|

|

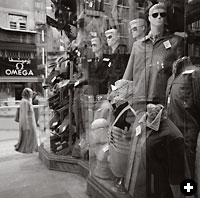

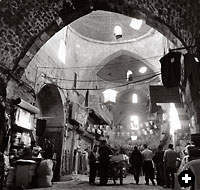

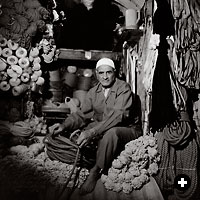

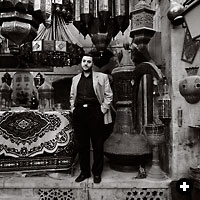

| Though shops in Aleppo’s Aziziyah district, above, and on Sharia Qawatli are more likely to resemble their western counterparts than those in the world’s oldest covered market, below, the suq is no timeless arcade: Fax machines whir, international magazines inspire dress design, and antiquarian bric-a-brac sells to tourists at a good profit. |

|

|

leppo vies with Damascus for the title of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city. Both are mentioned in Eblaite tablets from the third millennium BC, where Aleppo goes by the name Hal-pa-pa, but fine neo-Hittite reliefs recently found in Aleppo’s towering citadel mound may give a slight edge in the antiquity contest to this more northerly of Syria’s two largest cities.

leppo vies with Damascus for the title of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city. Both are mentioned in Eblaite tablets from the third millennium BC, where Aleppo goes by the name Hal-pa-pa, but fine neo-Hittite reliefs recently found in Aleppo’s towering citadel mound may give a slight edge in the antiquity contest to this more northerly of Syria’s two largest cities.

Since those earliest times, the long-distance trade in rare exotics and the face-to-face retailing of everyday essentials have been Aleppo’s sustenance. The clamor and calls emanating today from its suqs (markets) are the echoes of the same sounds that rang there four thousand years ago.

Today, some 15 kilometers (9 mi) of stall-lined streets, alleys and commercial cul-de-sacs wind off the suq’s 1.5-kilometer (1-mi) main thoroughfare, covered in places with stone and brick vaulting. It follows the route of the Decumanus, the city’s main east-west street that was laid out in Hellenic times, in Aleppo as in other cities of the Mediterranean world.

Aleppo in those times was the principal commercial entrepôt between East and West, where the riches of India and Mesopotamia met Mediterranean traders and middlemen who shipped the goods onward to the Greek mainland and, in later years, to Rome.

Starting up near the citadel, the Decumanus runs downhill through secondary suqs devoted to specific crafts or products, such as the Suq al-Attarine, the Perfumers’ Suq. At the bottom end is the dog-legged Antioch Gate, high enough that camels did not even have to duck as they marched out, bound for the port at Antioch, 80 kilometers (50 mi) to the west.

Today, traders new to Aleppo fly in—from Moscow most often—or they come by bus from Turkey. What were once “exotics” have largely given way to global-brand consumer products: The French Nafnaf clothing brand is today as common in the market as no-logo lamp oil once was.

Today, traders new to Aleppo fly in—from Moscow most often—or they come by bus from Turkey. What were once “exotics” have largely given way to global-brand consumer products: The French Nafnaf clothing brand is today as common in the market as no-logo lamp oil once was.

Conversations with Aleppo’s salespeople, recorded here in the old suq and in the city’s urban shopping quarters, capture both what has changed in less than a lifetime and what never seems to vary from one millennium to the next.

Abdel Qadir Na‘aal

Spices, Perfumers’ Suq

ecause I display everything I sell, like this za‘tar pyramid trimmed with red sumac and shaved coconut, I get plenty of tourists asking to take my picture. My family name means ‘farrier,’ but I don’t know to which of my ancestors that name was given. All I know is that my grandfather was a spiceman, named Abdel Qadir like me, and he sold spices in the days of the Ottoman Empire. I remember him selling spices in this very stall when I was small, dressed in Ottoman-style trousers.

ecause I display everything I sell, like this za‘tar pyramid trimmed with red sumac and shaved coconut, I get plenty of tourists asking to take my picture. My family name means ‘farrier,’ but I don’t know to which of my ancestors that name was given. All I know is that my grandfather was a spiceman, named Abdel Qadir like me, and he sold spices in the days of the Ottoman Empire. I remember him selling spices in this very stall when I was small, dressed in Ottoman-style trousers.

