|

|

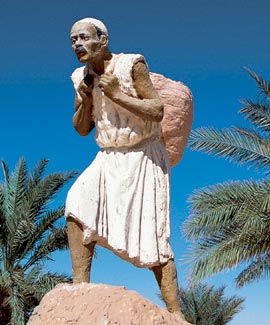

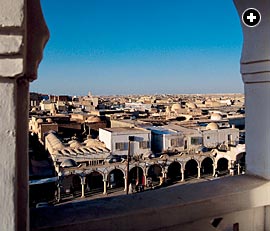

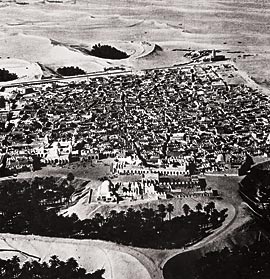

| Above: The statue of the rammaal, the sand porter, at the entrance to Daouia Farm symbolizes the hard labor that was required to grow crops in this desert beginning in the late 14th century. Below: Oasis capital of one of Algeria's 48 provinces, El-Oued, population 110,000, was called "the city of a thousand domes" by early 20th-century traveler Isabelle Eberhart. |

|

Written by Barbara Nimri Aziz

Photographed by Pascal Meunier

t the entrance of a private experimental farm near the city of El-Oued stands a modest statue of an early settler of this oasis: the rammaal. He is neither a camel trader nor a herdsman, although El-Oued has been home to both. Rimal means “sand” in Arabic, and the rammaal is the humble farmer and sand porter whose muscle and plodding determination made El-Oued’s early date palms grow. Far removed from today’s mechanized farming, this figure, weighed down by the sack of sand on his back, is an evocative regional symbol. Far to the north of El-Oued, Algeria’s hills and plains overlook the Mediterranean, from Tlemcen on the western border with Morocco to Annaba bordering Tunisia in the east. Covered by rich loam and fed by seasonal rains, they are Algeria’s most productive agricultural regions, but they comprise only a sliver of a country more than three times the size of Texas. After Sudan, Algeria is the second-largest country in Africa.

t the entrance of a private experimental farm near the city of El-Oued stands a modest statue of an early settler of this oasis: the rammaal. He is neither a camel trader nor a herdsman, although El-Oued has been home to both. Rimal means “sand” in Arabic, and the rammaal is the humble farmer and sand porter whose muscle and plodding determination made El-Oued’s early date palms grow. Far removed from today’s mechanized farming, this figure, weighed down by the sack of sand on his back, is an evocative regional symbol. Far to the north of El-Oued, Algeria’s hills and plains overlook the Mediterranean, from Tlemcen on the western border with Morocco to Annaba bordering Tunisia in the east. Covered by rich loam and fed by seasonal rains, they are Algeria’s most productive agricultural regions, but they comprise only a sliver of a country more than three times the size of Texas. After Sudan, Algeria is the second-largest country in Africa.

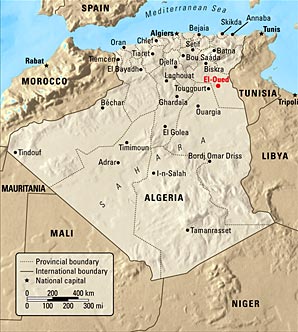

Almost 90 percent of Algeria’s area lies south of the Atlas Mountains, where the land ranges from arid stony plains to shifting seas of desert sand. In many of these arid regions, however, the potential for agricultural productivity exists: They overlie one of world’s largest underground water sources, the Continental Intercalaire. This 600,000-square-kilometer (231,600 sq mi) confined aquifer spreads beneath much of Algeria, Tunisia and Libya; it is second in size only to the Ogallala aquifer of the central United States.

For decades, the full agricultural potential of Algeria’s inland expanses has been overlooked in favor of hydrocarbon exploration, and gas and oil today account for some 60 percent of the Algerian government’s revenues and one-third of Algeria’s gross domestic product. Much of central and southern Algeria, populated by barely three million of the country’s estimated 32 million people, has remained hardly more than a scattering of oases.

