|

|

| EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY LIBRARY / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

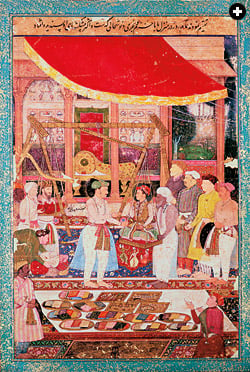

| Depicting a ceremony that already lay three centuries in the past, an illustration from Rashid al-Din’s 14th-century Jami‘ al-Tawarikh (Universal History) shows Mahmud ibn Sebuktekin, the first independent Ghaznavid ruler, receiving a richly decorated robe of honor from the caliph. |

|

n 1332, that most famous of medieval travelers, Ibn Battuta, stood before the Sultan of Delhi in a vast hall called Hazar Ustun (Thousand Pillars). It was an imposing scene. “The pillars are of painted wood and support a wooden roof, most exquisitely carved. The sultan sits on a raised seat standing on a dais carpeted in white, with a large cushion behind him and two others as arm-rests.” A hundred guards flanked the sultan. Facing him were his highest officials and nobles, each in an elegant silk robe. On each side was a row of judges and teachers, and farther back in the hall were distant relatives of the sultan, lower-ranking nobles and military leaders—all of them also dressed in luxurious silk robes.

n 1332, that most famous of medieval travelers, Ibn Battuta, stood before the Sultan of Delhi in a vast hall called Hazar Ustun (Thousand Pillars). It was an imposing scene. “The pillars are of painted wood and support a wooden roof, most exquisitely carved. The sultan sits on a raised seat standing on a dais carpeted in white, with a large cushion behind him and two others as arm-rests.” A hundred guards flanked the sultan. Facing him were his highest officials and nobles, each in an elegant silk robe. On each side was a row of judges and teachers, and farther back in the hall were distant relatives of the sultan, lower-ranking nobles and military leaders—all of them also dressed in luxurious silk robes.

The sultan honored Ibn Battuta and his companions in a ceremony familiar to every member of the court: They were conducted to an adjacent robing hall, where each donned a new shirt, sash, pants, turban, shoes and outer robe. They emerged to the acclaim of the assembled nobles, and were then deemed “suitable” to take their places in court. It was a good day for both Ibn Battuta and his companions: The sultan also offered all of them employment.

|

| TEXTILE MUSEUM |

| This fragment of a robe of honor dates to about the year 1000 in Baghdad. Sewn into it is a certificate of office: “For the use of Abu Said Zandanfarruk ibn Azamard, the Treasurer.” |

More than six centuries later, in 1973, my wife, Sara, and I ventured overland from Istanbul to Delhi, following some of the same roads traveled by Ibn Battuta. At Herat, in western Afghanistan, Sara met a group of women and, although they shared no common language, accompanied them over several days while they bought and sold in the markets. They liked Sara, and on the day we left the city, they insisted that she accept an antique, fully embroidered black cloak. They showed her how to wear it and with gestures suggested that she do so always. And so the cloak became her outer garment all across Afghanistan, with the unexpected result that Sara was treated with the greatest respect in bazaars, shops and all public spaces. Weeks later, in Kabul, someone explained to us that the cloak’s embroidered patterns signaled that the wearer was under the protection of one of the most powerful border tribes of western Afghanistan, and thus anything less than courtesy might provoke retaliation. I have been fascinated by the power of ceremonial robing ever since.

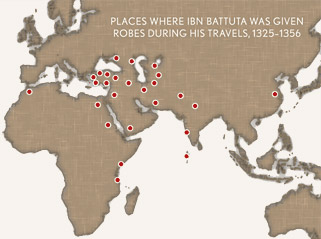

Ibn Battuta grew up in Morocco, and the sultan was from Delhi, more than 6400 kilometers (4000 mi) away by the caravan routes of the time. Yet both knew the details and significance of the system of honor and service that centered on the giving and receiving of elegant robes. The ceremony had an Arabic name: khil‘a; in Persian, it was called sar-o-pah, “from head to foot.” Ibn Battuta learned about it and participated in it during eight years of travel by caravan, ship, horse and oxcart, all across the Middle East, Persia, the Caucasus and the area that is today Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

In Egypt, he wrote, “I stayed with the Shaykh Qutb al-Din in his hospice for 14 days, and what I saw of his zeal for the poor brethren and the distressed, and his humility toward them, filled me with admiration. He went to great lengths in honoring me, showed me generous hospitality, and presented me with a fine set of garments.”

