t a simple medical clinic in Lesotho last November, Wafaa El-Sadr saw the fruits of nearly three decades of unstinting toil. Row upon row of colorfully clad women, pregnant or with babies in their arms, sat waiting for HIV treatment at the one-story Qoaling Filter Clinic in Maseru, the capital of this land-locked, mountain-ringed southern African country. A few years ago, these women could expect little or no treatment for the disease, which infects one quarter of Lesotho’s population. Today, the majority of them receive comprehensive care for themselves and their children: a full range of antiretroviral drugs, testing for mothers and infants, and long-term follow-up and counseling. “It is the most beautiful complete model you could imagine,” El-Sadr says.

t a simple medical clinic in Lesotho last November, Wafaa El-Sadr saw the fruits of nearly three decades of unstinting toil. Row upon row of colorfully clad women, pregnant or with babies in their arms, sat waiting for HIV treatment at the one-story Qoaling Filter Clinic in Maseru, the capital of this land-locked, mountain-ringed southern African country. A few years ago, these women could expect little or no treatment for the disease, which infects one quarter of Lesotho’s population. Today, the majority of them receive comprehensive care for themselves and their children: a full range of antiretroviral drugs, testing for mothers and infants, and long-term follow-up and counseling. “It is the most beautiful complete model you could imagine,” El-Sadr says.

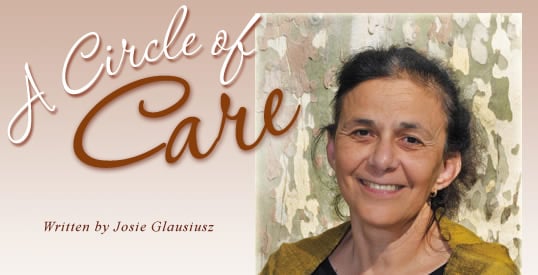

That this miracle exists is largely thanks to El-Sadr, the director of the International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs (ICAP), which supports the Maseru clinic as well as 26 others in Lesotho and some 400 more in 14 other countries across Africa. Born in Egypt in 1950, El-Sadr is a physician of unusual zeal and passion who has been treating people with HIV and AIDS since the earliest days of the epidemic in the 1980’s. She is now chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Harlem Hospital in New York, professor of clinical medicine and epidemiology at Columbia University and, most recently, recipient of a 2008 MacArthur Fellowship “genius award.” Her impressive resumé belies a disarming modesty: At times it seems she credits every achievement to her colleagues, community workers and patients. “She really is enormously accomplished on a rather grand scale,” says her collaborator Elaine Abrams, a professor of pediatrics at Columbia who works with El-Sadr on programs to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. “She totally understates her gifts and her brilliance. She is always more than willing to share responsibility for the good or the accomplishments.”

Of the care provided by the Lesotho clinic—a place she describes as “buzzing, full of life and energy”—El-Sadr says simply that it is “impeccable.” A staff of two nurses tends patients in an old building without fancy equipment, yet the all-encompassing care they provide—based on a community model developed by El-Sadr in Harlem and adapted to Africa by ICAP—is a radical improvement on the past. Characteristically, she insists that accolades be directed to the local staff and medics. “It’s their work,” she says. “We just helped them to make it happen.”

raped in her own colorful shawl, her jet-black hair framing a kindly face and warm brown eyes, Wafaa El-Sadr betrays barely a hint of the inner force that drove her to implement such sweeping change. She was born into a family of physicians: Both her parents were doctors, and they imbued her with an ethos of public service. “I grew up in an environment of thinking that your career had to have some meaning,” she says, her conversation punctuated by the rat-a-tat-tat of drilling from the construction site beneath her compact, spartan office at Harlem Hospital in New York City. For women in Egypt, she explains, the medical professions were not unusual choices, and more than half of El-Sadr’s class at Cairo University was female. “People here think that women are oppressed and deprived of education” in her home country, she says, and they are often surprised to learn that women have practiced medicine in Egypt for generations.

raped in her own colorful shawl, her jet-black hair framing a kindly face and warm brown eyes, Wafaa El-Sadr betrays barely a hint of the inner force that drove her to implement such sweeping change. She was born into a family of physicians: Both her parents were doctors, and they imbued her with an ethos of public service. “I grew up in an environment of thinking that your career had to have some meaning,” she says, her conversation punctuated by the rat-a-tat-tat of drilling from the construction site beneath her compact, spartan office at Harlem Hospital in New York City. For women in Egypt, she explains, the medical professions were not unusual choices, and more than half of El-Sadr’s class at Cairo University was female. “People here think that women are oppressed and deprived of education” in her home country, she says, and they are often surprised to learn that women have practiced medicine in Egypt for generations.

It was El-Sadr’s turn to be astonished in 1976 when she arrived in the United States and learned how women in this country had, in earlier decades, struggled to enter medical school. As a newly minted doctor, she came to New York to study infectious diseases, believing that later she would return to Egypt. Her plans changed in 1981, when AIDS began its cruel advance on the population of her adopted city. “It was a scary, intense, incredibly fulfilling time, even though we didn’t know what caused AIDS and lots of people were dying,” she recalls. Fulfilling because “part of the biggest joy for me as a physician is the interaction with the patient. Because of how profoundly HIV affected people’s lives, because of its isolating nature, the tragedies and the triumphs, it motivates a very special and deep connection with patients.”

