|

| Top row: fresh goat’s-milk yogurt cheese, labne, kashk. Bottom row: cow’s-milk yogurt, çökelek, kaymak. |

Written and photographed by Eric Hansen

ne bitterly cold morning in mid-November of 1972, I left the open-air bus terminal of Erzurum, in eastern Turkey, in search of warmth. In a nearby small restaurant, huge cauldrons of thick, steaming soup were bubbling away over smoky wood fires.

ne bitterly cold morning in mid-November of 1972, I left the open-air bus terminal of Erzurum, in eastern Turkey, in search of warmth. In a nearby small restaurant, huge cauldrons of thick, steaming soup were bubbling away over smoky wood fires.

Breakfast was being served at rough wooden tables filled with neighborhood workers. As I soon discovered, the soup was an eastern Anatolian specialty called yoğurt çorbası (pronounced yo-oort chor-ba-sih). Çorba, derived from the Persian word shurba, is the Turkish word for soup.

|

|

|

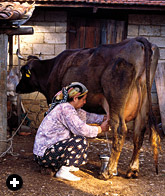

| Sulfer Kazık milking the family cow in preparation for making yogurt, straining the fresh milk and heating it in a tinned copper pot. |

I had never before considered yogurt as a possible ingredient for hot soup: For me, yogurt had always been something to eat fresh on cereal, or blended with cracked ice into a cold drink with fresh fruit and honey. But at the first taste of that flavorful, warming soup, fragrant with the aromas of chicken stock and cilantro, I realized that yogurt was far more versatile than I had ever imagined. To this day, yoğurt çorbası remains one of my staple dishes for the cold winter months.

Over the years I learned how to make yogurt and how to prepare it in a wide variety of different ways, but I knew virtually nothing about where yogurt originally came from, how it’s made, or what distinguishes traditional “live” yogurt from the mass-produced, store-bought products of the same name.

Consulting various Eastern Mediterranean cookbooks, especially Classical Turkish Cooking by Ayla Algar, A Book of Middle Eastern Food by Claudia Roden and Alan Davidson’s encyclopedic Oxford Companion to Food, I began to unravel and explore the history and myths associated with traditional yogurt.

Live yogurt is a fermented dairy product made by mixing a starter culture with warm milk and then letting it sit, undisturbed, in a warm place until it becomes firm. The smooth, soft curd of live yogurt, with its partially separated whey, has a slightly acid, nutty flavor and a creamy texture unlike any other fermented dairy food.

But how does it happen? At milk temperatures between 32 and 43 degrees Celsius (90–110° F), the ideal one-to-one ratio of bacterial strains of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus breaks down part of the milk sugars to produce one to 1½ percent of lactic acid. Coagulation takes place when the milk proteins configure themselves into a lattice to which minerals, sugars and fats, naturally found in milk, attach themselves. The lactic acid and other by-products of the fermentation—including carbon dioxide, acetic acid, acetaldehyde and dacetyl—all contribute to the characteristic flavor, texture and taste of yogurt.

In contrast, today’s supermarket shelves are filled with an astonishing variety of mass-produced yogurt products that often have little in common with live, full-fat yogurt. They are, generally speaking, low- or non-fat, artificially colored and flavored, overly sweetened, pasteurized (so the beneficial bacteria are killed), pre-mixed with fruit, and combined with pectin, gums and even cellulose fiber to provide a desirable texture. The excellent texture of traditional live whole-milk yogurt is due to its high percentage of milk solids, rather than artificial stabilizers. The majority of commercial yogurts do not have the texture or the culinary versatility of true yogurt.

|

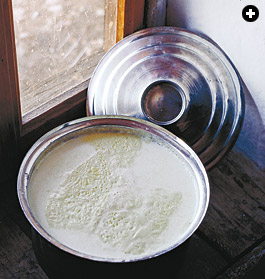

| Warm cow’s milk “inoculated” with the starter culture—the beginning of the yogurt-making process. |