“I sell all the usual things you expect to find from a spiceman: cinnamon, sweet and black pepper, coriander, dried ginger; za‘tar [thyme] and cumin, and then there are the more unusual medicinal herbs. In fact, people think I’m a folk doctor. They rely on me to treat things no medical doctor can cure. They want me to give them medicines they’d never find in a clinic, like zayzafoon leaf for a cough, za’roor flowers for heart problems, anise seed for sleeplessness, chamomile for stomach aches, senna for constipation.

“I mill most of the spices in front of my buyers so they will see that what should be bought fresh hasn’t been sitting and drying out on the shelf for ages. A spiceman must have everything in stock, even if it’s rarely requested, and he must carry something to cure everything.

“My most unusual spice is kleejah. It looks like lichen. You use it to make kleejah biscuits. It’s very old-fashioned. Kashshar al-‘ajouz, “old man’s hair,” is something else that is rarely requested, but you can always find it in my stall. Anyway, I have no bugs here that might eat my stocks. With such strong herbs, they’d never last a minute here. Bugs don’t like spices, but people can’t seem to live without them.”

Silva Jezdanian

Clothing, Aziziyah Quarter

ziziyah is Aleppo’s most westernized neighborhood, home of many of the city’s international chain stores. Among them, Kickers is a British casual-clothing brand heavily advertised throughout the Middle East.

ziziyah is Aleppo’s most westernized neighborhood, home of many of the city’s international chain stores. Among them, Kickers is a British casual-clothing brand heavily advertised throughout the Middle East.

“I’ve worked six months at Kickers, but I’ve been selling clothes since I turned 15. I’m a native Aleppine so I know what our people want to wear these days. Even kids have new ideas about fashion. Brands make a big difference to them. Here there are fewer customers than in the suq, but they are willing to pay big markups if they really want a brand name. Still, compared to Lebanon, Syrian markups are nothing. Businessmen come here from Beirut and load up on Nafnaf and Adidas and Polo and go home to make a profit selling piece by piece. Here European-label jeans cost almost half what they cost in Lebanon.

“When small children come in with their mothers and get fussy, I know it’s best to make the baby happy. A happy baby is a quiet baby, and a quiet baby lets mother shop longer and buy more. Thursday and Friday are our busiest days. Since this is a largely Armenian quarter, we are closed Sunday, and Saturday is when everyone does household chores, not go shopping. Shopping for clothes like these is more entertainment than necessity. Everyone likes to shop, but only the rich can buy.”

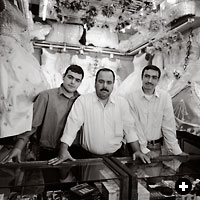

Muhammad Waraaq and sons Fadil and Abdelrahman

Wedding dresses, Handkerchief Suq

ogether with my sons and a brother, we have two stalls across from each other in this suq. It’s called Suq al-Manadil because fancy items were always sold here. My great-great-grandfather was a paper dealer. In the 19th century, he traveled to Austria to buy and sell paper, so that is how we got our family name, Waraaq, which means ‘paper seller.’

ogether with my sons and a brother, we have two stalls across from each other in this suq. It’s called Suq al-Manadil because fancy items were always sold here. My great-great-grandfather was a paper dealer. In the 19th century, he traveled to Austria to buy and sell paper, so that is how we got our family name, Waraaq, which means ‘paper seller.’

“We’ve got 15 boy tailors in our dressmaking shop. My brother Zein is the designer. He learned only through experience, not in school. We change the colors of our engagement dresses every year, because tastes in color change, but never, not ever, for wedding dresses. Brides must always wear white.

“Brides usually come with their whole family, but it’s the father alone who pays! In Syria, we have a tradition that newly married women wear their wedding dresses every Thursday for the first three months. That way my dresses don’t stay in the closet after only one day.

“I don’t care how long a woman takes to decide or how often she changes her mind; what is important is that in the end she buys, because then I have a customer for life. For life, you ask? Yes, because next year she will bring in her friend when it is her turn to marry, and her daughter 20 years later, and maybe even her granddaughter long after that. She will remember me whenever she thinks back on the good years, and think I brought them to her because of the dress she wore on that one day.

“The most trouble is when a bride’s aunt or a sister comes in full of her own opinions. She tries to persuade the bride, and a salesman makes a big mistake if he tries to please the aunt and convince the bride of the aunt’s way of thinking, because the bride will eventually make up her own mind, and it will be something else.

