|

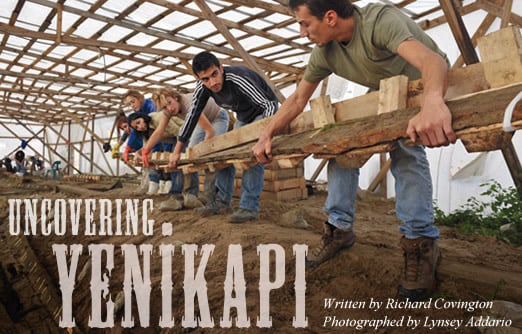

| Inside one of the site's temporary sheds, a splint helps a waterlogged plank keep its shape as archeologists and students dismantle one of Yenikapi's 32 shipwrecks found to date. |

Outside, the brilliant June sunshine beats down mercilessly on Turkey’s largest city. But the shed is kept cool by a fine mist sprayed from suspended hoses; the mist keeps the exposed wood moist and prevents it from shrinking. Ever so gently, the five women and four

men slide a three-meter (10'), L-shaped frame beneath a waterlogged plank too fragile to be lifted directly. One of them gives the go-ahead and they raise the plank in unison, then place it into a wooden case, where it rests on a pine support specially designed

to ensure that the plank keeps its shape. Later, the case containing the plank and the support will be lowered into a concrete-lined pool of slowly circulating fresh water. Eventually, after conservation and reassembly, the ancient ship, one of 32 uncovered so far in the run-down Istanbul neighborhood of Yenikapi, will likely go on display in a new museum dedicated to what many experts are calling the greatest nautical archeological site ever discovered: a vast excavation covering more than 58,000 square meters (nearly 625,000 sq ft), the equivalent of 10 city blocks, on what was once the edge of medieval Constantinople.

|

| Standing among piers of what was for nearly 900 years a hub of international shipping, Ufuk Kocabaş is field director of the nautical arche- ology team from Istanbul University. |

“It’s the most phenomenal ancient harbor in the world, and it’s absolutely revolutionizing our knowledge of ship construction during Byzantine times,” declares Sheila Matthews, who is unearthing and researching eight boats for the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University. “There is no other place that has so many shipwrecks in context with one another.” From brick-transport vessels to round-hulled cargo boats 19 meters (60') long and small lighters used to off-load larger ships, Yenikapii is yielding up the full gamut of ships that once busied one of the most active harbors of the middle ages. Among the site’s astonishing prizes are the first Byzantine naval craft ever brought to light.

Lost for more than 800 years, Yenikapii’s fourth-century port dates back to Theodosius i, the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and western portions of a unified Roman Empire, and

it was active until around 1200. Trading ships converged here from the Mediterranean, the Danube River and the Black Sea. Spices, ivory and jewels came from India; silks from China; carpets, pearls, silk and woolen weaving from Persia; grains and

cotton from Egypt; as well as gold, silver, fur, honey, beeswax

and caviar from Russia. Marble, timber and brick were imported to build and furnish the booming Byzantine capital, while textiles, pottery, wine, fish, oil lamps and metal items were exported to finance the growth. Pilgrims passed through on their way to Makkah and Jerusalem. Transported in cargo ships, pirate captives and enemy prisoners from Africa, Central Europe and Russia arrived for sale in the lucrative local slave market. Among Yenikapi’s artifacts discovered to date are plates from the Aegean, oil lamps from the Balkans and amphorae from North Africa, along with a profusion of glass, metal, ivory and leather—all evocative remnants of a far-flung mercantile empire that had Constantinople at its center.

Lost for more than 800 years, Yenikapii’s fourth-century port dates back to Theodosius i, the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and western portions of a unified Roman Empire, and

it was active until around 1200. Trading ships converged here from the Mediterranean, the Danube River and the Black Sea. Spices, ivory and jewels came from India; silks from China; carpets, pearls, silk and woolen weaving from Persia; grains and

cotton from Egypt; as well as gold, silver, fur, honey, beeswax

and caviar from Russia. Marble, timber and brick were imported to build and furnish the booming Byzantine capital, while textiles, pottery, wine, fish, oil lamps and metal items were exported to finance the growth. Pilgrims passed through on their way to Makkah and Jerusalem. Transported in cargo ships, pirate captives and enemy prisoners from Africa, Central Europe and Russia arrived for sale in the lucrative local slave market. Among Yenikapi’s artifacts discovered to date are plates from the Aegean, oil lamps from the Balkans and amphorae from North Africa, along with a profusion of glass, metal, ivory and leather—all evocative remnants of a far-flung mercantile empire that had Constantinople at its center.

