was curious: Would Saudi-grown khalasahs taste better, or significantly different? There was only one way to judge: an on-the-spot taste test. On my flight to Dammam, the nearest international airport to the oasis of al-Hasa, I carried three of my California khalasahs. They represented the best of the best, and they were there to help me make fair comparisons.

was curious: Would Saudi-grown khalasahs taste better, or significantly different? There was only one way to judge: an on-the-spot taste test. On my flight to Dammam, the nearest international airport to the oasis of al-Hasa, I carried three of my California khalasahs. They represented the best of the best, and they were there to help me make fair comparisons.

|

|

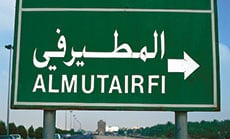

| Few roads in al-Hasa lead to al-Mutairfi, but those that do lead to the best of the best. |

|

|

|

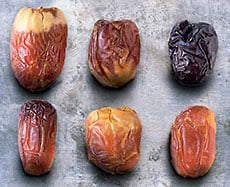

| Six of the leading varieties from diverse regions of the kingdom: sekki, sukkari, ‘ajwah, dekieri, nubout sayf and khlas. |

I also wanted to sample a broad selection of the many Saudi date varieties that I had heard about, especially the ones that are not widely available outside the kingdom. Many residents and date connoisseurs from throughout the Middle East, Asia and Africa consider the khalasah, known in Saudi Arabia as khlas, and whose Arabic name loosely translates as “quintessence,” to be the very best. Hofuf, the main city of the al-Hasa Oasis, in the kingdom’s Eastern Province, is its home, and from what I had read, the roughly 100 date growers from the Al-Mutairfi village in the oasis are considered to be the undisputed masters at growing the khlas. I arrived at the end of the date-harvest season, which lasts from May through October.

Al-Hasa, known as Hajar in ancient times, covers about 20,000 hectares (50,000 acres) and it is said to be the largest date palm oasis in the world. The quality of its approximately 100 natural springs and artesian wells, some of them hot, the elaborate irrigation system, the well-drained, alkaline, sandy soils and the intense heat all make this area ideal for date cultivation, a practice that goes back at least 4000 years. The other primary date-growing areas in the kingdom are around the oasis cities of Qasim, Qatif, Bishah and Islam’s second-holiest city, Madinah, which hosts the kingdom’s most extensive date market. From region to region, the most popular dates include khlas, khunaizi, bukayyirah, gharr, shaishi and ruzaiz in the Eastern Province, and nubout sayf, sufri, barhi, sukkari, sullaj and khudhairi in Qasim and the rest of the Central Province. In the west, including Madinah, people mainly favor ‘anbara, ‘ajwah, rothanah, baidh, rabi‘ah, barhi, hilwah, hulayyah, safawi, shalabi and sukkari. Part of the reason that people in each region consider their own dates the best is because horticultural practices, soil, water and climate favor different dates in different areas. For example, the sukkari dates in al-Hasa are very good, but as a general rule, they are not considered quite as good as the sukkari dates from Qasim or Madinah.

According to the Turkish census of 1871, approximately two million date palms then grew in and around Hofuf. And it was at about that time that the English traveler William Gifford Palgrave described the khlas of al-Hasa as “the perfection of the date.” For centuries, khlas dates have been exported to India, Zanzibar and throughout the Middle East—but, like all premium date varieties within the kingdom, the khlas is primarily for domestic consumption. The American botanist and date hunter Paul B. Popenoe, author of the 1913 volume Date Growing in the Old World and the New, tried to visit Hofuf the year before his book was published to buy khlas jebbar, or offshoots, but the Turkish authorities could not guarantee his safety. In 1914, the date-growing region was taken from the Turkish forces by the growing power of the future founder of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa‘ud, and since then has been under Saudi rule.

