I say there are different ways of looking at the world, and most of them are not from a 25-meter height, like that pompous obelisk in Rome. To hear him tell it, nothing matters but the high and mighty. Well, I never met a pharaoh or a king; I never had armies of slaves and such setting me up or knocking me down. I never went to the Circus and had a clown like Nero race around me in his chariot. So what? I may not look like much, but I did something a lot more important. Hear me out if you want to know how a scrap of everyday trash got rescued from a garbage heap to change the course of human history.

Pardon my language, but I come from what Greek folks call hoi polloi—the common people, the working class, the lower crust. I don’t know much about anything high, whether it’s society, class, brow, fashion or falutin’. It’s another world up there, a place for emperors and obelisks, but not for me. I like it down here where little things make big differences. A pot means as much to the poor as pillars and palaces mean to some Caesar who thinks he’s a god. From my beginning to my end, I always kept close to the ground. I am a humble son of earth and water, a foster child of fire.  Born in the potters’ quarter of Athens—still called Kerameikos (“Ceramicsville”) today—I grew up hard and fast. Only hours out of the kiln, I stood on a rough-hewn shelf, my mouth wide open in awe of my surroundings. Swearing craftsmen of every description were spinning their pots and their yarns. I listened to their colorful shoptalk and watched as their muddy fingers taught the clay to become fancy things with frilly names that I struggled to pronounce: the shapely loutrophoros for ritual bathing, the slender lekythos for storing oil, the deep krater for mixing water and wine, the big-handled kantharos for serious drinking and the pitcher-like oinochoe, with a spout for pouring. Talented painters turned many of these pots—excuse me, vases—into the masterpieces you see in books and museums today. Not me. I never got glazed or painted. Even the old redneck crocks had more class than me. Since nobody bothered to make me beautiful, I knew right away what to expect. I’d never earn an ode from some famous poet, or make it into a museum. No, I was the workaday ware of every kitchen and storeroom in bustling Athens, the kind bought, used and broken in bulk, mourned for a moment—but only because of what I spilled—then immediately forgotten and replaced. All too soon, I joined the sweepings of some poor man’s house, a vessel wrecked on a sandy floor.

Born in the potters’ quarter of Athens—still called Kerameikos (“Ceramicsville”) today—I grew up hard and fast. Only hours out of the kiln, I stood on a rough-hewn shelf, my mouth wide open in awe of my surroundings. Swearing craftsmen of every description were spinning their pots and their yarns. I listened to their colorful shoptalk and watched as their muddy fingers taught the clay to become fancy things with frilly names that I struggled to pronounce: the shapely loutrophoros for ritual bathing, the slender lekythos for storing oil, the deep krater for mixing water and wine, the big-handled kantharos for serious drinking and the pitcher-like oinochoe, with a spout for pouring. Talented painters turned many of these pots—excuse me, vases—into the masterpieces you see in books and museums today. Not me. I never got glazed or painted. Even the old redneck crocks had more class than me. Since nobody bothered to make me beautiful, I knew right away what to expect. I’d never earn an ode from some famous poet, or make it into a museum. No, I was the workaday ware of every kitchen and storeroom in bustling Athens, the kind bought, used and broken in bulk, mourned for a moment—but only because of what I spilled—then immediately forgotten and replaced. All too soon, I joined the sweepings of some poor man’s house, a vessel wrecked on a sandy floor.

Castoffs like me had no cause to hope for second chances. was Humpty Dumpty, you might say, without the fuss of all the king’s horses and men. Shattered, I waited in the household trash for that last journey out to the bottom of some deep, dark well or a smelly garbage pile beyond the city. Until then, I had nothing to do but pass my final days in idle trash-talk with other scraps of pottery. Some bits bragged of vases they had spotted in this fine shop or that; others put on airs about the jobs they had once had—say, preparing food for a wedding feast or funeral. Most of us, however, fantasized about one last chore before the grave. We wanted to become something called an ostracon, a piece of busted pot you could write on with something sharp. This was all the rage back then.