But that is changing. Rural development is receiving increasing official support as the Algerian government recognizes that arid-region production not only helps move Algeria toward food independence, but also helps check the expansion of the desert and stanch the flow of young people from rural to urban areas of the country. Regional developers now commonly refer to the value of agricultural programs in El-Oued and other arid regions.

El-Oued is an obvious place for the expansion of agriculture. “There is abundant water. The climate is excellent, and we have a capable, ready population,” asserts Hocine Benyahia, a hydrologist with El-Oued province’s Department of Agriculture. Benyahia passes over the fertility of the sandy soil, citing its proven agricultural value in similar conditions elsewhere in the world. “Forget about the sand. The issue here is how to manage the water.”

|

|

|

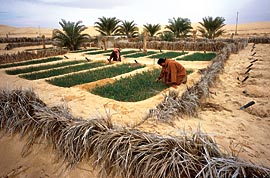

| Top left: Newly planted date palms receive just enough water through drip irrigation. Bottom left: This abandoned village lies within one of El-Oued’s dozens of aghwaat, crater-like depressions first dug by the sand porters to allow tree roots to tap a now-depleted upper water table. Today, this is one of the few aghwaat whose trees survive. Below: Today, new fields are cleared the modern way—by machine—and water is pumped from as deep as 500 meters (1600') below ground, from the world’s second-largest confined aquifer. |

|

|

|

The majority of the 627,000 people (2004) in the province of El-Oued, although ethnically Arab, call themselves Soufi (plural: Souafa). It is a name whose origins reflect the pro- vince’s age-old struggle with sand and water.

El-Oued historian Ali Ghenabzia, who works with folkloric sources in the absence of any written history of early El-Oued, explains that soufi does not derive from the mystical religious sects commonly associated with Islam, but rather from the land itself. It may, he says, come from e-sif, a Berber term for river, which led to the Arabic term wadi al-esouf or oued el-souf, meaning “the valley of the river.” Geologists say a watercourse once flowed through the region, and the town’s name in classical Arabic is al-Wadi (“the valley”), referring to that watercourse, Wadi Sawf. On the other hand, Ghenabzia says, “the desert dwellers of today trace their name to safi, a sand of powdery consistency, or from souf, a blade, referring to the sharp-edged crest of a sand dune.”

For centuries, more than other regions of the country, the Soufi of El-Oued remained true to their Arab origin. Arabic has always been the common language of the Soufi, even during decades when French was the enforced language across most of Algeria. In the late 19th century, El-Oued’s Association of Muslim Scholars founded six schools that taught students from around the country, in Arabic, throughout the remainder of the French occupation. After independence in 1962, when the country urgently needed Arabic-language teachers, as many as 400 graduates from those El-Oued schools were sent throughout the country to reintroduce the national language.

Of themselves, Souafa say they are a people who embrace their environmental extremes and social isolation to advantage. In fact, they credit those conditions with enriching their culture.

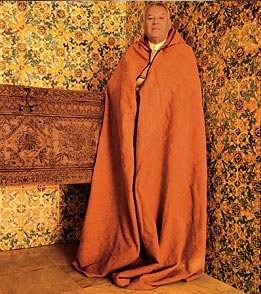

Of the desert, Azzedine Zoubedi quotes a local proverb: fi il’lala, harah’eer, fi il’na’har t’alal—“at night, a thick blanket, in daytime, a tender shade.” In Soufi homes, courtyards are designed with a shallow pit, called a hawsh, in the center—the local equivalent of the central fountain common to the courtyard houses of other Arab lands. Here, guests are received and the family gathers in the evening. On hot nights, some sleep in the cool hawsh. In between houses, even in the era of the automobile, lanes are often rivers of loose, powdery sand. A favorite family picnic spot is likely to be one of the high, sharp-crested dunes beyond the village or town. As so often happens, the same elements that make hardships for people have also their softer, domestic side.

