|

|

|

| Aske, 85, is one of the most renowned hunters in the Altai region. He holds a newly caught, hooded eagle to whose legs he has attached iakbo (jesses). Training it will take about three weeks. If it proves a good hunter, Aske will keep it—but for no more than 10 seasons before releasing it to the wild. |

|

|

olden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) live throughout the northern hemisphere, inhabiting open and semi-open habitats including tundra, shrublands, grasslands, woodland, brush land and coniferous forests from sea level to 3600 meters’ (11,700') elevation. Most are found in mountainous areas, but they also nest in wetland, river bottoms and estuaries. With a height from head to tail of up to a meter (39"), a wingspan of two meters or slightly more (80") and an average weight of three to seven kilograms (7–15 lb), they are one of the world’s largest predatory birds. They can dive at speeds up to 280 kph (175 mph). Members of the “booted eagle” family, their legs are feathered down to the talons. They are non-migratory, monogamous and live an estimated 35 years in the wild. Their diet is composed primarily of small mammals, including rabbits, hares, marmots and young deer. Their endangered status varies by region. Conservation efforts have been focused on Central Europe, where extensive hunting in the 19th century has confined the remaining population to the Alps. olden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) live throughout the northern hemisphere, inhabiting open and semi-open habitats including tundra, shrublands, grasslands, woodland, brush land and coniferous forests from sea level to 3600 meters’ (11,700') elevation. Most are found in mountainous areas, but they also nest in wetland, river bottoms and estuaries. With a height from head to tail of up to a meter (39"), a wingspan of two meters or slightly more (80") and an average weight of three to seven kilograms (7–15 lb), they are one of the world’s largest predatory birds. They can dive at speeds up to 280 kph (175 mph). Members of the “booted eagle” family, their legs are feathered down to the talons. They are non-migratory, monogamous and live an estimated 35 years in the wild. Their diet is composed primarily of small mammals, including rabbits, hares, marmots and young deer. Their endangered status varies by region. Conservation efforts have been focused on Central Europe, where extensive hunting in the 19th century has confined the remaining population to the Alps. |

|

| map: Phillip Engelhorn |

ntil a decade ago,

falconers around the globe lamented that Central Asian countries barred them from contact with the founding fathers of their sport. The political curtain has now been drawn aside, but nonetheless, so chilly are the winters and so remote the hunters’ homes that few people witness eagle hunting in its original context. Last winter, photographer Philipp Engelhorn and I donned all

the polar fleeces we could muster and headed out to China’s Xinjiang Province. Despite our background research, we did not imagine we’d face temperatures as low as -40°, or roads covered with more than a meter (3') of snow and navigable only by horse-drawn sleigh.

ntil a decade ago,

falconers around the globe lamented that Central Asian countries barred them from contact with the founding fathers of their sport. The political curtain has now been drawn aside, but nonetheless, so chilly are the winters and so remote the hunters’ homes that few people witness eagle hunting in its original context. Last winter, photographer Philipp Engelhorn and I donned all

the polar fleeces we could muster and headed out to China’s Xinjiang Province. Despite our background research, we did not imagine we’d face temperatures as low as -40°, or roads covered with more than a meter (3') of snow and navigable only by horse-drawn sleigh.

At the northernmost point of Xinjiang is Friendship Peak, the summit where the borders of Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and China all meet, dividing the scattered populations of Kazakh people, who for millennia ranged freely with their herds. Today, an estimated 11 million Kazakhs are divided among these four countries and Uzbekistan to the west. Eight million live in Kazakhstan, and the largest population after that is the 1.4 million in Xinjiang Province. Most of Xinjiang’s Kazakhs owe their Chinese

citizenship to Russian agrarian reforms of the early 20th

century, which they evaded

by fleeing eastward into what

was then not clearly defined

as Chinese territory.

Scholars at the Peregrine Fund’s Archives of American Falconry in Boise, Idaho believe that the practice of hunting with birds of prey originated among nomadic tribes in Central Asia around 6000 years ago. Among the scarce records are Hittite pottery shards that suggest that falconry was a custom of royalty on the Anatolian Peninsula as early as 4000 years ago. Tang Dynasty paintings depict falconry as having come into China from the north only in the seventh century of our era. In the 12th century, Genghis Khan’s bodyguards were allegedly selected from an elite regiment

of falconers, and his grandson Qubilay Khan hosted extravagant falconing expeditions that were described by Marco Polo. Though falconry was well known to both Europeans and Arabs from very early times, both groups adopted it as a sport only after the 13th century, after the Mongolian invasions and the Crusades.

