|

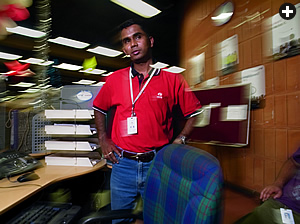

| From Bangalore, employees at CL13L, a “Business Process Outsource” (BPO) center, help their company’s client customers in North America around the clock. |

a unit of General Electric—

an international company engaged in

manufacturing, healthcare, finance and

energy—set up a series of help desks that

its customers in the US and Canada could phone for queries about their bill payments. It was a routine business decision—except that the help desks were not in the United States but in Gurgaon, a prawling suburb outside India’s national capital, New Delhi.

To staff the desks in India, the subsidiary, GE Capital International Services Ltd. (GECIS), recruited recent Indian college graduates who were proficient in English. The average starting salary they offered was equivalent to $160 to $180 a month—about as much as an engineer might earn in India, and thus an attractive salary for recruits with basic degrees in arts, commerce or sciences.

GE was hardly alone in its move. American Express, British Airways, Scope International and dozens of other companies began what became a virtual migration

of customer care, invoice processing and other administrative functions to India. It was the beginning of the global business now known as “business process outsourcing,” or BPO, whose 28-percent growth rate makes it “one of the fastest growing sectors in the country,” says Ganesh Natarajan, deputy chairman and managing director of Zensar Technologies Limited, a BPO firm in Pune, in the western state of Maharashtra.

|

| Downtown Bangalore |

More than any other industry, BPO, which now employs more than 700,000 people, has placed India’s services sector on the global map, and it has quickly become symbolic of India’s upward mobility as

an economic power of the 21st century. Its growth, over less than a decade, has also powered the “second wave” expansion

of Indian BPOs to more than 25 different foreign countries, including Guatemala, Mexico, Finland, Philippines, Ireland, Malaysia, China and Middle Eastern nations. Shashi Ravichandran, head of corporate affairs for Scope International & Standard Chartered Bank’s branch in Mauritius, explains that this ensures that offshore centers are as close to customers as possible.

According to one industry study, at the end of March 2008 India’s BPO operations booked $10.9 billion in revenue and accounted for approximately 40 percent of the global BPO industry. Another study named India’s leading competitors: China, Canada, Russia and Eastern European nations such as Romania.

|

| Banglalore’s BPO and electronic technology boom has made the city synonymous with India’s economic rise—and ubiquitous construction sites. |

The impetus to outsource business operations to India has roots both in the Indian education system and in the

nation’s 1994 privatization

of formerly state-owned telecommunications

industries. Proficiency

in English is widespread in India’s major urban

centers, and the country’s strong college-level education system produces a steady stream of job-hungry graduates. Then, in 1999, when further deregulation allowed international calls to be routed through the Internet, competition cut rates enough to make it attractive for transnational businesses to subcontract (“outsource”) labor-intensive office functions to India, where payrolls were 14 to 25 percent of those in western countries—despite the increase of Indian BPO salaries to between $400 and $700 by 2003.

“A young and skilled workforce, adept at learning new technology,

and supportive government policies together led to the growth of this

industry,” said Natarajan in an e-mail interview. In early 2008, Natarajan was elected chairman of the industry body, the National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM).

|

| At CL13L, Angeline George stands and listens to a caller. |

By 2003, there were almost 110,000 young Indians working in BPO companies. Roughly a quarter of them were employed by multinational corporations operating “captive units”—centers dedicated to serving a single firm—or in independent BPOs that also served a single firm, and the rest worked for contractors who served multiple clients. Widely referred to in industry parlance as “associates,” BPO workers transcribed medical data, processed bills and credit-card payments and offered voice-based customer support, primarily to customers in the US and UK, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

|

| Rakesh Sadandanda helps a customer online. |

Further change came quickly as companies expanded their agendas to include higher-value tasks in accounting, engineering, publishing, sales and marketing, transaction handling, management and research in sciences and mathematics, many of which required advanced degrees—qualifications which companies found in abundance. “India became a destination that offered an advantage in skills and not just in cost,” says Ravichandran. Animation studios like Walt Disney, mgm and Warner Brothers began to outsource clean-ups and modeling. In response, some BPO’s began to morph into “knowledge process outsourcers,” or KPOs. “Organizations across the world now realize the value that India offers and are moving complex, analytical and mature processes to the country,” says Natarajan.

