ourteen years ago, Joseph Brincat, head of the Italian department at the University of Malta, brought to light the first known detailed text about the Arab conquest and settlement of his Mediterranean islands. The account appears in the 14th-century geographer Ibn ‘Abd al-Mun‘im al-Himyari’s Kitab al-Rawd al-Mi‘tar fi Khabar al-Aktar (The Perfumed Gardens), and it gives the names of both the Arab general who led the attack in AD 870 and the Byzantine ruler of Malta who was deposed.

ourteen years ago, Joseph Brincat, head of the Italian department at the University of Malta, brought to light the first known detailed text about the Arab conquest and settlement of his Mediterranean islands. The account appears in the 14th-century geographer Ibn ‘Abd al-Mun‘im al-Himyari’s Kitab al-Rawd al-Mi‘tar fi Khabar al-Aktar (The Perfumed Gardens), and it gives the names of both the Arab general who led the attack in AD 870 and the Byzantine ruler of Malta who was deposed.

Al-Himyari describes extensive destruction, and most historians believe the islands, whose position between Sicily and North Africa gives them strategic sway over trans-Mediterranean shipping, were left largely depopulated. The language spoken there—whether it was Punic, low Latin or Greek is still uncertain—was presumably supplanted by Arabic. What is known is that Arabic took firm hold in Malta in the mid-11th century, when Arabic-speaking colonists from Muslim Sicily began to arrive.

Though Arab rule in Malta lasted only until 1091, the conquering Normans allowed the Muslims to remain, and Arabic became their common language. More than a century later, in 1224, the Muslims were expelled, but their language—which had by that time evolved into a local Arabic dialect—remained, now cut off from the scholarly traditions of the mother language.

Though Arab rule in Malta lasted only until 1091, the conquering Normans allowed the Muslims to remain, and Arabic became their common language. More than a century later, in 1224, the Muslims were expelled, but their language—which had by that time evolved into a local Arabic dialect—remained, now cut off from the scholarly traditions of the mother language.

This was a major linguistic turning point. Arabic’s most striking linguistic dilemma—diglossia, or the difference between the written and the spoken languages—was moderated by the expulsion of the Muslims, but the event aggravated other problems, such as bilingualism, word mixing and code switching—the technical term for alternating between two languages in the same conversation. Scholars at the University of Malta, who are carrying out some of the world’s most advanced linguistic research, today find these problems fascinating.

Modern Maltese (or Malti, as the Maltese people themselves call their language) is described by some linguists as a “mixed language” of Semitic, Romance and English elements, while others simply call it an Arabic dialect. Maltese nationalists a hundred years ago portrayed Malti as related to ancient Punic; purists today fault the younger generation for adopting undigested loan words from English and Italian.

What is beyond dispute is that as of May 2004, when Malta joined the European Union, Malti became the eu’s only official language of Arabic origin. This leaves many Maltese simultaneously proud and worried about the cultural symbolism that their tongue holds in an ever-shrinking world.

The work of Oliver Friggieri, Malta’s leading fiction writer and poet, has been translated into Romanian, English, Bengali, Serbo-Croatian, Italian and, most recently, Arabic. “Maltese survives,” says Friggieri, “only because of its geographical position, halfway between speakers of Arabic and speakers of Romance languages. Our language gives us cohesion, and it will help us safely get through this ‘Eurofication’ process. Perhaps we can’t survive without English as our second language,” he continues, “but we will surely disappear without Maltese as our first.

“We Maltese have always outwitted our occupiers,” he says, referring to the succession of Normans, Angevins, Aragonese, Castilians, Knights of St. John, French and British who followed the Arabs, none of whom were ever able to impose their own language on the island. “Even Anglophones who move here pick up the intonations and rhythms of Maltese speech, something between Arabic and Italian.

“We Maltese have always outwitted our occupiers,” he says, referring to the succession of Normans, Angevins, Aragonese, Castilians, Knights of St. John, French and British who followed the Arabs, none of whom were ever able to impose their own language on the island. “Even Anglophones who move here pick up the intonations and rhythms of Maltese speech, something between Arabic and Italian.

“One way to outwit the occupier,” Friggieri explains, “is to be discreet when choosing between synonyms of Romance or Arabic origin. All things being equal, I prefer to use the Arabic-origin word, because it is usually so much richer and multi-dimensional. Even if my readers don’t have it on the tip of their tongues, they have it in their heads. I am very happy that my books are now in Cairo and Tunis—perhaps there they may find something of themselves in their shelf-mates.”

