|

|

| Written and photographed by John Feeney |

|

|

|

| Often inconspicuous amid Cairo’s bustle, the entrances to the city’s few remaining baths are often as ornate as those of comparably sized mosques. Left to right: The Hammam al-Sultan Inal, built in 1456, opens off the old Qasaba, the first main street of Cairo. The Hammam Sinan Pasha, in the Nile-side neighborhood of Bulaq, dates from 16th-century Ottoman times. The colorfully decorated Hammam El-Doud was built in the 13th century, rebuilt in the 19th and damaged by earthquakes in recent years. The hammam attached to the Sultan Qala’un mosque also dates from the 13th century. |

|

|

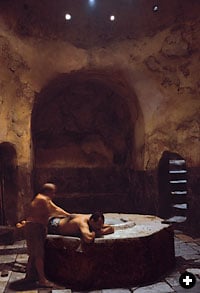

| The square plunging pool at the 18th-century Hammam al-Tanbali. |

hat watery glory it all was: To be steamed, scrubbed, rinsed and scented according to medieval Cairo’s public-bathhouse ritual was to be cleansed like nowhere else on earth—or at least nowhere outside the former boundaries of the Ottoman Empire. Much of this ritual has long since evaporated with the vanishing of the bathhouses, called hammams in Arabic. In fact, two eminent scholars of the Middle Ages declared to me recently that the old hammams were entirely gone—extinct as the dodo. Well, I have news for them.

hat watery glory it all was: To be steamed, scrubbed, rinsed and scented according to medieval Cairo’s public-bathhouse ritual was to be cleansed like nowhere else on earth—or at least nowhere outside the former boundaries of the Ottoman Empire. Much of this ritual has long since evaporated with the vanishing of the bathhouses, called hammams in Arabic. In fact, two eminent scholars of the Middle Ages declared to me recently that the old hammams were entirely gone—extinct as the dodo. Well, I have news for them.

There are still in Cairo half a dozen traditional hammams that have been busy washing bodies for centuries, places where you can still today have your joints cracked, your ears twisted (no damage, mind you) and your skin lathered up in the old manner.

Five hundred years ago, in the days of the ruling Mamluks, there were more than 300 hammams in Cairo, “one for every day of the year,” as a modern hammam owner puts it. These were spread throughout the districts of what was one of the world’s largest cities. During the 14th and 15th centuries, with a population fluctuating at around half a million, Cairo was larger by far than London, Paris or Rome. European travelers coming to Egypt in those times were inevitably amazed at the predilection of the people for washing—some saw it as an obsession, for in Europe too much washing was frowned upon. But Egyptians were a river people, and this habit was as old as Egypt itself. In the mid-19th century, Edward Lane noted in his classic Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians:

|

|

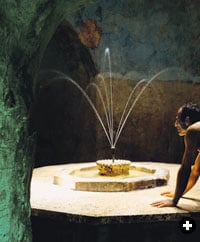

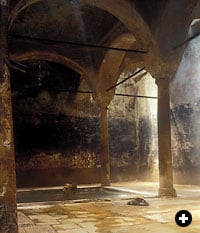

The hararah chamber, with a hot fountain such as this one at Hammam al-Tanbali, is typically

the steamy heart of a Cairo hammam. |

|

|

| Above: Colored glass set in a hammam’s vaulted ceiling. Below: Floor plan of a Cairo hammam, after Edward Lane. A: entrance; B: meslakh, or reception and retiring room; C: mallim’s station; D: cold fountain; E: coffee stall; F: toilet; G: first steam room; H: hararah, or central steam room; I: faskeeyah, or hot fountain; J: maghtas, or plunging pool; K: boiler room. |

|

|

|

Bathing is one of the greatest luxuries enjoyed by the people of Egypt. The inhabitants of the villages of this country, and those who cannot afford the trifling expense incurred in the public baths, often bathe in the Nile.

This may have been tradition, but it happened to dovetail with religion. In Islam, cleanliness is paramount, not only for the soul, but also for the body. According to Islamic law, the ritual washing of face, hands, ears and feet must be performed before each of the five daily prayers. So it was that the first of Cairo’s hammams were attached to mosques. With large supplies of water always on hand for the washing of the faithful’s hands and feet, it was but a short step for a mosque to also provide supporting services, from a full-scale hammam to a modest sabil, a fountain of free drinking water. The latter was a particularly welcome gift in a desert city where water had to be laboriously hauled daily from the Nile—and paid for.

