|

|

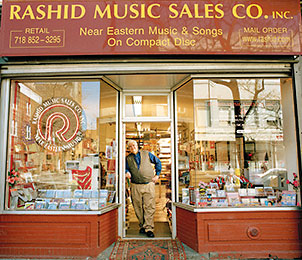

| Raymond Rashid welcomes customers to the family store at 155 Court Street. It’s the third location for the 55-year-old business, founded when Ray was two years old. |

Written by Marc Ferris

Photographed by Naomi Harris

tep a block and a half off Brooklyn’s busy Atlantic Avenue into the modest storefront of Rashid Music Sales, and you can feel that you’re entering a time warp: Black-and-white stills from classic Arab films hang on the wall. The floor is checkerboard tile, and beyond the small showroom, rows and rows of metal shelves hold boxes filled with Arab-music cds. It looks as if a musical archive had taken over a 1950’s soda shop.

tep a block and a half off Brooklyn’s busy Atlantic Avenue into the modest storefront of Rashid Music Sales, and you can feel that you’re entering a time warp: Black-and-white stills from classic Arab films hang on the wall. The floor is checkerboard tile, and beyond the small showroom, rows and rows of metal shelves hold boxes filled with Arab-music cds. It looks as if a musical archive had taken over a 1950’s soda shop.

It’s a humble setting for the United States’ oldest and largest purveyor of Arab music, a family-owned business that almost closed its doors in 2001. Now in the hands of 57-year-old Raymond Rashid, one of founder Albert Rashid’s two sons, the business is stronger and better-known than ever, offering recordings found nowhere else in the country and mining its own holdings to release historical recordings that are putting a new generation in touch with virtuosos of the past.

In the United States, few people have done more than the Rashid family to keep Arab musical traditions alive. “There’s no one like them. They have a deep historical consciousness, a sense of culture,” says Ali Jihad Racy, professor of ethnomusicology at the University of California at Los Angeles. “They’re more than sellers of good music; they’re like an institution that has furnished the country with so much of the artistic heritage of the Arab world.”

|

|

| Ray holds a photo of his father, Albert Rashid, who posed with the Egyptian Mohammed Abdul Wahab (with fez) during Albert’s visit to Cairo in 1937, a time when he was beginning to import Arab films and music to the United States. |

The Rashids’ legacy stretches from the horse and buggy to the Internet. In 1920, nine-year-old Albert Rashid’s family left Syria and came to rest in Davenport, Iowa. Later, Albert sought work in Detroit, whose automobile factories were a magnet for Arab-Americans seeking work. His life changed in 1934, when he saw the Egyptian film “The White Rose,” with a soundtrack scored and performed by Mohammed Abdul Wahab.

By then he also possessed a newly minted degree in business administration from Wayne State University, and he began importing Arab films and showing them across the country. He also made a good living selling movie soundtracks and other recordings. He moved to New York City in 1949, and he opened a shop in Manhattan.

Work on the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel uprooted the Arab community that had grown up near the island’s southern tip, and with others Rashid relocated to Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. There, in 1951, he opened what became a legendary emporium that attracted Arab immigrants and other visitors to the United States, who all regarded it as a gathering place, something between a salon and an oasis. “People called that store an institution,” says Raymond. “It was a place they would come to after leaving their homes behind. My father always helped people locate a relative or acquaintance, find a newspaper with news from home or get the latest recordings.”

|

|

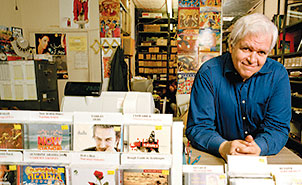

| Rashid stocks Arab pop and non-Arab “world music” in addition to the most extensive collection of Arab classical music for sale in the us. “I do a lot of research,” he says. “Sometimes I find music the labels didn’t even know they had.” Recently he’s tapped boxes of his father’s forgotten reel-to-reel tapes to publish a “Masters of Arabic Music” series. |

|

|

|

|

|

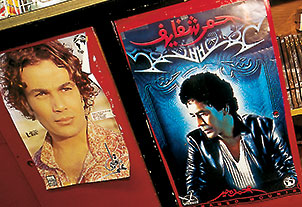

| Pop posters show, from left, Egyptian pop heartthrob Amr Diab and Mohammed Mounir’s latest release “Ahmar Shafafe” (“Red Lipstick”). |