In Tabriz, in western Iran, “This amir told the sultan [Abu Sa‘id] about me and introduced me into his presence. He asked me about my country and gave me a robe and a horse.”

In Mogadishu, East Africa, “one of the shaykhs came to me, bringing me a set of robes…. They also brought me robes for my companions suitable to their position.”

In Constantinople, “the Christian Emperor was pleased with my replies and said to his sons, ‘Honor this man and ensure his safety.’ He then bestowed on me a robe of honor and ordered for me a horse with saddle and bridle, and a parasol of the kind that the ruler has carried above his head, that being a sign of protection.… It is one of the customs among them that anyone who wears the ruler’s robe of honor and rides on his horse is paraded through the city bazaars with trumpets, fifes and drums, so that people may see him.”

And what textiles these robes of honor were! Ibn Battuta paid attention to the type of cloth and origin of the robes he received. For example, in Mogadishu, honorific robes consisted of “a silk wrapper which one ties around his waist in place of drawers (for they have no acquaintance with these), a tunic of Egyptian linen with an embroidered border, a furred mantle of Jerusalem stuff, and an Egyptian turban with an embroidered edge.” Clearly, this was purely court dress, a sign of one’s standing.

|

| STEWART GORDON |

| The embroidery patterns on this robe, given as a gift in 1973 to Sara Gordon, the author’s wife, indicated that the wearer was under the protection of one of the most powerful tribes of western Afghanistan. |

At Izmir, on the Aegean coast of present-day Turkey, the sultan sent Ibn Battuta “a Greek slave, a dwarf named Niqula, and two robes of kamkha, which are silken fabrics manufactured at Baghdad, Tabriz, Nishapur and in China.” The warp of these robes from China could have been silk or cotton, but the weft thread was gold: The first syllable of kamkha is derived from chin, the Chinese word for “gold.” By the time Ibn Battuta reached Delhi, he had chests full of robes.

In the same years that Ibn Battuta received robes during his travels, the Sultan of Delhi lavishly and regularly bestowed them in khil‘a ceremonies. He gave out close to 200,000 robes annually to his family and nobles, to generals, ambassadors and bureaucrats. The silks came from China, the Middle East, Egypt and his own workshops. In addition to regular festivals, the sultan also bestowed robes on various special days, such as his return from a journey, the return of a son from a military campaign, at the birth of a son, at marriages or on birthdays. These regular robing occasions created solidarity among the courtly elite, an inclusive, visible “suitability” for presence at court.

Some robes, fabricated in royal workshops for a single occasion, were so fabulous that they constituted a significant transfer of wealth. Such was the robe Ibn Battuta saw the Sultan of Delhi give his future brother-in-law before his wedding. It was “…a ceremonial robe of blue silk embroidered and encrusted with jewels; the jewels covered it so completely that its color was not visible because of the quantity of them, and it was the same with his turban. I never saw a more beautiful robe than this one.”

To add to the significance of the royal gift, robes were often brushed against the shoulder of the sultan before being bestowed, investing them with the baraka—literally, “blessing”—and thus the essence of the king. Whether silk or velvet, with or without gold or jewels, robes given in the khil‘a ceremony connected the ruler and the physical body of the recipient in this most intimate way.

Both Ibn Battuta and the Sultan of Delhi knew how important the ceremony was to their world, but neither probably knew its origins. Nor do we. With silk, horses, ideas and much more moving up and down the Silk Roads for centuries, it is probably futile to look for a single “origin” for the khil‘a ceremony. Still, some possibilities have emerged from research over the past decade.