Sure, massive stone pillars may seem like the ultimate memo pad, but you need a swarm of stonecutters just to jot down a note or two. Not very practical for most people. That’s why your daily life leaves a paper trail, not a desk drawer full of obelisks. Back in my day, even paper (in the form of imported papyrus) could be too pricey for the average Greek. In Athens, a grocery list would have cost more than the groceries! For simple folk, some other cheap, available item had to serve for the lists and tallies of everyday living. That explains why Athenians sometimes fumbled through their trash to find shards of shattered crockery like me. On us, a Greek could scratch a useful line or two, just as you might do today on the back of an old envelope.

But I didn’t start this squabble with an obelisk just to brag about becoming a shopping list. Give a fellow more credit than that! Talk about dreams coming true: Scratched on me were three and a half words—not much, you think, right? But you can thank me later, because those words saved what you folks now call Western Civilization. Think I’m joking? Let me finish my story.

You see, the Athenian house where I lived belonged to a citizen. That made the man somebody special, even though you couldn’t pick him out in a crowd of slaves or foreign workers. All the poor pretty much dressed and talked alike. In fact, the rich often complained that in the streets of Athens you couldn’t tell a free man from a slave, making it hard to know who you could shove out of your way without breaking the law. My owner didn’t care a lot about appearances (maybe that’s why he bought me in the first place), but he sure was proud to be a registered citizen with the right to vote. He had no education, yet he attended the peoples’ ecclesia—the assembly—whenever he could. There he voted on everything having to do with how the government was run. Imagine that: a commoner in charge of war, strategy, finances, religion—you name it. He even helped make all the laws! His politics (they called it this because he lived in a Greek polis, or city-state) depended on what he heard in the great public debates, and on the gossipy news that constantly bounced around the agora, or marketplace. It seemed to me that he lived an exciting life where the people (not including women, foreigners or slaves) decided everything for themselves. He called it a democracy.

I remember moving into this man’s trash at a very scary time—not just for me, but for the whole city. Day after day my owner came home from the ecclesia and agora with terrifying talk of a Persian invasion. Persia, I learned, was the biggest power on Earth. Its empire stretched from the edges of Greece all the way to the other side of the world where only monsters lived. The Persians were unbelievably rich, powerful and angry—at Athens in particular. They accused us of meddling in their empire, which was true enough, but my owner said it couldn’t be helped on account of our duty to spread democracy. Only eight years earlier, the Athenians had beaten off a large military force sent by Persia’s King Darius to punish the city. The decisive battle, fought at Marathon, was already the stuff of legend: The soldiers who won it were considered heroes, our greatest generation. But everybody knew the Persians would try again. Year after year the tension grew, until finally, in what you folks call 482 BC, we went on red alert. Darius’s son Xerxes, Persia’s new “king of kings,” made no secret that he intended to destroy Athens once and for all.

I remember moving into this man’s trash at a very scary time—not just for me, but for the whole city. Day after day my owner came home from the ecclesia and agora with terrifying talk of a Persian invasion. Persia, I learned, was the biggest power on Earth. Its empire stretched from the edges of Greece all the way to the other side of the world where only monsters lived. The Persians were unbelievably rich, powerful and angry—at Athens in particular. They accused us of meddling in their empire, which was true enough, but my owner said it couldn’t be helped on account of our duty to spread democracy. Only eight years earlier, the Athenians had beaten off a large military force sent by Persia’s King Darius to punish the city. The decisive battle, fought at Marathon, was already the stuff of legend: The soldiers who won it were considered heroes, our greatest generation. But everybody knew the Persians would try again. Year after year the tension grew, until finally, in what you folks call 482 BC, we went on red alert. Darius’s son Xerxes, Persia’s new “king of kings,” made no secret that he intended to destroy Athens once and for all.