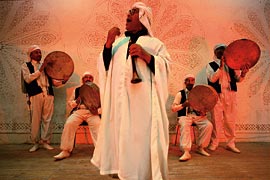

El-Oued’s most renowned singer-poet, Abdellah Menaï, is nationally recognized by young and old with affection. As one admirer in the capital put it, “his words are pure Arabic.” Comments another: “He speaks with the people’s voice.” Menaï, who lived in France and worked in Algiers during the 1970’s, says of his own work, “I could not accept the ‘Algiers style’ with its mix of languages. I left my friends in the capital to return to the desert and listen to our local poets, especially Soufi women. They have given me much. All of us are imbued with the lullabies our mothers sang to us. I keep those words and rhythms in my music.”

Today, in towns across El-Oued province, Soufi poets gather regularly to share their work. Their poetry may not be widely acknowledged in Algeria’s highbrow centers, where classical Arabic and French prevail, but in a time when urban cultures are ever more dominant, Soufi poetry is holding its own.

“Theirs are the lines that move people,” notes anthropologist Ahmed Zegheb. Also a linguist and lecturer in Arabic literature at El-Oued University, Zegheb sends his students into the community to collect poetry and other materials from folk sources. “We can also discover the anthropology of our ancestors through Soufi poems proverbs, riddles and jokes.”

|

The first accessible level of water, closest to the surface, he explains, was a shallow supply, and it was exhausted in this region by 1960. The next-deepest level, at 200 to 500 meters (640–1600') is too salty for agriculture. The third, below 500 meters, “is pure, and because it is hot, it rises to the surface from its own pressure. It is our main water source nowadays.”

On an average workday, Benyahia is often out in the fields, working with other experts to build water-drainage networks, including planting eucalyptus trees that naturally drain salty, water-logged soil, laying grids of pipe and installing pumps, and selecting irrigation techniques suited to local conditions. With his contagious energy and enthusiasm in the face of challenge, he may well be the rammaal’s modern, well-educated descendant.

|

| Above: Daouia Farm, founded in 1985 by Djilali Mehri. Below: Produce from the exerpimental farm. |

|

t the end of the 14th century, an Arab immigrant called Sidi Mastour came to El-Oued from the eastern Sahara, bringing with him what would become El-Oued’s first commercial date-palm seedlings. His belief that they could flourish in El-Oued proved correct, and he eventually made eastern Algeria the leading producer of dates in North Africa.

t the end of the 14th century, an Arab immigrant called Sidi Mastour came to El-Oued from the eastern Sahara, bringing with him what would become El-Oued’s first commercial date-palm seedlings. His belief that they could flourish in El-Oued proved correct, and he eventually made eastern Algeria the leading producer of dates in North Africa.

To reach the water table, then some 15 meters (48') below the surface, Mastour and his companions excavated crater-like, sunken farms, called aghwaat (singular is ghawt), into which the date palms were planted. Each ghawt required carrying up and away countless tons of sand—first to dig the ghawt, and then to continually haul away sand that blew into it. A single ghawt held 50 to 300 trees, and a large one could sustain three or four families. So it was that thousands of families thrived in El-Oued on the strong backs of the rammaals, despite inhospitable winds, heat and isolation, and the oasis grew into the capital of a province to which it gave its name.

Today, the remnants of hundreds of aghwaat speckle the landscape. Tufts of green palm fronds protrude from some, but none are productive any longer. Unbeknownst to the farmers, the sand in which they planted contained salts that the irrigation water mobilized, and by the second half of the 20th century their palms had perished. The ghawt system had to be abandoned.

|

| Djilali Mehri |

Just as Sidi Mastour and his tribe, 500 years ago, managed the sand by hauling it away, controlling the sand here remains essential if today’s new agricultural initiatives are to succeed. From behind the dunes emanates the ever-present grinding of bulldozers as they shift rolling sands into flat, arable plots, bordered by palm-frond fences and rows of hardy shrubs. These leveled fields can be fed by water drawn from the aquifer far below.