But a hammam could just as well function independently of a mosque. Some public hammams were attached to local markets. Some were for men only; others were for women and children only. Many others were reserved for men during the morning hours, when they would be run by male attendants, and reserved for women and children in the afternoons, with a change to female staff. To this day a bath towel, or any piece of linen, hung across a hammam’s entrance is a centuries-old signal that it is the time of day for women.

Consequently, Cairo’s hammams became community focal points, often playing a role in all the main events of a person’s life, from youth to old age. For the elaborate ceremonial washing of a bride, Lane wrote that hammams were often rented by the two families, and the women of the families would gather with their guests:

There are few pleasures in which the women of Egypt delight so much as a visit to the bath, where they not infrequently have entertainments and often on these occasions, they are not a little noisy in their mirth. They avail themselves of the opportunity to display their jewels and their finest clothes and to enter into familiar conversation with those whom they meet there.

A bridal ceremony, Lane wrote, began with a procession from the house of the bride to the hammam. Seated under a gilded canopy, she was carried through the narrow streets escorted by family and friends, led by musicians, drummers and dancers. Likewise, the groom and his friends made a more subdued visit to their hammam. Today, according to Muham-mad Mustafa Hegaze, chief masseur at the Al-Malatyali Hammam, bridegrooms come to the hammam, if they come at all, with only one best friend.

Another visit to the hammam was expected of mothers-to-be, and another visit took place 40 days after giving birth. A boy’s circumcision procession through the streets always went first to the local hammam. A ritual washing also took place after an illness. To this day, Cairo’s few remaining hammam owners adamantly claim, often in so many words, that “the hammam is a good doctor, and its soothing waters banish all anxieties.”

On feast days a hammam could be rented for private parties. Thus on one occasion or another, it was not unusual to hear singing, drumming and clapping from within the walls of a hammam. Luxurious private hammams in palaces and in the houses of rich merchants might be paved with mosaic marble patterns and roofed with fantastical sunlit glass ceilings, making settings for even more elaborate parties.

With such joyous goings-on taking place amid the steam clouds, what outsider might not wonder if the hammam were some kind of madhouse? What is it indeed that makes humans react so in the presence of water? Certainly to swim and splash about in a summer sea, or a river, can cause reckless delight in people of all ages. So to hear singing and clapping from the hammam was perhaps not so outlandish. Is there not a natural inclination for some people to burst into spontaneous song under the shower? Even a canary sings when it hears the tap running.

Socially, what better place was there, immersed in the soothing, steaming waters, to discuss the latest scandal or to hatch intrigues? And for women especially, it was a place to see and be seen: Matchmakers were often on hand.

Together with mosques, hammams were thus vital social centers. Each district’s hammam was usually named after the locality where it was situated. For example, the Nah-haseen hammam, the “coppersmiths’ hammam,” was located near that trade’s section of the bazaar. The hammam of Sultan Qala’un was next door to his 13th-century mosque and his famous hospital, which in its day was considered one of the wonders of the world for its free treatment of 4000 patients a day. The hospital is now a ruin, but a bathhouse still functions on the same site, though more in decrepitude than splendor.

|

|

| Top: Mukeyyisate (masseur) Muhammad Mustafa Hegaze rubs down a customer at the Al-Malatyali Hammam. The cost of a visit to a traditional Cairo hammam is often five to 10 Egyptian pounds, or about $1.25 to $2.50. Below: During its more than 500 years of operation, the level of the streets around the elaborately decorated entrance of the Hammam Bashtak has risen by more than two meters. |

|

|

Not far away, in the street of the Suq al-Silah (Armorers’ Market), where Mamluk soldiers purchased swords, daggers, shields and helmets, there was—and still is—the hammam built by a Mamluk amir. He commissioned it in ad 1322, and its marble façade is as ornate and grand as the entrance to a mosque. The beautifully carved inscription over the entrance reads: “His Most Noble and High Excellency, our Lord, the Great Amir Sayf al-Din Bashtak of al-Malik al-Nasir ordered this blessed bath built. May his glory last for ever.”

The glory of Sayf al-Din’s hammam, at least, has indeed lasted for more than six centuries. The external façade is in an excellent state, though the interior is very dilapidated. It is still used by women of the district living in surrounding apartments. The traditional towel hung across the hammam’s entrance indicates men are not to enter.