In the definitive Malti dictionary compiled by the late Joseph Aquilina, some 43 percent of the words have an Arabic origin, and roughly the same percentage claim Italian roots. Six percent come from English, and three percent come from Latin and the Romance languages.

Friggieri gives an example of two Maltese words: Both come from the same Sicilian stem, patire, and both mean “suffering”—though with very different connotations. Passjoni (the letter j in Malti is pronounced like a y in English) comes to Malti via Italian, and tbatija is “semiticized” thanks to Arabic’s high “productivity,” as a linguist would explain it. The term describes the ability of a base language to force loan words into its own morphology, grammar and syntax. Thus loan words such as patire are linguistically reshaped to conform to Arabic’s rules.

Friggieri gives an example of two Maltese words: Both come from the same Sicilian stem, patire, and both mean “suffering”—though with very different connotations. Passjoni (the letter j in Malti is pronounced like a y in English) comes to Malti via Italian, and tbatija is “semiticized” thanks to Arabic’s high “productivity,” as a linguist would explain it. The term describes the ability of a base language to force loan words into its own morphology, grammar and syntax. Thus loan words such as patire are linguistically reshaped to conform to Arabic’s rules.

In the case of tbatija, the original word patire has been reshaped according to the rules of Semitic verb formation. Tbatija today means “suffering” or “hurt” in general, while passjoni means specifically the suffering of Jesus. “But do not think that we Maltese use only Italianate words to express our Catholicism,” Friggieri warns. Randan, he points out, is Malti for the Christian season of Lent, and it comes from Ramadan, the Arabic name of the Islamic holy month of fasting. The word God, in Malti, is Alla.

Manwel Mifsud, of the university’s Maltese department, is a historical linguist specializing in word borrowing. “I started out by studying the Semitic side of Maltese,” he says, “believing I had to specialize in one side or the other. But I was most interested in the point where Arabic ended and Maltese began. I saw how Maltese’s Semitic morphology suffered from the stress of rapid word mixing and had almost reached a breaking point. It either had to heal itself, by adding new language tissue, or die out.”

A trend that he has identified in the case of Malti, and which may turn out to be something of a universal rule in other examples of language mixing worldwide, is that the base language’s productivity weakens over time, and also weakens whenever it faces a high rate of borrowing, as in the case of English technical terms that have flooded Malti in recent decades.

Mifsud’s research shows that there has been a long-term weakening trend in Arabic’s productivity in Malti. For example, a foreign word today is more likely to be absorbed into Malti as a stem plus a prefix and/or suffix, rather than, as in past, as an Arabic-style tri-consonantal root. Mifsud counts at least 36 loans from Romance languages that have gone through this transformation, from stem words into tri-consonantal roots, and which have generated, from that root, many other verb and noun forms with closely associated meanings.

Mifsud’s research shows that there has been a long-term weakening trend in Arabic’s productivity in Malti. For example, a foreign word today is more likely to be absorbed into Malti as a stem plus a prefix and/or suffix, rather than, as in past, as an Arabic-style tri-consonantal root. Mifsud counts at least 36 loans from Romance languages that have gone through this transformation, from stem words into tri-consonantal roots, and which have generated, from that root, many other verb and noun forms with closely associated meanings.

Mifsud gives the example of the English verb fire, in its military sense. Fire has become semiticized in Malti as fajjar, meaning “to throw violently,” which is a Semitic intensive verb form typified by its doubled middle consonant. Another example is pejjep, from the Italian pipa, meaning “to smoke.”

The verb jipparkjaw, meaning “they park [a car],” is a rare triple hybrid: The stem of the word, park, is an English verb. The initial p and the second j are Sicilian verbal additives, and the prefix ji and the suffix aw are Arabic verb formations that signal the present tense.

Loan nouns can be semiticized too, adopting what is called a “broken plural” form, in which the plural is formed not by adding a suffix—most commonly an s in English, as in singular brick and plural bricks—but rather by changing the internal structure of the word itself, like singular yowm (“day”) and plural ayyam (“days”) in Arabic. Maltese examples from Italian and English are pizza / pizaz; villa / vilel; skoona (“schooner”) / skejjen; and kitla (“kettle”) / ktieli.