But the news was not all bad. From my place in the jumble of cracked pottery heaped in the kitchen trash, I overheard my owner one day crowing like a rooster that he was suddenly rich. Apparently, state miners, digging on public land, had discovered a bonanza of pure silver. The find was worth a fortune. Word on the street was that every citizen should expect to receive an equal cut of the proceeds. And why not? What poor Athenian would want this silver tucked away in the state treasury instead of his very own pocket? “Easy come, easy keep,” my excited owner agreed.

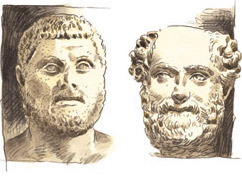

So did a famous politician named Aristeides, one of the heroes of Marathon and a leader so honest and wise that the people called him “Aristeides the Just.” This fine man proposed that the city should parcel out fair shares of the silver to every citizen just as soon as the miners (all of them state slaves) could be lashed into action.

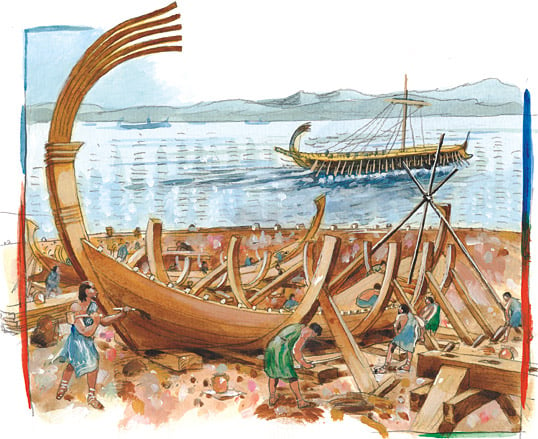

But of course, this was democratic Athens, where even a no-brainer had to be debated. For days my owner fretted around the city, worried that some fool in the ecclesia or agora would come up with some different scheme for the money. And sure enough, somebody did. The man was named Themistocles—although some called him more colorful names. This guy had the nerve to propose that, instead of keeping the money, the people should let him spend it on a bunch of warships. You know how expensive those things are? You should have heard my owner howl at such an idea! Boats? No navy saved Athens last time at Marathon. That was our boys in the infantry. And didn’t we already have a bigger fleet than most any other city-state anyway? And if Athens really did need more ships for some reason, didn’t our laws say that the wealthiest Athenians had to cover these expenses through special taxes? What kind of leader picks the pockets of the poor to spare the rich?

Obviously, most citizens made fun of Themistocles, but the man simply would not shut up. Crowds showed up at his speeches just to boo him, but all they got was an earful back. Themistocles went on and on about the many dangers faced by our seaside city, starting with the powerful island of Aegina, visible just offshore, to that armada of Xerxes’s massing farther to the east. Listening to him, you’d think the sky was falling as he warned that the future of Athens depended on its navy, not on the desire of every shortsighted buffoon to buy a bunch of brand new pots with a pocketful of silver. As you can imagine, the debate got pretty heated.

At first, my owner hung all the arguments of Themistocles on a familiar hook: “Pure politics, nothing more.” After all, Themistocles had never in his life missed an opportunity to oppose anything Aristeides stood for, so why should this distribution of silver be any different? Whatever one said, the other could not say the opposite fast enough. They hated each other so much that Athens, folks sighed, wasn’t big enough for both of them. They attacked each other in the courts and turned the ecclesia into a continual battleground. Many citizens naturally dismissed Themistocles’s witless proposal as no more than a sad outgrowth of this tiresome feud. The man of my house assured us all that the costly fleet proposed by Themistocles had only one mission: to sink the ambitions of his rival Aristeides.