Not far away on Muhammad Ali street, which leads to Saladin’s 12th-century citadel overlooking Cairo, is the Hammam El-Doud, still showing its bright colors, though alas now ruined in the earthquake of 1972. But the Hammam al-Matili, which has been washing bodies for nearly five centuries, and the Al-Tanbali Hammam still do a brisk business. Tanbali is open for men on Friday and Sunday and for women on other days. Thursdays and Fridays, in medieval times, were the favorite days for visiting the hammam, the former to make ready for Friday prayers at the mosque and the latter to spruce up for a day of visiting friends and relations.

The most elaborate surviving hammam is that of Muhammad Ali, who ruled Egypt between 1805 and 1849. In an excellent state of preservation, but neither open to the public nor in use within the walls of the citadel, its two-meter-deep (6 11/42') plunging pool is set beneath a scintillating canopy of glowing, sunlit green and pale-yellow glass skylight panels. Set into the wall is what must be the largest and most exquisite soap and sponge holder in the world, veiled by a curtain of marble carved in hanging folds.

Though the floor plan of each hammam was unique to its size and location, hammams all had their common points. Built of brick covered in plaster, the windowless walls were always far thicker than mere structure required, so as to keep in the heat. For the same reason, the entrance was always small and narrow—yet it was also usually imposingly framed and painted in bright colors, perhaps to signal the relief that could be found within. Some likened the “delights of the waters” to Paradise itself. But even in this urban paradise, danger lurked: Folklore held that the damp, dimly lit passageways were possible abodes for jinn, or spirits of unreliable intentions. It was therefore considered wise to say a brief prayer before stepping into the hammam’s water—left foot first, according to custom, “lest you slip.”

The actual washing of the body, according to established hammam custom, was a most vigorous affair. “The exertions of the bath” were not to be taken lightly. If you were a man of medieval times setting out on foot for your favorite hammam, you would have joined the commotion of the narrow Qasaba, the main street filled with choruses of bells on the harnesses of passing horses and donkeys, the clashing brass saucers and the shouts of sellers of iced drinks, and the warnings and cracking whips of cart drivers. You would pass lines of haughty camels bearing dripping oxskins of Nile water that replenished the underground cisterns of mosques, sabils, and hammams. You might also pass someone picking up the camel droppings, which, along with the city’s refuse, provided the fuel to heat, among other things, the water in the hammams.

Arriving at the hammam’s entrance, you passed into a quiet, steam-filled world. Down a narrow passageway (not without some trepidation if this was your first visit), you came into the meslakh (“reception room”), with its central, often octagonal fountain of cold water, in contrast to the hot to come. Everything about the hammam’s internal operation was efficient. The mallim was the man in charge. The Master of the Furnace, assisted by his wakked, or stoker, kept the hammam’s fires blazing and the cauldrons of water bubbling. In spite of—or perhaps because of—his euphemistic title, the “Superintendent of Dung Fuel” was looked down upon. Masseurs were designated by order of seniority. But before a masseur could get to work on you, the undressing procedure had to take place. As Lane described it in the mid-19th century:

On entering, if he has a watch and a purse containing more than a trifling sum of money, he gives these to the mallim who locks them in a chest. His pipe and sword he commits to a servant-of-the-bath who takes off his shoes and supplies him with a pair of wooden clogs, the pavement being wet.

Divested of all you stood up in, wrapped from head to foot in towels and turban, you went clattering off over the slick marble floor, passing through a series of small rooms, each hotter than the one before, where little jets of gurgling hot water induce the profuse sweating required before the hammam ritual can begin in earnest.

|

|

| Top: Illumination in hammams originally came exclusively from small skylights set in the buildings’ vaults or domes like constellations in the dome of the night sky. Below: Towels hung before a hammam’s entrance are the traditional sign indicating that the hammam is open to women only. |

|

|

As the heat becomes progressively more intense, servants remove your robes, one by one, until you are left with a loincloth. Opening yet another small door, a servant ushers you into the dim heart of the hammam, the hararah, a steam-filled chamber much hotter than any before. (“How much more of this can I stand?” not a few may have asked.) Overhead, a masonry dome, pierced with small glass openings, admits narrow shafts of sunlight down onto a faskeeyah, or fountain spouting steaming hot water. Laid out on the wide, octagonal marble perimeter of the faskeeyah are your fellow bathers, prostrate, sweating, some worked upon by equally sweaty masseurs. Here, amid the what-have-you of humanity, the masseurs are not above calling out sly asides to each other about the bodies in their grasp.