Stan Rashid, Raymond’s older brother who helped run the business until he retired in 2001, remembers one well-known musician who received old-world hospitality at Rashid Sales. “This singer came in and didn’t have any money or anything,” he says. “We knew who he was and knew he was in bad shape, so my Dad gave him some money and said, ‘Pay me back whenever you can.’ The guy actually became very successful. He came back and said, ‘I’ll never forget what your father did for me.’ That’s the way my Dad acted with people.”

The influence of the Rashids’ business soon reached beyond the confines of the Arab-American world. Folk musician Pete Seeger wandered in one day, and another day Raymond provided music for a party given by artist Andy Warhol. Stan remembers the day Malcolm X visited. “He was looking for music on 45’s for the jukebox in his mosque in Harlem,” he says. “I was impressed by him more than anyone else who ever came into the store. I found him to be quite engaging and knowledgeable.”

The family also showed Arab movies at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Detroit Institute of Art, and in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Texas. They also mingled with local musicians, since Raymond himself played the dumbak (the goblet-shaped drum) as an amateur. Composer and international multi-instrument virtuoso David Amram recalls meeting Raymond at a jam session at Cafe Feenjon in Greenwich Village in the 1960’s. Thanks partly to such occasions, Amram incorporated Middle Eastern rhythms and melodies into several of his compositions. And of course, he stopped by the store to stock up on recordings. “I realized that here was a place where people not only loved the music as much or more than I did, but knew so much and had so many different kinds of music that I had never even heard of,” Amram says. “It’s still that way.”

In the 1980’s, the family began promoting concerts in the city, including the first Arab concert held in New York by the Manhattan-based World Music Institute, says Robert Browning, wmi’s executive director.

Browning’s institute sells discs from all over the world, and he gets the majority of his Arab titles from the Rashids. “They have the broadest range of styles imaginable,” he says. “Most places that do bring stuff in only deal with pop, whereas they import a variety of classical and regional traditional music.”

The brothers also supplied discs to major music retailers, including Tower Records, Virgin and HMV. Thanks to the Internet, they now sell around the world: Customers include a shepherd on the Baltic island of Gotland who likes Um Kulthum and a Saudi man who sought an archival recording of three Saudi singers that had been released in France. “He couldn’t find it over there, but we had it,” says Stan.

And when the composers of the soundtrack of the Dreamworks film “The Prince of Egypt” sought Arab music to inspire them, they too came to Brooklyn.

Raymond says he has made some changes since he took over the business, which moved to its present location on Court Street in 2000. In addition to giving the storefront a facelift and cataloguing every title, he has begun selling dj mixes and recordings by Arab rap groups, and he’s offering non-Arab world-music discs on the Putumayo label.

Perhaps most important, he’s joined with Michael Schlesinger of Global Village Music, advised by Rashid’s renowned Brooklyn musician neighbor Simon Shaheen, to tap the past for direction for the future. He has released eight new titles on the “Masters of Arabic Music” series, all culled from reel-to-reel recordings collected by his father that were mostly stored in unmarked boxes.

One find included a recording of a 1952 Cairo concert by Farid Ghosen, whom Raymond likened to Paganini and whose discs disappeared after his death in 1985.

“Ghosen was a remarkable performer,” says Racy. “To have this made available again is a revelation! Who knows what else Ray is going to find?”

|

Marc Ferris (mferris@bestweb.net) is a free-lance writer based in Dobbs Ferry, New York. He also contributes regularly to The New York Times and Newsday. |

|

Naomi Harris (naomiharris@earthlink.net) is a free-lance photographer living in New York and Toronto. World Press Photo has selected her to represent Canada in this fall’s annual photojournalist’s masterclass in Amsterdam. |