Written by Louis Werner

Photographed by Toby Savage

e looks down on the Wadi al-Hayat, the Valley of Life, from his perch high up on the escarpment. His face is weathered but still shows the firm lines of the pointed chin that distinguished his people in the wall paintings of the pharaohs. To them, he would have been known simply as a Libyan, but among the ancient Libyans there were many different tribes, none stronger or more skillful at desert travel than his. Herodotus was the first to call his people by their proper name, the Garamantes, and to correctly locate his homeland in the Fezzan Oasis, in Libya’s southwestern corner.

e looks down on the Wadi al-Hayat, the Valley of Life, from his perch high up on the escarpment. His face is weathered but still shows the firm lines of the pointed chin that distinguished his people in the wall paintings of the pharaohs. To them, he would have been known simply as a Libyan, but among the ancient Libyans there were many different tribes, none stronger or more skillful at desert travel than his. Herodotus was the first to call his people by their proper name, the Garamantes, and to correctly locate his homeland in the Fezzan Oasis, in Libya’s southwestern corner.

|

|

Once the seat of a power that controlled much of southwestern Libya’s Fezzan region, Old Garama exists aboveground as ruins that date from the early Islamic era. Here and in nearby sites, other

evidence shows settlement from the ninth century BC. |

But this tribesman himself remains nameless, and he has been dead for more than 2000 years. His face is carved into the rock at a place called Zinchechra, which overlooks what Pliny the Elder called clarissimumque Garama caput Garamantum: “well-known Garama, capital of the Garamantes.”It is this Garama, lying today beyond a dried moat and behind crumbling walls, underneath a mud-brick town built early in the Islamic era, that recently has been the object of a British archeological expedition that is slowly bringing this once great Saharan civilization to light.

The Garamantes ruled this central, interior part of North Africa for 1000 years or more, from about 500 BC till about AD 500. Their origins are still being debated, though they were probably of a Berber ethnicity. We do know they developed a stable kingdom based on wadi agriculture, intensive irrigation and cattle pastoralism. Their written language was a still nearly indecipherable proto-Tifaniq, the script of modern-day Tuaregs.

The Garamantes’ portrait shares the rock face with other carved images—an ostrich hunt, a giraffe and a horseman—that call to mind the tremendous wealth of rock art, dating from the late Paleolithic through to the early modern era, found throughout the Sahara. It is especially abundant in Libya’s Jabal (Mount) Akakus and Messek (Plateau) Sattafet, upon which Zinchechra stands.

Herodotus wrote of the Garamantes’ four-horse chariots, which are pictured in rock carvings and paintings at many nearby sites. He also described their agricultural practice of strewing earth upon the salt plain before sowing their crops, noting correctly the high natron (bicarbonate of soda) content of the Fezzan soils. More fancifully, he also wrote that the Garamates bred cattle with horns so large that the animals were obliged to walk backward as they grazed, dragging their horns behind them like plows.

Such tall tales of the Garamantes are common among the classical authors who mention them. Pliny wrote about a Garamantes town called Thelgae, near which a spring issued water that boiled at midday and froze at night. Perhaps more realistically, he also described the Garamantes guerrilla tactic of filling desert wells with sand when in retreat in order to throw off pursuers. Tacitus called the Garamantes “an ungovernable tribe and one always engaged in brigandage against its neighbors.”

The second-century Greek satirist Lucian, whose True History parodies the fantastic geographies of his literary forerunners, wrote that the Garamantes lived in tents and hunted apes. Herodotus, writing from Cyrene on the Libyan coast, got many things right about them but got one big thing wrong, calling them shy and reclusive—“they have no warlike arms at all,” he wrote, “nor do they know how to defend themselves.”

|

|

| In one of the area’s many pictographs, people appear to gather for either harvest or ceremony. The image dates to the beginning of settled life in the Fezzan, which was prompted in part by the desiccation of the Sahara, which by the second millennium BC had greatly reduced the productivity of hunting. |

The Roman poet Virgil made the Garamantes’ lands into a metaphor for the very ends of the earth. In Book Six of the Aeneid, Anchises speaks to Aeneas from the underworld to prophesy the great Romans yet to come: “This is the man you heard so often promised—Augustus Caesar, who will renew a golden age in Latium and stretch his rule beyond the Garamantes,...a land beyond the paths of year and sun, beyond the constellations, where on his shoulders heaven-holding Atlas revolves the axis set with blazing stars.”