These techniques are opening up new possibilities as date-palm cultivation, still expanding, is augmented by new crops of potatoes, pears, pomegranates, peanuts and—most recently —olives. Agriculturalist Adel Guedouda explains that, in general, trees stimulate humidity, and, specifically, olive trees are a good natural water pump.

Daouia Farm, founded by Djilali Mehri, a native son of El-Oued who was successful in international commerce before turning to agriculture, sets the pace for local innovation. Neither a farmer nor the son of a farmer, Mehri simply believed that his homeland could produce anything, and he foresaw the possibilities offered by the then-new technologies of hybrid seedlings and drip irrigation. Beginning in 1985 with 54 hectares (133 acres), and now farming a dense expanse of 700 hectares (1730 ac), Daouia produces pears, pomegranates and pistachios, all marketed nationwide and gradually entering the European market. He planted date palms, eucalyptus for its value in water management, and, in 1990, he introduced olive-growing to El-Oued, his most promising innovation.

|

|

|

| Top: Women sort dates at Daouia Farm. Above left: Manager Azzedine Zoubeidi takes particular pride in the farm's olives. Above right: Limem Menana is Daouia's foreman. |

To reach the olive groves, visitors pass first through the vaulted hall, its qubbah, or cupola, decorated with intricate carved-gypsum designs, where the farm hosts seminars at which international experts, local farmers and students gather to discuss new concepts and methods. Through lanes lined with flowers, they enter the orchard of 5940 olive trees. Daouia’s manager, Azzedine Zoubeidi, notes that each tree produces an average of 80 kilos (200 lb) of fruit annually, “far more than established farms elsewhere, including in Italy, Spain and northern Algeria.” The press at the farm extracts the oil “within hours” of the harvest, and this timing, he maintains, yields oil whose 0.5 percent acidity is lower than the 0.8 percent international standard for “extra virgin” olive oil.

|

| Above: Greenhouse tomatoes. Below: Garlic. |

|

While Daouia Farm appears to be a dramatic testimony to what can be accomplished on this land, some officials say its value as an example is limited. They point out the extraordinary investment the farm has required, indicating that it is more experimental than profitable. But this view is complicated by the checkered history of agriculture in the country.

In 1962, after Algeria’s liberation from 132 years of French rule, the new government turned its attention more toward the cities and coastal regions than the interior. By the 1980’s, the widespread failure of inappropriate agricultural models had led to a decline in farming, and the country became increasingly dependent on food imports. Even today, despite advances, Algeria is one of the largest per-capita food importers in Africa.

Then, in 1991, strife broke out in what Algerians now call the “red decade,” a reference to a near–civil war that left the entire country, and particularly its rural areas, isolated and unable to advance. Basic infrastructure fell into disrepair. Industrial production collapsed, except for scaled-down oil and gas production, which also suffered from the low world prices of that decade. As a result, produce could not reach markets, and Algeria’s import-dependence rose further. Villages in the interior were depopulated as people fled for safety to the crowded coastal cities and to Europe. Desertification was left unchecked.

In 2000, newly elected President Abdul Aziz Bouteflika launched serious, peaceful efforts to put an end to the rebellion, and even before security was completely reestablished, Algiers launched an ambitious five-year development plan that allocated billions from gas and oil revenues to reconstruction. The agricultural sector received $2 billion, and in a second five-year plan, begun in 2005, it is slated to receive $4 billion. From 2005 to 2010, the southern and central provinces will receive a significant portion of the allocation.

|

| Above: Potatoes, carrots, and new date palms—cultivation of these and other crops is rebounding throughout the region after Algeria's decade of conflict. In addition to jobs, former El-Oued governor Omar Hattab says candidly, a goal of government support for agriculture is "to restore credibility and respect for the Algerian government." |

|

Mohammed Lahouati is director of the ministry’s development program in arid zones. “In Biskara to the north [of El-Oued], we have to drill down 800 meters (2600') to reach water, drawing on the same aquifer as El-Oued,” he says. El-Oued, “for all its sand, has abundant easily accessible water. Considering the extreme conditions of El-Oued’s environment, extra effort is needed from the farmers themselves. We are very satisfied with progress there.”