The port was uncovered in November 2004 during excavations for a 78-kilometer (48-mi) rail and metro network that will ultimately link Europe and Asia via a tunnel under the Bosporus. Constructed of submersible sections, the tunnel will run beneath 56 meters (180') of water and 4.5 meters (15') of seabed, making it the deepest tunnel in the world. The need is acute: The two bridges currently crossing the Bosporus are jammed, and the

existing subway, consisting of one line and six stations, is inadequate for a city

of more than 12 million inhabitants.

|

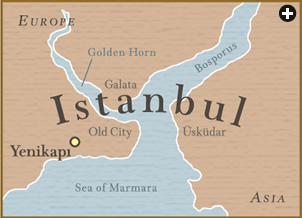

| The remains of the port were discovered in 2004 when excavation began for the $4-billion Marmaray urban transit system’s hub, which was then redesigned to accommodate the 10-square-block dig site. The ancient port today lies inland by about a kilometer—one of the reasons it lay undiscovered for so long. |

Amid this burgeoning megalopolis, Yenikapi is slated to become the biggest transportation hub in the entire country. Metro, light rail and passenger trains will converge here in a sprawling development of shopping malls, office towers and residential complexes rising next

to an archeological park that contains the remains of a fifth- or sixth-century lighthouse and a 12th- or 13th-century Byzantine church.

But until then, the site is a hive of

activity as more than 800 archeologists, engineers and laborers in bright orange vests race to finish excavations. Despite pressure from the transit authorities to wrap up the dig, however, archeologists refuse to set a deadline for completion of their work. “Every construction site, be it for a small building or a multi-billion dollar megaproject like this one, is a window on the past that is opened only briefly,”

explained Ismail Karamut, the head of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, to Archaeology magazine. “A window of this size may not be open in Istanbul for many decades to come.”

According to Ufuk Kocabaş, the archeologist directing the

Istanbul University team, the excavations should be finished by early 2010. Documentation, conservation, and reconstruction of the ships will then continue for many years more, he predicts.

A developing country like Turkey deserves a great deal of credit for putting archeology ahead of the urgently-needed transit project and sacrificing millions of dollars in delays, argues Cemal Pulak, a Turkish–American professor heading up the Texas A&M team. “Colleagues visiting from Europe and the us are amazed,” he remarks. “They tell me that in their countries they are handed a deadline and told to simply do the best they can.”

|

|

Above: Near the excavated quays is a stone wall, above, that Kocabaş and others believe was part of the earliest city wall laid out by Constantinople’s founder, the Roman emperor Constantine i, in the fourth century, more than 50 years before Theodosius i constructed the harbor.

Below: Of the 32 shipwrecks found so far, 17 have been excavated, and some are as much as 40-percent intact. |

Despite his gratitude that Turkish cultural authorities are fighting hard to preserve the site, Pulak wishes that the operation—large as it is—had been expanded beyond the central part of the harbor to encompass more of the quays, granaries and storage buildings that he suspects lined its perimeter. Such an extension of the dig “would have required a lot of convincing and maneuvering,” he admits, “but it would have helped enormously in

understanding the huge harbor and its impact on the economy and life of Constantinople.”

The Yenikapi dig has drawn academics from around the world. In addition to the team from Texas A&M, scholars from Cornell University, Istanbul University, Hacetteppe University in Ankara and Tel Aviv University in Israel are contributing to the research and analysis of the finds. Turkish archeologists are consulting with ship museums in Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Holland, Spain and the uk about the creation of a new local museum. Next October, Istanbul will host an international symposium

on nautical archeology and ancient ships.

