aste has a strong effect on our sense of well-being and our social identity. Food informs us who we are, how well we are, and even how far we are from home. Few things are more intimately linked, more closely implicated, and more sweetly (or bitterly) sensed in our life’s journey than food. Just how closely food resonates with other changes in a society is, therefore, an intriguing issue.

aste has a strong effect on our sense of well-being and our social identity. Food informs us who we are, how well we are, and even how far we are from home. Few things are more intimately linked, more closely implicated, and more sweetly (or bitterly) sensed in our life’s journey than food. Just how closely food resonates with other changes in a society is, therefore, an intriguing issue.

In northern Pakistan, in the high valley of Hunza, food practices have changed profoundly during the last 50 to 60 years. For decades, access to Hunza, in the heart of the Karakoram mountains (Western Himalayas), was quite difficult. But following its secession in 1947 from the maharajah’s government of Jammu and Kashmir, Hunza shifted from an indentured agricultural economy, anchored by local hereditary rule (mirdom), to a state-driven national and global market economy. A benchmark of these changes was the completion in 1978 of the international Karakoram Highway. Traversing the valley, the highway became a thoroughfare between Islamabad and Beijing, and it opened Hunza to a variety of extraordinary changes. The changes in food and foodways reflect much of what happened and bring to view a new awareness of what “traditional” means.

It is actually something of an irony to document this cooking as “traditional” because most Hunza households are still making the dishes reproduced here. The difference is that older people knew a time before the construction of the Karakoram Highway when rice, chutneys, curries, processed sweets and other delectables were rare. Now they are commonplace in local bazaars, and younger people accept the various national and global products as ordinary. Yet with the opening of Hunza to outside influences, local women saw Pakistani foods privileged over their local dishes. They saw the time-honored fare that they offered as young brides relegated to sideshow events at community celebrations. They recognized that, as the new and tasty foods from beyond the valley became popular, part of their own identities was being diminished and marginalized  as “traditional.” Disappearing from view was the earlier context to which both the food and the women who cooked it belonged. If you were to read these recipes from the perspective of an elder Hunzakutz, you would know the time of year any dish was eaten, as well as its place in a disciplined sequence of annually consumed foods. You would also know folktales to go with different dishes, steeped in tradition, told and retold.

as “traditional.” Disappearing from view was the earlier context to which both the food and the women who cooked it belonged. If you were to read these recipes from the perspective of an elder Hunzakutz, you would know the time of year any dish was eaten, as well as its place in a disciplined sequence of annually consumed foods. You would also know folktales to go with different dishes, steeped in tradition, told and retold.

Overlooked by the shining slopes of Rakaposhi, which rise nearly 6000 meters (19,200') from the valley floor, the apricot orchards and wheat fields of the Hunza Valley wind along the Hunza River. Top: Over less than a generation, Hunza foodways have adopted many imports that come via the Karakoram Highway that runs through the valley, connecting Islamabad to the south with China to the north.

MAP: MARIELLE PALEY |

|

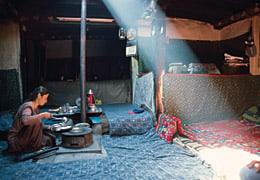

The disappearing context that cradled such stories also included the punishing labor of women’s lives. They tended fields scattered up the mountainside, while at the same time raising babies and feeding their families. They carried loads on their backs that weakened their knees and stiffened their joints. They raced against time and shuddered at the tempests of rain and sandstorms, hoping to protect their perishable harvests. In their “free” time, they searched for salty-tasting earth and hauled it back home to enrich their cooking stock.

While preparing the dishes for this book, the women of Karimabad in the Hunza Valley lamented that their recipes could never taste the same as they had in the past. Salt sold in the bazaar, either granulated or as hunks of rock, had a different flavor than salt from local sources, they said. Flour formerly ground at a local water mill had a different texture than the flour now produced by an electric mill, and this was different again from flour imported from China. For the oldest, the bokhari (steel oven) had itself been an innovation, for they had learned to cook at the shee (hearth), using stone pots, when there was no shuli (stovepipe) to remove smoke from the single-room farmhouse. All of them knew the difference in taste between phitti (wild-yeast bread) buried to bake in hot ashes and phitti baked in an electric oven. All knew a time when there was only one cooked meal in a day—two, if they were lucky—and when a meal was a single dish sometimes eaten out of a common pot. They also knew that their simplicity and their manners sometimes embarrassed young people: Why offer the same glass of water to others when there were glasses enough for everyone, a younger person might ask—and yet elders remember when there was only one glass in the house and it was customary to offer that filled vessel to everyone present before raising it to one’s own parched lips.