For Kazakhs, hunting with eagles is one of the highest expressions of their cultural heritage. Though rabbits, marmots and owls are hunted too, it’s the corsac fox, with its

reddish, highly insulating fur, that is the most prized quarry. A fox pelt can fetch 200 Chinese yuan ($24) on the black market, but the idea of such commerce is regarded by most hunters as laughable at best, or an insult. With an eagle’s meals amounting to half a

kilo (17 oz) of washed meat

a day, in addition to all of the demanding preparation of the necessary dietary supplements, hunting with an eagle “is certainly not for economic gain,” as one hunter asserted with pride. Instead, it is an art,

a sport of refinement that involves a great deal of time and the use of sophisticated tools and techniques that have been passed on from father to son for millennia. It requires

a combination of strength and gentleness and a reverence for the natural world—and, above all else, what Kazakhs regard as a valiant spirit that exemplifies ideals of honor and manhood. Even in cities today, young men boast of the accomplishments of Aske, the region’s most celebrated eagler: “Seventy foxes a season!” we were told by more than one aficionado.

For Kazakhs, hunting with eagles is one of the highest expressions of their cultural heritage. Though rabbits, marmots and owls are hunted too, it’s the corsac fox, with its

reddish, highly insulating fur, that is the most prized quarry. A fox pelt can fetch 200 Chinese yuan ($24) on the black market, but the idea of such commerce is regarded by most hunters as laughable at best, or an insult. With an eagle’s meals amounting to half a

kilo (17 oz) of washed meat

a day, in addition to all of the demanding preparation of the necessary dietary supplements, hunting with an eagle “is certainly not for economic gain,” as one hunter asserted with pride. Instead, it is an art,

a sport of refinement that involves a great deal of time and the use of sophisticated tools and techniques that have been passed on from father to son for millennia. It requires

a combination of strength and gentleness and a reverence for the natural world—and, above all else, what Kazakhs regard as a valiant spirit that exemplifies ideals of honor and manhood. Even in cities today, young men boast of the accomplishments of Aske, the region’s most celebrated eagler: “Seventy foxes a season!” we were told by more than one aficionado.

Aske, who like many in the region goes by a single name, lives in the Jungarian Basin south of the Altai Mountains. At 85, he carries the title batur, or warrior-hero, earned for his exploits fighting alongside the Soviets at Stalingrad in 1942 and 1943. We arrived in his village after one day in a jeep—more shoveling than driving—and a second day traveling by horse and sleigh.

Hours later, the old batur came riding home. A wooden crutch attached to his saddle supported his right arm; on that arm perched a golden eagle, blinded by a fitted leather hood. Under his left arm was a second eagle, hooded too and wrapped in a blanket. He had caught the second one while out hunting that afternoon. Spotting it flying over

the hills, he had laid out a net baited with fresh rabbit meat and waited for it to come feed and entangle itself.

Two months had passed since he had invited us to visit during the hunting season, but our presence earned only a nod of acknowledgment as he hastily brushed by us with

his new bird and beckoned us into his adobe home.

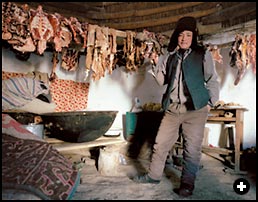

Inside, pelts hung like trophies on the carpeted walls. Aske wasted no time evaluating his new bird. He stood it on his gloved forearm and rolled his forearm back and forth to test the bird’s balance. He felt its upper legs for muscle mass and stretched out each of its talons over the glove. Then he slipped off the leather hood and poised his hand in front of the eagle’s beak, nimbly dodging pecks before snapping the beak shut. He slipped the hood back over the eagle’s head and finally turned to us with his assessment.

