|

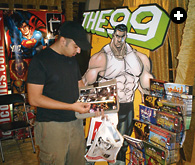

| Released in November, the cover of the first English edition of The 99 featured heroes Jabbar and Dana and their trainer, Zoran. Below: Kuwaiti psychologist Naif Al-Mutawa, author and publisher of

The 99, sketched his business plan for Teshkeel Media Group in the classic style: on the back of a napkin in Times Square. |

|

| ALEC MARBELLA |

Written by Piney Kesting

Photos and Illustrations Courtesy of Teshkeel Media Group

The setting: London, a gray and chilly day. Al-Mutawa and his sister Samar were sharing a cab across town. During their conversation, Samar reminded Naif of his desire to return to his first love—writing. “I was one of those people who had wanted to be a writer ever since I was a little kid. My parents were very supportive, as long as it was only a hobby,” recalls Al-Mutawa. One thought led to another, and by the time he stepped out of the cab, the first seeds of The 99 had been planted.

Later that summer in New York, he sketched out a business plan on the back of a napkin in the Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Times Square. The goal was to create a band of superheroes based on Islamic archetypes, each imbued with one of The 99 qualities that the Qur’an attributes to God.

Al-Mutawa explains that, during his clinical training in the 1990’s at New York’s Bellevue Hospital, he worked with many Arab survivors of torture. Later, in Kuwait after the Gulf War, he treated former prisoners of war and other patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. “Those experiences made me very aware of the lack of heroes, and of the need for them,” he says. It also led to the 1996 publication of his first children’s book, To Bounce or Not to Bounce, which later won a UNESCO award for literature in the service of tolerance.

Thanks to a former business-school classmate, Al-Mutawa landed a meeting with Tom DiFalco, a former editor- in-chief of Marvel Comics, and Neil Adams, a renowned DC Comics illustrator. DiFalco and Adams “told me my concept was a comic-book project,” Al-Mutawa explains. Others found his idea exciting enough to back it with cash: By June 2004, he had raised more than $6.8 million from 54 investors in eight countries, and he established the Teshkeel Media Group (TMG) in Kuwait. Its mission: positive, inspirational comics and media products for children in the Arab and Islamic worlds, with The 99 series as its cornerstone. At that point, Al-Mutawa recalls thinking, “I have the money. I have the idea. Now what?”

“From the first moment Naif called and told me about The 99, I thought it was a terrific idea, both from the social and business points of view,” comments Larry Durocher, former publisher of Rolling Stone magazine and a consultant to the project whom Al-Mutawa regards as a mentor. “It seemed it could be a profound door-opener for people to better understand each other, and to understand what Islam is all about.” Encouraged by Durocher and other professionals, Al-Mutawa assembled a top-notch international management and artistic team, many of whom had worked in New York for Marvel Comics.

Sven Larsen, former director of marketing and creative services at Marvel, joined Teshkeel in 2005. “I was attracted to the challenge of bringing comic books and pop culture to a part of the world that was significantly underrepresented in that regard,” he explains. “There is an unmet demand for popular culture based on Islamic and Arabic history that’s crying out to be filled. It is compelling for kids to have heroes who speak, act and look like them.” Larsen adds that he was also intrigued by the story of The 99. “It was exciting to come across a new story, one that was not based on the cultures or mythologies I was familiar with. Given the problems in the world today, I wanted to be involved in a project looking to bridge the gap between cultures and promote peace and tolerance.”

Sven Larsen, former director of marketing and creative services at Marvel, joined Teshkeel in 2005. “I was attracted to the challenge of bringing comic books and pop culture to a part of the world that was significantly underrepresented in that regard,” he explains. “There is an unmet demand for popular culture based on Islamic and Arabic history that’s crying out to be filled. It is compelling for kids to have heroes who speak, act and look like them.” Larsen adds that he was also intrigued by the story of The 99. “It was exciting to come across a new story, one that was not based on the cultures or mythologies I was familiar with. Given the problems in the world today, I wanted to be involved in a project looking to bridge the gap between cultures and promote peace and tolerance.”

