Those of the wagons that carry the baggage, the provisions and the chests of eatables are covered with a sort of tent much as we have described, with a lock in it.... We saw a vast city on the move with its inhabitants, with mosques and bazaars in it, and the smoke of the kitchens rising in the air, for they cook while on the march.

| The Sultanate of Delhi, first established after 1206, was overthrown in 1320 by Khusraw Khan, a low-caste convert from Hinduism who apostasized and usurped the throne. Muslim control was reestablished by a Turco-Indian commander named Tughluq who restored economic and administrative stability But under the erratic rule of his son Muhammad, decay quickly became visible. When Ibn Battuta arrived in Delhi, the sultanate was governed by a ruling elite of Mamluk Turks perched atop layers of Hindu administrators, structured mainly along caste lines, atop legions of local functionaries who extracted taxes from the huge rural population. The system was corrupt throughout, and the result was revolts—22 of them during the reign of Muhammad ibn Tughluq. The imperial patronage that had lured Ibn Battuta to Delhi had, by the time he arrived there, degenerated to unpredictable alternations of generosity and brutality, and service to the sultan had become a risky, all-or-nothing business—as Ibn Battuta discovered. |

His descriptions of the long journey across the steppe reveal that his status as scholar, traveler and courtier was now such that he merited a new level of largesse from his hosts. By the time he crossed the Hindu Kush, he had accumulated a personal entourage of attendants, a sizable number of horses that he was prepared to give as gifts, and a number of wives and concubines. Thus had the lad from Tangier prospered—and greater good fortune was to come.

The trade routes Ibn Battuta traversed north of the Caspian were less busy than those across Afghanistan and Iran. Nonetheless, amber came down this way from the Baltic Sea to China via Moscow and the Volga. (He claims to have made an abortive attempt to journey up the Volga to the capital of the Bulgar state, but scholars doubt his veracity on this.) There is little doubt that he did indeed make a lengthy side trip to Christian Constantinople. He traveled there in the company of Princess Bayalun, the daughter of the Byzantine emperor Andronicus in who had been married, for political and economic reasons, to the Muslim Ozbeg, Khan of the Golden Horde, as his third wife; she was now returning to Constantinople for the birth of her child. Ibn Battuta reports that she wept "with pity and compassion" when he told her of his travels. Perhaps, unlike him, she was homesick.

After his return to the steppes from Constantinople, Ibn Battuta relates descriptions of the route's continuation along the Silk Road and its cities. Near Samarkand Ibn Battuta spent 54 days with Tarmashirin, the Chagatay khan who had only recently converted to Islam and was interested in what a worldly-wise qadi might tell him. Although Tarmashirin "never failed to attend the dawn and evening prayers with the congregation," he was overthrown by a nephew soon thereafter.

Ibn Battuta's exact path through Afghanistan and the Hindu Kush is uncertain because he does not make it clear where along the Indus he came out. But once on the hot plains, he headed for Multan, the sultan's westward customs outpost, which lay 40 days' march from Delhi "through continuously inhabited country." The traveler's pen waxed prolix as he noted the new foods, spices, trees, fruits and customs of this land where the ruling Muslims were the minority among the majority Hindu population.

![Recalling the court of Muhammad Özbeg Khan, one of the two Mongol sultans who, between them, controlled most of Central Asia, Ibn Battuta wrote: “His territories are vast.... He observes, in his [public] sittings, his journeys, and his affairs in general, a marvelous and magnificent ceremonial. It is his custom to sit every Friday, after prayers, in a pavilion, magnificently decorated, called the Gold Pavilion. It is constructed of wooden rods covered with plaques of gold, and in the center of it is a wooden couch covered with plaques of silver gilt.... The sultan sits on the throne...[and] afterward the great amirs come and their chairs are placed for them left and right.... Then the [rest of the] people are admitted to make their salute, in their degrees of precedence.”](images/part2/BATTUTA_12.47307.jpg) |

| Recalling the court of Muhammad Özbeg Khan, one of the two Mongol sultans who, between them, controlled most of Central Asia, Ibn Battuta wrote: “His territories are vast.... He observes, in his [public] sittings, his journeys, and his affairs in general, a marvelous and magnificent ceremonial. It is his custom to sit every Friday, after prayers, in a pavilion, magnificently decorated, called the Gold Pavilion. It is constructed of wooden rods covered with plaques of gold, and in the center of it is a wooden couch covered with plaques of silver gilt.... The sultan sits on the throne...[and] afterward the great amirs come and their chairs are placed for them left and right.... Then the [rest of the] people are admitted to make their salute, in their degrees of precedence.” |

bn Battuta's intention was to impress Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq sufficiently to win a sinecure—which we might justly call the Moroccan jurist-vagabond's first steady job. When he reached Multan he presented his credentials, including, in effect, the economic and social implications of his train and entourage, to the governor, who dispatched a courier to the sultan.

bn Battuta's intention was to impress Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq sufficiently to win a sinecure—which we might justly call the Moroccan jurist-vagabond's first steady job. When he reached Multan he presented his credentials, including, in effect, the economic and social implications of his train and entourage, to the governor, who dispatched a courier to the sultan.

