n his retelling of Moorish legends and traditions in The Conquest of Granada (published in 1829) and The Alhambra (1832)—both instant best-sellers and widely re-printed—Irving singlehandedly invented “maurophilia,” the western infatuation with al-Andalus—that part of the Iberian Peninsula ruled for nearly 800 years by Arabs—and with all things Arab in Spain. Without Irving’s eye, we might not have had David Roberts’s watercolors (his Spanish Series) nor Owen Jones’s patternbooks (Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra); without his ear, we might not have had Claude Debussy’s suite La Soirée dans Grenade nor even, more recently, Salman Rushdie’s novel The Moor’s Last Sigh. Without Irving, British painter John Frederick Lewis and French poet Théophile Gautier might never have been tempted to visit Moorish Spain, from where they traveled to Egypt and the Levant to do their best work.

n his retelling of Moorish legends and traditions in The Conquest of Granada (published in 1829) and The Alhambra (1832)—both instant best-sellers and widely re-printed—Irving singlehandedly invented “maurophilia,” the western infatuation with al-Andalus—that part of the Iberian Peninsula ruled for nearly 800 years by Arabs—and with all things Arab in Spain. Without Irving’s eye, we might not have had David Roberts’s watercolors (his Spanish Series) nor Owen Jones’s patternbooks (Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra); without his ear, we might not have had Claude Debussy’s suite La Soirée dans Grenade nor even, more recently, Salman Rushdie’s novel The Moor’s Last Sigh. Without Irving, British painter John Frederick Lewis and French poet Théophile Gautier might never have been tempted to visit Moorish Spain, from where they traveled to Egypt and the Levant to do their best work.

According to Holly Edwards, an author and the curator of a 2000–2001 traveling exhibition on American orientalism, Irving was the first 19th-century writer “to pry the Islamic Orient from a harping negativism and to present it as very positive…. Moorish Spain is classicized, and together with the logical, rational, progress-oriented and time-oriented Anglo world of Irving, forms the jaws of a vise between which contemporary Spain and Spanishness are squeezed.”

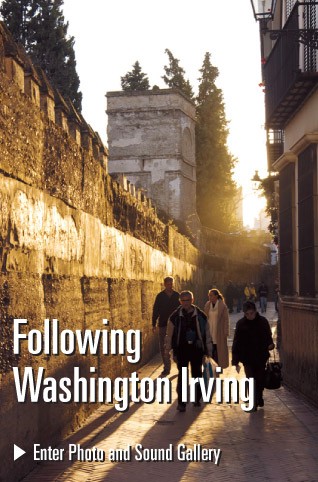

To test that theory, this clock-watching, lead-footed American traveler recently set off in Irving’s footsteps, following the 250-kilometer (155 mi) route he took in May 1829 from Seville eastward to Granada, to seek out the same memories and monuments of al-Andalus that he had come upon 180 years before. Irving rode a mule and spent six days on the road; I chose as my mount a subcompact Citroën, capable of making the Seville-to-Granada run along the A-92 autopista in three hours. But I elected to slow down, to drive the back roads and to take along four books of particular value.

One was the 1851 edition of Irving’s The Alhambra, which expands on the first edition of 1832, including an introductory chapter entitled “The Journey” and describing—“with the keen relish of antiquarian research”—his adventures along the way with innkeepers, peasants and smugglers, with stops in and between Alcalá de Guadaira, Osuna, Antequera, Loja and the Vega of Granada.

The second was Richard Ford’s Handbook for Travellers in Spain (1845), based on that Englishman’s two years and 3200-plus kilometers (2000 mi) of Spanish travels, during which he struggled to find decent meals and clean beds along the same route three years after Irving. Ford called it “the lair of wolf and robber… on what can scarcely be called a road” and strongly recommended alternate itineraries, one via Córdoba by coach (“best for the ladies”) and another down the Guadalquivir River and along the coast by ship.

The third book was the Diccionario de Arabismos by Federico Corriente (1999), an indispensable guide to the Arabic origins of Spanish words, from abalgar (a purgative, from the Arabic habb al-ghar, or seed of the laurel tree) to zanahoria (carrot, from the Andalusian Arabic al-safannaryah, a corruption of the ancient Greek staphyline agria) and naturally passing through all the “al-” Spanish words known even in English, like albacore, alcatraz and alfalfa, concluding with an intriguing section on “false arabismos”—all in all, an amusing way to pass the time at rest stops.