“Some brides can make up their minds in 10 minutes; others stay two hours and still walk out with nothing. I have seen brides scour the suq for days by themselves, and when they finally find the dress they like, they bring the groom along and pretend they just found it in the first store they’ve looked in, to show him they are decisive and practical. They want to please him, and even if I know different, I play along.

“The day Fadil sold his first dress, the customer thought he was very experienced because he knew where each model and each size was kept. When he started out, he gave bigger discounts than I approved because he wanted to make many sales. Selling wedding dresses to women is much harder than selling cars to men, because here you have to sell a complete ensemble, outer and inner wear. With a car, it’s just the outside.

“Fadil is now used to being around nervous women. My wife says he’ll make a good husband someday.”

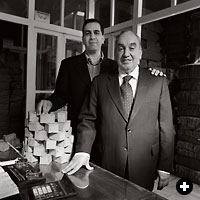

Musbah Fansa with son Fuad

Soap, Bab al-Faraj (Gate of Deliverance)

he Fansa family has been making and selling soap for generations. Aleppo has always been known not just for olive soap, which is common in many places, but laurel soap too, which only we Aleppines know how to make.

he Fansa family has been making and selling soap for generations. Aleppo has always been known not just for olive soap, which is common in many places, but laurel soap too, which only we Aleppines know how to make.

“My father, named Fuad like my son, started this business in 1952 under his own name, Fuad Fansa and Sons. That name is still stamped on every bar of soap we make, and we make a lot—about 500 tons a year. Whether it’s a tiny hotel soap or the big 240-gram [half-pound] bar we sell to beauty shops, they all say Fuad Fansa, my father’s name and my son’s name.

“My son is a mechanical engineer, trained in heating and cooling equipment, so he helped a lot to improve production in the factory. But there’s much we do the same as always: Pour the liquid soap straight onto the floor, then cut and stamp and stack by hand and air-dry it. And the caustic we use is still a natural ingredient. In the old days, we used a caustic made from a desert plant called qilliq, picked specially for the family by Bedouins near Palmyra, but it took five days to boil down. We don’t have time for that any longer, not with hundreds of tons of soap to make, and each batch made in a three-meter [10'] cauldron.

“Now we export to France and America and Japan. We use new shapes and sizes to appeal to foreign demand, and new scents like jasmine and rose, and special packaging printed in Japanese and French for export. Our boxes have a drawing of the Aleppo citadel and a map of Syria. We want to be known all over as Aleppo’s best soapmaker. We even registered our trademark in Japan, because you never know—we might expand into other products once we are well established there with our soaps. Fuad is building a website in other languages.

“We grade our soap depending on how much laurel oil it contains. We give either two or five stars depending on if we use two or five barrels of laurel oil per cauldron. We buy the laurel oil from Kassab, a town on the coast up near the Turkish border. I go there personally every fall to buy it. It’s expensive, about 400 Syrian pounds per kilo ($3.65/lb). We use second-pressing olive oil, which costs less than a tenth of that.

“Aleppo’s fine soaps originated in our hammam tradition, when the old men would gather at the bathhouse, and each wanted to show the others that his soap was the best. These bathhouses are not as popular now, but soapmaking continues. Europeans and Japanese want fancy soaps even if they are alone in the bathroom and no one else can see the soap. They want high quality and all-natural products above everything. In Japan they sell our soap in pharmacies, and in Europe the Green parties use it—at least that is what people tell me who travel there.”

Muhammad Sami Hakim and son Mamduh

Gold, Handkerchief Suq

y father had a clothes shop in the suq and set me up as a gold dealer when I was just starting out. He sent his steady customers to me, and I sent mine to him. That’s how it always works in any business, anywhere in the world—trust between buyers and sellers, and fathers giving special help to sons.

y father had a clothes shop in the suq and set me up as a gold dealer when I was just starting out. He sent his steady customers to me, and I sent mine to him. That’s how it always works in any business, anywhere in the world—trust between buyers and sellers, and fathers giving special help to sons.

“Syrians like to buy big pieces of jewelry, to show off to strangers, but foreigners buy smaller things. I don’t think they like gold so much. I sell French and English coins, Napoleon III, George V and Ottoman-period, too—all gold. Some people, those who don’t trust banks, like coins more than cash. My Bedouin customers prefer English and French coins to Ottoman. Don’t ask me why.