When you’re waiting out your last days in a trash pile, you follow a drama like this very closely, just hoping to be around long enough to see how it finally ends. I thought I had this one all figured out, but, boy, was I wrong. You see, one afternoon my owner came home not so sure about the witlessness of Themistocles’s idea. Some people, even the poor ones like my owner, were starting to change their minds. Day by day they found it more difficult to ignore Themistocles, who sounded less and less preposterous, while Aristeides started to seem more like a cheap panderer. What if it was true after all that Athens could not defend itself with the ships it already had? How could even the rich possibly cough up enough money to build hundreds more right away? Look at the big picture, my owner finally said. Face up to the patriotic duty of every good man to put aside self-interest and give up his share of the mining revenues for military defense. Yes, here with me lived an uneducated man who could nonetheless actually think for himself, and not just about himself. Somehow, in all the fire and smoke of Athenian politics, this commoner had settled on the notion of the greater good at the expense of personal gain. He wanted a free country more than free cash. I never felt prouder to be in his house.

I was not there for long. A showdown came between the new supporters of Themistocles and the remaining followers of Aristeides. Something had to be done fast, so all of us broken pots got together, and we decided the fate of the silver, the city and, as it turns out, of Western Civilization, too.

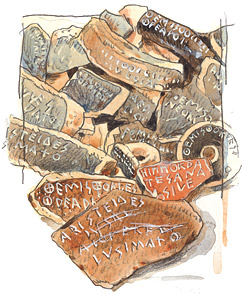

It happened when my owner fished me from the garbage and used me to write down his vote in a special kind of election named (in my honor) an ostracism. This was an election you wouldn’t want to win, because if you did, you were given 10 days to get lost. Every year, the Athenians could do this. In the winter, they met in the ecclesia and voted whether to ostracize anyone or not. If they decided to go ahead with it, they got together in the spring to choose a “winner.” On that occasion, every registered citizen (like my owner) showed up at the agora with a piece of pottery. There, each voter scratched onto his ostracon the name of any one person he wanted gone, and then he pitched this ballot into a pile to be counted. If at least 6000 people voted, then the guy who got his name written down the most had to leave Athens for a decade. The person ostracized did not lose his property or his citizenship. This wasn’t exile—more like a decade-long time-out. After that he could return to the city and pick up where he left off, no hard feelings.

Okay, folks, I know this sounds pretty much like mob justice. Nobody’s name was off limits, and the fellow ostracized had no right to defend himself or appeal. But, truthfully, don’t you wish you could occasionally vote to send someone away—a president, senator, judge, teacher, talk-show host, movie star, noisy neighbor, nosy relative…? Your choice, your reasons. The Athenians knew the system could be abused (and I hear it later was), but they felt a lot safer if they could defend their new democracy against dangerous individuals. An annoying neighbor was not going to rack up enough votes to get ostracized, but a guy who tried to take over the city just might get the boot. Good riddance, I say. Or some stubborn leader who refused to compromise might have to leave. Good riddance to him, too. That’s exactly what I went to the agora to do—to tell either Themistocles or Aristeides that, sure enough, Athens was not big enough for both of them. I left it up to my owner to decide which name I would carry into the voting box, and then to my grave.

As you can imagine, there was a lot of poli- ticking going on at the last minute. Supporters of both sides worked the crowd, and I worried that my owner might suddenly change his mind again. He was clearly nervous, too, because he cradled me to my grave with trembling hands: He could barely read or write. Trying to hide this fact, he did his best to scratch the right letters on his ballot. All crooked but correct, he etched along my upper edge the letters A-R-I-S-T-E-I-D-E-S. This first part he managed okay, probably because he practiced it from the very day he decided to support the naval proposal of Themistocles. But then his memory failed. What should have come next was the name of Aristeides’s father, Lysimachus, to make sure people knew exactly who he meant. My owner sweated through the first four letters and quit. Completely stumped, he gave up on that word and tried something else—the name of the district in Athens where Aristeides’s family was from, Alopekethen. He worked at this for a while, ending up with A-L-O-P-E-K-E-E-I. Sensing a problem, he tried to change the last E to something different but never could decide how to fix it. He needed help.