|

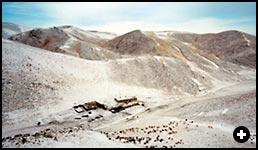

| Above: Many eagle hunters earn their livelihoods by herding and ranching. This compound lies near China’s border with Kazakhstan, between the Jungarian Basin and the Saur Range, the northernmost peaks of the Tian Shan Mountains. Below: In the remote and snowy territory of the eagle hunters, a horse-drawn sleigh is often the best way to get around. |

|

“It’s a fine eagle. In three weeks it will be ready to hunt. It’s scared now, but once it’s used to human voices, it will

get feistier.” He counted the tail feathers and inspected the white specks on its wings to estimate the eagle’s age. “It’s six, a good age.” The Kazakh language has a specific term for each of the first seven years of an eagle’s life. Although they may live past 30, eagles caught in their first seven years are thought to make particularly loyal partners. Females,

as the larger and stronger of the sexes, are preferred. But a bird’s potential depends also on its individual temperament. One hunter told us he might catch 10 to 15 eagles before finding one that would be worth training.

Aske, together with his new eagle, spent that evening watching a television program on sub-Saharan wildlife, the dubbed Kazakh soundtrack blasting to compensate for Aske’s deaf right ear. The eagle perched on his arm throughout as

he mechanically went through the training routine of hooding and unhooding it, rolling his forearm back and forth, back and forth.

or all his hospitality, it turned out that Aske guarded his secrets more closely than we—or perhaps he himself—had expected. One morning, Philipp and

I found him consulting a few dozen corn kernels

that he had rolled like dice onto a table. Was this a Kazakh folk tradition or just one man’s idiosyncrasy? Aske analyzed the design, and then he looked up to relate what it meant. “Tomorrow I must leave the village. You should stay here a day or two and then be on your way.” I pressed him to take us hunting before he left: We had come so far to witness his skill! He replied by pointing to our western hiking boots and then slapping the shaft of his own stout, knee-high, black leather boots, imported from Kazakhstan. He shook his head: He feared the government would hold him responsible for our frost-bitten limbs.

or all his hospitality, it turned out that Aske guarded his secrets more closely than we—or perhaps he himself—had expected. One morning, Philipp and

I found him consulting a few dozen corn kernels

that he had rolled like dice onto a table. Was this a Kazakh folk tradition or just one man’s idiosyncrasy? Aske analyzed the design, and then he looked up to relate what it meant. “Tomorrow I must leave the village. You should stay here a day or two and then be on your way.” I pressed him to take us hunting before he left: We had come so far to witness his skill! He replied by pointing to our western hiking boots and then slapping the shaft of his own stout, knee-high, black leather boots, imported from Kazakhstan. He shook his head: He feared the government would hold him responsible for our frost-bitten limbs.

It was in fact astonishingly cold outside as we set out

to find another hunter. On sleighs we zigzagged across the region from settlement to settlement through blizzards so dense that sky and earth were indistinguishable. We navigated by word of mouth, interviewing hunters and watching them parade their birds, determined to find an eagle hunter whose expertise would match Aske’s. We sat around hearths and listened to men tell their tales. For many of them, though, these tales seemed to be all they had: Overgrazing of the rangelands, due to increased herd sizes, has diminished wildlife populations in recent decades. The corsac fox is waning, especially in the prairies of the Jungarian Basin, and though

it is not endangered (see “The Corsac Fox,” page 18), it is increasingly scarce. Eagles that

a decade ago would have had a busy hunting season now sit idle in a corner of the hunter’s house.

|

| Above: A hunter adjusts the cuff of one of the jesses (iakbo) so that it will fit the eagle’s leg without chafing. Below: Each autumn, a hunter sets aside a day to slaughter the meat that will feed the eagle through the winter season. It often includes mutton, beef and, on occasion, horse. The meat is hung and dried in a clean, unheated room. |

|

n the middle of the Jungarian Basin, in a village of 30 or so houses, we found Hadrola, a veterinarian and a family man. His eagle is kept busy despite the scarcity of foxes. “The neighbors laugh at me,” he confessed. “They say, ‘He goes out with his eagle all day and comes home with nothing.’ Well, let me tell you, I don’t care if I catch a fox or not! I have to take my eagle out every day, even if it’s only for an hour. The wilderness, the sky, the snow and the eagle flying above—for me, it’s like traveling. It’s like a holiday!”

n the middle of the Jungarian Basin, in a village of 30 or so houses, we found Hadrola, a veterinarian and a family man. His eagle is kept busy despite the scarcity of foxes. “The neighbors laugh at me,” he confessed. “They say, ‘He goes out with his eagle all day and comes home with nothing.’ Well, let me tell you, I don’t care if I catch a fox or not! I have to take my eagle out every day, even if it’s only for an hour. The wilderness, the sky, the snow and the eagle flying above—for me, it’s like traveling. It’s like a holiday!”