Before heading south to Hofuf, I visited several retail date outlets in the Eastern Province cities of al-Khobar and Dammam. I located the upscale retail date store Batil in al-Khobar’s shiny Al-Rashid Mall. Surrounded by world-brand shops such as Estée Lauder, Body Shop, Swatch and Lacoste, Batil offered a changing assortment of 80 different varieties of dates, depending on the season. The display reminded me of a quality chocolate store where customers can select individual varieties and then have the assortment gift-wrapped.

At Al-Fateh Dates in Dammam, I met owner Abdullah al-Ghamdi. He is said to be the first store owner in Saudi Arabia to make date ice cream, but what caught my eye was his selection of rare varieties of dates from the different growing regions. To my good fortune, al-Ghamdi turned out to be somewhat of a date historian. We sampled several varieties: sukkari, khlas, ‘ajwah and nubout sayf. Then I pulled out my three California-grown khalasahs for comparison.

|

|

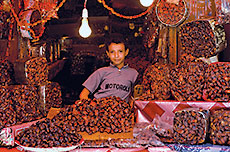

| In Sana’a, Yemen, a young vendor sells dates imported from Saudi Arabia. All are sorted and priced by variety and ripeness. |

Al-Ghamdi looked at my dates and laughed, politely. “We have a very old classical Arabic saying,” he said. “‘Carrying dates to Hajar,’ or ‘Hamil al-tamr ila Hajar.’ It is like the English expression ‘Carrying coals to Newcastle.’”

Al-Ghamdi evaluated my best-quality California khalasahs without tasting them. “We call these dates hawheel,” he said. “They are the dates from last year’s harvest. The skin is dry and blistered, and—see here, where the sugar is crystalizing? Without tasting it, I know the complexity of flavor has deteriorated. They are edible, but we sometimes feed hawheel dates to the donkeys, sheep and goats.”

The following day I met a friend of al-Ghamdi’s, Muhammad Tahlawi, for whom dates are more than a matter of connoisseurship: They are one of his lifelong passions.

“The first date of the season,” he told me, “is the bukayyirah. We have an expression about this date: ‘Awwalha lil amir, wa akhirha lil hamir.’ In English this means, ‘the first of the crop is for the amir, or governor, and the last of the crop is for the donkey.’”

Tahlawi went on to explain that bukayyirah means “early one,” and growers once challenged each other to see who could deliver the first dates of the year to the town’s amir. But later in the season, once other dates of better quality and flavor became available, the bukayyirah was fed exclusively to the donkeys.

When I asked Tahlawi about the ripening sequence of the kingdom’s date varieties, he immediately began counting them on his fingers: “bukayyirah, maji, gharr, ruzaiz, khusab, mijnaz, khunayzi, khlas, shaishi, shihil, barhi, sukkari, hilali, um ruhaym….” The recitation seemed to go on for several minutes without pause. “There are approximately 240 to 360 different varieties of dates, depending on whom you talk to, but these are just some of my favorites,” he laughed.

“Which are the best dates?” I asked.

“It is all a matter of personal preference and what is available locally,” Tahlawi replied. “Different dates grow differently and taste different from place to place, and even within one date grove you will find a range of qualities in the same variety. Date varieties often taste better in areas where they have been grown for a long time. Part of this is due to the quality of the water, the type of soil and specialized local growing techniques. For this reason each region can rightfully claim that their dates are the best.”

|

|

| Abdullatif Alkhateeb, director of the Date Palm Research Center in al-Hasa, holds in vitro seedlings that will bear fruit 30 percent more quickly than traditionally grown palm offshoots. |

|

|

|

| Date palm workers in Saudi Arabia generally use a climbing harness, not a ladder. |

|

|

|

| Workers in al-Mutairfi wash and sort khlas dates according to color, size and condition. The entire crop from premier producers is pre-sold to wholesalers in the kingdom and Gulf countries. |

We discussed famous dates that I had read about but never tasted. “Amir al-hajj?” I asked. Tahlawi explained the name meant “commander of the pilgrimage [caravan].” This date, he said, is “very rare. Orange-brown and very translucent with a caramel taste. But it is an Iraqi date, from the oasis of Mandali, east of Baghdad. In Iraq dates are sometimes filled with clotted cream from the milk of water buffalo.”

