|

|

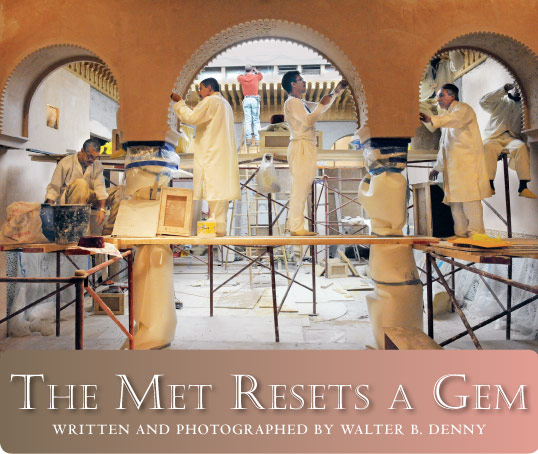

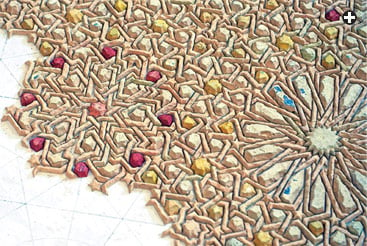

In a dramatic finish to eight years of effort, 11 masters of traditional Moroccan interior

arts spent nearly a year in residence to create the Moroccan Courtyard in the authentic

style of the 14th century, the era that produced the masterpiece mosques, madrassas and

palaces of North Africa and southern Spain.

|

| |

n November,

after an eight-year, $50-million renovation, 15 galleries devoted to "The Arts of Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran,

Central Asia and Later South Asia" will open in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. In what is almost a

new museum within the museum, visitors will view some 1200 of the Met's nearly 12,000 Arab-Islamic works

arranged not chronologically from past to present, but rather as a kind of geographical traverse across places

and cultures.

n November,

after an eight-year, $50-million renovation, 15 galleries devoted to "The Arts of Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran,

Central Asia and Later South Asia" will open in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. In what is almost a

new museum within the museum, visitors will view some 1200 of the Met's nearly 12,000 Arab-Islamic works

arranged not chronologically from past to present, but rather as a kind of geographical traverse across places

and cultures.

This new way of organizing the exhibits, reflected in the long name that omits the word "Islamic," reflects

an evolving emphasis on the diversity that exists within a vast field that includes not only religious art

by Muslims, but also much secular and luxury art by Muslims, as well as art by Muslims for non-Muslims and

vice versa. Among the new cases and spaces are three displays that promise to be especially striking: the

Spanish Ceiling, an elaborately carved, painted and glazed wooden ceiling probably made in the 14th, 15th

or 16th centuries by Muslim artists for Christian patrons; the Damascus Room, an early-18th-century reception

room (qa'a) from a Damascus merchant's mansion; and the Moroccan Courtyard, the Met's newest jewel,

created this year inside the museum in authentic 14th-century style by contemporary artists from Fez, Morocco

who used materials and tools of the era.

|

|

Fifth Avenue, New York, viewed from the temporary elevator that ferried materials to the 15 new galleries.

|

It's fair to ask, however, why the Met has bothered—and why the renovation took eight years—

when the museum was already long renowned for the world's largest display of what was, perhaps too sweepingly,

called "Islamic art." In a world where such cities as Toronto and Doha are building entirely new museums,

and the Louvre in Paris has added a major expansion for arts from Islamic cultures, the Met is different:

It can't expand. Its "footprint" on the east side of New York's Central Park is legally limited, so "building

from within" has been both the Met's motto and its burden for years. Although the renovated and renamed

galleries offer nearly 40 per cent more space, they remain where the original ones were, on the second floor.

The story behind these new exhibition spaces, where I had the privilege to both work and observe over nearly

four years, is one of diplomacy and drama but, above all, of hard work and hard choices.

|

In 2003, the Museum closed its Islamic Galleries to accommodate the long-planned renovations. Because the

mission of a museum is to find new ways to interpret and display art, and thus to produce new knowledge,

the Met took this as an opportunity to re-think and renovate its Islamic-world displays—an opportunity

made all the more important, even urgent, by post-9/11 interest in Islamic cultures. The opportunity came,

however, at a time of internal transition at the Met, and so it was only after some false starts that in

2005, Director Philippe de Montebello appointed Navina Haidar, a promising young associate curator, to direct

the renovation project.