It was very important to make a good first impression, for no one in Delhi was likely to know anything about the new arrival's background or lineage. When Ibn Battuta was finally told to proceed to court, he was also informed that it was the custom of the sultan to reward every gift with a much greater one. So Ibn Battuta struck a deal with a merchant who offered to advance him a sizable stake of dinars, camels, and goods in exchange for a fat cut of the proceeds when the sultan's reward was duly given. The merchant, clearly an early venture capitalist, also turned out to be a fair-weather friend, for he "made an enormous profit from me and became one of the principal merchants. I met him many years later at Aleppo after the infidels had robbed me of everything I possessed, but he gave me no assistance."

Ibn Battuta's long stays in Baghdad and Damascus, studying the law and discussing fiqh, or legal interpretation, with fellow jurists, served him well in Delhi. He impressed Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq, who appointed him qadi in Delhi with the handsome compensation of 12,000 silver dinars per year, plus a "signing bonus" of 12,000 dinars for agreeing to reside there permanently.

![“From [Kabul] we rode to Karmash, which is a fortress between two mountains, where the Afghans intercept travelers. During our passage of the defile we had an engagement with them.... We entered the great desert...[and] our company arrived safely (praise be to God Most High) at Banj Ab, which is the water of Sind [the Indus River].” Although Ibn Battuta’s descriptions of this leg of his journey are vivid, his geography is vague, and scholars still debate his route across the mountains to the Indus River Valley.](images/part2/BATTUTA_13.47307.jpg) |

“From [Kabul] we rode to Karmash, which is a fortress between two mountains, where the Afghans intercept travelers. During our passage of the defile we had an engagement with them.... We entered the great desert...[and] our company arrived safely (praise be to God Most High) at Banj Ab, which is the water of Sind [the Indus River].” Although Ibn Battuta’s descriptions of this leg of his journey are vivid, his geography is vague, and scholars still debate his route across the mountains to the Indus River Valley.

|

Ibn Tughluq's largesse, however, was out of proportion to the stability of his reign. His taxes beggared the countryside, yet in the cities his extravagance was mind-boggling. This was immediately apparent to Ibn Battuta, who observed:

This king is of all men the most addicted to the making of gifts and the shedding of blood. His gate is never without some poor man enriched or some living man executed.... For all that, he is of all men the most humble and the readiest to show equity and to acknowledge the right.... I know that some of the stories I shall tell on this subject will be unacceptable to the minds of many persons, and that they will regard them as quite impossible in the normal order of things.

Ibn Battuta devotes numerous pages to the lineage of the royal family, the history of the country, the details of a variety of elaborately choreographed court rituals, the wars and revolts preoccupying the sultan, his extensive gifts to religious and political men and his ceremonies entering and leaving the capital. On one particular triumphal return to Delhi, the sultan had arranged for an unusually spectacular procession of caparisoned elephants, infantry columns of thousands, musicians and dancers:

The space between the pavilions is carpeted with silk cloths, on which the Sultan's horse treads.... I saw three or four small catapults set up on elephants throwing dinars and dirhams among the people, and they would be scrambling to pick them up, from the moment he entered the city until he reached the palace.

Ibn Battuta soon discovered that he, too, could find himself on the wrong side of this mercurial ruler, whose character, if one can judge from the length at which Ibn Battuta wrote about him, fascinated—perhaps even transfixed—the jurist like that of no other ruler.

When the severe drought reigned over the lands of India and Sind...the sultan ordered that the whole population of Delhi should be given six months' supplies from the [royal] granary.... [Yet] in spite of all that we have related of his humility,...the sultan used to punish small faults and great, without respect of persons, whether men of learning or piety or noble descent. Every day there are brought to the audience-hall hundreds of people, chained, pinioned, and fettered, and those who are for execution are executed, those for torture are tortured, and those for beating, beaten.

There were administrative errors as well: Once Ibn Tughlug misconstrued Chinese texts about finance and decreed that, since silver was in short supply, coins should thenceforth be made of copper. Since those coins were backed by the sultan's gold and copper was abundant, counterfeiters had a field day, and the kingdom lost heavily.