“It’s forbidden to sell gold and silver from the same shop, so customers trust that the gold they buy from me is pure, nothing plated or mixed. The daily price of gold is published in national papers, so people know what to expect even before they come into my shop. Even the Bedouins have satellite dishes now.

“July and August are my busiest months. When the harvests come in, the pockets of farmers and shepherds are full of money. The first thing they do is to buy gold, even if just as a temporary store of wealth. I think they like to see wheat and sheep turn to gold. When the rains are good, the gold market is good. You can see every year how one affects the other.”

Ayman Mehmeh

Drapery material, Khan al-Jumruk

he Khan al-Jumruk is the customs caravanserai, where English, French and Dutch merchants stored their goods until they cleared Ottoman customs in the 17th century. It is the suq’s largest khan, its oversized, iron-studded wooden door opening onto an unroofed courtyard, its lower stalls meant for bulk storage and animal stabling, its upper story for merchant lodging. Some 150 stalls today surround the khan’s lower level, all of which belong to merchants of cloth, from fancies to bulk quantities of Syria’s ubiquitous blue school-uniform fabric.

he Khan al-Jumruk is the customs caravanserai, where English, French and Dutch merchants stored their goods until they cleared Ottoman customs in the 17th century. It is the suq’s largest khan, its oversized, iron-studded wooden door opening onto an unroofed courtyard, its lower stalls meant for bulk storage and animal stabling, its upper story for merchant lodging. Some 150 stalls today surround the khan’s lower level, all of which belong to merchants of cloth, from fancies to bulk quantities of Syria’s ubiquitous blue school-uniform fabric.

“My grandfather started out in this business with three looms in his house, weaving fabric on demand. As a young man, my father opened a stall here selling fine factory-made textiles. Thirty years ago he started his own factory, weaving floor mats. Now we have mechanical looms and 40 employees making fine brocaded fabrics and silk tassels and braided ropes. I also sell thread wholesale to market manufacturers. Our export orders come from all the Arab countries—Yemen, Libya, Jordan, Iraq.

“In the old days, it was easy to start up a factory and buy equipment. Capital costs were low because it was all hand looming. Nowadays you need new machines of industrial quality. I am the first person to go to the bank to ask for a loan. If I cannot grow this business, we will soon shrink back to where my grandfather started. That is how it is selling textiles. You must sell what you yourself produce, and each year you must produce more.”

Salih Ibn Mansour

Animal skins and “eastern goods,” Main Suq

y father died when I was one year old, so I had no easy way to enter business in the suq. I began by gathering what others had cast off—old skins and broken bits of brass and copper, worn carpet and cracked glass. I have a good eye; I can see what is still of value, so I was able to resell these things quickly and make a profit. I also know how to stitch the farwas [sheepskin vests] worn by the Bedouins. I made them until my fingers ached, and sold them stall to stall, piled on my back. But now I can sit back here and wait for customers to come to me. I’ve been in this stall for 26 years, watching people walk past, and because it is at the top of the market, near the citadel gate, I often get lucky.

y father died when I was one year old, so I had no easy way to enter business in the suq. I began by gathering what others had cast off—old skins and broken bits of brass and copper, worn carpet and cracked glass. I have a good eye; I can see what is still of value, so I was able to resell these things quickly and make a profit. I also know how to stitch the farwas [sheepskin vests] worn by the Bedouins. I made them until my fingers ached, and sold them stall to stall, piled on my back. But now I can sit back here and wait for customers to come to me. I’ve been in this stall for 26 years, watching people walk past, and because it is at the top of the market, near the citadel gate, I often get lucky.

“I married at the age of 15 and now have many children. All have diplomas and none want to follow me in this work. They say it is not for them, that they cannot control their own destiny when they sit and wait for people to pass by and enter. But I say that destiny is in your own hands. Two years ago the stall across from me sold goat hides, a smelly business when the weather was damp and the hides had not been properly cured. But the owner changed his goods; now he sells fancy gold jewelry. I can do such a thing too—I can mend more than fleeces. I can repair all kinds of ‘eastern’ goods—water pipes needing refitting, copperware needing soldering, carpets needing patching. I can fix anything at all.”

