Written and photographed by Charles O. Cecil

|

| Though some gum will flow naturally from cracks in the bark of the Acacia senegal tree, commercial tappers stimulate the flow by removing thin strips of bark, an operation that requires some skill if the tree is not to be injured. Tapping is normally done once a year starting in October, the end of the rainy season in Niger. Gum collection begins about four weeks after stripping, and can be repeated every few weeks thereafter for several months. Most trees yield gum for about 10 years. |

Gum arabic can be almost completely dissolved in its own volume of water—a very unusual characteristic. I added the resulting solution to the pancake syrup, and in less than half a minute, the sugar crystals dissolved.

Gum arabic is the hardened sap of the Acacia senegal tree, which is found in the swath of arid lands extending from Senegal on the west coast of Africa all the way to Pakistan and India. Just as Arabic numerals acquired their name because Europeans learned of them from the Arabs—who had picked them up from India—so too do we owe the name of gum arabic not so much to its origins, but to Europe’s early trading contacts with the Middle East.

According to Sudanese sources, gum arabic was an article of commerce as early as the 12th century BC. It was collected in Nubia and exported north to Egypt for use in the preparation of inks, watercolors and dyes. Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, mentions its use in embalming in Egypt. In the ninth century of our era, the Arab physician Abu Zayd Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi, writing in his Ten Treatises on the Eye, described gum arabic as an ingredient in poultices or eye compresses.

By the Middle Ages, gum arabic was valued in Europe among scribes and illustrators. Following the gilding of letters in illuminated manuscripts, the application of color was the final stage. For this, illustrators mixed pigment in a binding medium. Until the 14th century, the most common medium was glair, which was obtained from egg whites. However, glair was not only difficult to prepare, it also reduced the intensity of the colors. When it was discovered that gum arabic—so readily soluble in water—could be applied more thinly and that the resulting colors were more transparent and intense, gum replaced glair.

|

| Acacia senegal is one of more than 1100 varieties of acacia tree. Most common in the African grassland savannas along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, it is found as far east as Oman and India. During their first two years, seedlings require protection from weeds and livestock, but need little care after that. Drought-resistant, trees can survive sandstorms and temperatures up to 45 degrees Centigrade (113°F), but cannot tolerate frost. When mature, they reach two to six meters’ height (6–20'). Their lateral root system makes them soil stabilizers, useful for erosion control, and researchers give their mineral-rich leaf litter high marks for rehabilitating degraded soils. In several countries, Acacia senegal is part of large-scale sustainable-agriculture, forest-management and rural economic-development strategies. |

In Turkey, illuminators used gum arabic in the application of gold to manuscripts by mixing 24-carat gold leaf with melted gum arabic to make a gold paste. This they applied with fine brushes dipped in a gelatin solution. The ability to judge the correct density of the gold paste and the gelatin prior to application was one of the marks of an accomplished illuminator. Too much gelatin would make the gold look dull, while too little could cause the gold film to crack.

Gum arabic was also important to Turkish scribes for making lampblack ink, which was obtained by burning linseed oil, beeswax, naphtha or kerosene in a restricted airflow. The resulting imperfect combustion produced a fine black soot that could be collected on the inside of a cone or tent of paper or a sheepskin placed above the flame. The soot—lampblack—was then mixed with gum arabic and water. The carbon particles in the ink did not dissolve but remained suspended in the water, thanks to the emulsifying qualities of the gum. When the ink was applied to the paper, the particles remained on the surface, offering a smooth appearance. In case of an error, they could be easily wiped or scraped away. In contrast, most modern inks are solutions that are absorbed into the fibers of the paper.

|

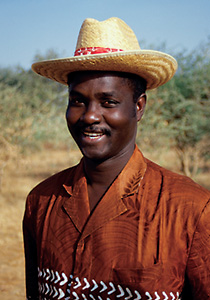

| In Niger, Boureima Wankoye, with his brother Boubacar, are leaders in developing private-sector production of gum arabic. Using seedlings imported from Sudan, their operation provides work for some 6000 rural families. In 2003 the United Nations Environment Program named Wankoye to its Global 500 Roll of Honor, one of eight individuals selected worldwide as outstanding contributors to sustainable development. |

In Africa today, individual farmers use gum arabic for other, more traditional uses, and heaps of gum arabic can be found in most local markets. It is said to soothe sore throats, assuage stomach and intestinal disorders, treat eye problems and combat hemorrhages and the common cold. It can be used as an emollient, astringent or cosmetic. The seed pods of Acacia senegal, 8 to 13 centimeters long (3–5") with flat seeds inside, make excellent fodder for livestock. Left unprotected, the trees will be browsed by sheep, goats, camels, impala and giraffe. Dried and preserved seeds are eaten by some people as a vegetable. When the trees have passed their gum-bearing age, the wood is used both for fuel and in charcoal production. The dark heartwood is so hard that it makes excellent weavers’ shuttles. Ropes can be made from root bark fibers.