By that time, the Yenikapi excavation should be nearing completion, and the city’s new transit scheme will be moving into high gear. All told, the $4-billion Marmaray (a name that joins the Marmara Sea to ray, the Turkish word for “rail”) train and tunnel project and the coordinated metro lines will also rebuild 37 stations above ground and three new ones below ground. The network will be capable of transporting 75,000 passengers per hour. Engineers predict that when the system is completed in 2012—two years behind schedule—the percentage of trips by public transport will jump from an abysmal 3.6 percent at present to 27.7 percent, a figure that would put Istanbul at number three

in the world in public transport, behind Tokyo (60 percent) and New York City (31 percent).

As if juggling the port excavations and the tunnel-transit project were not enough, engineers also have to contend with the near-certainty of a major earthquake from the 1200-kilometer-long (745-mi) North Anatolian Fault, which runs in an east-west direction only a few kilometers south of the city. Since the year 342, a dozen massive tremors have each left more than 10,000 dead. In 1999, two together killed 18,000 people. Seismologists calculate that there’s a

77 percent probability of a quake of 7.0 magnitude or higher occurring in the next 30 years.

Engineers insist that the tunnels will be able to withstand a 7.5 quake, bigger than the one that destroyed much of Kobe, Japan in 1995. Nonetheless, Geoffrey King, director of the tectonics lab at the Institut de Physique

du Globe in Paris, told Wired magazine, “I wouldn’t like to be in such a tunnel during an earthquake.”

About 2400 meters (1.5 mi) northeast of Yenikapi,

the new metro tunnel runs beneath the city’s principal

historic district, the Sultanahmet area, home to Topkapi Palace, where sultans ruled the Ottoman Empire for four centuries, the sixth-century Hagia Sofia museum (formerly a church, then a mosque), the Blue Mosque and other landmarks. Karamut insists that the tunnel will lie deep enough to avoid risk to the ancient sites.

|

| Archeology students mark planks before they are removed for conservation and eventual reassembly and museum display. |

Like Rome and Athens, both ancient cities that have built subways in modern times despite frequent delays to explore buried antiquities, tunneling for the metro (and a parallel dig

beneath the Four Seasons Hotel in Sultanahmet) in 2800-year-old Istanbul has unearthed numerous other treasures, including what is believed to have been the fifth-century main doorway

of the Imperial Palace. This monumental bronze gate, some six meters (20') tall, was uncovered near the Blue Mosque, along with Byzantine mosaics, frescoes, and portions of a 16-meter (52') street, sewer system and hammam, or Turkish bath. So far, the later discoveries have not caused engineers to alter the subway tunnel route, however, and it is uncertain what will happen to the ruins that have recently emerged in Sultanahmet.

Meanwhile, the gargantuan dig

at Yenikapi continues to disgorge

an eclectic mix of the marvelous

and the mundane. Apart from the

32 watercraft dating from the seventh to the 11th centuries—including four naval galleys—archeologists have dug up more than 170 gold coins, hundreds of clay amphorae

for wine and oil, ivory cosmetics cases, bronze weights and balance scales, finely-wrought wooden combs and exquisite porcelain bowls. They’ve recovered bones of camels, bears, ostriches, elephants and lions—probably imported from Africa for entertainments at the Hippodrome, suggests Kocabaş. Some

15 human skulls retrieved from a dry well may have belonged to executed criminals. Iron anchors have been recuperated, objects so highly prized in medieval Byzantium that they are noted in the dowry records of wealthy merchants’ daughters. The oldest find is an 8000-year-old Late

Neolithic hut containing stone tools and ceramics—the earliest settlement ever located on the city’s historic peninsula. One particularly mind-boggling find, discovered aboard a ninth-century cargo ship, was a basket

of 1200-year-old cherries nestled next to the ship’s captain’s ceramic kitchen utensils—a cooking grill, hot pot, pitcher and drinking cup—as if waiting for the ancient mariner’s

imminent return.

“No, I didn’t taste them,” laughs Kocabaş. “But I did think about planting a few pits to see if they would sprout.” (Kocabaş rejected the notion when he realized both the fruit and the pits had turned to carbon.) The site’s ships, bones and artifacts (and cherries) were so

unusually well preserved, he maintains, because silt from the Lykos River and sand from the Marmara Sea quickly covered over the wrecks.

After a fortifying lunch of stuffed grape leaves and meat-filled eggplant at a busy local eatery, Kocabaş and Metin Gökçay, site chief from the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, take me along

to explore the first portion of the harbor brought to light. It is also the oldest part of the port, a flashpoint alerting local archeologists to the unique historical significance of a site that had nearly been bulldozed.