The gradual loss of Arabic’s productivity in Maltese is evident in the way the modern loan word chips, in the collective plural British meaning of “French fries,” has entered Maltese in variant forms. Chips has acquired several suffixes, following both Italian and Arabic rules, to produce different derivative words: Chipsa means “one French fry,” following an Arabic rule for forming a singular; chipsata means “a lot of French fries,” following an Italian rule for forming an augmentative noun; and chipsiet, the counted plural of “French fries,” used after cardinal numbers, follows an Arabic rule for forming a sound (that is, non-broken) plural.

Mifsud has a lovely analogy for describing his language’s history. “I see Maltese as a prodigal son who has left home, that is, split away from the Arabic mother tongue, then learned many things from other peoples, that is, picked up Italian, French, English and Sicilian vocabulary words, and now, in his maturity, cannot find a way back to full reconciliation with his own brothers, that is, the other modern Arabic dialects.”

Martin Zammit teaches Arabic at the University of Malta and translated Friggieri’s collection Koranta and Other Short Stories From Malta into Arabic. Zammit became interested in Arabic as a youth, during the years that Malta’s former prime minister Dom Mintoff energetically engaged the Arab world and made Arabic a required language in Maltese secondary schools.

Martin Zammit teaches Arabic at the University of Malta and translated Friggieri’s collection Koranta and Other Short Stories From Malta into Arabic. Zammit became interested in Arabic as a youth, during the years that Malta’s former prime minister Dom Mintoff energetically engaged the Arab world and made Arabic a required language in Maltese secondary schools.

“Unfortunately,” says Zammit, “that policy backfired, because the level of instruction was so poor. Most high-schoolers from those years remember nothing of what they learned. Many sat in class just listening to Arab pop songs, and now they want nothing to do with Arabic.”

Zammit’s classes today are filled with far more motivated students, even if half of them are non-Maltese. “We still have a problem in this country convincing young people that Arabic should be part of their future,” he says. Of course, it does not help that the best first-year textbook for Arabic is written in English, translated from German. Zammit wishes there were a Maltese-based approach that could take advantage of the natural affinity of the two languages.

Of the four Maltese nationals in Zammit’s first-year Arabic class, two are classics majors with an interest in medieval history, one works for a shipping company with offices in Libya, and one is studying out of general interest. The foreign students—Armenian, Libyan–American, Palestinian, Dutch and German—also have mixed reasons for studying, but all are fully aware of where Malta is on the map: midway between North Africa and Europe.

Historical Malti has been a difficult topic to study because, until the 19th century, it was rarely written, and standard spellings were accepted less than a century ago. For years prior to that, linguists argued for and against the use of Arabic letters to capture the vestiges of Arabic phonetics in Malti that could not be represented in Latin script. Eventually, standard Latin letters were adopted, but with added diacriticals: a dotted g and z and a cross-stroked h. All early examples of written Malti employ idiosyncratic transcriptions and, in addition, all reflect the broad dialect differences between rural and urban areas and between the main island of Malta and its smaller sister island, Gozo.

The first documented Maltese text is a 20-line poem “The Cantilena” by Peter Caxaro, most likely written in the 1470’s. It came to light only in 1968, and linguists cannot agree if its language should be called an archaic form of Malti or a dialect of Arabic, for the only non-Arabic word found in the text is vintura, meaning “luck.” The text reads, “Min ibidill il miken ibidill il vintura,” or “He who changes his place changes his luck,” and this translates, word for word, a contemporaneous Sicilian proverb: “Cui muta locu muta vintura.”

The first documented Maltese text is a 20-line poem “The Cantilena” by Peter Caxaro, most likely written in the 1470’s. It came to light only in 1968, and linguists cannot agree if its language should be called an archaic form of Malti or a dialect of Arabic, for the only non-Arabic word found in the text is vintura, meaning “luck.” The text reads, “Min ibidill il miken ibidill il vintura,” or “He who changes his place changes his luck,” and this translates, word for word, a contemporaneous Sicilian proverb: “Cui muta locu muta vintura.”

Foreign visitors to Malta have long remarked on the sheer strangeness of the language. The apostle Paul was shipwrecked on the island in the year 60, and he called its inhabitants barbaroi, meaning that they spoke what was to him an unintelligible tongue. In 1663, Englishman Phillip Skippon noted that “the natives of the country speak little or no Italian but a kind of Arabick like that the Moors speak.”

In the mid-18th century, Maltese grammarian Agius de Soldanis transcribed verbatim dialogues between farmers who served as linguistic informants. These dialogues today seem to be in a language closer to an archaic Arabic than to modern Malti. That was only a few decades before Mikiel Anton Vassali compiled the first Malti–Italian– Latin lexicon, which identified five regional dialects on Malta and Gozo. His attempt at a standard Malti grammar was argued over for decades.