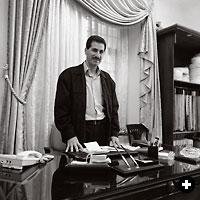

Alaa al-Din Labban

Men’s clothing, Sharia Quwatli

y family name means ‘yogurt-maker.’ Maybe 120 years ago, my family was in that business, but now it’s just clothes that we sell. I sell readymade clothes, all made in Syria, under the Reindeer trademark—that’s a British brand. I also sell custom suits, mostly to Russians—especially, it seems, to Russian pilots. There are so many direct flights to Moscow. I suppose someone has to fly all the Russian traders you see in Aleppo these days. I’ve worked in this store for 25 years, ever since I finished ninth grade. My father died and I had to take over his shop. I didn’t even have a minute to think it over. It was either that or have nothing in my life. So I took over, and I did well at my job. Only I soon switched from ladies’ to men’s clothes. Selling to ladies is much more difficult. They are so picky—too picky for me. But children’s clothes are even worse, because then you have to sell to picky kids and picky women at the same time.”

y family name means ‘yogurt-maker.’ Maybe 120 years ago, my family was in that business, but now it’s just clothes that we sell. I sell readymade clothes, all made in Syria, under the Reindeer trademark—that’s a British brand. I also sell custom suits, mostly to Russians—especially, it seems, to Russian pilots. There are so many direct flights to Moscow. I suppose someone has to fly all the Russian traders you see in Aleppo these days. I’ve worked in this store for 25 years, ever since I finished ninth grade. My father died and I had to take over his shop. I didn’t even have a minute to think it over. It was either that or have nothing in my life. So I took over, and I did well at my job. Only I soon switched from ladies’ to men’s clothes. Selling to ladies is much more difficult. They are so picky—too picky for me. But children’s clothes are even worse, because then you have to sell to picky kids and picky women at the same time.”

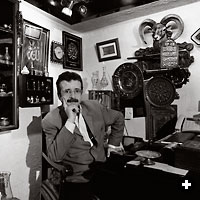

Adnan Mustafa Qaliyet

Fine antiques, Main Suq

aliyet’s glass-enclosed shop is piled to the ceiling with global bric-a-brac: African ivories, Sèvres porcelain, Aleppine brass, English cigarette lighters, Persian lacquerware, Damascene glass, Bedouin jewelry, Indian beads, Isfahani enamels and, displayed most prominently, old console radios specially made for Mediterranean and Middle Eastern markets, with tuning indicators for stations in Nice, Rome, Athens, Cairo, Rabat, Omdurman, Damascus and Tehran—a virtual gazetteer of colonial outposts and stopovers from the 19th century.

aliyet’s glass-enclosed shop is piled to the ceiling with global bric-a-brac: African ivories, Sèvres porcelain, Aleppine brass, English cigarette lighters, Persian lacquerware, Damascene glass, Bedouin jewelry, Indian beads, Isfahani enamels and, displayed most prominently, old console radios specially made for Mediterranean and Middle Eastern markets, with tuning indicators for stations in Nice, Rome, Athens, Cairo, Rabat, Omdurman, Damascus and Tehran—a virtual gazetteer of colonial outposts and stopovers from the 19th century.

“For a hundred years, my family has had a shop right here. I remodeled it 13 years ago to appeal to tourists looking for souvenirs from all over the world. My father Mustafa died 20 years ago at the age of 105. He was a great family patriarch. He started this store back in the Ottoman period. At one time my father owned half the stalls in the entire suq. He was the landlord to spicemen and butchers, goldsmiths and ropemakers.

“I see tourists from every country in the world come to Aleppo to look for their favorite things. Germans come for gold. Americans come for carpets and coins. The French come for silver and lapis, Greeks come for amber, and Japanese come for medicinal plants and soap. I know what to offer them as soon as I hear what language they speak.”

|

ALEPPO THROUGH TRAVELERS’ EYES ALEPPO THROUGH TRAVELERS’ EYES

IBN AL-SHIHNA (LATE 15TH CENTURY):

“Sales of a single day in Aleppo are often greater than those of a month in other cities…. Ten loads of silk, for instance, brought to Aleppo, are sold that very day for ready money, whereas ten loads taken to Cairo, though the largest of cities, are not sold there till the end of the month.”

GERTRUDE BELL,

AMURATH TO AMURATH (1911):

“A virile population, a splendid architecture, the quickening sense of a fine Arab tradition have combined to give the town an individuality sharply cut, and more than any Syrian city she seems instinct with an inherent vitality.”