En route, we pass dozens of laborers pushing wheelbarrows

of powdery, pale-brown dirt up wooden or earthen ramps crisscrossing the immense six-meter-deep (20') pit. Next to a cluster

of modern-day shipping containers converted to field offices and conservation labs are hundreds of blue plastic milk crates stacked and loaded with amphorae, pottery fragments and animal bones. In the distance, several long white sheds shelter ships. Beyond tall metal fences enclosing the site stand rows of two-story shops backed by high-rise apartment blocks.

Arriving at a quiet, overgrown area on

the western fringes of

the site, we push aside branches of fig and bamboo to inspect massive limestone blocks. “These were the original quays,” says Kocabaş. “You can see the notched holes hewn out of the rock for tying up the boats.” Next to the quays is a stone wall that Kocabaş, Gökçay and others believe was part

of the earliest city wall laid out by Constantinople’s founder, the Roman Emperor Constantine i, in the fourth century, more than

50 years before Theodosius i constructed the harbor. Researchers

at the dendrochronological laboratory at Cornell University have confirmed that wooden supports from the 53-meter (170') portion

of the wall that has been dug out date from the fourth century,

he explains. Even though the wall and quays lay only a meter (39")

underground, they remained hidden and forgotten for centuries.

Initially, the area was to be part of the train and metro station, but when the ancient remains were found four years ago, they were declared off-limits and plans for the station were changed

so as to leave the historic monuments intact.

|

| According to Metin Gökçay of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, the site has to date yielded more than 16,000 “quality objects.” Each is first cleaned and catalogued on site. |

In the broiling heat, a merciful breeze flutters laundry hanging from the tenement windows overlooking the site as we clamber over the wall to survey the remains of tannery pits and a

late Byzantine charnel house. “Look there,” directs Gökçay, as

he points to a vaulted stone tunnel leading straight to the sea. “That’s a secret passageway so you could slip out of the harbor undetected.” The archeologist speculates that the tunnel led to a former palace on a hill behind the harbor and was also used in the other direction, to smuggle goods into the city to avoid customs duties. Later, Texas A&M researcher Matthews suggests, more prosaically, that the tunnel was used for sewage or drainage.

From here, you can picture how the harbor took shape. A stone breakwater, now gone, led from the quays out into the sea, then curved east to form

a barrier protecting the harbor, Gökçay explains.

Sediment from the Lykos, which emptied into the port, was also caught by the break-water. But instead of flowing out to sea, the alluvial soil gradually backed up, silting up the harbor.

By the 12th century, the port was so shallow it was only used by small fishing boats. Four centuries later, the once-bustling harbor was a memory. A 16th-century account by Pierre Gilles, a natural historian dispatched by the French king François i to acquire manuscripts in what had become the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, describes the former Byzantine port as a garden spot covered with vegetable plots watered by waterwheels known as norias.

Leaving the western wall, we trudge across the kilometer-wide (1100-yd) site to

the eastern edge of the port, to the lighthouse that dates to the fifth or sixth century—or rather to the five-meter (16') marble and limestone base of the lighthouse. On the way, we pass the vestiges of stone walls outlining a 12th- or 13th-century church, one

of two churches found close to the edge of the filled-in harbor.

All around the former lighthouse, earth has been scooped out to reveal its base and the ground beneath it, opening a cross-section of geological strata. Embedded in a lower zone is a thin black band running horizontally a foot or so above what had been the bottom of the ancient harbor.

“That’s a tsunami line,” Kocabaş explains. “It shows that a major earthquake occurred here, probably—based on the objects we dated in the strata—around the middle of the sixth century.”

A jumble of potsherds, wood pieces and other artifacts were churned up by the cataclysm, he says, adding that entire camel and horse skeletons lay crushed in the debris.

According to geological evidence detected elsewhere, at least one more tsunami, or perhaps only a ragingly destructive tempest, occurred around the year 1000. Judging from the violent way some of the boats appear to have been hurled into one another, Kocabaş concludes that several ships were sunk in that storm.