My final choice was a modern guidebook, The Route of Washington Irving, published by El Legado Andalusí, a Granada-based cultural organization, which describes the Arab character of the small towns en route and their history, gastronomy and architecture, capped by descriptions of Seville and Granada themselves as Irving himself would have encountered them.

Irving felt himself almost more in Arabia than in Spain on this trip. Describing the lonely views of herdsmen and mule trains crossing a distant plain, he wrote, “thus the country, the habits, the very looks of the people, have something of the Arabian character…. The dangers of the road produce a mode of travelling resembling, on a diminutive scale, the caravans of the East.” And he found the past very much alive. “Every mountain summit in this country spreads before you a mass of history,” he wrote to a friend, “filled with places renowned for some wild and heroic achievement.”

Irving felt himself almost more in Arabia than in Spain on this trip. Describing the lonely views of herdsmen and mule trains crossing a distant plain, he wrote, “thus the country, the habits, the very looks of the people, have something of the Arabian character…. The dangers of the road produce a mode of travelling resembling, on a diminutive scale, the caravans of the East.” And he found the past very much alive. “Every mountain summit in this country spreads before you a mass of history,” he wrote to a friend, “filled with places renowned for some wild and heroic achievement.”

Irving had been in Seville for some months reading and documenting Spanish history. The author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow had earlier accepted a position as attaché at the United States legation in Madrid, where he produced a biography of Christopher Columbus. Now he was working on his book about Granada, as well as a follow-up volume on the travels of Columbus’s companions, and living at No. 2 Callejón del Agua, just across a wall from the lush Alcázar Real gardens, enjoying an enclosed patio with lemon and orange trees that can still be glimpsed through the wrought-iron door. He does not say so, but given his interest in the region’s Moorish heritage he would surely have visited the Aljarafe (the name comes from al-sharaf, meaning “elevated land”), a farming region west of the city, and the town of Aznalfarache (from hisn al-farsh, “castle of the carpet”), the favorite retreat of the Almohad caliph Yaqub al Mansour, builder of the Giralda in the late 12th century.

Irving’s first stop was the town of Alcalá de Guadaira (from al-qala’a, “citadel,” and wadi elided with al-shari’a, “water supply”), just across the Guadalquivir (wadi al-kabir, “big river”). “Here we halted for a time,” he wrote, “at the ruins of the old Moorish castle, a favorite resort for picnic parties from Seville…. The walls are of great extent, pierced with loopholes, inclosing a huge square tower or keep, with the remains of masmoras or  subterranean granaries.”

subterranean granaries.”

I myself got caught in morning traffic and lost in Seville’s industrial sprawl, which now spills across the Guadalquivir, but I finally parked my Citroën along the Avenida Tren de los Panaderos on the banks of the Guadaira, now a tame little stream dotted with the water-powered flour mills, often painted by the Spanish baroque artist Bartolomé Murillo, that still bring breadmaking fame to Alcalá.

“Here live the bakers who furnish Seville with that delicious bread,” Irving wrote, “known by the well merited appellation of pan de Dios.” And here he may have tasted two breads with Arabic etymologies—acemites, unleavened rolls (from samid, “semolina”), and albardas, or “packsaddles,” from the Arabic word al-barda’ah, of the same meaning.

Irving also noted here the great tanks or reservoirs of Moorish construction that supplied Seville its water by aqueduct. The importance of Arab hydrology was great enough to be recognized in the Capitulations of 28 November 1491, which dictated the terms of surrender of the king of Granada, Muhammad XII Abu ‘Abd Allah (known to the Spanish as Boabdil or El Rey Chico, “the Little King”) to King Ferdinand. Clause 44 states that no changes would be made in the existing water-supply and irrigation systems, and that anyone who disturbed them after the handover would be severely prosecuted.

Irving left Alcalá, following the Guadaira upstream to what was then the hamlet of Gandul, a Spanish word for “slacker” or “idler” derived from the Arabic ghundur, meaning “chubby.” The Spanish meaning was not misplaced, for Irving noted that the town clock “only struck at two in the afternoon, and between those hours one had to guess the time. We guessed it was time to eat, so, alighting, we ordered a repast… and the millers sat down and smoked with us, for the Andalusians are always ready for a gossip.” Gandul’s hacienda now belongs to a marquesa who, according to a surly stableboy, “only comes on Sunday, so, no, because she is not here, I cannot let you in.” Thus I could infer what day it was not, just as Irving had known that it was not two o’clock. I contented myself with visiting the farm’s Almohad-era watchtower, now used as a sheep stall.

