Written by Sheldon Chad

Photographed by Michael Nelson

|

|

|

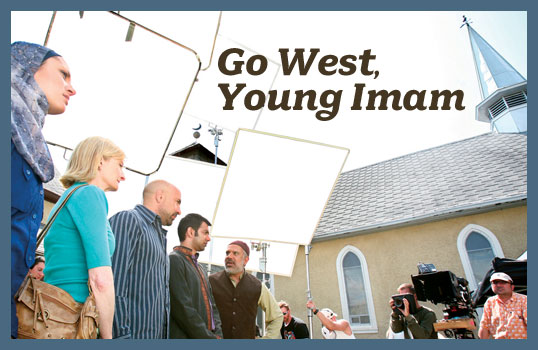

| Top: The prairies that stretch in all directions from Regina, capital of Saskatchewan, make a setting for “good-natured and good-hearted humor,” says producer Michael Snook, middle. “Even when making fun of each other, [the characters] obviously care about each other.” Bottom: Director Michael Kennedy confers on the set with actors Zaib Shaikh, Sitara Hewitt and Carlo Rota. |

e’re outside the Mercy Mosque, which holds its weekly prayers in space rented from a church in a slightly tattered but otherwise nondescript neighborhood in a small town in western Canada. As the worshipers exit, greeting each other and shaking hands with the imam, one of them snipes, “Well, well, a good sermon—for once!” The imam shoots back, “Yes, I noticed a lot less twitching from your part of the room.” The next voice says, “Cut!” and a crew of gaffers turns the awning-like diffusion screens around to get ready for the next scene.

e’re outside the Mercy Mosque, which holds its weekly prayers in space rented from a church in a slightly tattered but otherwise nondescript neighborhood in a small town in western Canada. As the worshipers exit, greeting each other and shaking hands with the imam, one of them snipes, “Well, well, a good sermon—for once!” The imam shoots back, “Yes, I noticed a lot less twitching from your part of the room.” The next voice says, “Cut!” and a crew of gaffers turns the awning-like diffusion screens around to get ready for the next scene.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) television sitcom Little Mosque on the Prairie will air its second season this fall.

When the show premiered with eight episodes last winter, more than two million viewers tuned in—good numbers for Canada. So did The New York Times, CNN, the BBC and other world media, all of whom found newsworthy a show that depicted the daily life of Canadian Muslims as, well, normal —and worth joking about.

Mary Darling, the show’s executive producer, says CBC scooped up the concept from the first line of creator Zarqa Nawaz’s “pitch”: She simply walked in wearing her head-scarf and said, “I think it would be great to do a comedy about my community.” Darling reflects, “It was the timing. The fact we are doing a Muslim comedy, humanizing a population that otherwise has not been humanized, is not a bad thing at all.”

Nawaz’s ideas come out rat-a-tat. “You write what you know. What I knew was growing up in Toronto, and then being transplanted to a small town and going to a small mosque—one imam, a very small community—dealing with my community and dealing with the outer community as a whole, and how 9/11 affected my relation-ships with everyone.”

She offers, “They always say that Muslims are this foreign ‘other’ that ‘we Canadians’ can’t relate to—yet when people watch this show, they say, ‘This could be me, this could be my wife, these could be my kids—even though I’m not Muslim.’”

Anton Leo, head of comedy development for CBC, recalls Nawaz’s pitch, too, which she made at a network office in her hometown of Regina, capital of the prairie province of Saskatchewan. He recalls her anecdote about moving to Regina: “When they started unpacking, a neighbor called the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police] because there was this group of Muslims taking boxes out of a cube van. I thought that was a great story.”