The first yogurt was most likely created by chance. The two benign bacterial strains (L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus) are often found in milk and also in the gourds or animal-skin bags used thousands of years ago to carry liquids. When they happened to come into contact with milk, they caused it to ferment and solidify into a clabbered mass that humans realized was tasty and lasted longer than fresh milk. When this first happened, though, is subject to extensive and ongoing debate. Curdled milk, as a food, is mentioned in the Bible (Job 10:10). The Canadian Dairy Association has recently suggested a date as early as 10,000 BC for the dis-covery of yogurt, based on the approximate date that cattle were first domesticated in what is now Libya. Curdled or soured milk would have been known at that time, but was it yogurt?

|

|

|

| From top: A pot of fresh cow’s-milk yogurt with its characteristic wrinkled top layer of kaymak; Sulfer Kazık pouring day-old yogurt into a traditional wooden hand churn, or kovan; Sulfer Kazık and Sulta Yalçin churn butter in the kovan. |

It is more generally accepted by food historians that sometime around 5000 BC, nomadic pastoralists living in Central Asia discovered goat’s-milk yogurt and the technique of making it on purpose from a starter culture. This was an extremely important nutritional event, because in hot climates, long before the development of modern refrigeration or the invention of pasteurization, milk went bad within hours or days. Freshly made cultured yogurt contains up to a billion live cells per milliliter of L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus, and this huge concentration discourages the growth of other, possibly disease-causing, bacteria at the same time that fermentation helps preserve the milk and improves its digestibility by breaking down the lactose. For millennia, making yogurt was the only known method of safely preserving milk without drying it.

The definitive Cheese and Fermented Milk Foods by Frank V. Kosikowski confirms that yogurt most likely originated in Central Asia, where nomadic herdsmen, the milk from their animals, high temperatures and the bacteria es-sential for milk coagulation all coexisted.

From Central Asia, the use of yogurt moved south to Persia. From there it traveled west to Anatolia and the Balkan Peninsula, and east to what is now Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. Genghis Khan and his Mongol and Turkmen horsemen, who subsisted largely on mare’s-milk yogurt, fresh horse blood and a slightly alcoholic fermented-milk product called kımız (kumiss), helped introduce yogurt throughout their empire. I have never tasted fresh horse’s blood, but I have recently sampled a commercial version of kumiss from Mongolia, and I can state with confidence that yogurt remains the greatest gastronomic contribution of the Mongols and other nomadic pastoralists of Central Asia to our modern cuisine. Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Turkey, Iraq and Iran continue to be traditional yogurt-producing areas today, and yogurt made from goat’s and sheep’s milk remains an essential ingredient in these countries’ cuisines.

Both ancient and contemporary accounts mention the numerous health benefits attributed to yogurt. It has been used as a sunburn cream, a smallpox preventive, a cure for intestinal disease, to relieve anxiety, treat arthritis and impotence, cure skin diseases, alleviate insomnia and, more recently, as a way to significantly lower cholesterol levels and promote long life. The possible connection between yogurt and human longevity first attracted western interest when in 1913 the Russian biologist Ilya Mechnikof, director of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, noticed that yogurt-eating Bulgars often lived to an impressive old age.

|

| Fresh yogurt butter. |

Of all the Central Asian peoples, it was the Turks who adopted yogurt most widely and put it to the most varied culinary uses. The 11th-century books Diwan Lughat al-Turk (Collection of Turkic Words) by Mahmud Kashgari, a linguistic work, and Kutadgu Bilig (The Knowledge That Brings Happiness) by Yusuf Khass Hajib, a “mirror for princes,” both make numerous mentions of the word yoğurt and give detailed descriptions of yogurt’s various uses by nomadic pastoralists. Yogurt continued to gain wider acceptance and, by the 17th century, Istanbul had more than 500 yogurt shops, all doing business under government regulation. By the time I tasted that first spoonful of yoğurt çorbası in 1972, yogurt had already been a well-established ingredient in Turkish cuisine for nearly a thousand years.