It was nearing midday, so I hurried along to Arahal, whose name is appropriately derived from al-rihal, a “stopping place.” Irving had arrived after sunset in the rain, and found the town “of the kind easily put in a state of gossip and wonderment” by the appearance of foreigners. His passport perplexed the townsmen, while “an Alguazil [a minor Spanish official, from al-wazir] took notes by the dim light of a lamp.” Irving described an impromptu concert organized by the innkeeper as “a study for a painter: the picturesque group of dancers,… the peasantry wrapped in their brown cloaks, nor must I omit to mention the old meagre Alguazil, in a short black cloak… diligently writing by the dim light of a huge copper lamp that may have figured in the days of Don Quixote.”

I could find no restaurant willing to serve me lunch on the sand-covered main plaza, which looked more like a bull ring than the town’s Constitution Square. “The cook comes later,” said a pensioner sunning himself on a nearby bench. “You should go back out to the truck stop on the A-92.” I persisted, and was finally directed to the downstairs inn of the Peña Betis, a club for fans of one of the Spanish primera liga’s two Seville-based soccer teams. No guitars were strummed in the peña café at lunch hour; instead, a Hollywood western played on the overhead TV. But I did eat well.

As did Irving, I too arrived at five o’clock in Osuna, the next town on, which, according to his tally then and my reading of the census now, has gained exactly 2306 inhabitants in the intervening 180 years. “Everyone eyed us askance as we entered,” Irving wrote, “as Spaniards are apt to regard strangers.” He quickly made friends by passing cigars all round, which Richard Ford’s Handbook also recommended to break the ice in sullen Spanish towns: “Whether at the bullfight or theater, lay or clerical, wet or dry, the Spaniard during the day, sleeping excepted, solaces himself when he can with a cigar.”

Irving mentioned “a church and a ruined castle” atop the town hill—the Collegiate Church housing the Duke of Osuna’s family crypt and the 12th-century Almohad keep, called the Torre del Agua for the spring flowing from its basement—but he failed to note the six lovely marble columns dating to the Nasrid period (1238–1492) in the crypt or the Torre’s elegantly vaulted upper rooms. But for one weary motorist who had just parked his Citroën, a plate of oxtail cooked four ways at the mesón de la consolación and the stout welcome offered to a newly converted Betis fan did more to break the ice than even two boxes of the best habanos would have done.

Leaving town at an early hour, Irving wrote that he “entered the sierra, the road wound through picturesque scenery, but lonely… a wild and intricate country with its silent plains and valleys intersected by mountains.” This was the home territory of the infamous ninth-century brigand Omar ibn Hassan, who disputed dominion even with the caliphs of Córdoba. Six hundred years later, this same upland stretch fell into the hands of Ali Attar, alcayde (from al-qa’id, meaning “leader”) of Loja and father-in-law of Boabdil, and thus, according to Irving, was still known as “Ali Attar’s garden.”

After the mountains of Sierra de los Caballos and past the Fuente la Piedra’s salt lake, the next town along the way is Antequera, which Irving called “that old city of warlike reputation, lying in the lap of a great sierra which runs through Andalucia….” Men here still wore the montero, an ancient hunting cap, he wrote, and “the women too were all in mantillas [lace shawls] and basquiñas [long skirts]. The fashions of Paris hadn’t reached Antequera.”

Irving took a dawn stroll up Antequera’s hilltop to the Alcazaba (from al-qasabah, “fortresses”). “Below me,” he wrote, “in its lap of hills, lay the old warrior city so often mentioned in chronicle and ballad…. To the right the Rock of the Lovers (Peñon de los Enamorados) stretched like a cragged promontory into the plain, whence the daughter of the Moorish alcayde and her lover, when closely pursued, threw themselves in despair.” Even Christopher Columbus, in his ship’s log, compared a New World headland to this widely known landmark, and the legend keeps Antequera on the tourist map today. Richard Ford, meanwhile, made it something British, writing that it “rises like a Gibraltar out of the sea of the plain.” For me it was shrouded in morning fog.