“I have heard that the ‘ajwah date, from Madinah, was the favorite of the Prophet because of its chewy texture and flavor,” I said.

“The word ‘ajwah is a noun from the verb ‘aja. which means to pacify an infant who is still being breastfed, but who is in the process of being weaned,” Tahlawi explained. “It was a common practice among mothers in Arabia to use dates—especially the dry, chewy types, one of which is ‘ajwah—to wean their infants. They would let their babies chew on the date to pacify them, strengthen their gums and overcome their teething pains. Most likely, ‘ajwah got its name from this use, as it has the right texture and sweetness for the purpose.”

When I asked Tahlawi how he preferred to eat dates, he told me that he liked them as dessert after lunch or dinner, or one or two with a cup of Arabic coffee on special occasions.

It didn’t take long to realize that it is nearly impossible to get a consensus on the best variety from each region, but many people I talked to told me—and Tahlawi concurred—that any list of the best dates would certainly have to include these: nubout sayf, which is a long date shaped like a sword (sayf), from the Riyadh region on the Najd plateau in central Arabia; sukkari, meaning “sweet one,” from the Qasim region north of Riyadh; the rare (and very expensive) ‘anbar or ‘anbara date from the Madinah region; and finally, the khlas of al-Hasa.

Suspecting that certain dates are preferred over others at different stages of ripeness, I asked Tahlawi about the best stages to eat his favorite date varieties.

“Khalal, busr and saraban are different names, from different parts of the kingdom, for the date when it is almost fully grown but still green and unripe. My favorite date at this stage is the gharr, or ‘vigorous grower.’ Balah is the term for dates when they are fully grown and colored. My favorite dates at this stage are khlas, gharr and barhi. The rutab stage is when the dates are partially or fully ripened. Half or all of the date turns light brown and very soft. My favorites in this category are khlas, gharr and khunaizi. Tamr is the stage when all of the date turns dark brown and sticky with its sugary syrup. Khlas is an excellent tamr date. The last stage is called tamr yabis, or dry dates. At this point, the dates have turned dark brown, tough and lacking in dibs. Sukkari and hulayyah are my favorite tamr yabis dates.”

“What are dibs?” I asked.

“Dibs is a thick date syrup, similar to honey or molasses,” Tahlawi replied. “It comes from dates when they are fully ripened and then pressed. The khunaizi date from al-Qatif Oasis produces excellent dibs. Dibs has a sweet, acidic, slightly bitter flavor. It is used in making or covering sweets. Dibs is also an ingredient in a popular fish recipe called muhammar ma’ samak maqli, which translates as ‘brown or red rice with fried fish.’ In this dish, dibs is used to give the rice a brown color and a distinctive sweet and salty taste.”

he next day I drove south in search of the best khlas dates grown in the al-Hasa Oasis. Of the Arab world’s estimated 64 million date palms, some 14 million are in Saudi Arabia; of this number, more than three million grow in al-Hasa today. I spent the night in the city of Hofuf, and the following day I met Abdullatif Hamad Ali al-Salim, my driver and translator. On our way to the Al Hasa Bulk Date Factory, I asked him what he had eaten for breakfast. “Dibs mixed with tahinah and eaten with pieces of freshly baked pita bread. But sometimes I have five to eight dates with coffee or laban—or camel or goat milk,” he replied, adding that laban was similar to yoghurt.

he next day I drove south in search of the best khlas dates grown in the al-Hasa Oasis. Of the Arab world’s estimated 64 million date palms, some 14 million are in Saudi Arabia; of this number, more than three million grow in al-Hasa today. I spent the night in the city of Hofuf, and the following day I met Abdullatif Hamad Ali al-Salim, my driver and translator. On our way to the Al Hasa Bulk Date Factory, I asked him what he had eaten for breakfast. “Dibs mixed with tahinah and eaten with pieces of freshly baked pita bread. But sometimes I have five to eight dates with coffee or laban—or camel or goat milk,” he replied, adding that laban was similar to yoghurt.