The success of Nawaz’s pitch earned her three years of slogging through script after script, honing characters and story ideas to get the “eureka!” moments that make or break a television series. As a documentary filmmaker, Nawaz, 39, was new to comedy writing, so CBC teamed her up with two polished writers.

|

| Little Mosque on the Prairie is “a sitcom and not political satire,” says Zarqa Nawaz, the show’s creator, who was born in Liverpool, England and raised in Toronto. In 1994 she moved to Regina with her husband and four children. A former radio journalist and documentary filmmaker, she wants “people to laugh with Muslims like they would laugh with anyone else, and feel comfortable doing so.” |

hrough the fictional town of Mercy, Nawaz uses the show to explore what she calls the “dynamics of the mosque,” with its “motley crew” that she says is “based on archetypes in the real world.” In a switchabout, the visible minority in Little Mosque is the non-Muslim majority population of Mercy.

hrough the fictional town of Mercy, Nawaz uses the show to explore what she calls the “dynamics of the mosque,” with its “motley crew” that she says is “based on archetypes in the real world.” In a switchabout, the visible minority in Little Mosque is the non-Muslim majority population of Mercy.

“There’s the orthodox Muslim immigrant [Baber] who feels he’s right and everybody else is wrong. The secular Muslim [Yasir] is trying to balance religion and secular life so his business doesn’t get affected,” says Nawaz. And, of course, there’s a character cut in Nawaz’s own image: Rayyan, “who is always agitating for change.”

As for Amaar, the handsome young Canadian-born imam who is also central to the cast, Nawaz wrote him in because she “wanted to shake things up.” Amaar, she says, “cares very much about his faith, but he’s also of the same culture as Canada.” In real mosques in Canada, where most imams are foreign-born, it’s rare to see one like Amaar, she admits. But she wonders, “What would happen if you brought Amaar into a small-town, conservative Muslim congregation? He would be forced to deal with the women, who would expect him to side with them, yet be diplomatic because the conservative, immigrant men are still an important part of the congregation as well. So how would his life be?”

Nawaz says that the show is, in fact, a story of Canada. “I wasn’t conscious of it, but I think Canada has been very successful in its multicultural model, especially in assimilating the Muslim community, in a way no other country in the world has been.”

Numbers bear out her case: Earlier this year, a survey found that 95 percent of Canadian Muslims said they were proud to be Canadian, and when asked whether Muslim immigrants to Canada should adopt “Canadian values,” 75 percent agreed. Jack Jedwab, the executive director of the Association of Canadian Studies, explains that, in his experience, “the ‘us versus them’ phenomenon isn’t obvious in Canada…. The message of multiculturalism is that there is no contradiction between being Muslim and being Canadian.”

But—on television?

|

| Aliza Vellani, 15, plays Layla Siddiqui, daughter of Baber, “the Archie Bunker character.” Layla, says Vellani, is “very energetic,” and “cunning around her dad,” whose conservative home Layla sarcastically calls “Baberistan.” Personally, Vellani says,“I don’t have the same character. I’m not quite as rebellious.” |

Leo says that the network ran focus groups to solicit feedback from a variety of Muslims in Toronto. “After all the laughing, and all the recognizing themselves, there was a really heated debate about whether the show should go on. Some said yes, and others weren’t sure whether it was good for the culture.” It was decided, Leo says, when one man asked, “‘Brothers, brothers, what do we want? Do we want to be seen in movies blowing up buildings as terrorists?

Or do we want to be seen as fathers and sons and people with families, with a sense of humor?’ And they all went, ‘Right, right, right….’”

oronto, home of CBC’s headquarters, is also where the interior scenes for this fall’s 20-episode season are being filmed over the summer. Among the metro area’s 4.7 million people are some 80 ethnicities and 100 languages, and Toronto receives half of the country’s annual 325,000 immigrants. The city contains about one quarter of the national Muslim population, second only to Montreal.

oronto, home of CBC’s headquarters, is also where the interior scenes for this fall’s 20-episode season are being filmed over the summer. Among the metro area’s 4.7 million people are some 80 ethnicities and 100 languages, and Toronto receives half of the country’s annual 325,000 immigrants. The city contains about one quarter of the national Muslim population, second only to Montreal.

|

| Hewitt and Shaikh work on the set. Filming this year’s 20-episode series took four months in Toronto and two months in Regina. |

You have to travel 2700 kilometers (1675 mi) west from Toronto to Nawaz’s hometown of Regina to see the sets for the show’s exterior scenes. You’re now on the prairies of Saskatchewan, where license plates proclaim “the land of living skies.” With an area greater than Germany and the UK combined but a population of less than one million, Regina can seem very far from Canada’s multicultural center of gravity.