Hadrola’s eagle is treated more like a pampered child than a pet. In the morning he feeds it water through a reed straw from his own mouth. At night he massages the bird’s plumage as it dozes off in the vestibule. With the bird sound asleep and a grandson bouncing on his knee, the 45-year-old narrated foxhunts from his boyhood, when he went out with his uncle. Today, deprived so often of the object of the sport, Hadrola and those like him pay more attention to its esthetics.

The Chinese government’s policies on eagle hunting are

a matter of constant discussion and, for the hunters, annoyance. On the one hand, the tradition is officially hailed as a “minority nationality custom”; the prefectural government thus coordinates official eagle-hunting festivals, and state-owned television airs documentaries of Kazakhs in traditional garb atop picturesque peaks with their birds on their arms. On the other hand, hunting with eagles, or by any other means, has been officially outlawed since the 1980’s. On the one hand again, the ban was not enforced. On the other hand again, with the recent rise of pressure to develop the region for ecotourism, wildlife preservation has acquired a new urgency, and since about 1999, enforcement has begun: Hunters have been fined, furs have been confiscated, and eagles forcibly released to the wild. Along the newly completed summer-tourist roads, we arrived at many a hunter’s door only to find that authorities from the Bureau of Forest Resources had recently

been there, demanding to watch

the eagle set free.

The conservation concerns are real. Under Chinese dominion, the population of Xinjiang Province has increased fourfold since 1949, and livestock numbers have risen proportionately. The strain on ecologically fragile rangelands has sent the corsac fox into decline. The bigger

picture, however, may not be

so grave. The species is naturally prone to dramatic population fluctuations, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (UICN) ranks the corsac fox in

the category of “least concern” on the 2004 Red List of Threatened Species. The golden eagle, however, which is found throughout the northern hemisphere, is generally regarded as endangered in China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan.

The conservation concerns are real. Under Chinese dominion, the population of Xinjiang Province has increased fourfold since 1949, and livestock numbers have risen proportionately. The strain on ecologically fragile rangelands has sent the corsac fox into decline. The bigger

picture, however, may not be

so grave. The species is naturally prone to dramatic population fluctuations, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (UICN) ranks the corsac fox in

the category of “least concern” on the 2004 Red List of Threatened Species. The golden eagle, however, which is found throughout the northern hemisphere, is generally regarded as endangered in China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan.

|

|

orsac foxes (Vulpes corsac) are found across the steppe and semiarid regions of inner Asia from Iran and Kazakhstan in the west to China and Mongolia in the east. Weighing up to 4 kilograms (10 lb), an individual’s body and tail together often measure about a meter (39'') in length. Corsacs are more social than most fox species, and live in pairs or small packs. They have no attachment to territory, however, and den temporarily in caves and the burrows of rabbits and marmots, which they enlarge. Corsac foxes appear to depend on the distribution of ground squirrels and marmots for both food and shelter. They feed on smaller mammals, reptiles and birds. Though farming and livestock husbandry have significantly reduced their range, the IUCN’s 2004 Red List of Threatened Species ranks Vulpes corsac in the category of “least concern.” “Corsac populations fluctuate significantly,” the iucn writes. “Population decreases are dramatic, caused by catastrophic climatic events, and numbers can drop tenfold within the space of a single year. On the other hand, in favorable years numbers can increase by the same margin and more within a three to four year period.” orsac foxes (Vulpes corsac) are found across the steppe and semiarid regions of inner Asia from Iran and Kazakhstan in the west to China and Mongolia in the east. Weighing up to 4 kilograms (10 lb), an individual’s body and tail together often measure about a meter (39'') in length. Corsacs are more social than most fox species, and live in pairs or small packs. They have no attachment to territory, however, and den temporarily in caves and the burrows of rabbits and marmots, which they enlarge. Corsac foxes appear to depend on the distribution of ground squirrels and marmots for both food and shelter. They feed on smaller mammals, reptiles and birds. Though farming and livestock husbandry have significantly reduced their range, the IUCN’s 2004 Red List of Threatened Species ranks Vulpes corsac in the category of “least concern.” “Corsac populations fluctuate significantly,” the iucn writes. “Population decreases are dramatic, caused by catastrophic climatic events, and numbers can drop tenfold within the space of a single year. On the other hand, in favorable years numbers can increase by the same margin and more within a three to four year period.” |