At the factory, we watched endless conveyor belts laden with dates as they were hand-sorted by variety and then machine-washed and dried. Coming in from the groves, delivery trucks were backed up more than a kilometer, waiting to be unloaded. Many of these dates would be donated worldwide by the Saudi government as humanitarian aid and distributed through the United Nations World Food Program. In the office we sampled pitted dates dipped in chocolate, dates stuffed with almonds, dates covered in sesame seeds and dates rolled in coconut. We ate date toffee and tasted date sugar, machine-extracted dibs, puréed dates and date-filled pastries called ma‘moul—a favorite sweet during the ‘Id al-Fitr at the end of Ramadan. The samples were plentiful, but they did not represent the quality of dates that I was looking for. I wanted to find khlas dates that had been grown on small, family-owned farms, hand-picked, sorted and prepared in the traditional way.

|

|

|

|

| At the al-Hasa date market, wholesalers negotiate 60-kilo (132-lb.) marhalah baskets of khlas dates and other date varieties while trucks laden with hundreds more marhalahs (top) line up outside the Al-Hasa Bulk Date Factory. Mid-range and lesser quality dates are often donated to food relief charities worldwide: Saudi donations of dates in 2002 totaled nearly 800,000 metric tons. |

But our next stop was at the Date Palm Research Center. Because al-Hasa is the biggest producer of dates in the kingdom, the Center was established there by King Faisal University and the Ministry of Agriculture and Water in 1982. It carries out studies on cultivation, disease control, marketing, processing, quality control and the testing of new date varieties. At the Center, date farmers are taught how to incorporate newer horticultural techniques to complement what has been passed down to them by previous generations of growers.

The Center is an active member of the Arab National Committee for Date Palms, which, in turn, is part of the Arab Union for Food Industry. In recent years the Center has held several international scientific and business conferences to help study date growing and increase the production of fine dates. These gatherings have been attended by farmers, scientists, government officials, academics and others from around the world.

At the Center, Director Abdullatif Alkhateeb gave me a tour of the laboratory and the nursery. One of the most important research projects, he said, deals with tissue culturing, which creates large numbers of cloned seedlings from palms that produce large fruit of high quality.

“Traditionally, date palms are planted from offshoots that grow at the base of the palms. From planted offshoot to the first harvest usually takes seven years, and there is often a 50 percent mortality rate. In addition, planting from offshoots can pass on insect pests and diseases such as scale. What we do in the lab,” Alkhateeb explained, “is to take a very small cutting from the heart of the palm. This is the growth bud, which is located at the very top and center of the palm. A small piece of tissue from the heart of the palm is placed in a sterile solution of what looks like cloudy gelatin. It takes about 11 to 12 months for the embryo to grow to the point that we can cut it into pieces that all have the identical genetic makeup. From this point, it takes about three more months to grow each piece into an in vitro seedling. About six months later, the seedlings are unflasked and planted out. After that it will be an additional two to three years before the young palms flower. In the fourth or fifth year, the palms start producing fruit. Using the tissue-culture method, we have a negligible mortality rate, and the farmer gets his first crop two or three years earlier than if he had used the traditional offshoot method. Our tissue culture work is focused on the finest commercial dates such as khlas, hilali, um ruhaym, barhi, ruzaiz, and sukkari. A date palm typically produces good harvests for about 75 years, and this saving of time, using tissue culture, has been a tremendous benefit to local growers.”

