Written by Sheldon Chad

Photographed by Michael Nelson

ohamed Salem’s head turns under his black howli turban to follow the lone car passing on this dirt road 150 kilometers (93 mi) outside Ouadane in the Mauritanian Sahara. We’re shooting the breeze about the weather.

ohamed Salem’s head turns under his black howli turban to follow the lone car passing on this dirt road 150 kilometers (93 mi) outside Ouadane in the Mauritanian Sahara. We’re shooting the breeze about the weather.

“When the rainy season comes around, I get the feeling that I should turn on the radio and expect a balagh, like, ‘Mohamed Salem: It rained in Zuarat. Go. It will be good for the camels.’”

Any balagh (message) he receives comes to him over the radio program Al-Balaghat (“the messages,” pronounced “ahl bah-la-ghaat”), broadcast nationwide in Mauritania each weeknight for the past 42 years. You’d be hard-pressed to find a Mauritanian alive who hasn’t heard it, and most know it intimately. When Al-Balaghat first hit the airwaves shortly after Mauritania’s independence from France in 1960, the population of the sand-swept country was much as it had been for centuries: more than 95 percent nomadic. How, then, its founding fathers asked, to get diverse peoples to see themselves as a nation?

The answer began to take shape in 1966, when the nation’s young Radio Mauritanie started the nightly broadcast of personal messages. Sparely worded like telegrams in simple Arabic, honey-dipped in the regional Hassaniyya dialect, they were delivered in a rapid-fire, hypnotically resonant, rhythmic plainsong that quickly became an art form all its own. It was as if the traditions of desert griots (troubadors), who had helped centuries of nomads exchange songs, stories, poems and gossip, had stepped into the age of mass media.

The answer began to take shape in 1966, when the nation’s young Radio Mauritanie started the nightly broadcast of personal messages. Sparely worded like telegrams in simple Arabic, honey-dipped in the regional Hassaniyya dialect, they were delivered in a rapid-fire, hypnotically resonant, rhythmic plainsong that quickly became an art form all its own. It was as if the traditions of desert griots (troubadors), who had helped centuries of nomads exchange songs, stories, poems and gossip, had stepped into the age of mass media.

An instant hit, the broadcasts riveted everyone to a receiver every night, on the chance that they’d hear a message for themselves or about someone they knew. If not, it was still good food for the imagination, for Mauritanians have a unique conversational habit of stopping just short of finishing certain sentences, with the result that listeners have to pour in a little of themselves to catch the meaning—or even create it. With the genius of Al-Balaghat, the new nation began to be forged over the airwaves. And five nights a week, you can still hear it.

Mohamed Salem says it takes him 10 to 15 days to cover the few hundred kilometers to Zuarat’s greener pastures. Dressed in his traditional sweeping boubou, he may look as though he’s living in a desert pastoral much as his ancestors did, but then he upends your assumptions. He relies on the radio, he says, “because if you’re in a place like this, you don’t have cell phone coverage. You have to listen to Al-Balaghat.” Like Mauritania itself, where even in remote areas everybody seems to juggle two or more cell phones and wide-screen televisions can be found in nomads’ tents, he seems to stand with equal firmness in the 14th, 20th and 21st centuries.

In Nouakchott, the situation can be much the same. One-third of the national population of three million has migrated into the Mauritanian capital over the last 30 years, and the constant winds drift sand everywhere. You can be a welcome guest in a home right out of Paris’s seventh arrondissement, and then a goat wanders in the door; you can step outside and realize that later in the evening, the hosts will repair to their real living quarters—the khaimas, or tents, set up in the courtyard.

When Mauritania was carved out of French West Africa, the prospective capital was a small fishing town. It seems ironic, then, that today, with the exception of a still-modest fishing wharf and a deepwater port, the capital’s Atlantic beachfront is surreally desolate for kilometers inland. The distance is ostensibly a buffer against flooding, but it also seems to suit the disposition of a country whose face is turned firmly toward its deserts.

“Al-Balaghat wa al-itissalat al-shaabiya,” says Mohamed ould Agatt. “That’s the real name of the show. It means ‘The People’s Messages and Communications.’”

The historic program’s “first family” is splayed out around a typically Mauritanian living room. Despite low sofas around the room’s perimeter, everyone seems to prefer the carpets in the middle. Famously strong green tea circulates every couple of minutes. It’s the home of Mohamed ould Agatt’s father, the late Mohamed Lemine ould Agatt, founder of Al-Balaghat. (Ould means “son of,” equivalent to the English suffix -son in “Williamson.”)

Ould Agatt, as everybody calls Mohamed Lemine, was a giant of a man—both physically and influentially, they say—who cast his long shadow on Mauritanian culture from his perch at Radio Mauritanie. Born in the southeast, he had a classical Mauritanian education in Islamic studies, Arabic grammar and poetry before becoming a successful merchant in Nigeria and, later, the national station’s first announcer.