Both Ibn Battuta and the Sultan of Delhi knew how important the ceremony was to their world, but neither probably knew its origins. Nor do we. With silk, horses, ideas and much more moving up and down the Silk Roads for centuries, it is probably futile to look for a single “origin” for the khil‘a ceremony. Still, some possibilities have emerged from research over the past decade.

In Persia, luxurious silk robes were in use quite early. Alexander found thousands of them when he conquered Persepolis around 333 BC. Unfortunately no sources describe who wore the robes or how they were used or whether they were bestowed on nobles.

More substantive is an incident in the Book of Esther, one of the last books of the Old Testament. Scholars generally agree that this book is a work of historical fiction, set in Persia, and written around the first century BC. In the story, King Ahashuerus rhetorically asks what a suitable ceremony of honor would be. Haman, his chief minister, replies:

“Have them bring a royal robe that the king has worn and a horse that the king has ridden, one with a royal crown on its head. Then have them hand the robe and the horse over to one of the king’s most noble princes and have him robe the man…and have the prince lead him on horseback through the city square.”

This ceremony is strikingly similar to what Ibn Battuta experienced in Constantinople more than a thousand years later.

The ceremony also appears in Chinese literary sources of the first centuries of our era. Only recently has the historian Xinru Liu figured out that China needed horses and cattle from the nomads of the eastern steppe, and the nomads needed food and iron from China. War, in which each side seized what it needed, was frequent, but in periods of peace, there was trade and diplomacy in which silk robes played a crucial role. Only China produced silk, and political leaders in China gave this valuable cloth to nomad chiefs on cessation of hostilities, for protection and as dowry. The chiefs, in turn, bestowed the robes on their leaders to demonstrate their own power and to build loyalty: These elegant robes came only from the hands of the chiefs; they differentiated the chosen leaders from common soldiers and, with every wearing, the robes reminded the leaders whom they served.

This explanation of the origin of khil‘a is attractive. Robing in these early nomadic steppe bands has the essential features of the khil‘a ceremony wherever it was found over the next 15 centuries. Presentation was highly personal, either from the hand of the king or brushed against his body; the ceremony took place before an assembled group of nobles, who were dressed in luxurious robes themselves; and the honored one then took his place among them. Robes were bestowed in conjunction with other specific gifts—horses, decorated horse trappings, gold, slaves and weapons (especially jeweled swords). These items were foundations of wealth in the culture of steppe nomads, whether gained through trade or war.

Finally, the robe of the khil‘a ceremony was always a sewn garment, and it generally had slits in the back or sides to make it wearable while riding. The significance of this comes in contrast to the wrapped garments typical of India, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, such as the dhoti, lungi and sari, all of which require frequent adjustment, and none of which can be worn while riding a horse.

|

| BRITISH LIBRARY / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| Although the main focus of this gouache miniature, dated circa 1615, is the weighing of the prince against gold and silver to be distributed to the poor, it also shows, in the foreground, several dozen robes of honor, folded and arranged on trays. The painting appears in the now-dispersed Tuzuk-i Jahangir (The Memoirs of Jahangir). |

Even though the evidence of the khil‘a ceremony is much clearer in the period after 600, research on the ceremony remains limited to snapshots of khil‘a at particular times and places. Honorific robing became standard courtly practice in China when nomads became rulers inside the Great Wall, and various colors became associated with ranks within the nobility. Similar ceremonies spread to Korea, Japan and Sinicized Vietnam.

There is good evidence for khil‘a-style investiture in Persia during the Sassanian period, in the fourth to seventh centuries. In a yearly cycle, the king bestowed on his nobles robes he had worn, together with weapons, gold, silver, jewels and horses.

In the Byzantine Empire, complex robing replaced simpler Roman ceremonies for accession to church office, ambassadorial exchanges, bureaucratic promotion and personal recognition by the emperor. Traders brought a ready supply of luxurious and expensive textiles both from China and from looms in such caravan cities as Bukhara and Tashkent. Scholars Elizabeth Jeffreys and Roger Scott noted that in 520, Emperor Justinian won over the queen of the Sabir Huns with a presentation of imperial robes, along with “a variety of silver vessels, and not a little money.” As the Byzantine Empire expanded, the ceremony spread to the entire Black Sea region, present-day Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Greece, Egypt and some of the North African coast.

