Written By Frank L. Holt

the obelisk of Seti I

and of his son Ramses II, was born and raised a devoted Egyptian in spite of my current address. At birth, I weighed more than 250 tons, and I measured more than 24 meters’ (78') in length. It took an army of chanting men with chisels and heavy hammers to labor me out of the granite quarries near Elephantine. Workers swarmed over me for months, midwives on a mission, as the parent rock was cut away, and I was delivered, cut by cut, blow by blow. Great levers then lifted me to an embankment, where thousands pulled at straining ropes, dragging me, gently despite my great bulk, to the Nile. There, cradled in a special barge and the focus of a mobile ceremony, I journeyed down through history, from Thebes and Abydos to Memphis and Anu.

the obelisk of Seti I

and of his son Ramses II, was born and raised a devoted Egyptian in spite of my current address. At birth, I weighed more than 250 tons, and I measured more than 24 meters’ (78') in length. It took an army of chanting men with chisels and heavy hammers to labor me out of the granite quarries near Elephantine. Workers swarmed over me for months, midwives on a mission, as the parent rock was cut away, and I was delivered, cut by cut, blow by blow. Great levers then lifted me to an embankment, where thousands pulled at straining ropes, dragging me, gently despite my great bulk, to the Nile. There, cradled in a special barge and the focus of a mobile ceremony, I journeyed down through history, from Thebes and Abydos to Memphis and Anu.

My noisy procession came ashore

at Holy Anu, City of the Sun. Seti I, beloved of Ptah, conceived me as a monumental shaft of the sun’s pure light that would stand before the temple of Ra. Before Pharaoh’s wish was accomplished, however, fate intervened: Suddenly (as we Egyptians say), old Seti became Osiris, ruler no longer of the living, but the dead.

I lay heartbroken and half-born until Seti’s son, the long-lived Ramses II, took his place as Lord of the Two Lands, Upper and Lower Egypt—in 1279 BC, as I think you would say. Like a second father, Ramses set me towering over the sun-priests at Anu. In the hush that fell as I found my footing, everything finally made sense to me. At last I saw the world as it was intended to be—not that and near,

but far below, stretching out in

every direction with vistas of beauty and mystery. I marveled at the tiny upturned faces of the followers of

Ra. I recognized nearby my brother obelisks, some already a thousand years older than I, arrayed across the city like a scattering family of tourists. Across the Nile, I glimpsed the pyramids that alone made me feel small among the monuments of men. What a wonderland in which to be raised! Holy Anu, now the suburbs of Matariya and ‘Ain Shams in Cairo

—a city I have never seen, by the way—bustled back then as a center

of worship and learning. Anu’s fame attracted visitors from foreign lands, and they marveled at me. On my polished sides, the priests pointed out the deep-cut symbols that expressed the pride and piety of my two fathers,

Seti and Ramses. The Greeks, who came here often, gave to these signs the popular name hieroglyphs, which translates into your language as “priestly carvings.” They also coined

a playful word for my siblings and me

—obeliskos, meaning “a little souvlaki skewer.” How envy makes men jest!

I lay heartbroken and half-born until Seti’s son, the long-lived Ramses II, took his place as Lord of the Two Lands, Upper and Lower Egypt—in 1279 BC, as I think you would say. Like a second father, Ramses set me towering over the sun-priests at Anu. In the hush that fell as I found my footing, everything finally made sense to me. At last I saw the world as it was intended to be—not that and near,

but far below, stretching out in

every direction with vistas of beauty and mystery. I marveled at the tiny upturned faces of the followers of

Ra. I recognized nearby my brother obelisks, some already a thousand years older than I, arrayed across the city like a scattering family of tourists. Across the Nile, I glimpsed the pyramids that alone made me feel small among the monuments of men. What a wonderland in which to be raised! Holy Anu, now the suburbs of Matariya and ‘Ain Shams in Cairo

—a city I have never seen, by the way—bustled back then as a center

of worship and learning. Anu’s fame attracted visitors from foreign lands, and they marveled at me. On my polished sides, the priests pointed out the deep-cut symbols that expressed the pride and piety of my two fathers,