JOHN HATT, “SYRIA,” WWW.TRAVELINTELLIGENCE.NET (2004):

“This souk must be the most enticing in the Middle East…. You are safe everywhere, probably several hundred times safer than in New York. You aren’t hassled by shopkeepers or cheated by taxi-drivers. And so many people invite you for coffee or tea that after a few days you start to suffer from severe caffeine poisoning.”

|

Ola Al Kassir

Benetton clothing, Aziziyah

graduated from a commercial-training institute and now work in the children’s department. I can move to any other department as needed. I have no plans for the future. I just like selling and wearing clothes. Benetton is the most expensive brand you can buy in Syria. Even if I cannot afford to buy a lot, at least I can see them all here every day.”

graduated from a commercial-training institute and now work in the children’s department. I can move to any other department as needed. I have no plans for the future. I just like selling and wearing clothes. Benetton is the most expensive brand you can buy in Syria. Even if I cannot afford to buy a lot, at least I can see them all here every day.”

Abdelrahman Qali

Tent cloth, Main Suq

ali, like Adnan Mustafa, belongs to the Qaliyet family, which holds a place of distinction in the suq as one of the major landlords in days gone by. His shop is filled with huge spools of woven white cotton rag, 1.5 meters (5') wide, similar in weight and quality to a heavy Indian dhurry rug and here called shaqqa. The shaqqa is unspooled and then cut to a tent’s desired width, normally either 15 or 30 meters (50 or 100'). Either four or 10 panels are then sewn together side-to-side to make the tent, either six or 15 meters (20 or 50') deep.

ali, like Adnan Mustafa, belongs to the Qaliyet family, which holds a place of distinction in the suq as one of the major landlords in days gone by. His shop is filled with huge spools of woven white cotton rag, 1.5 meters (5') wide, similar in weight and quality to a heavy Indian dhurry rug and here called shaqqa. The shaqqa is unspooled and then cut to a tent’s desired width, normally either 15 or 30 meters (50 or 100'). Either four or 10 panels are then sewn together side-to-side to make the tent, either six or 15 meters (20 or 50') deep.

“We sell tenting for both winter and summer: white cotton for summer, black goat-hair for winter. Even the white cotton tents we call bayt sha‘r, ‘house of hair.’ All Syrian tribes use the same shape tent, but they decorate the interior according to their own customs and designs. The goat-hair panels we have made specially for us in the village of Jisr al-Shughur. They have to work on hand looms. Mechanical looms can work in cotton but not with hair.

“There are only two tent shops left in the Aleppo suq. Business is dying. Ten years ago we could sell 100 tents in a year to individual buyers. Now it’s down to 40. I sold one to a German man who was opening an Arabian coffeehouse in Aachen and wanted a tent in the courtyard as a fantasy place. Maybe that is the future for our tents, as curiosities for foreigners.

“We keep up the wholesale business by selling to smaller shops in tribal areas, near al-Raqqa and Deir al-Zawr, al-Hazzakiah and Mayadin and Qamishli. We sell maybe 300 tents a year there. Look at a map of Syria—the tribal regions are east of here, along the Euphrates, and north along the Turkish border. That is our market, and as long as people continue to live in those areas, they will continue to live in tents, and they will have to do business with me.”

Abdel Rizaq Bakir

Rope, Ropemakers’ Suq

open my stall at 8:30 every morning and have done since 1952, when I first came to the suq. In those days the other stallkeepers called me ‘son,’ but now everyone calls me ‘grandfather.’ I guess it’s true that I have changed over the years. Before, I wore country clothes, and now I dress like anyone else in the city. But I still sell just rope and cording, some made of plastic and some that I make myself of hemp.

open my stall at 8:30 every morning and have done since 1952, when I first came to the suq. In those days the other stallkeepers called me ‘son,’ but now everyone calls me ‘grandfather.’ I guess it’s true that I have changed over the years. Before, I wore country clothes, and now I dress like anyone else in the city. But I still sell just rope and cording, some made of plastic and some that I make myself of hemp.

“Rope is less useful today than it was before. For automobiles you need chains, not ropes—that much I know, even though I don’t drive. But people still come here to buy it. They have not changed the name of this suq, after all. Most of my cotton ropes I sell to Bedouins for tentmaking, to stitch panels together or to trim tent pillows. I also sell ropes they use to draw water from wells.

