ur quarry emerges from beneath an overhanging rock, its pale coat camouflaging it against the dusty background on Jabal Samhan, a rugged mountain range rising to 2100 meters (6990') in southern Oman. Positioning itself in front of a vertical rock face, the leopard lifts its tail stiffly and sprays the rock with a pungent calling card. Then it sniffs the boulders for evidence of other visitors and slinks off down the trail, leaving us awestruck by its casual majesty.

ur quarry emerges from beneath an overhanging rock, its pale coat camouflaging it against the dusty background on Jabal Samhan, a rugged mountain range rising to 2100 meters (6990') in southern Oman. Positioning itself in front of a vertical rock face, the leopard lifts its tail stiffly and sprays the rock with a pungent calling card. Then it sniffs the boulders for evidence of other visitors and slinks off down the trail, leaving us awestruck by its casual majesty.

|

| ANDREW SPALTON |

| More than a dozen remote cameras in Oman’s mountainous Dhofar region captured several hundred photos of the critically endangered Arabian leopard. Researchers were surprised that leopards often tripped the cameras during daylight hours. |

It’s hard to absorb the significance of what we’ve just witnessed, and perhaps even harder to picture the Arabia of ancient times when sights like this were commonplace. Big wild animals were once plentiful here and encounters with them weren’t so welcome. “The pasturage ... supports flocks and herds of all sorts...,” wrote the Greek geographer and historian Agatharchides in the second century BC. “Crowds of lions, wolves and leopards gather from the desert, [and] against these the herdsmen are compelled to fight day and night in defense of their flocks.”

These days, things are different. Travelers to Arabia have more reason to marvel at the cities than the wildlife, and more reason to fear cars than carnivores. It’s hard to imagine that animals we associate with the African savannah might coexist with so much man-made progress—and sadly, for the most part, they don’t: The lions disappeared many centuries ago; the wolves are now few in number. But somehow, largely forgotten by the human population with whom it shares this unfor-giving landscape, the leopard has managed to linger. Jabal Samhan, a hyper-arid net-work of rocky plateaus and nearly impenetrable gullies, a place where June shade temperatures regularly top 46 degrees Centigrade (115°F), is one of the last lairs of the elusive Arabian leopard.

Arabian Leopard Factfile

Scientific name: Panthera pardus nimr

Head and Body Length: 1.3 meters (4' 4")

Weight: Male 30 kilograms (66 lbs), female 20 kilograms (44 lbs)

Habitat: Mountainous areas with forest/scrub, preferably with permanent water sources

Prey: Gazelle, ibex, hyrax

Threats: Persecution, poaching, habitat loss, prey depletion

Behavior: Generally thought to be nocturnal, but this is now in question. Marks territory using scrapes, scent marking and defecation.

Unlike Agatharchides, however, I still haven’t seen an Arabian leopard in the wild. Very few people have. After all, this is one of the rarest animals on the planet, classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as “critically endangered,” meaning that it faces an extremely high risk of extinction. Though once it roamed the mountains of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen, as well as Oman, this feline phantom has now all but vanished. The individual we monitored this morning was an image on our video screen, captured in a remote-filming operation designed to help save what could be the last viable population of Arabian leopards, deep in the south of Oman.

For many years it wasn’t clear whether the leopard still existed in the mountains of Dhofar. There are few visitors to this difficult terrain. Nomadic herdsmen occasionally pass through with livestock, and frank-incense harvesters pay brief visits in the spring and fall. But few linger. And even if they did, the odds of a chance encounter with an animal wary of man and supremely well adapted to its environment are next to nil. The only tangible evidence of the leopard’s continued survival was the occasional goat seized from a settlement on the edge of the territory, often followed by the discovery of a leopard carcass bearing a lethal gunshot wound.

The leopard has enjoyed formal protection in Oman since 1976. In 1997, further safeguards were introduced when an area of 4500 square kilometers (1740 sq mi) comprising Jabal Samhan was declared a protected area. But was it too late? Had the leopard already edged too far toward extinction? It wasn’t clear—until one man took up the challenge to photograph the cats.

The leopard has enjoyed formal protection in Oman since 1976. In 1997, further safeguards were introduced when an area of 4500 square kilometers (1740 sq mi) comprising Jabal Samhan was declared a protected area. But was it too late? Had the leopard already edged too far toward extinction? It wasn’t clear—until one man took up the challenge to photograph the cats.