Hunters argue that such environmental awareness is in fact an integral part of their sport. Kazakhs across the Altai region close the hunting season on their own on the 20th of February, a date chosen to allow female foxes to gestate and raise their kits in peace. As for the golden eagles, custom mandates that, after 10 seasons in captivity, an eagle must be released to breed in the wild. The eaglers see themselves as part of the steppe’s ecological equilibrium.

Policies of neighboring Kazakhstan and the Kazakh-populated Bayan-Ölgiy Province of Mongolia have been quicker to recognize this. Those governments have encouraged hunters to

set up tourist agencies that offer eagle-hunting outings to foreign visitors, and already there are dozens in Mongolia alone. In 2000, the United Nations began funding a three-year environmental education program in Kazakhstan aimed at preserving both hunting and eagle populations with a museum and sanctuary.

In areas still more remote, far off even the most lightly beaten tracks, there are pockets where things still operate fairly traditionally. In one such area, some 90 kilometers (50 mi) from the Kazakhstan border, lies the house of Kenjahan, an isolated outpost in the northernmost Saur Range of the Tian Shan mountains.

utside Kenjahan’s front door, two wolves circle the posts to which they are chained. A small solar panel dangles off the south side of the roof. A police officer has led us here: A friend of a friend we’d met at a wedding, he was so enthusiastic about our project that he insisted on driving us himself to meet this regional champion, a trip of four hours by four-wheel-drive across the icy, roadless mountains.

utside Kenjahan’s front door, two wolves circle the posts to which they are chained. A small solar panel dangles off the south side of the roof. A police officer has led us here: A friend of a friend we’d met at a wedding, he was so enthusiastic about our project that he insisted on driving us himself to meet this regional champion, a trip of four hours by four-wheel-drive across the icy, roadless mountains.

In 1962, Kenjahan told us, he began hunting bears and wolves to protect the nearby coal-mining commune. Now 63, he spoke nostalgically of the days when his hunting statistics were broadcast over Xinjiang radio in the name of the socialist cause. No man we had met commanded his eagle with the precision of this occupational hunter—not even Aske.

“If four men place their four eagles on a mountaintop and go down to the valley to call them, then each eagle will fly to the arm of its master. An eagle knows its master,” he said. His certainly did: He set the eagle on the mountainside, and it skimmed over the surface up to the crest, where it caught the wind and floated a hundred meters above us. When Kenjahan wanted the bird to come down, he held out a piece of rabbit meat and called “Ay! Ay!” The eagle promptly tucked its wings for a direct descent to its master’s arm.

|

|

|

| Left: “When you let the eagle go, she won’t fly away,” says one eagler. “She moves with you, overhead in the sky.” Although the eagle can spot foxes from great distances against the snow, the fox’s reddish-sandy coat allows it to elude the eagle when there is no snow cover. Right: At the moment of the strike, the eagle’s wide-open talons clench, penetrating the fox’s heart and killing it instantly. Typically, the eagle will then half-fold its wings over its prey, a behavior called “mantling.” The hunter immediately distracts the eagle with a bit of meat. |

|

| Above: A hunter’s entire family is often well-outfitted with coats and vests lined with corsac-fox fur. Below: Deep-fried dough and butter tea have sustained many an eagle hunter through a cold winter on the steppe. |

|

Man and eagle moved in unison, and on our hunting

day with him we found again the luck that for weeks had seemed to run against us. A fox came darting out from a rock crevice. In a single gesture, Kenjahan unhooded the bird, swung out his arm and sent the eagle into the air. Responding immediately, it swooped down the incline toward the red blur and thrust out its taloned feet. One locked onto the fox’s neck, the other its lower back, and the eagle’s momentum dragged it a few meters over the snow before touching down. Kenjahan followed full speed down the hill and arrived just as the eagle was mantling its kill under its wings. Kenjahan held out a piece of meat and the bird’s attention shifted. It moved off the quarry and onto its master’s arm with a seemingly happy hop that contrasted with the ruthlessly efficient predation we just had witnessed. Kenjahan looked up at our awestruck expressions and laughed heartily.