Even a contemporary Libyan author, Ibrahim al-Koni, in his 2002 book The Bleeding of the Stone (Interlink Books), builds upon the mythology of the Garamantes heartland. In this novel of magical realism about the extinction of the mouflon, a Saharan wild sheep, he writes, “They’d crossed the plain now, and the Massak Satfat was becoming visible. The heights, covered with huge black rocks, burned in the sun’s everlasting fire. The peaceful sandy desert, stretched out flat and merciful to God’s worshipers, ended, and the mountain desert began, angry and inhospitable, its face set sternly against the wanderer. The rancor was, it seemed, a legacy of those remote times when unending battle was waged between the two harsh deserts, a fiery enmity even the gods in the upper sky had never contrived to soften or reconcile.”

Perhaps Strabo the Geographer should have the ancients’ last word. “Most of the peoples of Libya are unknown to us,” he wrote. “Only do very few of the natives from far inland ever visit us, and what they tell us is not trustworthy or complete.”

Sa’d Salih Abedelaziz has information more up-to-date than Strabo’s. Abedelaziz is director of the new Garamantes museum at Germa—the present-day name of Garama—and for the past nine years he has been taking part in the British area survey and excavations. As a lad living in what was then Germa village, he remembers the work of the first modern archeologists to examine Garamantes sites: Mohammad Ayoub, a Sudanese official in the Libyan Antiquities Department, and Charles Daniels, an Englishman. “I would ride my bicycle out to see what they were doing,” says Abedelaziz, “but I was still too young to know anything about the Garamantes.”

Even now, however, Abedelaziz and other experts on the Garamantes are better at discounting old theories than at positing anything new and definitive. Abedelaziz notes the long-held bias, classical Greek and Roman as well as modern European, against any thought that the Sahara might once have been a cradle of civilization. Italian archeologists, working in the 1930’s at the height of their Libyan colonization, thought the Garamantes must have been of Phoenician, Egyptian or Mediterranean origin. Considerations of how and why they might have arrived in Fezzan across vast tracts of desert were less important than the Italians’ need to deny the possibility of indigenous African ingenuity.

Even now, however, Abedelaziz and other experts on the Garamantes are better at discounting old theories than at positing anything new and definitive. Abedelaziz notes the long-held bias, classical Greek and Roman as well as modern European, against any thought that the Sahara might once have been a cradle of civilization. Italian archeologists, working in the 1930’s at the height of their Libyan colonization, thought the Garamantes must have been of Phoenician, Egyptian or Mediterranean origin. Considerations of how and why they might have arrived in Fezzan across vast tracts of desert were less important than the Italians’ need to deny the possibility of indigenous African ingenuity.

Ayoub’s work in Old Garama established three sequences of construction: the topmost Islamic city, a middle level of dressed stone foundations, and a bottom level of salt-brick work that seemed to be pre-Roman. Daniels’s excavations at Zinchechra established the earliest date for its various defensive and residential walls as the ninth century BC.

|

|

| The steep pitch of some 100 salt-brick funerary pyramids resembles counterparts in Sudan at Meroë, and stelae under the monuments resemble those of the Phoenicians, all testifying to the Garamantes’ far-flung connections. |

Daniels only worked in the area for a few years, and his 1979 book, The Garamantes of Southern Libya (Oleander Press), reached only tentative conclusions and ended with a shrug. “That so many questions still remain unanswered is not surprising,” he wrote, “for the Garamantes have guarded their secrets long and well, and we in our searching even now stand only on the threshold of their world.”