|

|

|

| ALEC MARBELLA |

| From left: Tarek Hosni, editor-in-chief at Teshkeel, consults with Al-Mutawa. Mirna Dakik edits copy. Designers Hasaan Kanaan and Mohamed Azab confer on a layout. |

Fabian Nicieza, an acclaimed writer in the American comic-book industry, best known for top-selling Marvel titles such as X-Men and X-Force, joined Teshkeel’s team as co-writer of The 99.

|

| SVEN LARSEN (2) |

| Illustrator Dan Panosian and writer Fabian Nicieza both worked on numerous Marvel Comics best-sellers. |

|

“I understand how it is when people have not had heroic characters to call their own,” comments Nicieza, who emigrated from Argentina to the United States when he was a child. “I was enthused to work with someone who has a chance to bring his dreams and ideas to life. I respect Naif’s beliefs. We have a real chance to do something here that can affect people positively.”

Working together over more than a year, Nicieza and Al-Mutawa fine-tuned the character guide and story line. The plot is built on a historic event familiar to every schoolchild in the Middle East—Hülegü Khan’s invasion of Baghdad in 1258. It was, as the story begins, “a time of dark and light....”

As the Mongols invade Baghdad, they are intent on destroying the city’s great libraries, foremost among them the renowned Bayt al-Hikmah (“The House of Wisdom”). During the battle, its books are thrown into the Tigris River by the thousands, turning the waters black with ink. But unbeknownst to the Mongols, the librarians, the huras al-hikma (“The Guardians of Wisdom”), have hidden the library’s ancient knowledge in 99 mystical gemstones, called the Noor (“The Light”) Stones, which the huras move to safety in faraway Granada, in Muslim Spain. There, for centuries, the Noor Stones lie concealed inside the dome of the Great Fortress of Knowledge, built by the huras. One fateful day in 1488, as King Ferdinand’s Spanish army approaches, the fortress explodes. The huras disperse across the globe, carrying with them the precious Noor Stones; no one hears of them again.

The tale fast-forwards to the present. Dr. Ramzi Razem, a psychiatrist, has spent his life searching for those gems. He believes they have been recently found, and that each Noor Stone is possessed by a young person somewhere across the globe. He has made it his mission to find these heroes-to-be and teach them how to use their new powers to battle against darkness, both within their own souls and in the outer world.

|

|

|

| ALEC MARBELLA |

| From left: Sven Larsen, chief operations officer, Saad Al-Bitar, production supervisor, and Frankie Shum, vice president of finance, guide the two-year-old business, which attracted an initial 54 investors from eight countries. Vivian Salameh translates the English script to produce the Arabic edition. Days before the launch of The 99, a visitor in Kuwait’s Marina Mall looks over Arabic editions of Marvel comics. |

When asked if Ramzi is Al-Mutawa’s fictional alter ego, Nicieza laughs and admits that “the passion and desire to do something right and good is all true to Naif, but he will never be as tall as Ramzi!”

“Strength, honor, truth, mercy, invention, generosity, wisdom, tolerance—these are some of the superpowers possessed by my heroes,” emphasizes Al-Mutawa. “No one hero has more than a single power, and no power is expressed to the degree that God possesses it,’’ he adds. There are 99 young heroes from 99 countries, from all walks of life. All of them are Muslim, but not all are Arabs, and the number is almost evenly split between boys and girls. As Al-Mutawa explains, whenever these characters collaborate to solve problems, there is an implicit message of tolerance and acceptance, a theme central to the series.

Unlike many comic book heroes, the 99 do not use weapons. “They use the gifts they have within themselves,” Al- Mutawa notes, adding that “The 99 is not about what kids shouldn’t be doing. It’s about learning how to use the power within them to make a difference.”

Nicieza agrees. “I want the readers to understand that when you are young, you don’t always do the right thing. You will make mistakes and you will learn from them.” He adds that because these characters are just discovering their powers, they are less than perfect, and that allows readers to identify with them. But, in the long run, the characters band together to do something constructive. ‘‘That’s a very important and positive message to send out these days,” Nicieza emphasizes.