“It started in 1989,” explains resident wildlife cameraman David Willis. “I was interested in filming ibex and heard that in Jabal Samhan you could see herds of up to 40 animals. One night while camping we heard a leopard calling. I’d heard them before in Africa but didn’t think it was possible to encounter them in Oman. Then, over the next few days, we saw the tracks.”

Willis decided to try to photograph the animals using a homemade system of re-mote 35-mm cameras, installed in locations where he had found signs of leopards, such as footprints and “scrapes” made by pawing the ground. Each camera was linked to a carefully disguised pressure plate—a ply-wood platform which would trigger the shutter when it was stepped on. He left the setup in the mountains and went back to his home in Oman’s capital, Muscat, some 1000 kilometers (620 mi) away.

|

| HADI AL HIKMANI |

| Pre-monsoon winds off the Arabian Sea brush clouds across the tops of the hills in the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, where leopards have enjoyed official protection since 1976. Rugged terrain and fierce summer temperatures keep human visitors to the region few. |

“It was an experiment,” he explains as we leaf through his collection of big-cat mug shots. “When I recovered the film three months later and saw that 15 frames had been shot, I assumed they would be pictures of dogs and don-keys—maybe the occasional camel.” It was only when Willis had the film developed in Muscat that the success of his experiment became clear. There, among the dogs and donkeys, were eight pictures of an animal few had ever seen in the wild: likely the first-ever images of the Arabian leopard.

Studying the images he places in front of me, there’s no denying that the Arabian leopard is a magnificent beast. Once, three subspecies of Arabian leopard prowled this peninsula. Now only one remains: Panthera pardus nimr. Its coat is a creamy-buttermilk color, its rosettes (the technical name for the spots that pepper its lean frame) a dark inky black, rendering it virtually invisible in its rocky hideout. Although smaller than its African counterpart, this is a powerful predator—though clearly not one averse to a little fun: One series of shots shows a leopard in a variety of airborne poses, returning repeatedly to bounce on the spring-loaded pressure plate. In the face of such joy for life, I find it easy to sympathize with Willis’s broader focus: to save the leopard from demise in the wild.

Luckily, I’m not the only one convinced of that necessity. In 1995, Dr. Andrew Spalton, adviser for Conservation of the Environment to Oman’s Diwan of Royal Court—the sultan’s cabinet—heard about Willis’s work and immediately recognized its potential. Soon after that, Oman’s Arabian Leopard Survey was born.

Research Methods

Researchers on Oman’s Arabian Leopard Survey employ a variety of techniques to learn more about their subject.

Ground surveys: Researchers comb the area for signs of leopard presence: territorial scrapes, scats or urine, scent sprays and evidence of kills.

Camera trapping: A weatherproofed camera is sited next to routes known to be used by leopards. The camera may be triggered either by a pressure plate or an infrared beam. Researchers can use the resulting images to identify individual leopards.

Satellite tagging: Leopards are trapped, sedated and fitted with collars carrying satellite tags. Although expensive, the collars can provide detailed information about the leopards’ movements and behavior.

Studying rare wild animals is difficult at the best of times, but tracking the Arabian leopard is a monumental task. It was clear that studying the animals by direct observation was not an option; even setting and maintaining camera traps turned out to be a lesson in patience and perseverance. The first problem was getting to the survey site. Jabal Samhan has no roads and few sources of fresh water. An expedition into the interior starts by boat from a port on the Indian Ocean such as Salalah, and then requires several days of hiking with supplies and technical gear. Finding anything here—even finding the same spot twice—is difficult enough. Finding a feline version of the Scarlet Pimpernel is not a task for the easily frustrated.

“We suffered endless technical issues,” explains Spalton. “Our equipment overheated, leopards scent-marked the cameras by rubbing against them, donkeys knocked them over, mice chewed through the cables.” Even when the camera-traps worked, the results were less than reliable. “Having mounted a major expedition to recover films and reset traps, we could get entire films full of nothing but donkeys. From a total of 13 cameras, we might get one leopard image,” he says. Nonetheless, the patience of Spalton and Willis and their small team eventually paid off. Between 1997 and 2000, a total of 251 photos of Arabian leopards were obtained, and the scientific analysis could begin.

It is actually scientifically true that leopards never change their spots. The shape and pattern of rosettes on each leopard’s coat are unique, rather like a human finger-print. Analysis of the camera-trap images revealed 17 individuals: 16 adults (nine females, five males and two of unknown sex) and, most exciting, a cub. The results suggested a total population of around 50, confirmed that they were breeding and offered invaluable information about leopard behavior.