What was no doubt a tragedy at the time, however, has proven a boon to archeologists. Because the waves hit the port so quickly, anchors and cotton ropes sank in place and were quickly preserved beneath silt and sand. “It was an exceptional stroke of good fortune because it showed us for the first time exactly how Byzantine mariners rigged their anchors,” he observes.

What was no doubt a tragedy at the time, however, has proven a boon to archeologists. Because the waves hit the port so quickly, anchors and cotton ropes sank in place and were quickly preserved beneath silt and sand. “It was an exceptional stroke of good fortune because it showed us for the first time exactly how Byzantine mariners rigged their anchors,” he observes.

After Gökçay leaves to return to his site office, Kocabaş leads me to a nearby excavation shed. “You’re in luck,” he announces, opening the flap to reveal a magnificent wreck, a Byzantine galley with most of its original 30-meter (95') length and half its nine-meter (30') width remaining. “Finding longboats like this is

extremely rare, and in fact, we just finished opening the surface today. Yesterday, half the ship was covered with sand.” He bends down to point out where the oars had been placed.

“This ship had 50 oarsmen,” explains Kocabaş, “so it was in-

credibly fast and light.” Despite its length, the narrow craft was nonetheless too small to engage in battle, so the archeologist speculates it was probably used to reconnoiter enemy ships. No dromons—Byzantine warships generally twice as long and with

as many as 100 oarsmen—have so far been located at Yenikapi,

according to Kocabaş.

“Just feel how hard and well-preserved the wood is,” he continues, allowing me a brief touch. That nemesis of nautical archeologists, the rapacious Teredo navalis mollusk, bores holes into wrecks in the open sea, ultimately turning their planks and beams into crumbly sponge. Yet Teredo did little damage at Yenikapi because the fresh-water inflow from the Lykos river kept them away. Apart from the four galleys, archeologists have so far excavated only about 17 of the 32 ships that have been found. Some six ships, each shorter than 11 meters (35'), were used for fishing and moving goods locally. Around 10 boats between 11 and 19 meters long ranged greater distances, trading around the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. The larger of these boats also sailed the Mediterranean, bringing grain back from Egypt. The biggest ship that has appeared so far is

40 meters (130') long and

dates from the sixth or seventh century. “We nicknamed it Titanic,” quips Kocabaş.

Most of the vessels were hewn of oak, chestnut and pine from the Marmara region, and constructed with iron nails and wooden dowels, he says. Galleys were rigged with triangular lateen sails made of cotton, linen and hemp; cargo ships had square sails of similar material. To make the crafts seaworthy and stop leaks, their planks were caulked with a glue-like substance made of pine resin and oakum. None of the longboats and only a few of the longer cargo ships had decks, according to Kocabaş.

Back in the shipping container that serves as Gökçay’s office, the pair run me through a computer presentation of some of Yenikapi’s greatest archeological hits. Apart from literally millions of ceramic shards, there are, notes Gökçay, some 16,000 “quality objects,” artifacts that illuminate Byzantine life and the expansive trade that made the harbor a thriving entrepôt for a good part of eight centuries.

There’s a fourth-century marble statue of Apollo; a Roman copy of an original work by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles; a gold coin bearing the image of Aelia Pulcheria, sister and regent of fifth-century emperor Theodosius ii; a seventh-century ceramic oil lamp with a cross; an undated ivory carving of the Virgin Mary; an undated marble statue similar to figures on the Pergamon altar, a Hellenistic masterpiece removed from that ancient Greek city in northwest Anatolia to Berlin in the late 19th century. There are board games, dice, ceramic toy ships, 11th-century ceramic cups decorated with bas-relief images of faces with Mongolian features, perhaps from Central Asia, and an enigmatic lead tablet with Hebrew writing that Kocabaş theorizes was used to cast out evil spirits.

|

|

Top: Recording the team’s finds, Texas A&M graduate student Rebecca Ingram draws a life-size sketch of an oil lamp on a plastic sheet while a colleague photographs another artifact.