|

|

| Left: A woman uses a wood-fueled stove inside her home in the town of Karimabad. Right: Rice does not grow at Hunza’s altitude, but wheat thrives, and it provides the staple grain of Hunza cuisine. |

So it is that the “traditional” underlies life-shaping experiences. The Karimabad women thus added something of their life histories to the recipes we collected through their fierce labors of love, which have made generations of women and their fathers, husbands, brothers, sons and daughters happy and well-nourished. We, in collecting these recipes, and you, in recreating them, honor the cultural heritage of the unspoken heroes and heroines of Hunza.

—Julie Flowerday

|

|

|

|

| Wheat is Hunza’s main staple food. Rice, otherwise so common in Asia, cannot be grown in the mountainous terrain and high-altitude climate, and so different breads and wheat-based dishes replace it. Other grains such as buckwheat and barley are also cultivated. |

Maltash is “aged butter,” prepared from milk that is scalded before churning. Its strong taste is so valued that maltash is a gift for births, weddings and funerals—taxes can even be paid in maltash. The older the maltash, the more valuable it is. Wrapped in birch bark and buried in the ground,it may lie for years or even decades before the head of the family decides it is time to dig it out. |

Kurutz is a salty, sour, rock-hard cheese that is a favorite soup flavoring. It is made by boiling down lassi (see page 43), together with a piece of older kurutz that gets the enzymes started, as in sourdough bread. The resulting soft pasteis pressed and sun-dried. Similar cheese is made from Mongolia to Tibet. |

|

|

|

| Dried apricots are a favorite snack and an ingredient for soups and juices. The valley is known for its abundance of apricots, most of which are collected in late summer to dry in the sun on rooftops, walls and boulders. |

Apricot kernels are very similar to almonds in taste and used in much the same way, as a snack and for cooking. Children often crack the hard shell of the apricot pits with a stone to get to the delicious kernel. |

Apricot oil is traditionally extracted from the kernels by hand, though machines are slowly replacing the hand-work. There’s a sweet and a bitter apricot oil: The sweet is for cooking; the bitter is a beauty product for skin and hair. |

|

|

|

Tumuro is a native wild thyme which is found in the mountains surrounding the valley. It is used fresh

and dried. |

Coriander is not native to Hunza, but it grows easily in the harsh climate, and it is a very popular herb to season soups andmeat dishes. |

Turmeric usually comesas a bright yellow powder and is also a favorite import. It is mainly used in small quantities to color soups and other dishes. |

|

Hunza’s ubiquitous chappati is actually a culinary import from the south. Really traditional Hunza bread is a thin wheat bread known as the khamali. Compared to a chappati, it is much larger in diameter, and the reason was practical: Wood for cooking fires is precious, and by baking a large piece of bread you can take advantage of the heat on the rather large cooking plate of a traditional Hunza stove. Phitti is probably the most famous of all Hunza breads and a common breakfast food. Thick and nutritious, with a crusty outside and a soft interior, it is time-consuming to prepare: The dough is put into a sealed metal container, and after all the other cooking has been done at night, the phitti is tucked into the embers of the hearth, where it bakes overnight. |

|

People call it buttermilk, lassi or simply a yogurt drink. Traditionally, diltar is prepared in a goat- or sheep skin which is shaken or rolled on the ground until butter forms. An alternate method uses a tall, narrow wooden cylinder and a long, thick pole in a process much like churning butter. Nowadays, the simplest way to make diltar is to mix yogurt with an equal amount of water and blend at high speed for a few minutes. Add salt, sugar or fruits like bananas or mangos as you please. |

Social anthropologist Dr. Julie Flowerday has lived and worked extensively in the Hunza Valley. Her e-mail is flowerda@email.unc.edu. |

Marta Luchsinger, who coordinated production of the recipe book, visited Hunza as a doctoral student at the University of Bath. |

|

Mareile Paley is a graphic designer who lives in Hong Kong with her husband, free-lance photographer Matthieu Paley (www.paleyphoto.com). |

|