|

|

| From top: Yogurt butter being removed from the kovan; fresh butter being gently kneaded to separate out the buttermilk, or ayran, before shaping the butter. |

Yogurt, also spelled “yoghurt” or “yoghourt,” is known by many different names. It is called katyk or madzoon in Armenia; dahi in India; zabadi in Egypt, Sudan and Yemen; mast in Iran; leben raib in Saudi Arabia; laban in Iraq and Lebanon; and roba in the Sudan. Yogurt is made from many different types of milk, such as sheep, goat, horse, camel, water buffalo and yak. The most unusual-sounding yogurt I came across in my reading was made from donkey’s milk.

Throughout traditional yogurt-making countries, sheep’s and buffalo’s milk are the most highly prized because of their butterfat content, typically around five to seven percent, compared to the 1½ to 3½ percent of cow’s milk. One telltale sign of high butterfat content is the characteristic wrinkled, yellowish cream “crust” on open pots of yogurt commonly sold in the local markets of the Middle East.

In order to watch the traditional yogurt-making process and discuss its various uses, I visited Turkey and met Engin Atkın, a Turkish food scholar, radio personality and co-author (with Mirsini Lambraki) of Two Nations at the Same Table, a comparative gastronomical study of Greek and Turkish cultures. Engin was taught the art of Turkish cuisine by her grandmother, and her recipes have appeared in Food and Wine, Saveur and Bon Appétit. She proved to be an excellent source of information.

From Engin’s childhood in Istanbul, one of her earliest memories was the sound of door-to-door yogurt vendors calling out, “Yoğurtçu!... Yoğurtçu!” as they carried flat pans of creamy yogurt down the streets. Engin Atkın still lives in Istanbul, but during the spring and summer months she runs a traditional Turkish cooking school in a restored Ottoman-era country estate. The residence and school are surrounded by vegetable gardens and fruit orchards in the village of Ula, inland from Bodrum on Turkey’s southwest coast. In the mountains just behind Ula are groups of Yörüks, nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralists whose traditional way of life still revolves around seasonal migrations to and from high mountain pastures with their herds of goats and sheep. Engin has established close friendships with many of the Yörük families, and she uses their milk, yogurt and fresh and dried cheeses at her cooking school.

The Yörük, an Oğuz Turkic people, are the earliest Turkic inhabitants of Anatolia, thought to have originated when Turkmen tribes migrated into Anatolia from the north and mixed with indigenous Anatolian peoples. Their name comes from the Turkish verb yürümek, “to walk,” and they still migrate within well-defined areas, respecting the grazing and water rights of other Yörük families and settled villagers alike.

|

|

| From top: Emine and Hulise Kazık with a grandchild and a pail of fresh goat’s milk. Emine and Hulise strain the goat’s milk; it will be set with rennet to make teleme cheese. |

Shortly after dawn on a crisp sunny day in early spring, Engin and I picked up her friend and culinary mentor, 80-year-old Sulta Yalçin (pronounced yahl-chin). We drove into the hills behind Ula to the home of the Yörük family of Emine and Hulise Kazık. The Kazıks and the other Yörük families we visited in the next several days are semi-nomadic. They sell butter, yogurt and fresh yogurt cheese for a living. By the time we arrived, they had been up since first light, finishing their chores and preparing for our visit.

Immediately after our arrival, the Kazıks rounded up their sheep and goats and their cow and milked them. A fire was kindled, and before long they had a pot of steaming hot fresh cow’s milk. Once it had cooled to the proper temperature, a yogurt starter (yoğurt mayası, “yogurt yeast”) from the previous batch was stirred into the milk. The pot was wrapped in a blanket and placed by the hearth to set, or “strike,” çalmak, as the Turks say. As the live yogurt cultures in the pot began to incubate, Engin, Sulta Yalçin and the Kazık women talked about various uses of yogurt in other parts of the Middle East.