"I knew right away I would need to confront major questions of what 'Islamic art' meant," she says. "And I

viewed the task with a combination of excitement and dread. I also knew I was going to have to learn the art

of skillful compromise." (She learned, however, that at times compromise was not enough: One major donor

withdrew upon learning that the new galleries would displace the Damascus Room from the front of the exhibit hall.)

The final consensus was, however, that the times were ripe for change. The old Islamic Galleries had been

designed in the early 1970's, and they had become too small for a growing collection. They were particularly

limited in the way they could showcase carpets and textiles, and it was in this regard that in 2007 I received

a call from Stefano Carboni, then the department's managing curator, who asked if I might know a student or a

protégé—"a junior Walter Denny," he put it—who might be available to help. After some thought, I

had to respond that, to my knowledge, the only Walter Denny with the combination of expertise he sought was

the original, 65-year-old one. And so it was that I committed myself, without knowing quite what I was in for,

to a weekly five-hours-each-way commute from Amherst to spend one seven-hour day a week at the Met. Quickly,

Carboni, Haidar and the superb Met staff melted all of my misgivings. I realized I had made the best decision

in my professional lifetime.

|

|

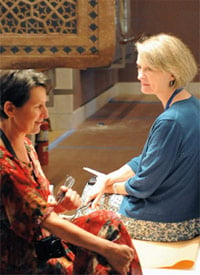

Opportunity for "creative curating" brought Sheila Canby, right, to head the Met's Islamic

Department. She is talking with Florica Zaharia, left, head of textile conservation at the museum. |

ne of the challenges for which my advice was sought lay in Gallery 10, where the 10-by-9-meter (33' x 28')

Spanish Ceiling was to hang: That gallery would also be the major showcase for the Met's collection of almost

800 Islamic carpets. But the ceiling left the gallery's walls too short to hang more than small rugs, and

while the floor was expansive, how could we illuminate carpets on it without the ceiling-mounted spotlights

normally used in museums? I soon learned that this challenge was modest compared to the fundamental one facing

the proposed Moroccan courtyard: Since such a space would be a new construction in an old style, did it

legitimately belong in a museum devoted to art from earlier times? And if so, who would construct it, and

where? In Morocco, and then ship it in pieces? Or build it right there, in the museum?

And then there was all the work going on deeper behind the scenes. The museum had to re-survey its entire

Islamic-lands collection, which had grown much recently—had to re-photograph it, generate digital

records, determine which objects would be displayed in which new galleries and on what kinds of stands and

cases—and take into account as well the rotations, planned years in advance, that would keep individual light-sensitive objects from being exposed too long. To prepare for construction, the old galleries had been stripped to bare

brick. To move debris out and new materials in, the museum had secured approval from the city's Landmarks

Commission to punch a hole in the great Beaux-Arts façade, raise scaffolding and install a temporary exterior

elevator on Fifth Avenue. There were architectural drawings, and there was, over all of it, the whopping price

tag for both the construction and the scholarship that the renovation required. Like champion hot-dog-eaters,

art museums have seemingly insatiable capacities to devour money, and in this, as in so much else, the Met is

second to none.

My place, it turned out, was amid an ever-shifting team of more than three dozen art historians and scholars

from around the world whom Carboni, Haidar and Chief Curator Michael Barry convened to research the collections,

write labels and explanations and prepare a monumental commemorative catalog. As a result, the Islamic Department

was packed tighter than downtown Cairo with some of the world's brightest young experts, and their cramped work

stations, surrounded by piles of books, made it all look much like an updated vision of a medieval scriptorium.

Throughout the process, Mimi Lukens Swietochowski, who had helped lead the building of the 1970's galleries,

stood out as a priceless resource and guide, working closely with Haidar and all the staff during the entire

project. Tragically, she succumbed to leukemia in September, less than two months before the opening.

In one way, the massive effort behind the new galleries seemed to resemble a pyramid balanced on its

tip: After all the experts and specialists have weighed in, the actual work of putting art physically

in place is done by only three people: Collections Manager Annick Des Roches and art handlers Tim Caster

and Kent Hendrickson. Every object moved, stored, crated, uncrated or repositioned—in the right

sequence, at the right time—depends on their skill and, not infrequently, their physical strength.