In one afternoon, this man had shown us what we’d spent

a month looking for. And now, with his three sons riding behind him, the fox swinging from his saddle and the hovering eagle overhead his shadow in the sky, Kenjahan rode confidently toward home. A proverb we’d heard many times had never seemed so finely embodied as

in that moment: “Fine horses and fierce eagles are the wings

of the Kazakhs.”

Aske and Kenjahan may be from different generations, but to young men today they are both from a waning breed of Kazakhs whose pride, independence and stoicism generated an air of nobility so rich that the material poverty of their circumstances seemed to vanish. There were small-time sport hunters who regarded the tradition as a poor man’s luxury, and then there were men like these, the living chronicles of a nomadic heritage. “Eagle hunting has been in my family for hundreds of years,” Kenjahan said. But the inverse seemed no less true: The spirits of his ancestors live on through the eagle.

|

|

TOMAGA: The hood that blinds the eagle, this is the most emblematic trapping. Depriving the eagle of its keenest sense is the basis of its domestication, and a tomaga is put on an eagle as soon as it is caught. The tomaga is constructed by pattern from a single piece of cowhide and modified to fit the head of each individual bird, so it does not leak light and cannot be shaken off. |

|

TORR: A hand-knotted twine net used to catch eagles, baited with fresh meat in the dead of winter. With an eagle entangled in the net, the hunter can easily subdue it. |

|

BIALEYE: This is the protective cowhide mitten that a hunter wears on his right hand and forearm whenever he’s handling the eagle. |

|

IAKBO: These are the jesses, the leather straps attached to the eagle’s legs. They are padded with felt to reduce chafing and worn at all times. In flight, they dangle from the legs. The iakbo attach through metal rings to a leash to allow a quick release during the hunt. When the eagle is sitting on his forearm, the hunter clamps the iakbo under his thumb to prevent the bird from moving. |

|

JIMDORBA: A stash of rabbit or marmot meat is kept on hand in this special purse worn by the hunter. Meat has to be readily accessible because it is used to control the bird and lure it quickly away from the quarry to prevent damage to the pelt. |

|

BALDACH: The crutch, mounted against the side of the saddle, that props up the hunter’s forearm as he carries his eagle. Pursuing a fox can take a hunter away from home for days, and he will rely on the hospitality of other hunters in the region for food and shelter. But with a bird perched on his arm, a hunter would not get far without the baldach. |

|

TOGHORR: When inside or outside the house, the eagle spends its time perched on this three-legged stool, to which the jesses are tied. |

|

SAPDIAK: In every hunter’s kitchen is this almond-shaped wooden bowl used specifically for hand-feeding an eagle. During the hunting season, an eagle is fed less, to encourage voracity and keep it in shape. Preparing a meal is a laborious process: The hunter must cut the meat into strips and soak them in the sapdiak to wash out the blood. Bloody meat allegedly makes an eagle lethargic, intractable and harder to lure off a fresh kill. |

|

HOYA: Once a week at mealtime, a hunter force-feeds the eagle this digestive enhancer, typically made from the down of cattails wound together with thread into a 10-centimeter (4") pellet. It substitutes for the bits of fur that an eagle would consume in the wild, and it absorbs harmful fat from the digestive track. The next day the eagle coughs up the hoya as it would a casting in the wild. |

|

TOMACH: The single most telltale sign that someone has an eagle hunter in the family is the tomach, the fox-fur hat worn as a symbol of status by men over 60 years old. These elders joke that young men are just too thick-haired and hot-headed to endure the insulating fur of the tomach—try it, they say, and you’ll suffer headaches! |

| |

IRON TRAPS: A hunter’s sons are often in charge of monitoring the traps laid for rabbits, marmots and rodents in the immediate vicinity of a hunter’s home. These traps supply the meat required daily to maintain a strong and well-trained eagle. “If all we wanted was to catch a fox, we’d just use a trap—traps don’t fuss so much,” one hunter joked. |

|

Rebecca Schultz is a free-lance writer focusing on the Muslim cultures of interior Asia and China. She works in Washington, D.C. in international development. |

|

Philipp Engelhorn is a free-lance photographer living in Hong Kong. He can be reached at www.philippengelhorn.com. |