In Iran, people drain the whey from sheep’s-milk yogurt and then dry it into spherical balls of chalk-white hard cheese known as kashk, a high-protein food with an indefinite shelf life, ideal for nomadic herdsmen. Kashk is typically used to add flavor to soups and other dishes. Iranians also produce a beverage called doogh, which is a dilute, spiced yogurt drink that’s usually carbonated when sold in bottles.

Kurut, popular in Afghanistan, is another dried-yogurt product, similar to kashk. Like industrial powdered milk, the pebble-sized balls of kurut are reconstituted by mixing with water and are then used either as a drink or as an ingredient in sauces and soups. According to The Oxford Companion to Food, the word kurut is derived from the Turkish kurumak, “to dry.”

In Lebanon, yogurt is sometimes strained through a cloth to remove all the whey, then hand-rolled into small balls the size of ping-pong balls, known as labne. The labne are air-dried for several days until somewhat firm and can then be stored in containers of olive oil for a year or more without spoiling. The texture and consistency of labne is similar to American cream cheese; it is most frequently used as a spread on pita or rustic multi-grain mountain breads.

|

|

| From top: Ayran left over from butter-making being boiled up in preparation for making çökelek, a salty, dry yogurt cheese often used to fill börek. Sulfer Kazık straining the ayran, now salted, to make çökelek. |

Torba yoğurdu means “sack yogurt” in Turkish, the torba referring to the sack through which the whey is drained for a few hours. Also known as süzme (“strained”), it has a consistency similar to sour cream and is also used on bread, as well as in yoğurt çorbası and other soups.

Engin also told me about kaymak, the thick layer of cream atop high-quality Turkish yogurt. In richness and consistency, kaymak is very similar to the famous Devonshire clotted cream of England, but according to Engin the very best kaymak comes from sheep’s milk. It is made by heating the milk very slowly, allowing it to thicken while most of the cream rises to the surface, then gently stirring in the yogurt starter culture. Once set and chilled, the kaymak layer is gently rolled off the top of the yogurt and served with baklava or other syrupy desserts. Kaymak is often used as a filling for the sweet the Turks call künefe and the Arabs qata’if.

Over the next two days we also made butter from yogurt, a drink called ayran, various soups and sauces, and several fresh and dried cheeses, all from yogurt. Butter came first. The Kazıks now use an electric churn, but Sulta Yalçin had brought along a churn made from a hollowed-out tree stump, and she used this family heirloom, called a kovan, to demonstrate the traditional technique. The kovan itself had been made by drilling a hole down the center of the meter-long stump and enlarging it with a smoldering fire until a cylindrical tube of the required wall thickness was achieved.

Cow’s-milk yogurt from the previous day was poured into the kovan and churned with a long-handled perforated wooden plunger for about 45 minutes. At this point, the butterfat had come together in small globules that were a rich yellow color. The side of the kovan was tapped with the shaft of the plunger to bring the rest of the coagulated butter particles to the surface. Then the butter was scooped out with a wooden spoon and pressed by hand to remove all of the leftover liquid.

|

| Crumbly, salty çökelek, mixed with a little za‘tar spice. |

Ayran (aye-rahnn), the liquid which remained in the churn, is what we know as buttermilk, thick and full of milk solids. Sulta Yalçin explained that if the yogurt is allowed to sit for three to four days before churning, the butter will be better, but the ayran will be thinner and less rich.

Ayran is also the name of a popular and refreshing yogurt drink; Emine Kazık made some by taking a pitcher of fresh buttermilk from the churn and mixing it with three-quarters of a pitcher of cool water. She added what looked like several teaspoons of salt and a tablespoon or more of fresh crushed mint, beat the ingredients together in a large bowl and poured the resulting frothy drink into glasses. It had a rich, fresh milk flavor.