Seti and Ramses. The Greeks, who came here often, gave to these signs the popular name hieroglyphs, which translates into your language as “priestly carvings.” They also coined

a playful word for my siblings and me

—obeliskos, meaning “a little souvlaki skewer.” How envy makes men jest!

|

| YANN ARTHUS-BERTRAND / CORBIS |

| Four times my weight and almost

twice my height, the largest obelisk ever quarried in Egypt lies stillborn at Aswan, fatally cracked. |

With tireless determination, great Ramses built and bred and smote until he, too, became Osiris. He left behind scores of human sons, as well as stone monuments of eternal fame like me, and his legacy of imperial grandeur. I never admired a pharaoh more than Ramses, nor loved one more than Seti. When Egyptians looked up at me, I know they were really looking up to them.

Neither of my two fathers could have foreseen the troubles that awaited me. When I was only about 630 years old, the Assyrians descended on Holy Anu. When I was 775, the Persians followed. I watched in horror the day that King Cambyses of Persia made my home a ruin. The temples of Anu burned, and the priests perished. Some of my sibling obelisks toppled to the ground, where they lay like sunbeams lost in shadow and dust, extinguished and massively frail. On their behalf I did all I could to uphold light and life in a city darkened by defeat.

Only 200 years later, a young

Greek from Macedonia avenged us. Alexander overthrew the Persian Empire and liberated Egypt. I glimpsed the extraordinary lad myself when he marched through Anu, a city now called “Heliopolis” in his language, “Sun City.” He knew the place from Homer, his favorite poet, whose Odyssey described how the souls of the dead passed by me on their way

to the Underworld. It did not take long for Alexander to follow them

on the same sad journey, and he was buried nearby in the magnificent city that still bears his name: Alexandria. The young man’s ambitious general Ptolemy soon became our pharaoh, and his dynasty endured until one

of the worst days of my life, for when the last of the Ptolemies departed from Egypt, so did I.

|

| CARLITOS GUILLERMO LUNGHI / EGIPTO.COM |

| A Roman ship, above, carried me off like so many others from Anu (Heliopolis), where but one survivor remains, below, now surrounded by a suburb of Cairo. |

|

| LUIGI MAYER (1802) |

Her name was Cleopatra, and she was goddess and queen. Her blood was Greek, but the heart that pumped it was surely Egyptian. She loved this land, knew its history, spoke its language and ruled its people as Ramses might have done—if not, that is, for Rome. That little Latin-speaking nation far to the west had grown powerful. As its legions gobbled up most of the Mediterranean world, we grew certain that Egypt would be next. Cleopatra did all she could to spare

us the worst. Her charm and cunning captivated Caesar, but senatorial assassins struck him down. She tried again with Antony, but he was little help when Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian, rallied the Egyptophobic Romans against them both. Antony committed suicide, as did Cleopatra—or so Octavian claimed. I was almost 1300 years old on the day the Romans added Egypt to their empire. In my still-young life I had withstood many such conquests, each one traumatic, but none so personally humbling as the victory of Octavian over Cleopatra. If stone could weep, I would have flooded the Nile.

Only a few priests remained in Heliopolis to keep alive the rites of Ra and to lead the Romans on guided tours among the ruins. I watched as these priests, each too eager to please, catered to the conquerors. “Just over there,” they would say,

“is where Plato stayed for

13 years while he studied Egyptian astronomy. Over here dwelled Potipherah’s daughter, who married the Hebrew Joseph to please Pharaoh. Moses lived here, too, and set up some of

these obelisks.”