By the late seventh century, the khil‘a ceremony was everywhere in the cultural world into which Islam spread. Early Muslim leaders used robes to reward successful generals. With the rapid political and military spread of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries, formal honorific robing reached the coast of North Africa and Spain.

As had been the practice in Southwest Asia for centuries, the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, who ruled from about 750 to 1238, used robes to promote administrators, honor successful commanders and reward the nobility. Like the Byzantines, the Abbasids also used robes on ambassadorial missions to establish alliances. In mid-June 921, a courtier named Ibn Fadlan led one such mission, departing Baghdad with gifts that included elegant silk robes.

He struggled through cold, negotiated with hostile nomads and finally reached his destination on the banks of the Volga River in what is today Russia. There, too, both sides understood the implications when the Bulgar king Almish put on the caliph’s robe, which he did with great ceremony before his nobles: The robe placed Almish in the sphere of the caliph’s authority, and it triggered expectations of alliance and fealty.

At this historical distance, it is impossible to know whether khil‘a became a common system of honor through the coalescing of local customs or because rulers made conscious choices to adopt the ceremony. The truth probably lies somewhere in between, but certainly kings were always on the lookout for customs and ceremonies that would aid their rule. For example, in 1275, during Marco Polo’s first audience with Kublai Khan, the first subject that the khan wanted to discuss was how, in Polo’s lands, kings “maintained their dignity.” He was looking for customs or ceremonies that might strengthen his position. Equally clear is that part of the value kings placed on travelers like Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo was that they brought knowledge of royal ceremony from faraway places.

Khil‘a thus became a network of ceremony that crossed boundaries of religion, region and ethnicities. Just as it was practiced in Christian Constantinople and Confucian China, so was it practiced in animist Central Asia. Following the extraordinary success of Genghis Khan and his successors a few decades before Ibn Battuta’s travels, lavish robes became de rigueur at the Mongol court. For state occasions, nobles were required to wear a cloth-of-gold robe received from the khan. In the succession wars following Genghis Khan’s death, observed historian Thomas Allsen, these robes were so important that claimants to the throne sometimes seized the artisans capable of crafting them.

|

| ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM |

| Above: This robe was presented in 1869 by Yakub Beg, ruler of Kashgar (now in Xinjiang, China) to British emissary Robert Shaw. Below: To the east, China was a source of both robes and material for them. This Chinese robe of honor is on display at the Nanjing Museum. |

|

| CHINA NEWSPHOTO / CORBIS |

Muslims of the 12th and 13th centuries brought the custom to India, which had long produced silk fabrics, and there Hindu rulers readily adopted it. Yet acceptance of the khil‘a ceremony into the courts of India had to overcome two problems: Hindu kings were, by and large, of middling or lower caste, and their clothes, by caste rules, should have been polluting to higher castes. This first problem was apparently not too difficult to solve: At the practical level, there seems to have been a widespread belief that it was not useful to look too closely into the family origins of kings—and, in any case, newly ascended kings often created myths of their dynasty’s divine origin to bolster their ritual position; descendents of gods could hardly be questioned. The second problem regarded how the king should be clothed. There was also a long tradition that the proper presentation of the kingly body was unclothed from the waist up or at most lightly draped with sheer fabric. Within the sphere of Muslim conquest, however, and within a relatively short time, local rulers took up robes that fully covered the body.

By the time Ibn Battuta stood before the sultan of Delhi, the khil‘a ceremony was in use from China to Spain. As Mughal accounts richly document, rulers invested at their pleasure any individual they wished to honor, perhaps a poet for a witty couplet, a wrestler for a good match, a guide who successfully led the royal entourage through a forest or a particularly brave soldier on the battlefield. Stores of luxurious robes were kept at the ready for the ruler’s spontaneous presentation.