The next day Abdullatif al-Salim drove me to the central wholesale date suq (market) in Hofuf. Out in the bright sun and stifling heat of mid-morning, dozens of pickup trucks and milling crowds of farmers and wholesale buyers went about the time-honored and boisterous task of buying and selling dates. I met with two elderly date tasters: ‘Abdul ‘Aziz al-‘Utaibi and Ibrahim al-Jawf. They sat in the shade of their warehouse and explained that the best khlas dates are large, with a firm texture, a pronounced yellow color, good translucence and complex flavor. Once these two men had made their selections, based on samples, the truckloads of dates were delivered to the huge, open-air processing area where teams of men washed them to remove dust and road dirt. The dates were then sun-dried for about 10 days. There were no conveyor belts to deal with the mountains of dates. Once dry, each date was carefully sorted by hand, and weighed into plastic bags that held five kilograms (11 lb) of dates. The plastic bags were stacked three high on a piece of burlap, then hand-stitched into a tight bundle. This 15-kilogram burlap bundle, known as a kees, is the standard unit of measure.

|

|

| A worker bags khlas dates in the packing shed at the al-Hasa date market. |

|

|

|

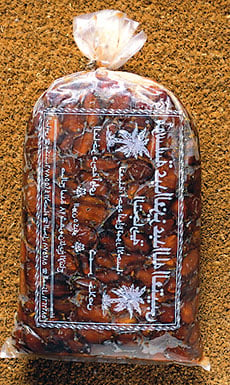

| A five-kilo (11-lb) bag of “Khlas Date First Class Supreme” from Al-Shaykh’s Nakhal Al-Rafi‘ah, “The Lofty Palm Grove.” |

At this point in the processing, the packaged dates are stacked on pallets and then pressed with concrete-block weights for at least one month. Al-Salim explained that this is to mature the dates, develop their flavor, produce dibs, improve the texture and color, prevent infestation of insects or worms and prolong shelf life. The dates are prepared this way so that they will last until the following year’s harvest, he said.

Before we left the date market I bought a five-kilo bag of khlas dates from ‘Abdul ‘Aziz al-‘Utaibi. I asked him to hand-select the very best dates he had. Back in the car, al-Salim turned on the air conditioning and sipped from a bottle of chilled water as I quietly congratulated myself on finding the best dates in the kingdom.

“So, Abdullatif,” I said, “after all of these days of searching and sampling dates, would you say these are some of the very best khlas dates in al-Hasa?”

“They are good, but I would not eat them or bring them to my family,” he replied.

“You wouldn’t eat them?” I said, thinking he was joking. “If these are not acceptable, then where does your family get dates?”

“We buy them freshly picked directly from a grower we know and trust, so we can handle each step of the preparation ourselves. It is a family tradition to spend several days preparing a supply of dates that will last us until the next harvest. In al-Hasa, each family has its own style of preparation. In my family, after washing and drying the dates, we lightly sprinkle them with aniseed or with toasted sesame seed. We sometimes use habit al-baraka [“blessed seeds,” Nigella sativa] for a special flavor.”

“Abdullatif, we have two days left before I must leave the kingdom. Where do we find a good grower?” I asked.

“It is the end of the season. I do not know anyone harvesting now, but if you really need to find the best, we must drive to al-Mutairfi. This area has the best khlas dates in al-Hasa.”

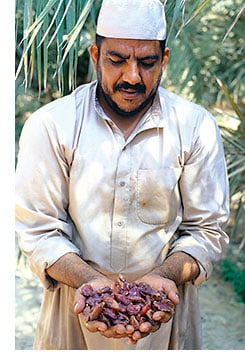

nd with that, we started our search all over again. Early the following morning, we were deep in the date groves of al-Mutairfi, searching for a grower who was still harvesting khlas dates. The confusing network of roads within al-Mutairfi is not signposted, and there are no numbers to identify individual properties. We drove up and down dusty dirt roads for hours, talking to the few people we saw, searching for fruit-bearing palms or the sight of trucks being loaded. Just after mid-day we found an open gate and a group of men crouched around a large pile of dates. We had arrived at Nakhal al-Rafi‘ah (“Lofty Palm Grove”), the property of Ahmad Hussain al-Shaykh, who was busy overseeing the very end of his khlas harvest. In two days he would be done. He was preoccupied, but when al-Salim told him we were looking for the very best khlas dates in al-Mutairfi, he quickly warmed to the topic.