In the wide eyes of the Romans, I saw avarice as they stared up at me, calculating my height, my weight and my age as they would a prospective slave. And so it was that

I became known to Octavian himself, who never met a monument he did not wish to make a servant of his regime. Initially, he wanted to carry off another obelisk, the largest one at Karnak, up the Nile, but that one proved too massive to move. Instead, I was chosen as the first of Egypt’s many obelisks to be hauled away to Rome, that so-called “Eternal City” that was younger than me by centuries. Once again I was laid flat, and the river waters bore my weight to the Mediterranean, whence I sailed up the tiny Tiber as a trophy of war. I

am a captive still to this day.

|

| AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY |

| I was commemorated by Trajan on this medal. |

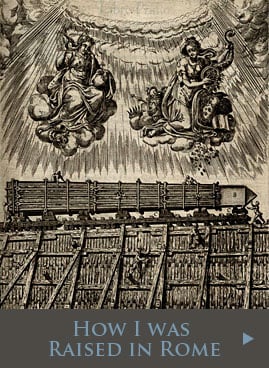

One of the worst things the Romans ever did, they at least did well. Taking me down, transporting me across the

sea and setting me up again was a remarkable feat of engineering. By the time it was done, Octavian had taken the new name Augustus, and he had established himself as the first emperor of Rome. He had me hauled to the Circus Maximus, where I was raised on the infield of the racecourse. There, I bestowed fame on the emperor as I

once had the pharaohs. The Romans could not read my hieroglyphs, but they busied themselves between races by mouthing the words inscribed in Latin on two sides of my base. Augustus listed there his numerous titles followed by the obvious boast: “Having brought Egypt under the dominion of the Roman people, I dedicated this gift to the Sun.” Since the Circus Maximus was itself originally designed for solar worship, I was indeed a fitting adornment. My popularity was such that I set a trend that eventually brought many of my brother obelisks to Rome: There are now more of us here than in any other city in the world. Only one still stands in Heliopolis,

a lonely sentinel of Ra, while a few more live

solitary lives in a kind

of obeliskoid diaspora in places like Paris, London, Istanbul and New York.

But as one accustomed to priestly solemnity and courtly ceremony, my new home bewildered me. Around me fidgeted up to 150,000 toga-clad fanatics screaming for entertainments. They cheered for the team-colored chariots revolving around me lap by lap, the speeds at each straightaway building hopes for spectacular crashes at the turns. They clamored at horse races, boxing competitions, wrestling matches and holiday spectacles. When they craved blood, their rulers obliged with beast hunts and grim-faced gladiators. Yes, I saw all of it, for the now-famous Colosseum was not yet built when I arrived in Rome, and its arena could fit a dozen times inside

the Circus Maximus. It seemed as if the tons of sand and dust around me never settled unless dampened by sweat and gore.

I peered down on the slaughter of men, bears, elephants, lions, hippopotami and even crocodiles when

once Augustus turned the Circus into

a swampy replica of an Egyptian

landscape in which men hunted the uncaged beasts. For that moment

I felt at home again, and I silently roared with the delighted crowd

when a toothy croc made lunch of

a careless Roman, although I had

different reasons for my amusement.

During Nero’s reign, I witnessed a far different spectacle—a conflagration of unprecedented scale. The catastrophe began here in the Circus Maximus, and it spread quickly through the adjoining shops and far beyond. For six days, roaring flames and acrid smoke cast shadows across my face, giving a ghostly aura to the perishing city. I survived the great fire, but many temples, parks and tenements did not. Within days, the Romans

eased their suffering by returning to

the Circus, where Nero himself raced a chariot—to cheer them up, he said. He considered himself quite the champion, even though no competitor could safely prove how deluded the man really was. Some years later, he laid at my feet all of the prizes he had won, numbering in the thousands, and not one of them legitimate. When Nero died—still deluded—just a few months afterward, the dynasty of Augustus expired with him.

Nero had yearned to be not only

an athlete, but a singing sensation. Ironically, it was I who became what you might call Rome’s greatest rock star. People came from every province of the empire to admire me. Soon, no monument matched my fame—not even the pyramids I had envied so much in my youth. Roman coins

circulated far and wide with my image stamped upon them. Special medallions, called contorniates, pictured the Circus, chariots careening around its racecourse, with me at the center. There I was, a scion of Seti and Ramses, personifying the majesty of Rome! If images of the Eiffel Tower

or the Washington Monument ever appear 1500 years from now on the currency of some alien civilization, you will have some idea of how important I, the Egyptian, had become to Rome. Still, I would never have willingly traded my home in Holy Anu for all the adulation I received in Rome.