With the teams in place, and a schedule aiming at a late-2011 opening, hundreds of decisions, small

and large, awaited us. Like a group comprised of both expert and novice skydivers, it seemed that

everyone took a deep breath, and leaped.

|

|

Inch by inch, panels of the Spanish ceiling were raised into position.

|

Re-hanging the Spanish Ceiling

Mecka Baumeister is the Met's conservator for objects (as distinct from paintings, works on paper or

textiles). An exemplar of no-nonsense German expertise, often dressed in her famously flamboyant trousers,

her particular specialty is architectural orphans. The wooden Spanish Ceiling, a carved masterpiece of

geometric strap-work, gilded and elaborately painted, came to the us in 1931 when William Randolph Hearst

bought it from an art dealer. Hearst never installed it, and it was donated to the Met in 1956. Its

origins have so far eluded scholars, but its style resembles some works found in the Castile-Leon region,

and it was probably built between the 14th and 16th centuries by Muslim craftsmen for a Christian

client—possibly a monastery. When it was dismantled from its original gallery at the Met in 2004,

Baumeister and other specialists gradually discovered that it had been enlarged by as much as 60 percent

from its original size and otherwise extensively fiddled with—but by whom, where and when remain

one of the Museum's mysteries.

We had to clean up an historical mess, and yet give the overall impression that nothing had changed,"

says Baumeister. Dismantled, the heavy pieces of the ceiling were stacked around a temporary conservation

laboratory in one of the gutted former galleries, where she and her team studied and conserved the

literally tons of wood.

|

|

|

Crouching on the catwalks that wind among the Spanish Ceiling's hangers, one pair of technicians,

top, winch up the ceiling's central ornament while another pair, above, guide it into its final position.

|

Meanwhile, in Gallery 10, steelworkers constructed a massive, shell-like frame from which the Spanish

Ceiling could hang anew. Renfro Associates, the Museum's lighting consultants, helped us develop fiber

-optic wands projecting from the walls and concealed in the railings around the carpets on the floor.

Those railings would surround the floor-display carpets, and there, the idea of a marble platform on

which to show the largest carpets was scrapped in favor of a modular wooden platform that could be

adapted to various lengths and widths as different carpets rotated through the gallery.

Once Baumeister's team finished, it was then up to Jim Boorstein's five-person crew to hang the

ceiling. Boorstein runs Traditional Line, which specializes in period rooms for museums and other

institutions. The installations at the Met, he says, are "not really a story, but the better part

of a novella." Using hand-operated winches, his crew meticulously lifted each of the ceiling's 21

main trapezoidal sections a centimeter at a time. Once they were in place, they bolted the ceiling's

joists to U-shaped hangers on thick steel rods that hung from the support frame. To accomplish this,

they had to crawl through a trapdoor built into an office above the room, climb down and then crawl

along the shell's narrow, fiberglass catwalks.

As a curatorial decision, filling the gallery with a star-studded geometric ceiling above and geometric

carpets below seems, to the experts, like a great one. Will the public like it? We'll find out in November.

|

|

Its panels of Persian verse now set in proper sequence, the Damascus Room was pieced

together on a steel cage frame.

|

The Damascus Room

Since its installation near the front of the Ettinghausen galleries, the Damascus Room has been one

of the best-known, most-visited parts of the Islamic collection. A gift to the museum from New York's

Kevorkian Foundation, it, too, came from an art dealer who acquired it, no doubt at considerable physical

effort, from an original location thought to have been in the Nuraldin neighborhood of Damascus—but

which, like the home of the Spanish Ceiling, remains unknown despite efforts to learn its precise source.

Extensively decorated in the style fashionable in Ottoman Syria in the early 18th century, the room

consists of a two-level marble floor, the lower level adorned with a playing fountain and the upper

rimmed by low, sofa-like diwan seating. The walls are decorated with paintings of flowers and

a long poem in Persian, and the ceiling is elaborately carved and delicately gilded. During its time

in the dealer's storeroom, tobacco heiress Doris Duke bought two of its wall panels, which she installed

in Shangri-La, her Orientalist mansion in Hawaii, and today, the Met uses photographs to take their place.

|

|

Assistant Curator Navina Haidar in the fully assembled Damascus Room.

|

The Damascus Room's dismantled pieces were arranged in another gutted gallery made into a temporary lab.