Where in Ford’s time the local governor could be found dismantling the mosque to resell its bricks and pocket the cash—“Cosas de España!” (“Things in Spain!”), he wrote—today the Andalucian regional government, with help from the European Union, is painstakingly restoring the citadel’s two Almohad towers, the Torre Blanca and the Torre de Homenaje, whose clock timed the irrigation rights to the canals fed by the Guadalhorce River (from either wadi al-faras, “river of the horse,” or wadi al-haras, “river of the guard”).

Ten minutes on the A-92 got me to Irving’s next stop, Archidona, “situated in the breast of a high hill with a three-pointed mountain towering above it and the ruins of a Moorish fortress,” wrote Irving. “It was a great toil to ascend a steep stony street leading up into the city, although it bore the encouraging name of Calle Real del Llano [Royal Street of the Plain].” The fortress now has a paved road to the top, a full 300 meters (1000') above the town, and a former Almohad mosque retains its original three horseshoe-arched bays supported by Roman columns, some elegantly fluted on the spiral.

Irving cannot refrain from retelling apocryphal legends, and here he wrote of a besieged Moorish king who looked down upon the invading forces of Queen Isabella and laughed at her in scorn because he thought his citadel to be invincible. But Isabella had been shown a secret path, and “when the Moor saw her coming, he was astonished, and springing with his horse from a precipice, was dashed to pieces. The marks of his horse’s hoofs are to be seen in the margin of the rock to this day.”

After much fruitless searching, I could only assume that the fatal hoofmarks are now buried under the concrete foundations of three cell-phone towers that rise nearby. Yet some cosas de España never seem to change: As I searched, an aged shepherd wearing an odd-looking cloth cap—could it be a montero?—moved his flock up the hill to graze among the flowering almond trees just as the Peñon de los Enamorados finally cleared of mist.

Crossing over the Puerto del Rey —in the words of Irving, “one of the great passes into the territories of Granada, and the one by which King Ferdinand conducted his army”—the autopista takes the high route, leaving the town of Loja spread below along-side the River Genil, which flows the length of Granada’s famous Vega, or plain. Loja was called Granada’s “gate and key” by its great native-born polymath Ibn al-Khatib (1313–1374). He described Loja as having “a cheerful face, a fascinating aspect, a river with a copious current, fruitful trees, gardens, fountains, and true delicacies,… women who cure broken hearts… and hares that seem awake when they are sleeping. To get there, one must pass through narrow defiles.”  Ibn al-Khatib clearly prefers his hometown over its rival Archidona, which he dismisses as having “no water, little agriculture, broken homes, lazy inhabitants, scant meat served at table, and shaykhs like goats wearing the skin of men.”

Ibn al-Khatib clearly prefers his hometown over its rival Archidona, which he dismisses as having “no water, little agriculture, broken homes, lazy inhabitants, scant meat served at table, and shaykhs like goats wearing the skin of men.”

Loja’s high walls repulsed King Ferdinand and his English archers for 34 days in a siege in 1488. Irving called it “wildly picturesque…. The ruins of a Moorish alcazar crown a rocky mound which rises out of the center of the town. The river Xenil [Genil in modern spelling] washes its base, winding among rocks and groves and gardens and meadows, and crossed by a Moorish bridge,” as it still is.

In this “wild mountain place, full of contrabandistas, enchanters, and infiernos,” Irving the storyteller found the perfect setting for another infernal tale, in an inn with “swaggering men with long mustaches, who carry sabres as a child does her doll…. A blunderbuss stood in the corner beside the guitar.” Richard Ford wrote a bit less fearsomely on the matter of Spanish guitarists—“the traveller will happily find in most villages some crack performer…. A función will soon be armada, or a party got up of all ages, who are attracted to the tinkling like swarming bees.”

Pilar, owner of Loja’s Posada Rincón, told me that her establishment opened its doors to travelers in 1810, and she recalled when its outer patio had not yet been roofed and was used to stable mules. Loja’s museum has mid-19th-century photos of the town square showing men in gallant dress just as Irving described them, with wide-brimmed hats, tight-fitting riding breeches and short jackets. An engraving dating from 1585 shows the castle walls fully intact, and even David Roberts tried his hand at capturing the citadel’s tower in his Spanish Series.