nd with that, we started our search all over again. Early the following morning, we were deep in the date groves of al-Mutairfi, searching for a grower who was still harvesting khlas dates. The confusing network of roads within al-Mutairfi is not signposted, and there are no numbers to identify individual properties. We drove up and down dusty dirt roads for hours, talking to the few people we saw, searching for fruit-bearing palms or the sight of trucks being loaded. Just after mid-day we found an open gate and a group of men crouched around a large pile of dates. We had arrived at Nakhal al-Rafi‘ah (“Lofty Palm Grove”), the property of Ahmad Hussain al-Shaykh, who was busy overseeing the very end of his khlas harvest. In two days he would be done. He was preoccupied, but when al-Salim told him we were looking for the very best khlas dates in al-Mutairfi, he quickly warmed to the topic.

Al-Shaykh told us that discriminating customers from the Gulf states, Riyadh, Jiddah and elsewhere came to al-Hasa every year to buy dates. “Once they are in al-Hasa, they go to Hofuf, and from there all roads lead to the date groves of al-Mutairfi.” Al-Shaykh’s entire harvest is pre-sold to established customers who return year after year. The unit of measure for bulk sales is called a mann, equal to about 240 kilos, or 528 pounds; one mann of No. 1 khlas dates, direct from the farm, costs about 2000 riyals ($533); No. 2 khlas go for approximately 20 percent less. A big customer might buy up to 20 mann at a time.

Al-Shaykh gave us a brief tour of his date farm. Each palm annually yields anywhere from 60 to 100 kilograms (132–220 lb). He showed us a date palm climbing harness called karr, and the large, woven harvest baskets known as marhalahs, which hold approximately 60 kilos of dates. Al-Shaykh uses manure, mostly cow manure, to fertilize his palms, but he also enriches the soil by what he described as “burning the ground.” This is a very old technique, confined to the al-Hasa area, in which a shallow trench is filled with dead fronds, which are then covered with the excavated earth. The contents of the trench are set on fire, and later the burned earth and ash are spread beneath the palms.

We sat down for a mid-afternoon break in an open-air shed and drank lightly roasted coffee with freshly picked khlas dates. They tasted far better than anything I had tried in the previous week. Even al-Salim took notice.

I asked al-Shaykh if the quality of dates differed within a single grove. He said that the shade and irrigation in the center of a grove causes higher humidity, which makes the dates there develop a softer flesh and a slightly less complex taste. He thought the dates on the sunny southern edge of his property were more chewy and had a more concentrated flavor, thanks to the hot wind and additional sunlight. Before I could ask, al-Shaykh read my mind and sent a man to bring back some dates from those palms. Within 20 minutes we were eating dates that were even better than what had been laid before us earlier. They were indescribably delicious. I asked al-Shaykh if it would be fair to say that these khlas dates were the best examples from the best grove in the best growing region in the kingdom.

“It has been a good season in al-Mutairfi, but we are only one of several high-quality growers in this area,” he replied.

Despite this modest response, there was little doubt in my mind that we were eating dates of extraordinary quality. But when I asked al-Shaykh to be more specific, he said merely, “These are pretty good dates.”

Beneath the shade of the palms, I spotted a donkey tethered to a post. Remembering the saying about the earliest dates being suitable for the amir and the last ones for the donkey, I walked over to the animal. I held out my hand, palm up, and fed the donkey my last three California khalasahs.

|

Eric Hansen (ekhansen@ix.netcom.com) is an internationally known author, lecturer and photojournalist living in San Francisco. A specialist in the traditional cultures of Southeast Asia and the Middle East, he is a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World. |