There they received the attentions of Baumeister's conservators. The wood panels, covered with fragile

layers of gesso, glue and paint, each had to be cleaned and stabilized. Abdullah Gouchani, the Museum's

epigraphic consultant from Tehran, helped to solve what proved to be a giant jigsaw puzzle, reassembling

the rhymed Persian couplets in their proper sequence. Renfro provided an improved illusion of daylight

coming in the windows by using new led panels. Just before reassembly,

the conservation and design team flew to Damascus and spent several weeks studying the interiors of

18th-century houses still standing in old neighborhoods of the city.

Once the design decisions were made, again it was Boorstein who took over installation. A steel

exoskeleton behind the Damascus Room's walls would provide anchor points, support, and "backstage"

stairs and catwalks for ongoing maintenance and lighting. (The next time a hurricane or earthquake

hits New York, the safest place in the city might be the Damascus Room.) Bit by careful bit, using

|

|

To clean and restore the many pieces of both the Damascus Room and the Spanish Ceiling,

the Met gave over nearby galleries to serve as temporary conservation labs.

|

hydraulic lifts, Boorstein's crew raised each precious piece of 18th-century wood and poetic wisdom

into place. When they were done, others laid the under-floor electrical wiring and the plumbing for

the fountain. And at the entrance, video screens and signage were designed to be useful but unobtrusive.

By mid-summer, all that was left was for Des Roches, Caster and Hendrickson to arrange the items of

period-appropriate decorative art on the room's walls and shelves.

The Moroccan Courtyard

The courtyard was the last of the three major projects in the new galleries. In April 2009, Haidar and her colleagues

made a trip to Morocco, which for the past few decades has enjoyed something of a renaissance in the traditional arts

of woodcarving, marquetry, tile-mosaic and carved stucco. This has been encouraged by, on the one hand, laws that require public parts of buildings to include traditional arts, and, on the other, the deep roots that craft traditions still

enjoy within the country's economy and culture. There, the Met team interviewed companies specializing in historic

restoration and traditional architecture. They chose Moresque, a firm from Fez run by three brothers of the Naji family.

|

|

|

|

The Moroccan Courtyard is designed to highlight the traditional arts of zillij (tile mosaic),

plaster carving and woodworking. The craft team from Moresque assembled the zillij, above left, and

carved the plaster, above right.

|

One of the Najis, Adil, is a slight man who bubbles over with the energy of a Moroccan fountain. Given

to big smiles and even bigger hugs, he is the perfect extrovert, a logical front man for his firm. By

December 2010, he and the first of 10 other craftsmen had arrived in New York and settled into two

condominiums in Queens that Adil persuaded the Arab owner to rent out for the greater good of Arab-American

relations.

With them also came stuff—all heavy, tons of it. There were bags and bags of tiny monochrome-glazed

tiles, cut into stars and triangles, angled strapwork and polyhedral darts, wedges and lozenges: Known

as zillij, these mosaic pieces would be arranged into colorful geometric panels to adorn the

base of the courtyard's walls. There were sacks and sacks of powdery, straw-colored gypsum that, mixed

with water, would coat the upper parts of the walls and be carved into intricate reliefs. There were

paper stencils, hand chisels of all sizes—and a portable cd player

for Moroccan music.

Certainly the Metropolitan Museum of Art had not seen anything quite like Adil's team in decades,

if ever. For once, the art on display was being made before the eyes of its curators: First the

artisans arranged hundreds of zillij face-down on templates, then they poured grout over their backs

to form solid, rectangular sheets that could be lifted and fixed to the walls, glazed side out. Next

came the stucco—a traditional form of carved plaster. They sifted the dry plaster by hand and

mixed it with water in shallow troughs, again by hand. Gobs of soggy plaster were passed hand to

hand and smeared and smoothed on the walls—by hand. By evening, walls and workers often seemed

equally coated.