On television, the nightly half-hour live broadcast of flamenco direct from Seville is followed by a “friendly” soccer match between England and Spain. It attracts most of the Posada Rincón’s guests—some pensioners, some transients. One in particular, who holds the remote control, has an eye-to-chin scar that surely would have scared off Irving’s most ferocious contrabandista.

Yet this was not likely Irving’s inn, “the inhabitants of which seem still to retain the bold fiery spirit of the olden time,” whose name he reported as the Corona. No trace of that posada can be found today even on the barrio alto’s tiny Calle Washington Irving. And at the Rincón, when the final whistle blew with Spain ahead 1–0, my fellow soccer fans were gently snoring and the entire town pretty much shuttered—not quite the fiery spirit Irving had reported.

Some things in the town remain unchanged, however. In the Alfaguara quarter (“bountiful spring” in Spanish, from al-fawwarah, meaning “jet of water”), Loja’s most famous fountain, with 25 spouts, continues to fill its stock trough, plenty for both Irving’s long-eared mule and the Citroën’s 75 horses, confirming Ibn al-Khatib’s praise for his town’s “copious currents” more than a half millennium ago.

The next day, Irving entered onto the Rio Genil’s table-flat plain. He called it the “far famed” Vega de Granada and stopped at midday in the Soto de Roma, “a classical neighborhood…, a rural resort of the Moorish kings, in modern times granted to the Duke of Wellington.” His muleteer and majordomo Sancho set out one last picnic beside a stream, and seen “in the distance was romantic Granada surmounted by the ruddy towers of the Alhambra, while far above it the snowy summits of the Sierra Nevada shone like silver.”

I was caught in the rain here, so no summits shone like silver for me, yet I determined to find the Almohad watchtower known as the Torre de Romillo, the only one still standing on the Vega, now alongside an asparagus farm. Workmen were busy securing its cracked walls, but they told me with some excitement that an archeologist from Granada had just discovered a ceramic-tiled well under a meter (39") of earth in its basement. The tower would have been newly built and its well still full in the year 1319, when, according to Ford, 50,000 soldiers died in a battle here between Muslims and Christians.

In the nearby town of Chauchina, outside the parish church, stands a broken column from a local quarry. Destined for the Alhambra’s Palace of Carlos V, it tumbled off a transport wagon in the mid-16th century and was left behind. Its 32 perfectly matched sister columns, one of which no doubt is Chauchina’s hurriedly cut replacement, still support the palace’s second-floor arcade.

Approaching the fabled city of Granada, Irving was steered by a wily tout to what he promised was the city’s best inn, with chocolate con leche (hot chocolate made with milk), camas de luxo (soft beds) and colchones de pluma (feather pillows). “Ay, señores,” he told Irving and Sancho, “you will fare like King Chico in the Alhambra.” But this proved another cosa de España. “We found before morning,” Irving wrote, that “the little varlet, who was no doubt a good friend of the landlord, had decoyed us into one of the shabbiest posadas in Granada.”

Yet Irving’s diary entry for May 31, 1829 recounts the happiest of endings to this story. “You will I am sure congratulate me upon my good luck—Behold me, a resident of the Alhambra, even in the old Moorish palace of Boabdil!” He goes on to explain how the governor of Granada had invited him to lodge in some unused rooms of the palace itself. “We gladly occupied it and here I am, as much a sovereign of the Palace as Rey Chico.”

Irving stayed through the summer and wrote much of The Alhambra there, inspired by midnight walks through “these great halls and courts and gardens” and conversations with a fellow guest, a certain “Moor of Tetuan,” who translated for him the “aroma of the poetry” inscribed on its walls. A modern traveler, though he may have the best connections, is rarely invited to overnight in the Nasrid Palace—not even in the two side rooms that Carlos v redecorated in Spanish style in the 16th century and where Irving slept 200 years later.

On the route from Seville, I had found Irving accurate about many things, but in this day of 120-kilometer-per-hour (75-mph) autopistas and cell phone reception all along the A-92, it is no longer true, as he wrote, that the route makes for “tedious travelling through a lonely and dreary country.” But he was right on target in his next observation: “Granada, however, repays one for every fatigue.” It certainly did for mine.

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a writer and filmmaker living in New York. He recommends that all travelers to Spain read Don Quixote before setting out. |

|

Tor Eigeland (www.toreigeland.com) has photographed for Saudi Aramco World for more than 40 years. Though he has traveled the world, al-Andalus remains one of his favorite subjects. |