“My father said to the [first] president, Mokhtar ould Daddah, ‘There are no telephones, no telexes. There is nothing. Only this show can compensate,’” says Mohamed ould Agatt. The president warned him, he continues, that the post and telegraph offices would resent the competition, and they would sue him. “My father replied, ‘Tell them that the show won’t be broadcast during the day. That way it won’t interfere with the post office!’” He smiles broadly.

Touttout, Ould Agatt’s widow, chimes in, declaring, “He was a creator!”

Mohamed continues, explaining that Al-Balaghat became popular “because it rendered a service to the people.” Before that, “the content of the radio programs wasn’t what the people were interested in. But Al-Balaghat was useful. If you were going to receive money, Al-Balaghat told you. If your son was coming, Al-Balaghat told you—” Touttout interrupts again, asserting that her son was missing the point: “Most people listened to it because they liked his sweet voice! It was like music.”

On the wall in the studios of Radio Mauritanie, there is a sign that declares: La Radio c’est avant tout la créativité. (“Above all, radio is creativity.”) Moustapha Lefnane, program director for the station, believes this is a key to understanding Al-Balaghat.

“There is no ‘dream dimension’ to a cellular phone,” he asserts. “But the imaginary side of the balagh is actually a culture. [For example,] you wait for your father, who has been away for three years in France. Then you hear on the radio that he is coming back in a week. Then everybody gets ready and will be waiting for him 15 kilometers from the village, and we bring out the camel that he is going to ride. This dimension of the imaginary side, almost spiritual side, of the message reinforces human relations. Compare this to the immediacy of communication by cell phone, or by Internet, which makes people lose the imaginary aspect, the spiritual aspect of communication.”

The gatehouse next to Radio Mauritanie’s parking lot has been the home of Al-Balaghat since the early days. Over its cement threshold two generations of Mauritanians have stepped to send their balaghat.

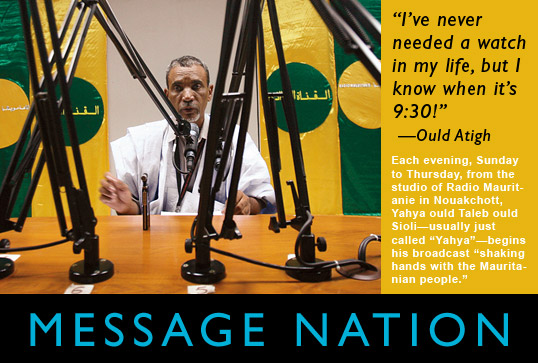

Inside, Yahya ould Taleb ould Sioli, the current presenter of Al-Balaghat, is trimly bearded and dressed in a western sports jacket. He is all dignity and appreciation. There is also Abdou ould Brahifal, the friendly cashier. Yahya, as everyone calls him, is busy with a customer. He listens and composes the message in a scribble of ink on paper. He never has to edit, he says: After 25 years, he knows the forms that will satisfy the customer and, at the same time, hit a harmonic chord that resonates in the Mauritanian soul. When he’s finished, he reads the message back to the customer, who gives his assent and then moves over to Ould Brahifal to pay the 300 ouguiya fee (about $1.30) and get his receipt. “It is like a beautician’s shop,” says the cashier. “You have to be gentle with the customer. It’s very personal, very human.”

This particular client, Yahya explains, bought two condolence messages, “one from him and one from his friend from the same family, for the same deceased.” Yahya displays them. “The vocabulary is the same. The same here and the same here. If he has his own style, I will do it [that way], but generally everyone just gives me the names and who he wants to send it to and where. All the phrases are known,” he says. “Customers know the form completely. They want it rendered exactly. It’s not just style. There is an incredible tradition.”

In the same way that Mauritanians, among themselves, often leave sentences for their listeners to complete, the balaghat also carry an unexpressed aspect of the message. Like compressed paper tablets that, dropped into water, expand and blossom into flowers, the messages reveal their full complexity only when soaked in the water of their listeners’ imagination; simple, dry words can thus convey the wellsprings of emotion, not only for the addressee but for the listening nation. Somehow, Ould Agatt found the right combination of phrasing, musicality and rhythm that unlocked emotion for a desert people whose culture demands self-control and restraint.

Yahya, who is not sure whether he is 49 or 50 years old, exhibits no pride when he admits that, “yes, every Mauritanian knows my name,” and that he, along with his predecessor Al-Balaghat presenters, is among the best known, best loved people in the country.