But the most amazing part was only about to begin. Using paper stencils as fine as lace, they marked

patterns on the dried plaster. Adil's artisans then donned traditional Moroccan jellabas and

stepped into pointy-toed yellow Moroccan slippers—Adil insisted this was traditional for doing

carving work, not just for show—then picked up small steel chisels, much like ones that would

have been used in the 1300's, and began to carve: tap, tap, scrape; tap, tap, tap, scrape—each

move practiced and precise.

|

|

In the museum, the doors, ceiling joists and window lattice (mashrabiyya), were made in Fez.

|

One of the hallmarks of Islamic art is the way it seems to almost alchemically transmute the most

humble, elemental materials—clay and gypsum from earth, wool from sheep, wood and base metals

such as copper and brass—into patterned works of meditative beauty and awe-inspiring complexity.

Watching a dozen virtuosos of stucco-carving bring forth such reliefs of geometry and vegetation is

an unforgettable experience for those fortunate enough to witness it. Adil, his brothers Muhammad and

Hicham and the rest of the crew may have been learning to be New Yorkers by night—they had adapted

quickly to their commute on the New York subway—but in the daytime, the 14th century lived again

on Fifth Avenue.

There were other Moresque artisans at work, too, back in Fez, carving wood, the third major aspect

of traditional Moroccan architectural ornament. There were cedar beams, lathe-turned wooden dowels

assembled into screens (mashrabiyya), and carved doors. The New York crew installed these,

and in the square opening at the top of the court, more led lighting

simulated Moroccan daylight. As a final touch, under the watchful eye of Nadia Erzini, the museum's

consultant on Moroccan decoration, conservators treated the wood to give it the dark patina of 700

years of oxidation.

To Adil, the pride taken by his craftsmen is now all the greater for their sense of having brought

their traditions successfully to one the most prestigious art museums in North America. "We brought

two very beautiful things to New York," he says. "Our craftsmanship itself, and the results of that

craftsmanship that we will leave behind."

But Haidar believes that they brought more than this. "The Moroccans were like a breath of fresh

air in the galleries," she says, pointing out that they transformed the way the staff worked as

much as they transformed gypsum. The museum staff often brought the artisans cookies and refreshments,

and in the camaraderie soon many of us at the museum were hugging each other just like Adil.

n late 2009, as the renovation work was beginning to show signs of fruition, Museum Director

Thomas Campbell made an offer to Sheila Canby, who since 1991 had been Curator of Islamic Art

and Antiquities at the British Museum. Sensing a new opportunity for what she calls "creative

curating," she accepted, and came to New York as Curator of Islamic Art. "In a sense, I've been

preparing for this job all my career," she says. "Thanks to the way the teams functioned, I was

able to join in the work on the new galleries in a seamless way."

By September, not far from Canby's office on the museum's third-floor mezzanine, plans were

under way for November's opening festivities, the vip and press

previews, and visits from sundry consuls, ambassadors, patrons, princes and presidents. Last-minute

work on labels, wall texts, videos, educational programs and the catalog continued at fever pitch.

Team spirit was much in evidence.

When the doors open, says Haidar, she hopes visitors will find that "we've presented the

Islamic world and Islamic art as the confident equal of any of the world's great artistic

traditions." With that, she believes, will come better understanding that "Muslims are like

everyone else—we all love beauty and beautiful things, and appreciate the enrichment

that beauty brings to everyday life. We want to share that common humanity in the new galleries."

As for herself, she plans to "get back into my scholarly work on Indian painting, and to

rediscover myself as a scholar. In the long term, my dream is to return to my native India,

where I hope I can someday make a significant contribution in the museum field using the

skills I have acquired here."

As I reflected on her comment, I saw again how the Met's spectacular renovation is but one

large step in what is today an entirely global process, one that continues in Paris, Toronto,

Doha, Abu Dhabi and other cities around the world. In their own ways, museums are a lot like

Adil and his artisans: continually bringing into relief patterns and beauty, sharing insight

and discovery, whether it's one chisel-tap a time, one gallery at a time or one museum at a time.

|

Walter B. Denny (wbdenny@arthist.umass.edu)

teaches art history at the University of Massachusetts/Amherst

and serves, one day a week, as Senior Consultant in Islamic Art at the Metropolitan Museum of

Art. He writes extensively on the art of Ottoman Turkey, and has photographed the Middle East

since he was 15. |