Robes were also used diplomatically between rulers. Ibn Battuta names the seven great rulers of his time: the sultan of Morocco, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria, the Mongol Il-Khan of Iraq and Iran, the khan of the Golden Horde, Chaghatai Khan, the sultan of Delhi and the ruler of China. It was honorable and expected that these rulers exchange gifts that demonstrated their wealth and their access to rare and beautiful things—a “circulation of fabulous objects,” as the historian Oleg Grabar called it. Embassies carrying such objects crisscrossed Egypt, Persia, Turkey, Central Asia and India.

Thus the khil‘a ceremony was a system of honor and service that pervaded the upper reaches of societies and established relationships among people who might differ in other ways.

In Central Asia, noblewomen also bestowed khil‘a. When Ibn Battuta left the Golden Horde to accompany a khatun (wife of a khan) to Constantinople, “each of the khatuns gave me ingots of silver…. The sultan’s daughter gave me more than they did, along with a robe and a horse, and altogether I had a large collection of horses, robes, and furs of miniver and sable.” Highly placed women in the courts of Delhi also both gave and received robes: Ibn Battuta noted that he also received a robe from the sultan’s mother.

The closer one looks at the system, the more givers there seem to be. For example, the Geniza documents of the Jewish community in Egypt record that the merchant elders gave out robes of honor to certain non-Jewish merchants.

Muslim Sufi orders ascetically inverted the practice, favoring “robes of simplicity”—the more worn, patched and tattered, the better—to show the wearer’s disdain for earthly pleasures and his focus on the holy life, yet a robe nonetheless carried the baraka of its former possessor, and it was believed to influence the behavior of the recipient. Within the Sufi tradition, therefore, followers expected the robe of a great teacher to deepen the piety and practice of a student. In some orders, presentation of the robe literally passed the mantle of authority to a successor.

|

| LIVRUSTKAMMAREN, STOCKHOLM / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| This coat of cut velvet was made in Iran for the Czar of Russia, who in 1644 gave it to Queen Christina of Sweden. |

Even Ibn Battuta himself bestowed ceremonial robes, at least once giving them to a guide whom he temporarily employed. Unfortunately, on the Malabar Coast of India, Ibn Battuta encountered pirates who stole his entire collection. “They took everything I had preserved for emergencies; they took the pearls and rubies that the king of [Sri Lanka] had given me, they took my clothes and the supplies given me by pious people and saints. They left me no covering except my trousers. They took everything everybody had and set us down on the shore.”

In 1348, Ibn Battuta returned to the Middle East. Later, at Fez, the sultan listened to the stories of his travels and commissioned the memoir that would ensure Ibn Battuta’s place in history. He also honored the traveler with robes.

A little more than 100 years after Ibn Battuta passed through Cairo on his way back to Morocco, the Egyptian Mamluk state used luxury robes for every appointment and promotion. High-ranking military officers received a particularly luxurious robe of velvet with a sable lining. Both viceroys of provinces and less vaunted civilian officials—the superintendent of the harem, the chief treasurer, the supervisor of the royal hospital and various ranks of judges—had to make do with various grades of woolen robes. As we expect from earlier usage, the bestowal of a luxurious robe on a Jewish director of the mint under Sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri (1501–1516) evoked no particular comment: As always, the robe ceremony was about the relationship between a king and those who served him, not religion.

Robes were equally central to the Ottoman court. Shortly before the defeat of the Spanish Armada, for example, robes figured in diplomacy between the Ottomans and England. Both powers had good reason to view Spain as a common enemy. In 1594, Queen Elizabeth promoted the connection by sending presents to Safiye Sultan, mother of Sultan Mehmed III (1593–1603) and one of the most powerful individuals in the Ottoman Empire. Along with a reply to Elizabeth’s letter, Safiye sent “an upper gowne of cloth of gold very rich, and under gowne of cloth of silver, and a girdle of Turkie worke, rich and faire,” plus a crown studded with pearls and rubies. It is doubtful that Elizabeth knew of the khil‘a ceremony or that robes were part of the “circulation of fabulous objects” in the Asian world, but she apparently enjoyed wearing the luxurious Turkish robes. Master politician that she was, Elizabeth probably kept her court and the Spanish spies guessing whether she was signaling a new Ottoman connection or merely enjoying exotic dress.