As you can imagine, there was a lot of poli- ticking going on at the last minute. Supporters of both sides worked the crowd, and I worried that my owner might suddenly change his mind again. He was clearly nervous, too, because he cradled me to my grave with trembling hands: He could barely read or write. Trying to hide this fact, he did his best to scratch the right letters on his ballot. All crooked but correct, he etched along my upper edge the letters A-R-I-S-T-E-I-D-E-S. This first part he managed okay, probably because he practiced it from the very day he decided to support the naval proposal of Themistocles. But then his memory failed. What should have come next was the name of Aristeides’s father, Lysimachus, to make sure people knew exactly who he meant. My owner sweated through the first four letters and quit. Completely stumped, he gave up on that word and tried something else—the name of the district in Athens where Aristeides’s family was from, Alopekethen. He worked at this for a while, ending up with A-L-O-P-E-K-E-E-I. Sensing a problem, he tried to change the last E to something different but never could decide how to fix it. He needed help.

My owner did not struggle alone, of course. Plenty of hoi polloi found it hard, if not impossible, to write down even a simple thing like a name. That doesn’t make them dumb, just uneducated, and nobody should look down on them for it. I’m proud to say that Aristeides didn’t, even though in the end he got enough of their votes to “win” the ostracism. Fact is, he even helped one illiterate citizen write out a vote against him! The story goes that the poor voter didn’t recognize Aristeides when he asked him how to spell the name. Aristeides showed the guy without letting on who he was, then out of curiosity asked why he disliked Aristeides so much. “Never met him,” admitted the voter, “but I’m sick and tired of people calling him ‘The Just’ all the time.”

Something similar happened to my owner and me. I don’t know who it was (surely not Aristeides again), but a fellow voter helped straighten us out. He looked at what had been done to me and shook his head. He grabbed me and roughly crossed out everything but the first word, Aristeides. Then, smooth and sure, he scratched down the father’s name, Lysimachus, straight across my lower edge, and walked away.

I was done, tattooed with the three and a half words that tell the story of my incredible life. With a proud man’s determination and a stranger’s help, I made a difference. I counted in the historic vote that ostracized Aristeides the Just. This broke the deadlock over the silver. Themistocles got to stick around and supervise the building of the fleet, and those very warships really did save Athens and its democ- racy a few years later, defeating the invading armada of Xerxes. Otherwise, Western Civilization as you know it would never have existed. Without little old me, even that gigantic obelisk in Rome wouldn’t be the same. Help his highness do the math: No cheap pot, no pottery scrap; no scrap, no ostracon; no ostracon, no ostracism; no ostracism, no money for ships; no ships, no victory; no victory, no Athens; no Athens—well, no telling what sort of “Modern Ones” he’d be talking to.

Of course, I missed seeing most of the good I did. After I got rid of Aristeides, government workers buried me and a bunch of other ballots near the agora. Some of us had voted for Aristeides or Themistocles, and some for various other fellows. We had no idea, at the time, about the great sea battle, or that years later Themistocles would be ostracized, too. No, we didn’t see daylight again for 2500 years. Archeologists finally dug us up and recognized right away who we were. I got a special new name: P5976. I got my picture put in books, and, by golly—talk about luck!—I ended up in a museum (the Agora Museum) after all. If only my swanky-vase cousins could see me now, the grubby poor kid from the Kerameikos who changed the world.

|

Frank L. Holt (fholt@uh.edu) is a professor of history at the University of Houston and most recently author of Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005) and Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003), both published by the University of California Press. |

|

Norman MacDonald (www.macdonaldart.net) is a Canadian free-lance artist, living in Amsterdam, who specializes in history and portraiture. He painted salukis in Saudi Aramco World’s May/June 2008 issue; these are his first portraits of potsherds. |