But not, it seems, when it comes to Islam: It was still another 800 kilometers (500 mi) farther west on these prairies, in Edmonton, Alberta, where in 1938 the sons and daughters of Muslim farmers and fur traders built the first mosque in North America: the Al Rashid Mosque. That was the original “little mosque on the prairie.”

|

| On the set, a makeup assistant stands ready. |

Saskatchewan’s first Muslim immigrants arrived at the end of the 19th century, but in 2001 in Regina, there were only 770 Muslims recorded in a population of fewer than 200,000 people. Today, the Muslim community itself estimates that recent immigrants may have pushed the number up to between 1500 and 2000. Their real-life imam is Hafez Ilyas Sibyot, director of the Islamic Association of Saskatchewan. With a wraparound beard, white kufi skullcap, long, loose shirt and trousers and a PDA (“I’m a simple person, so I carry a small Palm”), he enters the prayer hall of the mosque Nawaz regularly attends. “This is where the Little Mosque on the Prairie is,” he says, adding that, like its fictional counterpart, the building was bought from a church. He points to a necessary adaptation: the slanted lines on the purple carpet that orient worshipers toward Makkah.

Across town, playing Imam Sibyot’s fictional counterpart, Amaar, is actor Zaib Shaikh, who has just finished shooting a scene in which he admonishes his congregants for lying, gossiping and arguing during the holy month of Ramadan. With his dark eyes and hip demeanor, Shaikh could be a teen-magazine heartthrob in half the countries of the globe. Born in Toronto to Pakistani immigrant parents, Shaikh learned the Qur’an and the rituals of Islam as a child, but he says it was not until he was in his 30’s that he “started focusing on my religion and taking it more seriously. How does it apply to me and what I’ve learnt, and now how does it apply holistically to what I believe in? It coincided with the casting of the show and was complementary to the process—a great happy circumstance.”

Others of the actors also feel a natural affinity for their roles—even those who are not Muslim. Sitara Hewitt, of Pakistani and Welsh background, could share those teen magazine covers with Shaikh.

|

| Hafez Ilyas Sibyot is director of the Islamic Association of Saskatchewan—“the real little mosque on the prairie,” he says—which Nawaz and her family attend regularly. Like the fictional Mercy Mosque, its prayer hall is adapted from a church, and like Nawaz, Sibyot also came to Regina a decade ago. |

She plays Rayyan, a devout, feminist physician who has become something of a role model for young Canadian Muslim women. Hewitt says that, although she grew up as the daughter of immigrants in a tiny Ontario town, she also spent a great deal of her childhood in the mountains of Pakistan and with her extended family in Lahore while her mother did fieldwork for her doctorate. She says it’s “fortuitous” that she can “bring something of my past and heritage” to the show.

Rayyan’s on-air father is Yasir, a Lebanese contractor played by Carlo Rota, who also has a leading role as Morris on the US hit show 24. “This show is so different. Its subject matter really needed to be broached, and I wanted to be in,” says the actor, who was born in London of Italian background, but who has also spent time in Cairo. Yasir, he says, is not a man defined by religion. “The character I play I know absolutely. He’s a friend of mine. [He is] a family man, in the community, and he’s part of a minority group, but at the same time he is trying to fit in, trying to make ends meet. He gets up, goes to work, pays his taxes.”

The on-set accents of the other two main Muslim characters—Baber, the conservative economist and Fatima, the sharp-tongued diner owner—are so spot-on authentic that it’s a shock when actors Manoj Sood and Arlene Duncan drop character and revert to their native Canadian. Sood was born in Kenya to Hindu–Sikh Punjabi parents from Pakistan and India, so for him it’s an easy stretch playing a Muslim Punjabi: In accent and otherwise, he says, “Punjabis are the same people.” Sood’s Baber is sometimes referred to as the Archie Bunker of the show, “pompous and hard-headed, off the boat and not well integrated into Canadian society.” Sood is the first to admit that Baber is “nothing like me,” but he feels Baber is redeemed by a clueless but loving relationship with his daughter Layla, played by 15-year-old Aliza Vellani.

