|

| Arthur Clark

|

|

|

| andrea avezzù

|

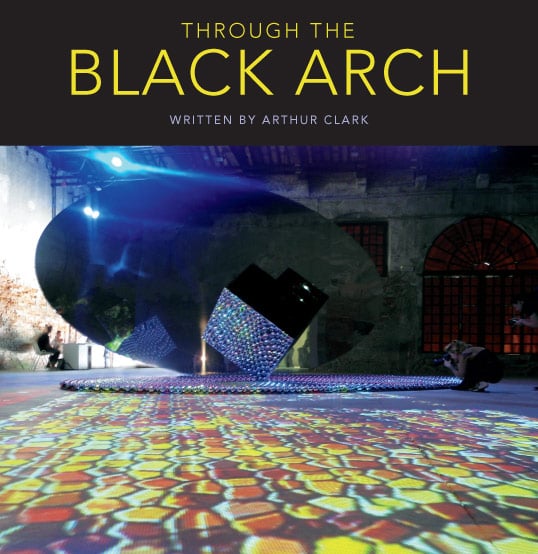

One room's exhibit in the Arsenale didn't look like much at first. From the door, all that

appeared of the installation titled "The Black Arch" was a flat, solid black ellipse some

seven meters (23') long, nearly blocking the path in. But slipping out from around its lower

curves were glimmers of light and color from images projected onto the floor. And, in the

distance, murmurs of voices in Italian and Arabic stimulated the viewer's curiosity to find

out what lay on the other side.

There, the view transformed: The black ellipse became a mirror of stainless steel; on the

floor in front of it stretched a pool-like array of 3257 polished silver spheres, each the

size of a grapefruit, arranged in curves that echoed the ellipse. In the pool of spheres,

toward its left side, a mirrored cube, balanced on a corner, stood about shoulder-high. Its

lower sides reflected the spheres; cut into its top corner was a cubical niche that held a

few handfuls of pebbles. The sounds of Italian and Arabic voices were louder on this side,

and the images on the floor proved to be colorful fragments of Renaissance mosaics and views

of pilgrims at prayer in Makkah.

"It's very sensitive," said visitor Eric Guérin of Joinville, France. "There are so many

things that tease my eyes and my ears. It's like a seashell that opens and lets you in."

"The Black Arch" was created for the Biennale by artists Shadia and Raja Alem, sisters born in

Makkah, Saudi Arabia. It marked the first-ever exhibit by Saudi Arabia at the show, whose 2011

theme was "ILLUMInations"—art as a way of deepening human connections across boundaries

and borders of all kinds.

"Only when you go round the back of [the ellipse] do you become aware of its other face...in which

your own milky reflection mingles with ghostly photographic projections of pilgrims praying in Makkah

and Arab merchants taken from Venetian paintings," The Financial Times reported, calling the

Saudi presentation "a ground-breaking move." The Alem sisters, who divide their time between Saudi

Arabia and a shared flat in Paris, agree. "The kingdom joining the Venice Biennale with the work of

two women is breaking the wall between us and the rest of the world," says Raja. "It is a revolution

in itself," adds Shadia.

The sisters are independently successful: Raja is an acclaimed writer whose novel The Dove's Necklace

won this year's International Prize for Arabic Fiction; Shadia is a visual artist whose work has been

widely exhibited internationally. From time to time, the sisters join forces, and at the 2009 Biennale,

their joint work was part of a private Saudi group exhibit called "Edge of Arabia."

"The Black Arch" marks their most high-profile collaboration so far. Cinzia De Bei, who holds an art

degree from Venice's Ca' Foscari University and who helped staff the Saudi Pavilion, observed that

while casual visitors tended to be "really amazed" at the Alem's installation, those who lingered were

"even more amazed at the work. It's not just beautiful. They see it also has a deeper meaning."

|

|

arthur clark

|

The project began, explains Shadia, when the Saudi Pavilion's co-curators, Mona Khazindar, director of

the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and Robin Start, a London-based art consultant, named Shadia among

six Saudi artists to compete for the honor of producing the kingdom's exhibit at the 2011 Biennale.

Shadia at once spoke to Raja, and together with four other artists the Alems visited the Arsenale room

assigned to the Saudi exhibit: 350 square meters (3770 sq ft) of emptiness; a high, beamed ceiling; worn,

burnt-orange brick walls; five windows, all on one side. "The space was horrible," Shadia remembers.

"We thought, 'What can we do with that?'"

As they were leaving Venice, awaiting their flight at Marco Polo Airport, they struggled to find a way

"to conquer this space." It was, Shadia recalls, only when their flight was delayed that the sisters found

what proved to be the key, right at their fingertips: There were powerful links among the 13th-century

Venetian after whom the airport was named, their own childhood in the holy city of Makkah and the Biennale itself.

It was, says Raja, "this act of traveling, what Marco Polo represents," combined with

the realization that it was also, at that moment, the Hajj season, when Muslims come to Makkah

from around the world—often after long waits in airports. This, they also realized, spoke to the

theme ILLUMInations: travel—both physical and symbolic—is both a means of communication

and a deeply shared human experience.