Above: Ingram and nautical archeologist Sheila Matthews work on planks that are covered in plastic to prevent evaporation, which can crack the wood. Yenikapi, says Matthews, is “revolutionizing our knowledge of ship construction during Byzantine times.” |

The delicately-fashioned sole of a wooden shoe bears a Greek inscription on the instep that, according to Gökçay, roughly translates: “Wear this shoe in health, lady, and step into your happiness.” Intrigued by the handiwork, the museum archeologist scoured some 20 villages in Central Anatolia to seek out cobblers and carpenters using similar traditional woodworking methods. Among the craftsmen he encountered was an 81-year-old carpenter still turning out wooden forks, spoons, plates—and shoe-soles—employing techniques that have changed little since Byzantine times. None of

the modern shoes, however, bore inscriptions.

Among the tools unearthed are peculiar drills with iron bits set into wooden cylinders. Kocabaş explains that a horsehair bow-string was looped around the cylinder and the bow was moved rapidly side

to side to turn the iron bit—

another woodworking technique that can be seen in Turkey today.

Once the documentation, conservation and reconstruction process is well under way, the archeologist plans on fabricating a replica of one of the Byzantine ships. “Building a replica, using saws, axes and other tools similar to the ones the Byzantines used, is the

best way to get an authentic, hands-on notion of boat construction,” he says. How to make the ship symmetrical and correct mistakes; how to fit the frame and planks together; how to shape a keel that steadies the craft but doesn’t slow it down; how to seal the hull against leaks—all of these technologies will be revealed, he hopes.

Then, the ultimate pay-off will be actually taking the replica out on the water. Visiting the waterfront Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark in June 2007, Kocabaş accompanied a curator on a late-afternoon spin aboard a replica of a Viking ship, taking an exhilarating turn rowing beneath the billowing canvas sail.

“It was fantastic,” he recalls. “A total dream.”

Texas A&M’s Sheila Matthews similarly dreams of piecing

together a functioning replica, a spanking new double of one of the waterlogged hulks she confronts daily at the dig site. But first, she says, comes the less glamorous reality.

When I meet her under one of the site’s preservation sheds, the red-haired archeologist is ankle-deep in mud, carefully lifting a 120-centimeter (4') plank from a seventh-century cargo ship with the help of a pair of student-assistants. The boat lies alongside a small pond of opaque water that has formed from

the mist sprayed by the overhead hoses.

“Gently, gently,” Matthews coaxes, as the trio presses a board-and-foam support to the plank to ease it from the muck. “If this wood slips into the water, I won’t be the one to fish it out, I can promise you that!” Fortunately, they’ve all had ample practice

in this sort of maneuver and shift the plank without incident to

a nearby table for cataloguing.

Later, seated on wooden steps descending from the shed entrance down to the boat, Matthews, who has been toiling over ships at Yenikapi for the past three years, reflects on why the finds here are so revealing.

|

| A ceramic shard’s two-tone glaze remains almost entirely intact. Aegean plates, Balkan oil lamps, North African amphorae; glass, metal, ivory and leather—all evoke a widespread, long-lived mercantile empire centered on Constantinople. |

“It’s the amazing details,” she observes. “Just from examining the tool marks, we can tell if the planks were fitted first—the style of boatbuilding used in the seventh century—or if the frame came first, then the planks, a technique that didn’t become wide-spread until around the ninth century.” If the planks are joined by wooden tabs called tenons slotted into mortise notches, the ship was constructed around the seventh century, Matthews explains. If they’re joined by wooden dowels, it was built after the ninth century. “Exotic stuff, no?” she says with a smile and a shrug. “It’s what we nautical archeologists live for.”

Even seemingly insignificant minutiae give clues to the extraordinary sophistication of Byzantine shipwrights. Analyzing the dowels used

on different categories of

vessels, archeobotanist Nili Liphschitz from Tel Aviv University determined that the pegs connecting planks on the cargo ships were hewn from the trunks of trees, whose rigidity kept the hulls from bending. She ascertained that similar dowels

on lighter galleys were

made from more supple tree branches to impart the flexibility needed to prevent the longer boats from snapping in two.

According to Matthews, such principles of ship design were handed down from father to son or from master to apprentice. “You didn’t find the design written down anywhere,” she explains. “You just built with what you recalled.”

As ships are dug up, the painstaking process of documentation and conservation begins. First, each one is meticulously photographed in close-ups which are then arranged in a computer photomontage of 100 to 150 images to depict the boat in its entirety. By zooming in on the photomontage, researchers can even detect cuts left in the wood from the various tools used to build the ship.