In Turkey, ayran is frequently made at home, but it is also served in restaurants and cafés and is available from street vendors in the larger cities. In India and Pakistan, a drink called lassi is made from yogurt and water. It is often blended with sugar and fresh fruit, such as mango, but the salted version of lassi is very similar in taste, texture and flavor to ayran. According to Engin and Sulta Yalçin, the large quantity of calcium in ayran makes one feel contented, tired and sleepy. Ayran is typically drunk after eating fish; and kebabs should always be accompanied by ayran.

|

|

|

| From top: A Yörük couple, Ari and Hüriye Bilge, in the hills near Bodrum. Yörüks migrate to and from well-defined mountain pasturelands that “belong” to their group; they are thus technically “transhumants” rather than nomads or semi-nomads. Sulfer and Mustafa Kazik. Fresh buttermilk (ayran) separated from the kneaded butter. |

With the rest of the ayran left in the churn, Emine showed us one other way to use this yogurt by-product. Rekindling the wood fire, she brought the ayran to a boil and then added a generous handful of salt. Small stiff curds, the size of cottage-cheese curds, formed and floated to the surface. She took the pot off the fire to cool slightly before pouring the watery liquid and curd into a cotton sack. The sack was hung from a tree branch for two hours to drain and then a large flat stone was placed on it to extract the last bit of moisture. The resulting salty cheese, quite dry and crumbly, is called çökelek (pronounced chirk-eh-lek), and tastes similar to a very dry feta cheese. Thanks to the salt content, it will last 15 days fresh or up to a month in a refrigerator. Çökelek is added to a variety of Turkish dishes for flavor and texture, especially in the filling for börek, which—at least in the countryside—is a stuffed, folded, thin flatbread that looks something like a folded thin-crust pizza. (A city börek is made of strips of paper-thin yufka dough stuffed, folded flagwise into triangles and deep-fried.)

During a break in these demonstrations, I asked Engin and Sulta Yalçin about the yoğurt çorbası that I had eaten in Erzurum more than 35 years earlier. They confirmed that it is one of the regional specialties of Erzurum, duplicated but rarely improved upon in other parts of the country. There is something unique about the yogurt in Erzurum which accounts for the flavor, they said. The traditional recipe calls for hulled wheat and fresh cilantro to be added to the chicken stock, flour, eggs and yogurt cream, but rice and dried mint are frequently substituted for the first two ingredients.

On our last day with the Kazık family, they laid out lunch on a rough wooden table shaded by a grape arbor. The table was covered with the fruits of their labors, including a sampler of yogurt dishes. There was freshly baked pide (pita) bread, sweet unsalted butter from yogurt, sliced tomatoes from the garden, fresh sheep’s-milk yogurt, a yogurt sauce mixed with minced green onions, chili and paprika; a fresh, fruity olive oil;

|

| A frosty glass of ayran made from yogurt, water and salt. |

a beet salad with slivered green peppers, pine nuts and dill mixed with yogurt; glasses filled with frothy ayran; a pilav; crisp cucumber slices; black olives; skewers of succulent and spicy lamb kebabs; cacık (ja-jick), a cold soup of cucumbers, ayran, garlic, dill and, in this case, ground wal-nuts; and a soft goat’s-milk yogurt cheese seasoned with wild thyme, roasted sesame seeds and sumac and covered with olive oil. For dessert we drizzled wild bee honey over kaymak.

After lunch, we had a final glass of tea, thanked our hosts once again and drove back to Engin’s summer house in Ula for a nap. Earlier in the day, Engin and I had made plans to take Sulta Yalçin to the weekly open-air market in Ula for a plate of her favorite künefe. But after such a sumptuous and satisfying meal, we agreed that the visit to the pastry-sellers of Ula, or further sampling of yogurt in any of its various forms, would have to wait for another day.

|

Eric Hansen (ekhansen@ix.netcom.com) is a free-lance photographer and the author of numerous books, including The Bird Man and the Lap Dancer (2004), Orchid Fever (2001), Motoring with Mohammed (1992) and Stranger in the Forest (1988). |