|

| While on assignment for this story, photographer Michael Nelson joined Regina drivers in braking for geese, creating one more cultural encounter on the Canadian prairie. Laughter is "a milestone signaling acceptance," says Michael Molloy, former ambassador to Jordan. |

Arlene Duncan has a face that always looks as though it’s about to break into a laugh. Her mother is Jamaican, and Duncan can trace her lineage on her father’s side back to the Underground Railroad that brought escaping slaves to Canada. She says that, although her character is defined by the show as the conservative foil to the more modern Rayyan, this is a bit misleading. As a Nigerian–Canadian character, she says, Fatima “doesn’t have to protest. She left her homeland, set up a business, and the rest of the community embraced that business. She’s a single mother, an independent working woman, and she’s in full ethnic garb every day—hasn’t compromised in any way. How much more independent and liberated can you be?” Duncan maintains Fatima’s accent by watching Nigerian “Nollywood” movies and soap operas on her laptop.

But it takes a visit with Sheila McCarthy, who is one of Canada’s top stage and screen actors, to fully bring home that this is, after all, a Canadian comedy. She plays Yasir’s convert wife, Sarah, with disarming honesty. “I didn’t know a thing about Islam before I got the role, and it’s delicious to play. It’s terrible fun not being a good Muslim wife.”

etween repeated takes outside the “Mercy Mosque,” Michael Kennedy, who directed Little Mosque’s first season, says that, in the second season, he’s “having a ball.” But his enthusiasm didn’t come all at once.

etween repeated takes outside the “Mercy Mosque,” Michael Kennedy, who directed Little Mosque’s first season, says that, in the second season, he’s “having a ball.” But his enthusiasm didn’t come all at once.

|

| Hewitt, McCarthy, Rota, Nawaz, Shaikh and Sood. “The program has something to say that is true,” says Nawaz. |

“When I was told the title and concept,” he says, “I thought, ‘It’ll be funny for a little while. Maybe for one show it’ll be funny.’” But then, as he read the pilot scripts, he realized the concept had legs. Behind its unique religious hook, he explains, “it’s actually structured and written as classic sitcom with classic comedic concepts: husband-and-wife, father-and-daughter, boss-and-assistant relationships, friends who are very different but respect each other’s flaws—what all sitcoms are based on and anybody can relate to.” People tune in, he says, “because it’s so unique,” but they return “because it is so familiar.”

Leo, the comedy guy at the CBC, adds that attaining this familiarity is a challenge because, to most Canadians, “Muslim culture is so new. We’re entertaining Muslims inside Canada by presenting Muslims put into comedic situations. There are no short-hands, no shortcuts. I think some of what we’re doing is maybe more subtle in comedy because, in the pop culture context, there’s a lack of history with Muslims.”

|

| Rota and Hewitt read a teaser spot for the show from cue cards. |

Canadian critics came out with thumbs both up and down. John Doyle, TV critic for the Toronto Globe and Mail, is a fan, and he calls Little Mosque “a softer comedy, not viciously satirical.” In the US, he says, “this show would be outrageous and avant-garde,” but in Canada, “it’s not.” Margaret Wente, a columnist at the same newspaper, pans the show, calling it “so risk-averse, so painfully correct, it makes your teeth ache.”

But Little Mosque looks poised for a nice run this year. Nawaz hopes it will hold onto the magic it created in its first season. “There is substantive value to the show, and it is very funny,” she believes. “Those two go together.”

And Nawaz adds that Muslims all over the world are watching, and discussing the issues raised in the show, because segments of Little Mosque are on YouTube.com.

Regardless how many seasons Little Mosque endures, Michael Molloy, a former ambassador from Canada to Jordan, observes that immigrants “have really arrived when they start to project their Canadian experience through things like Little Mosque on the Prairie. It shows they have the confidence to laugh at Canada and to laugh at themselves as they cope with Canada. At the same time, the rest of the country laughs along with them, and that is a milestone.”

|

Sheldon Chad ([email protected]) is an award-winning screenwriter and journalist who recently returned to Montreal, his hometown, from Los Angeles. He has traveled extensively throughout the Middle East. |

|

Michael Nelson ([email protected]) is the Middle East regional photo manager for the European Pressphoto Agency (EPA) in Cairo. |