Next, a three-dimensional computer model of each ship is created using a laser-like instrument called “total station” to map its contours. Essentially, the device records as many as 10,000 separate points on the boat’s surface and connects the dots to replicate its shape. This technological marvel is so accurate “it can copy the head of ant,” quips Matthews.

|

|

Top: Among the finds have been baskets of 1200-year-old fruit seeds, olives and even cherries nestled next to the ship’s captain’s ceramic kitchen utensils.

Above: This delicately-fashioned sole of a wooden shoe bears a Greek inscription on the instep that roughly translates: “Wear this shoe in health, lady, and step into your happiness.” |

Once the computerized representation is complete, archeologists trace the vessel in detail on large sheets of clear plastic acetate,

dismantle it piece by piece, make

further acetate drawings and write exhaustive descriptions of the separate elements, then transport the planks to holding pools.

Because the fragile cell walls of the wood are supported by water, the ship timbers cannot be allowed to dry out. Instead, they are immersed in stainless steel tanks of polyethylene glycol (peg), a wax-like ingredient used in such products as skin creams, lubricants, toothpaste and eye drops. Over a period of 18 months to two years (for soft tree species like pine) or up to three years for harder varieties such

as oak and chestnut, the water inside the cell walls is replaced

by peg, which solidifies and stabilizes the wood.

Once the pieces are preserved with peg, archeologists re-

assemble them to study how the boat is put together, then disassemble everything for storage. Eventually, some of the planks, frames and entire re-assembled ships will be displayed in a

museum while preservation continues on other pieces. It’s an

on-going process that is likely to take decades, says Matthews.

“There’s a rule of thumb for underwater archeology,” she opines drily. “For every day of excavation, count on months in

the laboratory.”

But instead of waiting years to put the ships on display, she suggests, why not turn the laboratory into a living museum? “You could have big rooms with glass windows and people could watch the researchers at work, examine the design plans on the walls and witness the boats taking shape,” Matthews enthuses. “It would be fabulous.”

Wouldn’t the archeologists get distracted, I ask.

“You get used to it,” she replies. “Our lab at Bodrum [on Turkey’s Aegean coast] was outside and people would talk to us all the time. Here, visitors wouldn’t get in the way if they were behind glass windows.” Such open labs exist at the Portsmouth (uk) museum dedicated to the 16th-century Tudor warship Mary Rose, she adds, so why not here in Istanbul?

So far, local authorities have not decided what ships and artifacts will be in the museum or even where the museum will be

located. One proposal is to incorporate some of the nautical relics into exhibition spaces inside the train and metro station complex.

|

| Among the “millions” of ceramic sherds recovered, says Gökçay, not all are worth cataloging and conserving. Although digging will end in 2010, conservation and study will continue for years afterward. |

Kocabaş would prefer the main museum to be situated directly on the water, like the Vasa Museum in Stockholm, Roskilde’s Viking ships and others. “People could see the wrecks in a proper nautical context, rather than a kilometer away from the sea, as

at Yenikapi,” he points out. The ideal location, he proposes, would be on the site of the former shipyards along the Golden Horn, closer to the historic district and thus likely to attract more visitors.

But first, Kocabaş, Gökçay, Matthews, other archeologists,

researchers, engineers and work crews have at least two more winters to contend with before the monster dig winds down.

“Most of the time I’m glad not to have a desk job,” Matthews muses as we emerge from the cool shed into the late afternoon sunlight. “But in the winter here, standing in the mud, as the ice-cold water starts rising and your feet and fingers start freezing, snow flies through a hole in the plastic sheeting and you struggle to hold onto your pencil to record readings from the ‘total station’ mapping, the one thing that pops into my masochist’s mind is that I actually chose this job.”

And is it all worth it, I ask.

“Oh, yes,” she replies, without a moment’s hesitation.

|

Richard Covington (richardpcovington@gmail.com) writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, the International Herald Tribune, the Sunday Times and other publications from Paris. He is also a contributor to What Matters, a book of 18 essays and photojournalism on environmental, health and social issues (Sterling/Barnes & Noble, 2008). |

|

Lynsey Addario (www.lynseyaddario.com) is a freelance photojournalist based in Istanbul. This year she was awarded the Getty Images Grant for Editorial Photography for her continuing work in Darfur, Sudan. |