He says that, when he came to the job in 1983, “they said I wouldn’t last because it’s too difficult. And I want to tell you, it isn’t easy. There are very difficult words. There were words that I couldn’t say, that didn’t exist in Arabic or Hassaniyya, that took me 17 years to learn. How to do it? Difficult! Ould Agatt was very intelligent. He was the one who invented the balagh,” marvels Yahya.

Yahya reads about 20 to 30 balaghat each weeknight, from Sunday to Thursday, and about two-thirds are condolences—except at the end of the school year, when there is a flood of congratulatory messages for graduates and their families. Sometimes, he adds, there are also announcements from the police concerning lost and found objects, animals, even people. All balaghat he receives are read the same day, even if their numbers cut into subsequent programming.

Mohamed Lemine “Eddeda” Salleck, one of the most famous radio personalities in Mauritania since the 1970’s, tips his hat to Yahya’s talents in rendering Al-Balaghat as both a utilitarian personal service and a national cultural institution somewhere between poetry, music, oratory and prayer.

“Look: I am a journalist, a Hassaniyya poet and a cultural critic of Mauritanian society. I know music better than the griots, and yet I cannot successfully read Al-Balaghat,” Eddeda singsongs with an ensorcelling grin.

“Radio was what connected Mauritanians, taught us that there was a state, that there was a president, and there were ministers, and there was a parliament. There were shows with singers, and we took time to sit and listen to the music, but when Al-Balaghat came on, it was more important. The other world was for leisure, but this was some-thing that could change your life. Everybody knew Post Office Box 200 was for Al-Balaghat.”

The desert oasis of Tergit, 450 kilometers (280 mi) northeast of Nouakchott, is surrounded by monumental mountains that fall down into valleys. Date palms frame the sky at every angle behind thatched huts. Out behind the descending pools of water, in a gully framed by majestic sand dunes, you’ll find shepherd Hatari Ahmed, with a disposition as sweet as a date. He’s with his camels, waiting for tourists when he’s not shepherding them and his goats and camels between Tergit and Chinguetti.

Most nights, you’ll find him in an encampment of six families, each huddled around its own radio, with Yahya’s incantatory voice seemingly coming from all directions. Asked when the last time was that he himself received a balagh, Ahmed answers, “Last week. My mother died in Nouakchott.” She had been sick, he explains, when he last saw her, eight months past. “I was listening: She was not expected to live long.” As is proper, he sent a balagh of condolence of his own. “It’s the only way to communicate with family all over the country,” he says.

Ahmed doesn’t know who went to the Al-Balaghat office to send the original announcement, but it doesn’t matter. “Everybody sends everybody balaghat all the time.”

The beginnings of Radio Mauritanie itself go back to the Réseau France Outre-Mer, the French Overseas Network, which in the 1950’s broadcast to the conjoined future countries of Senegal and Mauritania from a tight little modernist building by the Senegal River.

Mohamed Mahmoud Weddady, who started as an announcer at Radio Mauritanie in 1959, the year before Mauritanian independence, recalls that from Nouakchott, he used a one-kilowatt medium-wave transmitter that had been left in the country by Americans after World War ii. Its signal was relayed—barely—to Senegal. “It covered the desert,” says Weddady with a pause and a grin, “of Nouakchott.”

At the time the future capital had only 3000 people.

After independence, Mokhtar ould Daddah, the first president, wanted to establish Radio Mauritanie as “the voice of the nation,” says Weddady.

Naha Saidi, Mauritania’s first female radio and television journalist, picks up the history. Ould Agatt, she says, was a colleague of Weddady’s who gained fame as a political critic, lampooning Mauritania’s Moroccan rivals on the air. “He would use the nuances of the Arabic language to make them look ridiculous,” says Saidi. So sharp was his tongue that the Moroccans demanded he be silenced. Mauritania had no choice but to bend to the will of its more powerful neighbor. Ould Agatt was transferred to local broadcasts for three years. When he came back in 1966, Weddady was his boss, and together they brought Al-Balaghat to the air.

Ahmed ould Hamza, the governor of Nouakchott, calls the program “a culture. The culture of the Arab Bedouin is nomadic. It’s the culture of the message. It’s text-messaging for the Bedouin.”

Another 320 kilometers (200 mi) beyond Tergit, on the edge of the sandy wilderness of the Adrar Sahara’s Erg Ourane, the once-great caravan city of Ouadane is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Climbing through the ruins that tumble down the mountainside, Med El Moktar, aged 75 or 76, is barefoot and wearing a bright blue boubou, his white goatee coming to a point. He is, he says, a teacher and former shopkeeper in Abijan, Côte d’Ivoire—and an astute world-radio listener.

“I listen to all radio stations—Canada, United States, China. I know the history of the us, Canada, Britain and Germany. I know that from the radio.”