Since 1997, David Mattingly of the University of Leicester has fielded a team in Fezzan, sponsored by the UK-based Society for Libyan Studies, that hopes to cross that threshold. By dating organic remains in Old Garama to the fourth century BC, studying the irrigation tunnels known as foggara and documenting the Roman trade goods found in the area, Mattingly has been revising the long-held impression that the Garamantes were mere primitive troublemakers at the edge of the Roman Empire.

From the top of the Zinchechra cliff face, Abedelaziz waves his hand in the four cardinal directions to make his point that the Garamantes were, from a Saharan perspective, at the center of things, and not, as the Romans would have it, at somebody’s margin. Their centrality among several sources of highly valuable, low-weight trade goods such as gold, salt, glass and precious gems put the Garamantes on the world stage.

To the west is the oasis town of Ghat, the first in a string of caravan stages that lead first to Algeria’s Tassili n’Ajjer and Hoggar mountains and on to the Adrar des Iforhas in modern Mali, ending at the Niger River. To Garama’s east, through the oases of Waddan, Augila and Siwa—although not an easy trip—lies Egypt and the Nile.

To the north is the Mediterranean coast, reached via the historically important city of Ghadames, still the Sahara’s most perfect example of urban architecture. In AD 69, the Romans under Valerius Festus opened up a more direct route between Fezzan and the coast that Pliny called the “iter praeter caput saxi” (“the road past the head of broken stones”). This is uncannily close to what the modern Libyans still call this route via the towns of Gariyan and Mizda: Ras al-Hammada, or “the head of the stony plain.”

South of Fezzan, along the Chad border, are the Tibesti mountains. Looking at the map, one can imagine why the Nile, the Niger and the Mediterranean would be destinations of importance—but the Tibesti? If Pliny can be believed, Mount Gyri, source of the classical world’s highly treasured “carbuncle,” or garnet stone, is to be found there. The Emperor Trajan sent two trading expeditions in that direction, one led by Septimus Flaccus, Legate of Numidia, and the other by a merchant named Julius Maternus, who, again according to Pliny, arrived at “Agysimba, a province of the Aethiopians where the rhinoceros congregate.”

|

|

| A pre-Islamic mausoleum of dressed stone is inscribed in the proto-Tifaniq script of the Garamantes, foundation of the modern Tuareg script. |

Within eyesight of Zinchechra is more tangible evidence of the Garamantes’ connections with lands beyond their own. Their foggara, or irrigation tunnels, are similar in design and function to the qanats of contemporaneous Persia. Their steeply pitched pyramids mirror those of Meroë in the Sudan, and they usually contain tripartite funerary stelae that recall those of the Phoenicians. A fine mausoleum of dressed stone that the locals call Qasr Watwat, or “Castle of the Bats,” is decorated with Tifaniq inscriptions and columns with Corinthian capitals. Bits of Roman glass and fig seeds, pomegranate seeds and olive pits—all fruits imported from the coast—were common grave goods.

When in the second millenium BC the Sahara’s climate began to change from wet to dry and then toward its present extreme aridity, humans adapted, in part by shifting from nomadic hunting to settled pastoralism and agriculture: In rock painting, imagery of the time shifts from big animal hunts to scenes of cow milking, goat herding and human grooming. But this shift was not without its trials. A Libyan invasion of the Nile Valley in 1200 BC, documented in the Egyptian record, may have been prompted by this climatic discontinuity. More evidence is among the petrified tree trunks that lean against the walls of the Germa museum. “I know where forests of it still stand,” says Abedelaziz.

|

Settled agriculture required large-scale irrigation works that linked the near-surface water table at the escarpment to the fields of the central valley, a distance varying between one and three kilometers (1000 yds–1.8 mi). The underground foggara, built as early as the sixth century BC with bricked and cemented galleries and vertical cleaning shafts at regular intervals, are like those built in Egypt’s Bahariyya Oasis in the 26th Dynasty and by the Romans centuries later in Tunisia and Algeria. Abandoned long ago, traces of the foggara are still visible everywhere in the wadi. The mounded debris pulled from their shafts looks like evenly spaced dots linking cliff face to farmland.