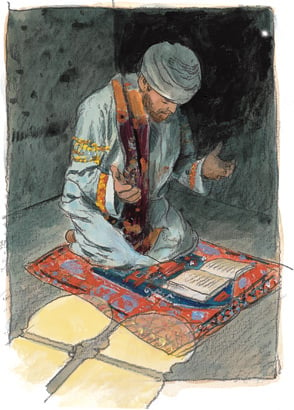

Eventually, Ibn Battuta was denounced at court for his association with a teacher whom Ibn Tughluq suspected to be a plotter. Disgraced and afraid for his life, Ibn Battuta retreated to study with a different teacher not in the ambit of the first. When Ibn Tughluq heard of this he commanded Ibn Battuta to present himself. "I entered his presence dressed as a mendicant, and he spoke to me with the greatest kindness and solicitude, desiring me to return to his service. But I refused and asked him for permission to travel to the Hijaz, which he granted."

![Ibn Battuta arrived in Delhi the year of his 30th birthday, and, though he fully expected to be given some position at the court of Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq, he was nonetheless taken aback by the high level of his appointment: “The sultan said to me, ‘Do not think that the office of qadi of Delhi is one of the minor functions; it is the highest of functions in our estimation.’ I said to him ‘Oh Master, I belong to the Maliki school [of Islamic jurisprudence] and these people are Hanafis, and I do not know the language.’ He replied, ‘I have appointed [two men] to be your substitutes; they will be guided by your advice and you will be the one who signs all the documents, for you are in the place of a son to us.’ The salary Ibn Battuta received for his services was enormous, and soon after his appointment he married into the royal family.](images/part2/BATTUTA_14.47307.jpg) |

Ibn Battuta arrived in Delhi the year of his 30th birthday, and, though he fully expected to be given some position at the court of Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq, he was nonetheless taken aback by the high level of his appointment: “The sultan said to me, ‘Do not think that the office of qadi of Delhi is one of the minor functions; it is the highest of functions in our estimation.’ I said to him ‘Oh Master, I belong to the Maliki school [of Islamic jurisprudence] and these people are Hanafis, and I do not know the language.’ He replied, ‘I have appointed [two men] to be your substitutes; they will be guided by your advice and you will be the one who signs all the documents, for you are in the place of a son to us.’ The salary Ibn Battuta received for his services was enormous, and soon after his appointment he married into the royal family.

|

After 40 days, Ibn Battuta recalled, Ibn Tughluq sent him "saddled horses, slave girls and boys, robes and a sum of money." This was clearly a summons. Again he presented himself to Ibn Tughluq, and he was no doubt thunderstruck to hear words he never forgot: "'I have expressly sent for you to go as my ambassador to the king of China, for I know your love of travel.'"

Here was an assignment Ibn Battuta could not even have dreamed of back in Makkah, when he first thought of heading eastward to seek his fortune. Now, it seemed that fortune lay spendidly before him.

t was an assignment for which Ibn Battuta was almost wholly unprepared by his study of shari'a law and his experience as a qadi. He was to accompany 15 Chinese envoys then in residence in Delhi and somehow oversee the transport and presentation to the king of China of a gift of "a hundred thoroughbred horses saddled and bridled; a hundred male slaves; a hundred Hindu singing-and dancing-girls"; some 1200 pieces of various kinds of cloth, each type of which Ibn Battuta details; "10 embroidered robes of honor from the Sultan's own wardrobe...; 10 embroidered quivers, one of them encrusted with pearls"; similarly decorated swords, scabbards, hats and, to top it all off, 15 eunuchs.

t was an assignment for which Ibn Battuta was almost wholly unprepared by his study of shari'a law and his experience as a qadi. He was to accompany 15 Chinese envoys then in residence in Delhi and somehow oversee the transport and presentation to the king of China of a gift of "a hundred thoroughbred horses saddled and bridled; a hundred male slaves; a hundred Hindu singing-and dancing-girls"; some 1200 pieces of various kinds of cloth, each type of which Ibn Battuta details; "10 embroidered robes of honor from the Sultan's own wardrobe...; 10 embroidered quivers, one of them encrusted with pearls"; similarly decorated swords, scabbards, hats and, to top it all off, 15 eunuchs.

On July 22,1342, with an escort of "a thousand horsemen," Ibn Battuta set forth for Calicut, where the plan was to put the embassy on one of the Chinese junks that were there waiting out the contrary monsoon.