The modern industrial era has produced an explosion of manufacturing uses for gum arabic. In the 19th century, it was important to early photography as an ingredient in gum bichromate prints. Today it is used in lithography, where its ability to emulsify highly uniform, thin liquid films makes it desirable as an antioxidant coating for photosensitive plates. The same quality also makes it useful in sprayed glazes and high-tech ceramics and as a flocculating agent in refining certain ores. It is a binder for color pigments in crayons, a coating for papers and a key ingredient in the micro-encapsulating process that produces carbonless copy paper, scratch-and-sniff perfume advertisements, laundry detergents, baking mixes and aspirins. It is used in textile sizing and finishing, metal corrosion inhibition and glues and pesticides. Moisture-sensitive postage-stamp adhesives rely on it.

|

| Gum arabic is unique among the natural gums because of its extreme solubility in water and its lack of taste. As a food additive, it has been extensively tested and appears to be one of the safest for human consumption. In beverages, gum arabic helps citrus and other oil-based flavors remain evenly suspended in water. In confectionery, glazes and artificial whipped creams, gum arabic keeps flavor oils and fats uniformly distributed, retards crystallization of sugar, thickens chewing gums and jellies, and gives soft candies a desirable mouth feel. In cough drops and lozenges, gum arabic soothes irritated mucous membranes. Many dry-packaged products, such as instant drinks, dessert mixes and soup bases, use it to enhance the shelf life of flavors. In cosmetics, too, it smoothes creams, fixatives and lotions. |

Gum arabic is also used in sweeteners and as an additive in foods and beverages, as a thickener in liquids, including soft drinks, and in food flavorings. It is used to manufacture pharmaceutical capsules and to coat pills, and in the manufacture of vitamins, lotions and mascara and other cosmetics. Gum arabic is also a valuable addition to sweets, one supplier’s Web site adds, “including chocolates, jujubes, and cookies.”

|

|

|

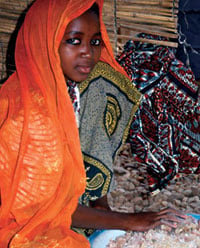

| In the Wankoye enterprise, the women who work in the warehouse are the primary points of quality control, as they are in most other gum-arabic sorting facilities in Africa. Sieving and picking through the bags of gum, they remove sand, dirt, bark, twigs and other undesirable debris, as well as pieces of other, less desirable, gums that individual collectors may mix in with the gum arabic. The gum does not deteriorate if kept dry and can therefore be transported long distances. |

“New industrial uses are likely to ensure growing demand,” says Drew Davis of the US National Soft Drink Association. “The soft drink industry is growing all the time. Production of chocolate and other candy is growing. A growing global middle class, increasingly educated, is driving the demand for printed media. Better health care increases the consumption of pharmaceuticals. Scarcely any industry now using gum arabic is in decline,” he observed.

World trade in gum arabic reached about $90 million in 2000. Some 56 percent of the traded volume came from Sudan, and much of the remainder was exported from Chad and Nigeria. Sudan’s historically dominant position in the modern gum-arabic trade is a result of excellent soil conditions for Acacia senegal in much of the country and the long experience of many Sudanese in collecting and sorting the gum to yield the consistent quality grades that high-tech manufacturers rely on. One major us importer told me that “the tree can grow in Australia, New Mexico, Benin—but the gum isn’t right.”

Mussa Mohamed Karama, former general manager of the Gum Arabic Company of Sudan, points out that several million Sudanese—the country’s population is 29 million—are involved in some aspect of the gum-arabic trade. “The tree doesn’t need foreign components to produce,” says Karama. “You don’t have to fertilize it; you don’t have to water it or add chemicals. It grows naturally, and with minimum effort you collect the gum.” Anthony Nwachukwu, president of Atlantic Gums Corporation, a Connecticut importer of gum arabic, adds, “The employment opportunities at collection centers are really important for women. The gum harvesting season presents them with one of the few opportunities to earn real cash.”

Thus a drop of sap hardened in the hot African sun is plucked, sorted, bagged, shipped, ground into powder and added to a product you purchase, improving its qualities. Also “improved” are the farmer who owns the trees, the laborer who collected the gum and the women who sorted it—a chain of beneficiaries that has existed for at least two millennia, ever since Arab traders first introduced gum arabic to the western world.

|

After 35 years in the United States Foreign Service, Charles O. Cecil retired to devote himself to photography and writing. He first became interested in gum arabic while serving as ambassador to Niger, where local businessmen are working to increase gum-arabic exports. Cecil can be reached at cecilimages@comcast.net. |