These foggara required intensive labor for both construction and maintenance. Within one six-kilometer (3.6 mi) stretch, some 60 individual systems have been counted. A staggering total of as much as 20,000 kilometers (12,000 mi) of south-to-north foggara may have existed within the wadi’s 130-kilometer (80-mi) east-west length. Based on demographic models, the estimated 120,000 tombs imply that the stable population of the valley may have reached 10,000 people. How the labor was organized and how the workers were motivated remain outstanding questions, but perhaps there was a central authority: a Garamantes king.

The wadi’s best-known cemetery is nearby at al-Hatiya, where some 100 tightly clustered, salt-brick pyramids once stood five meters (16') tall. Most contained stone offering tables and stelae in off-center graves, connected one to another through crawl spaces. Abedelaziz notes how grave robbers often missed the tombs by digging directly underneath the pyramids rather than beside them. Even so, the pyramids are in fairly good condition because, in rain, saltbrick hardens rather than softens. According to Pliny, the Garamantes “built their houses from salt extracted from their mountains like stone.”

|

|

| A high water table continues to support modern agriculture in old Garamantes territory. Pumps and pipes have replaced the network of stone foggara, or underground irrigation tunnels, that once may have totaled as much as 20,000 kilometers throughout the valley. |

Salt proved helpful in another way. Its presence on the surface helps to hold the water table up close to the ground. When the Garamantes spread earth on the salt to plant the crops, as Herodotus reported, they may have been taking advantage of this principle. Even so, over the last century, the wadi’s water table has been dropping. In 1820, the English explorer Walter Oudney counted some 340,000 date palms in the oasis. As the water table fell, many died, and the shallow wells have gone dry; however, where there are high salt concentrations in the soil, palms survive.

This surprising link between water and salt is illustrated also in the so-called daw-wada (“worm people”) lakes, some 20 kilometers (12 mi) north of the wadi, in the midst of the Zellaf dune fields that are the easternmost extension of the Ubari Sand Sea. These saline lakes, so high in natron that it is difficult to keep one’s overly bouyant legs beneath the body when treading water, are the products of fractures in strata between the surface and a deep, underlying aquifer.

The lakes got their name from the original human inhabitants of their shorelines, who annually harvested the crustacean Artemia salina (brine shrimp) from the lake waters. Oudney came upon 20 camels waiting for their “worm” loads, and he described the cargo with some disgust: “small animals, almost invisible to the naked eye, surrounded by a large quantity of gelatinous matter, of a reddish brown color and strong slimy smell.”

Ancient Garama was not finally abandoned until 1937, when the Italian colonists decided that its soil, which had grown progressively more swampy, had become a public health hazard. Abedelaziz remembers as a boy swimming in the moat that surrounded the 10-hectare (25-acre) city, and he recalls his grandmother returning by day to water her palms and garden. “One of her neighbors is Abdul Hafiz Abu Bakr Raghrughi, now 116 years old,” says Abedelaziz. “He still walks to the mosque every day with a straight back, just as when he left his house in the old city 65 years ago.”

Ancient Garama was not finally abandoned until 1937, when the Italian colonists decided that its soil, which had grown progressively more swampy, had become a public health hazard. Abedelaziz remembers as a boy swimming in the moat that surrounded the 10-hectare (25-acre) city, and he recalls his grandmother returning by day to water her palms and garden. “One of her neighbors is Abdul Hafiz Abu Bakr Raghrughi, now 116 years old,” says Abedelaziz. “He still walks to the mosque every day with a straight back, just as when he left his house in the old city 65 years ago.”