They quickly also invoked the name of Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan from Tangiers who set out on travels to Makkah and

on to India, China and more in 1323, the year before Marco Polo died. The two never crossed paths, says Raja, but

they shared the calling of travelers.

The sisters, too, have journeyed as children and adults, and "the act of traveling has made a

difference in our lives," says Raja. She explains that, when she was a child, every year at the

time of Hajj her family turned the lower floors of their seven-story home over to pilgrims. The

Alems moved upstairs, affording the sisters, who were born just more than a year apart, almost

literally a bird's-eye view of the kaleidoscope of cultures that gathered in the city.

They also recalled a particularly memorable story from their paternal grandmother. There once was

a queen, says Shadia, who as a bride in her husband's many-roomed palace, was told "she could open

any door except the black door." Eventually, of course, she

did open the black door—and discovered a new world.

"Black is like prohibition to cross over something. So it is a challenge," says Raja. "If you allow

that black to prevail," you are left without knowledge, and "it creates war and [other] problems."

Often, the metaphorical "crossing" is less difficult than one fears it will be, she continues,

"like 'The Black Arch,' where one face is black and the other face is reflective and full of light.

Between them is only a very thin barrier."

|

|

andrea avezzù

|

|

In cube's niche sits a mix of pebbles from Venice, shaped by the sea, and from Muzdalifah in Makkah,

shaped "by people's hands, sweat and desire over centuries."

|

They further experienced the mystery associated with black, Raja says, in the kiswah that

is draped over the Ka'bah in the Great Mosque in Makkah, where they attended prayers every Friday

with their mother. "When we look at the Ka'bah covered in black," she says, "there is something

unimaginable behind it."

A few weeks after their visit, the sisters had sketched what became "The Black Arch." Fuad Therman,

director of Saudi Aramco's King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture and a member of the Saudi

selection committee, said the committee "appreciated the emotional depth and visual strength" of

the Alems' proposal.

The sisters worked with fabricators in France to construct the installation, and Shadia herself

took photographs and recorded evocative sounds from Makkah and Venice. Her images of mosaics from

St. Mark's Basilica and other buildings in Venice show links with the Middle East as well with the

city's local religious history. Her photographs from Makkah portray the textures of that city,

mainly through mosaic-like images of pilgrims. Her soundtrack is as varied as the adhan,

the call to prayer, in Makkah, the noises of a marketplace and a wedding, and, from Venice, the

song of a gondolier, the chatter of a crowd in St. Mark's Square—and an announcement of a

flight at Marco Polo Airport, much like the one that triggered the project's conception.

They also realized that water was an element that both linked and distinguished the two cities:

While Venice and Makkah share a history of maritime travel (Venice directly and Makkah by way of

nearby ports), Venice is built in the sea and endures the historic threat of floods, while Makkah

is built in the desert and endures the historic threat of droughts. Between the 10-minute projections

of images from each place, the sisters created an interlude in which abstract images of waves

rippled along the floor to the sounds of lapping water and seagulls.

A further metaphor lies with the pebbles held in the niche at the top of the cube. Some of the

pebbles Shadia gathered from Muzdalifah, where pilgrims ritually throw small stones at pillars

representing the devil, or, as Raja puts it, "visualizing a negative moment in your life and

aiming a stone at it." She calls the pebbles "miniature sculptures shaped by people's hands,

sweat and desire over centuries." Mixed in with those pebbles are others from Venice.

|

|

blaise adilon

|

|

Co-creators of "The Black Arch," sisters Raja and Shadia Alem (left and right) called it

"a remix or a dialogue of sounds and light, woven of the two cities' mosaics and ornaments."

|

While rich in symbolism, the Alems insist that "The Black Arch" is "not specific to any single

place, culture or time," and that it is open to personal interpretation. For example, says Shadia,

the cube, "may represent the Ka'bah" at the center of the Great Mosque, and the spheres may represent

pilgrims, but the cube could no less effectively represent "your city" and the spheres, reflecting

the visitors themselves, literally show "people everywhere." The importance, the sisters explain,

lies in the mixing and sharing that is continuous, and of which the viewer is a part.

Co-curator Mona Khazindar agrees, saying "The Black Arch" makes a lasting impression.

Many visitors "were taken by surprise," she notes. "They were not expecting to see such artwork

from Saudi Arabia and from Saudi women.... I think it has changed the perception of Saudi art in

the West.

"It's a very cosmopolitan artwork. It's about exchange—learning from the Other, enriching

the Other and being enriched by the Other. It's enlightenment! Such artworks are very important

because they teach you to look at the Other through a

different window."

Saudis, too, have been surprised.

"Within Saudi Arabia, you have lots of artworks that tackle more traditional or local themes.

'The Black Arch' is very conceptual, very modern and very poetic," Khazindar says. "We never

thought of Makkah as having any resemblance to Venice, yet it does. Makkah is also a mosaic

of people, of culture and colors."

Shadia and Raja hope "The Black Arch" can tour other cities. Then, they say, even more people

might find themselves only "a black door" apart from each other—and be able to step through to meet.

|

Arthur Clark (arthur.clark@aramcoservices.com) is assistant editor of Saudi Aramco World

and editor of Al-Ayyam Al-Jamilah, the semiannual magazine for Saudi Aramco retirees.

He lives outside Houston. |