That extra effort in El-Oued seems to have come not just from modern-day rammaals in the field, but also from public servants. Widely credited for the region’s recent strides is Omar Hattab, who governed the province from 2002 until last year.

“Our development is now founded on reality,” Hattab says. At the same time, he is convinced “we can grow anything here.”

He oversaw the development of 10,000 new arable hectares (24,700 acres) and the creation of a green belt that now rings the provincial capital. Unemployment, he adds, has begun to drop, reversing a sharp post-1991 increase, “and the province is now exporting potatoes to the northern cities.”

|

| Above: El-Oued architect Bendiaff Messaoud blends traditional and modern in many of the city's newest buildings, including the one below at the city's university. |

|

Hattab also supported a national homesteading initiative designed to pull young, educated people, frustrated by the lack of the white-collar jobs they trained for, into farming. “They receive special support to take up farming,” he explains. “If they succeed within five years, they assume 100 percent ownership of their homestead.” Young men, trained in agricultural technology, work with experts brought from outside the province.

Hattab’s other innovations include anti-desertification installations, as well as support for the adaptation of traditional architecture to modernize the market center and embellish new government buildings with traditional Soufi designs. The city’s new administrative center, airport, university residences and museum, and the sports center now under construction, all incorporate those art forms. El-Oued architect Bendiaff Messaoud, who specializes in traditional materials and designs, says, “My projects incorporate our qubbah, the distinctive cupola, a vaulted roof with the ceiling decorated by local carvings just like the ones our ancestors had in their humble homes.” Early 20th-century adventurer Isabelle Eberhart described El-Oued as “a city of a thousand domes,” and today she would see double that number.

Most ambitiously of all, Hattab put government support behind an olive-cultivation project not unlike that at Douia Farm, but more ambitious: Launched in 2003, it calls for one million olive trees to be planted by 2010; today, the first 35,000 are in the ground.

|

| Above: An aerial view of El-Oued from the early 1950's shows three aghwaat in the foreground, and others behind the town. Below: El-Oued singer Abdella Menaï serves up "pure Arabic" to his audiences. |

|

The speed of agricultural development, and the largely free hand Algiers has given energetic officials such as Hattab, sends a message that the government is using its oil and gas revenues for the nation. As a result, the country is recording its first real growth since 1991, estimated for 2005 at a very high seven percent. Although the country is still dependent on food imports, Algeria’s balance of trade for the first eight months of 2005 ran a surplus of $13.8 million.

Late last year, President Bouteflika launched a $60-billion, five-year program he sold as “Algeria’s own Marshall Plan, to maintain strong economic growth, create jobs and rebuild damaged infrastructure.” Around the same time, he also announced that the nation’s foreign debt, largely incurred during the 1990’s, would fall from $21 billion to $10 billion by 2010.

Viewed from the sands of El-Oued oasis, the country’s plans and projects constitute a very ambitious task, but not one particularly daunting to a people accustomed to harsh winds and the rammaal’s sand-laden, uphill labors. Nadhir Haddana, director of a youth center in El-Oued, says that, in his opinion, “people have begun to feel change is really here, with new opportunities for anyone willing to work. El-Oued, which we feel was neglected for decades, is getting proper attention.”

|

Anthropologist and journalist Barbara Nimri Aziz has made several visits to Algeria in recent years. Former director of the Radius of Arab American Writers (RAWI), she produces the weekly program “Tahrir” (www.radiotahrir.org) on Pacifica-WBAI Radio from New York. |

|

Photographer Pascal Meunier (pascalmeunierphoto@yahoo.com) lives in Paris. He specializes in photographs of Africa and the Islamic world, and is represented by the Cosmos and Arabian Eye photo agencies.

|

This article appeared on pages 24-33 of the March/April 2006 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

See Also: AGRICULTURE, ALGERIA, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, EL-OUED, WATER

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for March/April 2006 images.