In India, a half a century later, the meaning of khil‘a was still common currency between the Mughal Empire and its rivals, and from the 1660’s comes an account of the dire consequences of rejecting Mughal robes. In a well-documented incident, Mughal forces surrounded a regionally successful king named Shivaji and escorted him to Delhi, ostensibly to integrate him into the Mughal Empire. In the hall of public audience, officials brought Shivaji forward and robed him. The emperor, however, neither spoke to him nor acknowledged the ceremony; Shivaji was then ushered to the very back of the audience hall. He fully understood the insult, and contrary to court rules, he refused to stand quietly; instead he shouted that he would not stand behind men whose backs he had seen in battle. Receiving no satisfaction, he took off the robe and threw it on the floor, saying, “Kill me, but I will not wear the khil‘a,” whereupon he and his entourage turned their backs on the emperor—a serious breach of etiquette —and stalked out of the hall.

|

| STEWART GORDON |

| Above: French jewel merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier used this etching, showing the robe presented to him in 1652 by Shaista Khan, uncle of the Mughal emperor of India, as the frontispiece of his book Travels in India. Below: Sir Anthony van Dyck’s 1622 portrait of Robert Shirley shows the robe Shirley wore as ambassador of the Safavid court of Persia to England. |

|

| PETWORTH HOUSE / NATIONAL TRUST |

Everyone at court expected them all immediately to be executed, but because of the support of a few high Mughal nobles, Shivaji was merely imprisoned, and he managed, some months later, to escape back to his own territory.

It was only in the 19th century that khil‘a began to disappear. Across the whole of “the robing world,” as part and parcel of colonial domination, European rulers rejected robes and insisted instead on hats and pants. They introduced their own symbols of honor, such as banners for regiments and medals for individuals.

To the lawyers and military men who led nationalist movements of independence, khil‘a soon seemed too redolent of monarchy: old-fashioned and out of step with the fast-changing modern world.

Yet honorific robing in the khil‘a tradition has not entirely disappeared. Tibetan Buddhists regularly place a prayer shawl on one they honor. In India and abroad, Sikhs use a khil‘a ceremony to honor those who serve the religion, such as an activist, writer or politician. Also in India, a luxurious shawl—a pared-down version of khil‘a—often accompanies a cultural award in writing or music. In Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, the foreign head of a successful trade or educational mission may receive a beautiful robe. In a few countries in Africa, honored visitors —US Senator Hillary Clinton was one in 1997—receive and are expected to wear luxurious local robes. Among Sufi teachers, the “robe of simplicity” continues to be favored dress.

Khil‘a has also long been in use, in modified form, in the West. Last spring, my wife once again received a robe of honor, but this time it was not in Afghanistan but in our home state of Michigan. It was at a commencement ceremony where she received her doctoral degree. As the faculty and the new graduates filed in, I suspected that few had any idea why they were wearing the long robes, or why a luxurious velvet hood was bestowed on the doctoral candidates.

Although western academic robes hark back to the medieval European church robes that gave the wearer certain freedoms from civil authority, the deeper history of church robes goes back much further, to the sixth- and seventh-century conflict between Rome and Constantinople. The Eastern Church drew on the khil‘a ceremony and robed its bishops to ensure their loyalty. Rome soon imitated Constantinople with robing of its own. By the end of the sixth century, there were clothing and robing regulations for clerics all across Christendom.

Wherever in the world academic commencement ceremonies include robes, both faculty and graduates are, literally, covered in a tradition almost 2000 years old that connects them with courts and kings from Spain, Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, India and China, and which carry the distant echoes of the Silk Roads and their travelers, like Ibn Battuta.

|

Stewart Gordon is a senior research scholar at the University of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. His recent book, When Asia Was the World (2008, Da Capo; reviewed in the March/April 2008 issue of Saudi Aramco World), is a look at family, trade and intellectual networks across Asia in the years between 500 and 1500. He conducts world and Asian history workshops for high-school and college teachers and lives in Ann Arbor. |