Perhaps because of this connection, El-Sadr realized early in the epidemic that existing care was often not well-tuned to her patients’ needs. Many of them came from ruptured families, or families with more than one infected member—a spouse or a child. Some also were infected with tuberculosis (TB); others were drug-addicted. All had to deal with the social stigma branding people with HIV and AIDS. “When we looked at people affected by HIV and TB in the community here in Harlem, they were largely very poor, largely disenfranchised economically and socially. They had very weak social-support networks, and they were often alone,” El-Sadr explains. “It crystallized in my own mind the importance of thinking about not just the person with HIV or TB but the context in which they existed: the societal context, the community context, as well as the family context.”

Out of this realization arose El-Sadr’s standard of care: Holistic, multidisciplinary, family-focused, it addressed not just patients’ medical needs, but also their economic and psychosocial needs. She formed teams of health care workers—including a doctor, nurse, nutritionist and social worker—who offered patients and their families psychotherapy and nutrition counseling, as well as assistance in finding housing, financial benefits, soup kitchens and drug treatment. Patients would be “enveloped in this team.”

t is this model that ICAP, based at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, has introduced across sub-Saharan Africa. Since 2004, ICAP’s community-based treatments have transformed hundreds of clinics that serve people not so different from those in Harlem: poor, disenfranchised and stigmatized. Thanks to PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief, launched by US President George W. Bush in 2003), which largely funds ICAP, the organization now can provide services that were unimaginable five years ago. According to Abrams, more than half a million HIV-positive people in Africa now receive care with aid from ICAP.

t is this model that ICAP, based at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, has introduced across sub-Saharan Africa. Since 2004, ICAP’s community-based treatments have transformed hundreds of clinics that serve people not so different from those in Harlem: poor, disenfranchised and stigmatized. Thanks to PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief, launched by US President George W. Bush in 2003), which largely funds ICAP, the organization now can provide services that were unimaginable five years ago. According to Abrams, more than half a million HIV-positive people in Africa now receive care with aid from ICAP.

Like Lesotho, Tanzania, too, is a “remarkable” success story, says ICAP country director Amy Cunningham. In 2003, fewer than 500 people in Tanzania were being treated for HIV. Today, ICAP supports or provides care for 40,000 people at 220 sites—hospitals, clinics or dispensaries—using the community-based model devised by El-Sadr. In addition to direct financial aid, Cunningham explains, ICAP provides training, on-site mentoring, financial management, counseling and testing to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV as well as lab equipment, solar panels, water supplies and even new buildings.

One other innovation El-Sadr introduced in Harlem that ICAP applies widely is the training of people with HIV to become peer educators in their communities. It’s all part of her commitment to empowering the people who live at the heart of the epidemic: Indeed, of 700 staff employed by ICAP in the US and Africa, most are African. Among them are Bola Oyeledun, who directs the ICAP-Nigeria program. Nigeria, she says, is a country with more than three million people infected with HIV, and health care is often rudimentary. At first, ICAP teams often had to help clinics install lights, electricity and even water. Oyeledun found herself asking, “Can I really do this?” But for El-Sadr, nothing seemed insurmountable. She told Oyeledun, “Yes, you can, you can really do it. We’re here to support you,” the Nigerian doctor recalls. “She believed in my ability to get it done, and that gave me the confidence to build the program.”

|

| ICAP |

|

“Wafaa,” Oyeledun adds, “really loves what she’s doing. She doesn’t see numbers. She sees people, each person, each individual, each child.” Which could explain why, despite her exalted status, El-Sadr still sees her own patients once a week back in Harlem. These days, thanks to antiretroviral drugs that keep HIV in check, their medical problems are much more likely to be the sort of illnesses that afflict people who don’t have HIV. (“I tell my patients, ‘We’re growing old together,’” El-Sadr says.) She also continues to conduct her own research: Most prominently, she was a lead investigator in the 2006 SMART trial, which found that breaks from antiretroviral treatments significantly increased the risks of opportunistic infections and death among HIV-infected patients.

She also travels often to Africa, sometimes as frequently as twice a month. It’s where she claims she finds her ideas, by listening. “What’s stunning to me is how creative the teams are,” she says. “That’s why I love to visit. I go, they’ve identified an issue, they’ve worked together on a solution, and it’s remarkably creative and it’s different from country to country. I love to give them the space to do that.” Her unwavering instinct to credit others could explain why she maintains her low-key demeanor in spite of her newfound renown as a MacArthur winner. Recently, says Cunningham, “We were over at her house for a country director meeting. And Wafaa’s in the kitchen scrubbing up the dishes. We said, ‘Wafaa, you just won a genius award—sit down!’ She said, ‘No, no, I just want to get it all sorted out.’”

As for how she intends to spend the half-million-dollar, “no-strings-attached” award—which came “completely out the blue”—El-Sadr says she doesn’t know yet. Whatever it is, it’s likely to be innovative. “I love being part of something creative and new and evolving,” she says. Or, as Elaine Abrams puts it, “I always saw the MacArthur as this acknowledgment of individuals who had the courage to think outside the box, to think about good things for the world,” she says. “This is not just academic with Dr. El-Sadr. It is about making the world a better place.”

|

Josie Glausiusz (josiegz@earthlink.net) is a journalist and editor specializing in science. Her articles have appeared in Nature, Wired, Discover, The Wall Street Journal, Scientific American Mind, and OnEarth. She is the co-author, with photographer Volker Steger, of Buzz: The Intimate Bond Between Humans and Insects (Chronicle, 2004). She lives in New York City. |