|

| GASPAR VAN WITTEL / CHRISTIE’S IMAGES / CORBIS |

| For the last half millennium, Piazza del Popolo has been my home. In the early 18th century, a Dutchman painted my portrait, showing behind me the Via Corso that leads to the old forum and the Circus Maximus. |

Imperial dynasties pass like days

in the long life of an obelisk. When I approached the age of 1860 years, however, something remarkable occurred in the Circus Maximus. Constantine II, a member of one of ancient Rome’s last ruling families, brought to me a distinguished visitor from my fatherland. Older and taller than I, the obelisk

of Thutmose III and of his grandson, Thutmose IV, joined me on the spina of the Roman Circus. My brother had stood unscathed at Karnak for 18 centuries, the very obelisk that Octavian had originally coveted but was unable to move. Finally, an emperor named Constantine the Great pulled him down and floated his bulk as far as Alexandria, where he intended to make this grandest of obelisks a souvenir for the city of Constantinople, “the new Rome.” When death interrupted that plan, the emperor’s grandson dragged my brother obelisk to my side. On these matters we commiserated a great deal amid the tumult of the arena, my brother sharing news of recent centuries in Egypt while I educated him about the habits and history of Rome.

Almost imperceptibly during our conversations, the world around us veered in new directions. The empire that had stolen us weakened, stumbled, and fell. Soon one of us, too,

fell, when some evil men attacked my brother and toppled him into the now-idle arena. Alone among the ruins, I thought again of Holy Anu and could not bear the sorrow. On a day I no longer remember, I too reeled and thundered onto the ground. Earth and grass slowly smothered me, until the warmth of Ra was gone. Ashamed

and shivering, shattered in three pieces, I could only dream of Egypt.

|

| GUENTER ROSSENBACH / ZEFA / CORBIS |

| Today, I am dizzied by all the motorized chariots but cheered by the people who gaze up at me and—I believe it is

a new gesture of respect—raise a little box to their eye, wink at me, and pass on. |

Nothing disturbed my dreams and solitude until I was nearly 2800 years old. Gardens had grown over me, tended by the clergy of a religion I did not recognize. Learned antiquaries knew, however, that I had once towered nearby, and some of them used long iron probes to search for me. Their success occasioned a solemn visit from Pope Sixtus V, who—like the emperors of old—thought me a suitable monument for yet one more “modern state.” My pieces were strapped onto heavy sledges and pulled through the streets of Rome until we reached the place they called the Piazza del Popolo, the “Plaza of

the People.” To make way for my new home in the center of the square, one of ancient Rome’s own monuments—the Septizodium—was destroyed and its fragments used to build for me a strong foundation. Workmen chiseled away part of my lower shaft to create a

stable foothold so that, healed, I could stand up once more. Yet another Latin inscription commemorated my life,

the Papal text complaining of the

former abuses done to me: “Pope

SIXTUS V ordered that this pitiable ruin, broken and fallen, should be exhumed, restored, moved and dedicated to the Invincible Cross: 1589.”

I was exorcised, purified and capped by a cross and the pontiff’s insignia.

I do not wear these strange clothes comfortably, but… “when in Rome….”

And so it is that for the last half millennium this Roman piazza has been my home. Here, I overlook an ancient gateway into the city associated with the Flaminian Way, and hence

I am often referred to now as “the Flaminian Obelisk.” For a while,

I served as a starting post for horse races, as well as the setting for public executions—both disturbing reminders of my days in the Circus Maximus. Worse, though, have been the motorized chariots racing around me for

no prizes whatever except a parking space. I cannot imagine what Nero might have done with them.

I, the obelisk of Seti I and his son Ramses II, have risen and fallen like the pendulum of history itself. Up I swung at Holy Anu when my fathers ruled

all the lands. Down I pivoted and up again when the Romans took over the world. When their empire fell, I tilted, too. When the Middle Ages passed, I swept upright again to announce the dawn of Europe’s Renaissance. Now

I wait tirelessly for the next downbeat, for surely I must signal someday another age yet unimagined.

|

Frank L. Holt ([email protected]) is a professor of history at the University of Houston and most recently author of Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005) and Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003), both published by the University of California Press. |