For archeologists, the dating and sequencing of human habitation in Garama is still far from clear. The old city had three mosques which are now, like the rest of the city, in ruins. Under two of them have been found cut-stone foundations with some indication that they had been temples to the Phoenician goddess Tanit, who in another guise was worshiped at Meroë in the Sudan—perhaps under the distant influence of the Garamantes.

|

|

|

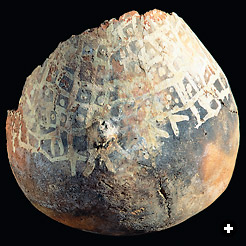

|

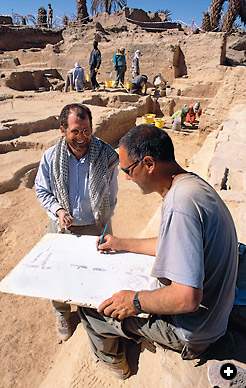

| Above: A fragment of a decorated pot and an inscribed stone are among the artifacts under study both by Libyan specialists in the nearby modern town of Germa and by British archeologist David Mattingly, below, standing, who has been excavating in Old Garama since 1997. |

|

|

The Romans did not conquer the Garamantes so much as they seduced them with the benefits of trade and discouraged them with the threat of war. The last Garamantes foray to the coast was in AD 69, when they joined with the people of Oea (modern Tripoli) in battle against Leptis Magna. The Romans intervened and marched south. According to Edward Bovill, author of The Golden Trade of the Moors, this campaign marked the Romans’ first use of camels in the Sahara, which convinced the Garamantes that their advantage in desert warfare no longer held.

The Italian historian Mario Liverani thinks that the Garamantes’ greatest legacy to the outside world is in fact their prowess in Saharan travel. The measured routes, daily stages, mapped mountain passes and rough bypasses around such no man’s lands as the basaltic Haruj al-Aswad (“The Black Narrows”) were used by centuries of later caravaneers, and many are still followed by today’s truck drivers. That in the Islamic period the Fezzan’s capital shifted one wadi south from Garama to Murzuk meant simply that the north-south trade axis between Tripoli and Nigeria had gained in importance, and Garama had fallen off the main route.

But when in 667 the Muslim conqueror of North Africa, ‘Uqba ibn Nafi, reached the Libyan town of Waddan, he asked the townspeople if there was any place of importance further into the desert. Only Garama, he was told, 10 days’ march away. This echoed Pliny, who wrote that “you reach the territory of the Garamantes after marching westward for 11 days across the Syrtis Major.” So Ibn Nafi set off, according to Ibn Khaldun, with 400 horsemen and 400 camels and 800 waterskins, and brought Islam to the Garamantes.

Garama’s most recent building of significance dates from the year 1557, when its kasbah, or citadel, with seven three-storied towers, now in ruins, was constructed. It was the work of Garama’s overlord from Fez, Muhammad al-Fassi, undertaken as he was returning from a pilgrimage to Makkah, says Abedelaziz. Al-Fassi’s sons, al-Nasir and al-Muntasir, married locally and it was they who moved the capital to Murzuk.

Garama’s star was long faded by 1818, when Britain assigned the 29-year-old Scottish surgeon Joseph Ritchie to serve as consul in Murzuk. He arrived quite unprepared for the rigors of Saharan life and was dead of fever in less than six months. Some of his least appropriate gear, including a camel-load of corks to which to pin collected desert insects, was passed to fellow entomologist Walter Oudney, who wrote amazed from the Fezzan of “the number of ants of species different from any I have seen elsewhere in North Africa.”

The re-exploration of ancient Garama by the British—archeologists, not entomologists, this time—would seem to take up where the colonial past left off, were it not for the participation of local scholars like Abedelaziz. Much remains to be learned, and their work to date has been as much surveying across the wadi as it has been digging into it.

But perhaps the answer to the mystery, “Who were the Garamantes?” is right under our nose. An aged grandfather of the Tuareg, today’s dominant tribe in the central Sahara, was recently asked to look at an old inscription found in the village of Bint Bayya and dating perhaps from the Garamantes period. With great difficulty, he was able to decipher the proto-Tifaniq script. “My name is Konja,” he read, and the name is a common one among the Tuareg today.

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a free-lance writer, photographer and filmmaker living in New York. He thanks Wings Travel in Tripoli (wingstravel@yahoo.com) for field support. |

|

Toby Savage (www.tobysavage.co.uk) is an advertising, travel and archeological photographer who has served as expedition photographer for the Society of Libyan Studies. He lives in Leicester, England. |