The problem of standardizing Malti is again a topic of debate in today’s Maltese parliament, where a national language bill is currently under discussion. It aims to take practical steps to cope with the overwhelming influx of loan words by easing their transition into reasonable Malti forms. “Otherwise,” says Mifsud, who is advising on this matter, “it will be a matter of ‘every man for himself’ whenever a new word is used. But we should only suggest, not sanction. We don’t want to be like the Académie française, imposing fines on writers for using an English word here or there.”

|

|

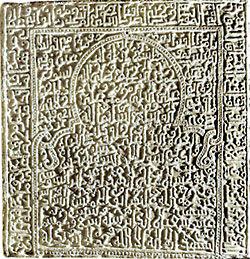

| This Arabic inscription, dedicated to “Maimuna” and carved in 1174 on Gozo, is one of Malta’s finest linguistic relics. It is now in Gozo’s Museum of Archeology. |

A visit to the island of Gozo today takes one back linguistically to far earlier times, though the ferry crossing takes only 20 minutes. The Gozitan dialect still grates on the ears of “big island” speakers of standard Malti, evoking for them a sense of isolated, rural backwardness. Gozitan Malti most strikingly maintains an emphatic h sound that is now lost on the main island, and it fully pronounces the letter q that elsewhere has become a glottal stop—a shift that, curiously, also happened in the Arabic of Cairo. Former president of Malta Ugo Mifsud Bonnici was a Gozitan, and his pronunciation on occasions of state always drew attention—sometimes unfavorable—to his roots.

It is on Gozo that one of Malta’s finest linguistic relics lies: An Arab tombstone dating to 1174, after the Norman conquest but before the Muslims’ expulsion. It is made from a reused piece of Roman marble, and its carving is in fine Kufic script. Found near the village of Xewkija (pronounced shaw-ki-ya, from the Arabic root for “thorn”), it commemorates a woman named Maimuna, the daughter of one Hassan ibn ‘Ali al-Hudali. It contains an Arabic poem in a meter called basit:

Look around you! Is anything everlasting on earth?

Anything that repels or casts a spell on death?

Death robbed me from a palace, and alas!

Neither doors nor bolts could save me.

All I did remains and shall be reckoned.

Native-born Gozitan Margaret Attard, a 60-year-old shopkeeper in the town of Xaghra (pronounced sha-ra, from the Arabic root for “hair”), remembers working on Malta as a young woman and always trying to hide her Gozitan dialect. “But when I came home on weekends,” she recalls, “I would very consciously revert to Gozitan, so I wouldn’t be taken as some cosmopolitan snob from ‘up there’”—as she still calls the main island.

Attard knows that her language is close to Arabic—so close, in fact, that she has been mistaken for an Arab while visiting Italy. Unlike the many Maltese who still deny their language’s debt to Arabic, Attard readily acknowledges its linguistic contribution to her island’s history, and sometimes even errs in its favor. “My name comes from the Arabic word ‘attar, meaning ‘scentmaker,’” she says—though in fact it more likely comes from the Sicilian surname Attardo.

Palestinian– Maltese businessman Hani Abdalla has lived in Malta for 25 years. His wife is Maltese, and his children speak Malti. He feels fully fluent in his adopted language. “I learned quickly. I’d say I spoke with 90-percent fluency after just two years,” he says, noting how easy it is for educated Arabs to guess the meaning of many Malti words, even those originating from an archaic Arabic root long disused in modern colloquial Arabic.

Palestinian– Maltese businessman Hani Abdalla has lived in Malta for 25 years. His wife is Maltese, and his children speak Malti. He feels fully fluent in his adopted language. “I learned quickly. I’d say I spoke with 90-percent fluency after just two years,” he says, noting how easy it is for educated Arabs to guess the meaning of many Malti words, even those originating from an archaic Arabic root long disused in modern colloquial Arabic.

In fact, he adds, he feels more at home in Malti than he would speaking an Arabic dialect not his own. For instance, the word for “now” in both Maltese and Palestinian Arabic is issaa, from the Arabic root saa’a, meaning “hour.” In Egyptian Arabic the word for “now” is dilwaqti, and in Yemeni Arabic it is al-aan. The generic term in Malti for a very old man is xay akka, from the Arabic Shaykh Akka—“an elder from Acre,” the city on the Mediterranean coast just 50 kilometers (30 mi) from Abdalla’s birthplace in Jenin.