Emerging silently in his bare feet from a steam cloud and looking like a wrestler, your mukeyyisate—your masseur—advances. “Good heavens, is this man friend or foe?” you may wonder. “What have I let myself in for?”

The mukeyyisate motions for you to lie down on a towel he spreads on the marble platform beneath the steaming fountain. You are now ready to submit to the onomatopoeic first stage of the hammam ritual, the taktakah, the “cracking of joints.” Each limb of your body is wrenched first one way then the other, a process designed to make your joints supple. The pulling and cracking of fingers and arms is followed by similar work on your neck: a twist left (crack), then right (crack), yet done with such great skill that, as Lane wrote, “an accident is never heard of.” Next, your ears are twisted and made, yes, to crack too: You are not the first to wonder that this could be so at all. Your masseur sits you upright, and next jams his knee against your back and pops each vertebra: crack… crack…crack...such alarming sensations! But afterward the thought creeps in: “I’m beginning to enjoy it.”

Another attendant advances and begins to rub the soles of your feet with a kind of rasp called a hager el hammam: “You’ve got to hand it to them, this is certainly thorough.” But the scraping of the soles of the feet may send you into shrieks of laughter, and if you unwittingly kick the mukeyyisate and sprawl him over the wet floor, he is likely to rise, undeterred but perhaps glaring, and grab your feet again until you are properly done.

Then he turns gentler. Using the perfumed white fiber of a palm brought specially for the purpose from the Hijaz, the mukeyyisate starts to lather the flesh and rinse the sea of foam with ladles of hot water, repeatedly thrown.

Twisted, manipulated, washed, rinsed and wrung out to perfection, you are led into the hammam’s last vaporous chamber, the maghtas. A steady stream of hot water pours down from the dome overhead into a deep plunging pool. This is the climax of the hammam’s hidden glory. Remembering to say a quick prayer before you place “your left foot in first, lest you slip,” you sink languidly down to your neck in the steaming tub. Catching your breath and gazing up, through the vapory haze you see the vaulted ceiling’s geometric pattern of colored glass lit by the sun.

|

|

| The plunging pool lies amid the time-worn walls and columns of Hammam al-Tanbali. |

After all the vigor—to put it mildly—of the hammam ritual, to now recline in deep hot water, overlooked by such beauty, is a delight of delights. How could any anxiety fail to vanish? But life must go on. When you emerge, all aglow, a servant of the bath quickly re-swathes you from head to foot in turban and towels. A modicum of decorum having been swiftly restored, you are gently led back to the “retiring room,” placed upon a mattress and cushions amid other swathed figures, and given coffee or fruit juice to sip. Not all of the swathed figures are awake. It’s a good time for a snooze.

Back at the entrance, you receive all you came in with: pipe, sword and what-have-you. Outside paradise, back in the dusty world, you stroll or ride gently home on the back of a donkey—automobiles not yet having been thought of.

Well, that’s how it was done up through about the 1930’s. But how times change! No more is dung fuel used to heat the water. Today, it’s done with electricity or natural gas. No more is Nile water brought to the door of the hammam in dripping oxskins. It’s still Nile water, of course, but it is piped in. In fact, it was the arrival of water piped into every Cairo home in the late 19th century—or at least many of them—that turned bathing into a private, no longer a public, experience, foreshadowing the end of the glory days of the city’s hammams.

Exposed now to centuries of steam and with bathhouses having no appreciable commercial revenues, the walls of the few remaining hammams are faded and cracked, and so far no one has bothered to restore even one for posterity. But Muhammad Mustafa Hegaze, who has been washing bodies for more than half a century and who now works at the Al-Malatyali Hammam, is a skilled, old-school masseur. Like his predecessors, he is ready with a smile and will, at your request, “crack” every bone in your body. To take the full treatment once took about an hour, but even in today’s no-frills world you might still get the most thorough scrubbing-down to be found this side of heaven, all in 30 minutes.

But will you have been “done” to perfection as in days gone by? It’s worth finding out while you still can. But remember to say a small prayer before stepping into the plunging pool, and to go in left foot first, “lest you slip.” The marble pavement is still wet.

|

John Feeney worked in Cairo as a free-lance filmmaker, photographer and writer for more than 30 years and still returns there frequently from his home in New Zealand (NH.Phua@xtra.co.nz). He dedicates this article to the late Prince Hassan Aziz Hassan, “who first took me to Cairo’s few remaining hammams, according to his carefully researched list.” |

|

|