For him, Al-Balaghat is an international courier for balaghs to his son in Côte d’Ivoire, who listens on shortwave. He says he also received a balagh all the way from France, sent by a scholar who had visited him while writing a book on Islamic sciences. But he didn’t respond. (“I didn’t speak French. I didn’t know her address, so I let it go.”)

Farther away still, in Montreal, Canada, eight expatriate Mauritanians get together for dinner. As they might in Nouakchott, they plant themselves on the carpet around a platter of lamb. You half expect a goat to scurry in here, too. One of them abstains from eating: He’s “present” via an Internet chat connection from Calgary. As they talk, reminiscences about Al-Balaghat come with ease.

“I love to listen to that show,” says restaurateur Ould Atigh. “It makes me sleepy right away. Nine-thirty, milk the goats, pour some of the milk on laîche [a sticky tart] and start eating. Listen to Al-Balaghat, and by the time you finish, you sleep. Then in the daytime, I’d try to remember the balaghat. I’d remember the presenter had so many balaghat he couldn’t breathe. I’d sit and start remembering and repeating the balaghat that happened yesterday, but I’d change them to my village. I would take the balagh and make it so it’s this guy who gets married, that woman who dies,” he says. “I’d imagine that one sent a bag of sugar. This one, the old man got credit and had to pay it back—things like that. Sitting there and making balaghat just like the old man from the night before. I’m telling you, I’ve never needed a watch in my life, but I know when it’s 9:30!”

Back in Yahya’s wood-paneled sound studio at Radio Mauritanie, with its computer and its control room, it’s evening, almost airtime—8:30 p.m. nowadays.

“I have developed an attitude,” he says. “I am happy, very happy, to do this. But after 25 years I’ve become habituated. I’m compelled to do this. I’m obligated to do my job. It’s a simple thing.”

He’s sure that in 50 years, in 100 years, there will still be Al-Balaghat—c’est pour tout le temps—for always.

He positions the microphone, and he starts in on Al-Balaghat. There are no historic tapes of Ould Agatt, Mustapha Bouna or Ahmed ould Tfiel—the other announcers who preceded him—but it is hard to imagine a sweeter voice than Yahya’s.

Anyway, as Yahya says, for Al-Balaghat, it’s all really the same voice.

Yahya opens with his customary salutations to his listeners and then slides into the show. It’s exactly as he says: Yahya is “shaking hands with the Mauritanian people.”

“Salaam alaykum. (Peace upon you.) This is now the time for the communiqués.”

His droning intonation carries the reverence of prayer, but at the speed of an auctioneer. Listening, somehow you feel that it is not just him, but Ould Agatt, Mustapha Bouna, Ould Tfiel too, all in that studio. In the historic continuity of the desert, he is the modern griot of the radio dial.

Atar, Chinguetti, Ouadane, Kaédi: He goes through the towns, one by one, missing neither a step nor a beat. At the end, it’s “goodbye, until tomorrow.” Message sent.

Message Translations

Al-Balaghat is broadcast in simple Arabic for Hassaniyya and Arabic speakers, and Radio Mauritanie soon recreated the program in the nation’s three other principal language groups: Wolof, Pulaar and Soninke. Called the local equivalent of communiqué in each language, these counterpart programs are broadcast during the noon hour in the ascending order of each minority’s population: At 12:05 it’s in Wolof, at 12:20 it’s in Soninke, and at 12:40 it’s in Pulaar.

“People are listening in the whole country,” says 30-year-veteran Pulaar presenter Amadou Ba, who, at 79, is the senior announcer at Radio Mauritanie.

For these shows, the presenters don’t work at the Al-Balaghat office, so they don’t have the same contact with the customers. They’re handed the communiqués to read, but there can still be deep emotional attachment. Tall and impassioned, Moussa Dirbira has broadcast in Soninke for 11 years.

Especially with death notices and condolences, Dirbira says, the communiqués have a special place in his community.

“You have to do the communiqué,” he says. When he lost his own uncle, he explains, “I spent 110,000 ouguiya, 250 euros [$470] to rent a car. A lot of money. I spent two weeks in the village. We put him in the ground, and now that I’m back, my mother says, ‘You still have to make a balagh, because if you don’t, it’s as if you didn’t do anything.’ It’s sacred with us.”

It will go on, he says, and even with cell phones and satellite television, he thinks people are more attracted than ever to the communiqué style.

“Even though they have more ways to communicate, it doesn’t matter. It has to be broadcast on the radio. When it’s noon and the communiqués are broadcast, for 20 minutes everybody’s focused. Even the flies don’t move.”

|

Sheldon Chad (shelchad@gmail.com) is an award-winning screenwriter and journalist for print and radio. Residing in Montreal, he travels extensively throughout the Middle East and West Africa. |

|

Michael Nelson (masrmike@gmail.com) is the Middle East regional photo manager for the European Pressphoto Agency (EOA) in Cairo. |