But sometimes Abdalla, like Attard, can be too quick to presume an Arabic root where there isn’t one. “I always thought the Maltese adverb bilmod, meaning ‘slowly,’ was a composite word combining the Arabic preposition bi with the definite particle and noun al-mawt, meaning ‘with death.’ I presumed that in Maltese this meant something like ‘as slow as death.’ But just recently I learned that it comes from the Italian modo meaning ‘manner,’ but still with the Arabic preposition.”

Abdalla’s close friend Zammit, whom he is helping to interpret the Qur’an into Malti, notes how Arabic words and Islamic expressions have often entered Malti and taken on specifically Christian meanings. “Take the archaic Malti word gilwa,” he says. “For us it means ‘a church wedding procession,’ but in fact it derives from the Arabic verb jalaa, meaning ‘to unveil’ or ‘to reveal,’ referring to the moment in a Muslim wedding when the bride uncovers her face to her husband.”

In the old town of Mdina—a name originating in the Arabic word for “city,” madinah—Zammit notes that people every day walk along Triq Miskita, a street name that comes from the Arabic tariq (“way”) and the Spanish mesquita (“mosque”), though they may be unaware that a mosque once stood on that street. “And our proverb ‘minn fommok ghal Alla,’ meaning ‘from your mouth to God,’” says Zammit, “is borrowed word for word from the same proverb in Arabic.”

The Maltese people are slowly coming to terms with this legacy. Manwel Mifsud notes a bit of envy among fellow Arabic dialectologists when they meet in international conferences. “They somehow wish that ‘their’ dialect, the one they specialize in, had been able to grow into a separate language of its own as Malti has! They think it adds prestige.”

Arnold Cassola, professor of Maltese at the University of Malta and currently on leave in Brussels as secretary-general of the European Federation of Green Parties, has a special perspective on Malti’s mixed parentage and the advantages it conveys in the European Union. “Within my own family tree are German, Arab, British and Italian surnames,” he says. “Malta, as a nation-state within the EU, reflects the EU’s own unity and diversity.” Because of this cultural openness, Cassola thinks Malta is the natural European interlocutor with Arab countries on matters of trade and refugee protection.

Cassola’s academic research showed how Malti, spoken by only 17,000 natives in 1530, survived following the establishment there of the Knights of St. John, who arrived that year 3000 strong and who were followed by wave after wave of Siculo-Italian immigrant laborers. Because the knights divided themselves into eight “langues,” or national suborders, each speaking its own tongue, Malti benefited from the “divide and conquer” principle: Faced with eight new languages, it remained the unifier, the lingua franca.

Cassola’s academic research showed how Malti, spoken by only 17,000 natives in 1530, survived following the establishment there of the Knights of St. John, who arrived that year 3000 strong and who were followed by wave after wave of Siculo-Italian immigrant laborers. Because the knights divided themselves into eight “langues,” or national suborders, each speaking its own tongue, Malti benefited from the “divide and conquer” principle: Faced with eight new languages, it remained the unifier, the lingua franca.

The knights themselves used Malti to carry out their duties. In 1987, Cassola discovered an anonymous Malti grammar and wordlist, probably dating from the late 17th century, one chapter of which is titled in mixed Maltese and French: Lta‘lim a’l Soldat: Methode pour Faire l’Exercise des Armes en Langue Maltoise (The Instruction of Soldiers: How to Carry Out the Manual of Arms in the Maltese Language). The text had evidently been compiled by the knights to give native speakers military training or to teach the knights the local military vocabulary.

Some of the earliest Malti texts were composed for purposes of translation and cultural liaison, notes Cassola—and he sees a foreshadowing in that. “The fact,” he says, “that under EU rules, the same number of official translators and interpreters is guaranteed for Maltese as for German and French can only increase our linguistic pride.” Even though Malta will not fill all those positions immediately, he is certain that Maltese delegates will fill the European Parliament with the sounds of Europe’s only Semitic language.

“We have a saying,” chuckles Cassola: “‘Tkellem bil-malti jekk tridni nifhmek,’ or ‘Speak Maltese if you want us to understand you.’ And every word of that proverb is of Arabic origin.”

|

Louis Werner is a filmmaker and free-lance writer living in New York. He can be reached at wernerworks@msn.com. |

|

Alan Calleja is a free-lance photographer based in Valetta, Malta. |