With that move, some multinational corporations shed their captive units to create independent BPO units that could compete for business from multiple clients against the profusion of independent, India-based firms. Seven years after founding its first help desks, GECIS divested 60 percent of its holding to form Genpact, which is now India’s largest BPO company, with more than 34,300 employees and annual revenues at the end of March 2008 of $823 million. (India’s fiscal year begins in April.)

|

| “Old” and “new” technologies run side by side—sometimes literally—in Bangalore. |

As the industry matures, still more services arise: “Legal process outsourcing,” or LPO—legal and copyright research and drafting of such documents as patent applications—is now the second-fastest growing segment of the global BPO industry, rising from about $80 million worth of business in 2006 to approximately $4 billion by 2010, according to the 2007 Black Book Survey by the Brown-Wilson Group. India, which produces over 200,000 lawyers every year and employs more than 12,000 of them in its nascent LPO sector, is expected to slice off a large piece of that pie. Elsewhere, in downtown Bangalore, math majors crunch data at Mu-Sigma, an analytics firm that counts pharmaceutical giant Pfizer among its clients.

|

| India's top BPO Cities. |

Indian BPO firms now have the base for their own global footprint. Companies such as Zensar have sales and operations centers in China, the Asia–Pacific region and Japan, the US, UK, Europe and the Middle East. Such global operations also allow the companies to serve non–English-speaking clients. For example, when Scope International bagged a BPO contract from Taiwan, its center in Chennai (India) hired Chinese-speaking employees locally to carry out the work.

“In Chennai, the only place we could look for such people were Chinese-run restaurants and beauty parlors,” says Ravichandran.

By 2012, the global market for all types of BPO services is expected to multiply by a factor of seven to $220 billion, and the Indian slice will keep pace, says Natarajan, rising to more than $50 billion and employing, he expects, more than triple the current number of employees.

However, the spectacular growth has slowed this year. Addressing the World Economic Forum’s India Economic Summit in November, the deputy chairman

of the country’s Planning Commission, Montek Singh Ahluwalia, predicted that “the Indian economy will grow between seven and seven and a half percent in the current fiscal year—down from the 9.2% growth of 2007 but higher than the growth rate in 2004.”

NASSCOM, the industry body, expects growth of the BPO sector to decrease to 22 to 23 percent, down from the 28 percent posted in 2007.

In response to this softening, salary hikes across the BPO industry are expected to drop into the nine- to ten-percent range over the next four years, down from an

average growth rate of 14 to 15 percent

annually since 2003, according to Hewitt Associates. This, says Ravichandran, was to be expected, as “it is not unusual for a sunrise sector to initially pay more than other industries, but as the BPO sector stabilizes, which it is doing now, I expect that salaries will also stabilize.”

|

In addition to managing a breakneck pace of change, a top challenge for BPOs is controlling increasing costs. There is high employee turnover, largely because everyone has to put in time on the graveyard shift. Some of the solutions are uniquely Indian: For example, weak public transport services often make it necessary for BPO companies to offer workers free, private commuting, and at many firms they have access to free meals at the workplace. At Scope International, perks include flexible hours for housewives and new mothers, yoga programs and aerobics and health camps, yet industry-wide, three out of 10 BPO employees quit each year.

Industry watchers believe the next growth opportunity for BPOs in India will take place close to home with the emergence of domestic business process outsourcing. “In areas like telecom and insurance and

financial services this is already happening,” says Sanjay Anadaram, managing

director of Jumpstartup, a venture-capital fund that invests in technology. As the

Indian economy grows, more domestic companies will hive off routine processes, increasing today’s domestic business process value of about $1.6 billion to some $15 billion or more in the next five years, according to the Everest-NASSCOM report.

Abroad and at home, it appears that the economic role of outsourced business functions in India will only grow stronger.

| The Virtual Immigrant exhibition was shown at the Fine Arts Center Main Gallery, University of Rhode Island, October 20 through December 6, 2006. All photographs in this article by Annu P. Matthew are interpretations of lenticular prints, original size 114 x 152 cm (45 x 60"). © 2006 Annu Palakunnathu Matthew. Reprinted with permission. |

|

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew (www.annumatthew.com) is associate professor of art (photography) at the University of Rhode Island. In 2007 she was awarded a MacColl Johnson Fellowship in Visual Arts; her work is included in BLINK (Phaidon, 2002), which celebrates 100 contemporary photographers. She is represented by Sepia International Inc. in New York and Tasveer Gallery in Bangalore, India. |

|

Archana Rai, a business writer based in Bangalore, has been

reporting on economic issues for over 15 years. Her articles have appeared in India’s premier business publications, including The Economic Times, Business India, Outlook Money and Mint. She can be reached at archanarai@hotmail.com. |

|

David H. Wells (www.davidhwells.com) is a free-lance documentary photographer affiliated with Aurora Photos (www.auroraphotos.com) who specializes in intercultural communications. He has received two Fulbright fellowships to India. |

This article appeared on pages 24-31 of the January/February 2009 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for January/February 2009 images.