Nicieza agrees. “I want the readers to understand that when you are young, you don’t always do the right thing. You will make mistakes and you will learn from them.” He adds that because these characters are just discovering their powers, they are less than perfect, and that allows readers to identify with them. But, in the long run, the characters band together to do something constructive. ‘‘That’s a very important and positive message to send out these days,” Nicieza emphasizes.

The original character designs were drawn by artist Dan Panosian, who is well-known for his work on X-Men, Spider-Man and The Hulk. Bringing his ideas to print is an international team: John McCrea in Birmingham, England pencils in Al-Mutawa’s and Nicieza’s preliminary script (“A cracking good read!” he calls it), and then the book is sent to inker Sean Parsons in Ohio. Once the artwork and final script have been approved, it goes on to colorist Monica Kubina, and then to Comicraft, a lettering team in Los Angeles. While the visuals are being finalized, the editorial team in Kuwait translates the English text into Arabic.

Last summer, prior to the publication of the first issues of The 99, Al-Mutawa, accompanied by two of his four young sons, took a long-overdue vacation and returned to the New Hampshire summer camp where he had read his first comic book in 1979. In a public letter he wrote afterward, he explains that “The 99 is all about making a conscious choice not to let others define who you are. It is about being proactive in choosing the backdrop against which you are to be judged. Islamic culture and Islamic heritage have a lot to be proud and joyful about. The 99 is about bringing those positive elements into global awareness. I spent the better part of last year telling the world that next Ramadan, the world would have new heroes. Now it does.”

|

| A young fan finds coloring material at Teshkeel’s promotional booth in Kuwait City. “The 99 is all about making a conscious choice not to let others define who you are,” says Al-Mutawa. |

Three years after Al-Mutawa stepped out of that cab in London, Teshkeel Media Group has become one of the leading developers of comics and children’s entertainment in the region, as well as the exclusive Arabic translation partner for Marvel, Archie and DC Comics. Earlier this year, Teshkeel introduced the legend and characters in an “Original Special,” which whetted readers’ appetites for the further adventures of Dr. Ramzi and his superheroes. Then, when the first monthly English and Arabic issues of The 99 hit bookstore stands on November 5, sales exceeded Al-Mutawa’s expectations.

Like his fictional characters, Al-Mutawa seems to have discovered his own Noor Stone—one which enables him to offer children in the Arab and Islamic world a new beacon of light. And for many children inspired by The 99, that makes him a real hero.

Teshkeel Media Group shares the Middle Eastern comic-book market with Cairo-based AK Comics. Founded in 2003 by American University of Cairo economics professor Ayman Kandeel, AK Comics follow the adventures of four futuristic superheroes—Aya, Zein, Jalila and Rakan—as they strive to bring peace to the Middle East.

Drawn in studios in the US and Brazil and published in Egypt, the first 300 copies of Zein: The Last Pharaoh appeared in 2004. Today, the monthly series, published in both Arabic and English, has a distribution of approximately 50,000. To ensure that the comic is available to everyone, it is printed both in color and in a less expensive black-and-white edition, and several thousand free copies are donated to orphanages and underprivileged children throughout Egypt. Like its fictional heroes, AK too has a positive mission to encourage reading and to provide inspiring role models for children in the Middle East.

“The history of comic books in the Middle East is really a case of a culture interrupted,” explains Sven Larsen, chief operating officer of the Teshkeel Media Group, noting that Egypt had a long history of creating and reading comic books. Prior to the Lebanese civil war, Lebanon was also a major publisher of translated Western comics. In the late 1960’s, Illustrated Publications in Beirut produced Arabic translations of Superman, Batman and Robin, The Lone Ranger, Tarzan, The Flash and numerous other well-known western comics. Over 2.5 million copies of these comics were distributed in 17 countries through the early 1970’s.

According to Larsen, the success of both Teshkeel Media Group and AK Comics illustrates that media produced in and for the Arab and Islamic worlds are as valid as any coming from traditional markets in America, Japan and Europe. “It also sends a good message,” he notes: “That there are no limits on what young people in Islamic and Arab societies can accomplish.” |

www.teshkeel.com

|

Piney Kesting is a Boston-based free-lance writer who found her own Noor Stone the first time she traveled to Lebanon. She has been writing about the Middle East ever since. |