The trouble that was to dog him for the next five years began immediately, during the long march from Delhi to the coast via Daulatabad, the sultan's second capital. Ibn Tugh-luq's rule was breaking down rapidly, and Hindu rebels now roamed the roads, sometimes as guerrilla armies, other times as brigands. Near the town of al-Jalali, the ambassador's retinue battled "about a thousand cavalry and 3000 foot [soldiers]." There were skirmishes over the next few days, and at one point Ibn Battuta became separated from his train and fell from his horse. He ran for his life—straight into the arms of one of the rebel bands. Their leader ordered Ibn Battuta executed, but for unknown reasons the rebels dithered and then let him go. He hid in a swamp, and for seven days found no refuge. The locals who saw him refused him food. A village sentry took away his shirt. He came to a well, tried to use one of his shoes as a bucket, and lost the shoe in the depths. As he was cutting the other in two to make sandals, a man happened along—a Muslim. He asked Ibn Battuta in Persian who he was, and Ibn Battuta replied warily, "A man astray." The man replied, "So am I." The Muslim then carried Ibn Battuta, fainting with exhaustion, to a Muslim village.

Thanks to his coreligionist, Ibn Battuta regained his caravan, and in time they reached Calicut. The gifts and the slaves were put aboard the hired Chinese junk while Ibn Battuta stayed ashore to attend prayers. There he decided that he was unwilling to travel on the junk because its cabin was "small and unsuitable." His personal retinue, including a concubine pregnant with his child, transferred to a smaller kakam that would sail with the junk.

In the night, a storm came up, which "is usual for this sea.... We spent the Friday night on the seashore, we unable to embark on the kakam and those on board unable to disembark and join us. I had nothing left but a carpet to spread out." But rather than abate the storm increased. Junks were cumbersome in shallow, narrow harbors, and the junk captain tried to make for deeper water where he might safely ride it out.

|

Ibn Battuta’s visit to a religious teacher who was later suspected of treasonous sentiments put him on the wrong side of the sultan, a ruler “most addicted to the making of gifts and the shedding of blood.” Imprisoned, Ibn Battuta “fasted five days on end, reciting the Qur’an cover to cover each day.” Though the sultan received him back and appointed him ambassador to China, the episode marked the end of the traveler’s hopes for a permanent sinecure in India, and the beginning of the most tumultuous years of his travels. |

This junk didn't make it. Ibn Battuta had the ghastly experience of watching it smash onto the rocks, where "all on board died." When the crew of the kakam saw what had happened, they did not return to pick up the ill-fated embassy's leader. Rather, "they spread their sails and went off,...leaving me alone on the beach."

Wrecked with the junk and lost with those aboard it was Ibn Battuta's Delhi career. He knew the first question Ibn Tughluq would put to him was why he had failed to go down with his ship. This time, no show of mendicancy would be an adequate answer.

Despite the trauma of the incident, Ibn Battuta inserts in his account one of those factual and informative observations that make his Ribla such a treasure today:

The [Sultan of Calicut's] police officers were beating the people to prevent them from plundering what the sea cast up. In all the lands of Malabar, except in this one land alone, it is the custom that whenever a ship is wrecked, all that is taken from it belongs to the treasury. At Calicut, however, it is retained by its owners, and for that reason Calicut has become a flourishing and much frequented city.

|

| “Now it is usual for this sea to become stormy every day in the late afternoon.... We spent the Friday night on the seashore.... That night the sea struck the junk which carried the sultan’s present, and all on board died.... When those on the kakam saw what had happened to the junk they spread their sails and went off, with all my goods and slave-boys and slave-girls on board, leaving me alone on the beach with but one slave whom I had freed. When he saw what had befallen me he deserted me, and I had nothing left with me at all except the 10 dinars that the yogi had given me, and the carpet.” |

Ibn Battuta withdrew to the port of Honavar, where he spent some six weeks in nearly solitary prayer and fasting—perhaps to keep a low profile, perhaps to grieve for the loss of his child and his dream of an exalted ambassadorial career, or perhaps to figure out what to do next. His retreat ended when he volunteered—exactly why he does not say—to lead the Honavar sultan's military expedition against the rival port of Sandapur. Though briefly victorious, the attack was swiftly countered: "The sultan's troops...abandoned us. We were... reduced to great straits. When the situation became serious, I left the town during the siege and returned to Calicut."

He had no means left to him, no prospects of an appointment, and one friend fewer in Honavar. There were few options.

Then fate beckoned again. He happened on a ship's captain bound for the remote Maldives.

|

Douglas Bullis is a researcher and writer who specializes in the Arab and Asian Muslim worlds. He divides his time between Southeast Asia and India, and can be reached at AtelierBks@aol.com or douglasbullis@hotmail.com. |

|

Norman MacDonald has illustrated more than 25 articles for Aramco World. He lives in Amsterdam, and became a grandfather while carrying out the present assignment. |