“My sons are not ropemakers. One is a goldsmith; another, a plumber; others a mechanic and a tailor. They tell me—and I tell them—there is no future here for ropemakers, so I am glad they are somewhere else. Even though I pay only 5000 Syrian pounds ($100) a year to rent this stall, I do not always turn a profit. The suq fire of 1980 almost finished me. I lost all my stock, worth 40,000 pounds ($800), and only with God’s help was I able to collect my outstanding debts and get back to selling.”

Abdelrahman Nahhas

Copper goods, Copper Market

y grandfather, who also had my name, started out 70 years ago in this business making small pieces. He was the family’s first real coppersmith, so he gave us our name. My father began exporting old copper, mostly covered trays and table lamps, to Europe, but to satisfy demand there, he had to manufacture new pieces that looked old. Most of my own business is custom work, one-of-a-kind pieces ordered by interior designers and architects, sized as big as you can imagine. I sent an 11-meter (35') hanging chandelier to the [Arabian] Gulf. It looked like the bottom of a flying saucer. It took 10 men a month to make it, working nonstop. I have an order now for 200 pierced-sheet sconces to hang in a new hotel’s corridors. It seems that every hotel and restaurant in every Arab country is hung with lamps from Aleppo.”

y grandfather, who also had my name, started out 70 years ago in this business making small pieces. He was the family’s first real coppersmith, so he gave us our name. My father began exporting old copper, mostly covered trays and table lamps, to Europe, but to satisfy demand there, he had to manufacture new pieces that looked old. Most of my own business is custom work, one-of-a-kind pieces ordered by interior designers and architects, sized as big as you can imagine. I sent an 11-meter (35') hanging chandelier to the [Arabian] Gulf. It looked like the bottom of a flying saucer. It took 10 men a month to make it, working nonstop. I have an order now for 200 pierced-sheet sconces to hang in a new hotel’s corridors. It seems that every hotel and restaurant in every Arab country is hung with lamps from Aleppo.”

Hussam Dashirni

Internet cafe and pastry shop, Sharia Qawatli

e opened this shop three years ago, my seven brothers and I. I’m the baker and my brother Ziyyad is the Internet manager. The others fill in as needed. My brother thought up the name for the shop, ‘Concorde.’ He said people would think of speed and quiet at the same time, just like traveling on the supersonic airplane. We serve a lot of milk cake, ice cream and basbousa. For Ramadan, we make the Syrian specialties ma‘rouk and ghazal al-banat, several kilos a day of each. Many young couples come here to eat pastry together. The Internet customers are mostly men; they drink black coffee and sit at the keyboards for hours.”

e opened this shop three years ago, my seven brothers and I. I’m the baker and my brother Ziyyad is the Internet manager. The others fill in as needed. My brother thought up the name for the shop, ‘Concorde.’ He said people would think of speed and quiet at the same time, just like traveling on the supersonic airplane. We serve a lot of milk cake, ice cream and basbousa. For Ramadan, we make the Syrian specialties ma‘rouk and ghazal al-banat, several kilos a day of each. Many young couples come here to eat pastry together. The Internet customers are mostly men; they drink black coffee and sit at the keyboards for hours.”

Ghassan al Hussein

Appliances, Sharia Qawatli

’ve had this shop for 10 years. I sell microwaves and vacuum cleaners, water coolers and purifiers, washers and driers and space heaters. Most of my customers are men. I have no idea if the things they buy for their wives are given as gifts or as necessities, but I am sure their wives are glad to see something new come through the door. Modern appliances make their lives much easier, and they run more quietly, so the man is never bothered. He hardly even knows that his wife is working.”

’ve had this shop for 10 years. I sell microwaves and vacuum cleaners, water coolers and purifiers, washers and driers and space heaters. Most of my customers are men. I have no idea if the things they buy for their wives are given as gifts or as necessities, but I am sure their wives are glad to see something new come through the door. Modern appliances make their lives much easier, and they run more quietly, so the man is never bothered. He hardly even knows that his wife is working.”

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a free-lance writer and contributing editor to Americas magazine. He lives in New York. |

|

Free-lance photographer Kevin Bubriski (bubriski@sover.net) recently published Pilgrimage: Looking at Ground Zero (2002, Powerhouse). His photographs are in numerous museum collections worldwide. |

|

|