Leopards are widely considered nocturnal animals. However, in one of the three monitoring areas, the leopards were most active from six to nine in the morning and three to seven in the evening, with some 70 percent of their activity in daylight hours. “This could be due to the different environmental conditions in this area,” offers Spalton. “It includes a steep-sided gorge with permanent water and plenty of shade. For much of the day, the leopards don’t have to deal with high temperatures and water loss.” But a more important factor, he suggests, is the absence of human activity here. Leopards will avoid humans, at least during daylight, but with humans absent the leopard can adjust its activities to suit environmental conditions.

|

|

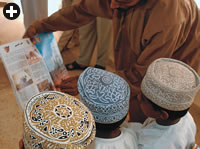

| TOP: KHALID AL HIKMANI; LOWER: ANDREW SPALTON |

| Top: Using goats as bait, researchers in 2001 trapped four leopards and fitted them with satellite tagging collars. This allowed real-time tracking of their movements: One leopard covered 476 kilometers (295 mi) in 55 days. Above: A Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve ranger talks to local residents in an effort to persuade them that the economic benefits of leopard preservation can outweigh the risks of livestock predation. |

The camera-traps recorded vital information about some of the leopard’s habits, but could only provide snapshots from which behavior could be surmised. In 2001, Spalton led the team on an even more ambitious project to gather data on the behavior and range of individual animals by capturing leopards and tracking them using satellite collars. It was a military operation, requiring plenty of equipment.

“We had lots of help from the Royal Flight and the Royal Air Force of Oman,” says Spalton. “They used helicopters to fly us in and left us there for 60 days. We used cage-like traps baited with goats, withdrew several kilometers and waited, monitoring the traps with high-frequency radios.” It was an exciting field trip. Camping out in the jabal area, the researchers encountered a number of its other inhabitants: striped hyenas (Hyaena hyaena), Arabian wolves (Canis lupus arabs) and Verreaux’s eagles (Aquila verreauxi). But would they find any leopards?

“We had a couple of false alarms,” Spalton recalls. “A signal on the radio meant the trap had been triggered. We would rush over to see what we had caught and find a partridge or a wolf. Then one morning, about 10 days into the trip, we raced over in response to a signal and found two leopards—one in the trap and one outside. It was a breathtaking sight.” Here, finally, in the flesh, was the creature Spalton and Willis had spent so much time pursuing—and it was about to share some of its secrets.

Satellite tagging is one of the most powerful tools available to wildlife researchers. Animals are captured, sedated and fitted with collars carrying small gps devices. The collars used by Spalton’s team store data for three months and then drop off. Despite some technical hitches, four collars have now been recovered and the data theytained reveal some astonishing information about the leopards’ movements, for some travel long distances. Indeed, one covered 476 kilometers (295 mi) in a 55-day period.

|

| ANDREW SPALTON |

| Four years of treks to set up and recover the remote cameras resulted in more than 200 images of leopards—and many more of donkeys, dogs and camels. |

That is some trek by any standards, but here such distances are not difficult to explain. Though it is an apex, or top-of-the-food-chain, predator, the game available to the Arabian leopard is very sparse. The energy in every ecosystem starts with the primary producers, the green plants—and the few dusty specimens that survive the hyper-arid conditions of Jabal Samhan can only support a sparse population of the herbivores that leopards eat. To survive and breed, the leopards need to patrol a vast territory to find their prey. In fact, data gathered by the survey team suggest that male leopards in Jabal Samhan have an average annual home range of 180 square kilometers (70 sq mi), while leopards living in lush grasslands, which support a higher concentration of prey, may have a range of only 50 square kilometers (19 sq mi) or even less.

Close Cousins: Other Leopard Subspecies Around the World

Leopards are among the most adaptable animals in the world. They occur in habitats ranging from the jungles of Southeast Asia to the high, cold mountains of the Himalayas and from the deserts of Arabia to the bush of Africa. The Arabian leopard is one of nine subspecies of leopard (Panthera pardus):

Indo-Chinese leopard (P. pardus delacouri) in mainland Southeast Asia

Indian Leopard (P. pardus fusca) in India, southeastern Nepal and northern Bangladesh

North Chinese leopard (P. pardus japonensis) in China

Sri Lankan leopard (P. pardus kotiya) in Sri Lanka

Javan leopard (P. pardus mela) in Java

Amur leopard (P. pardus orientalis) in the Russian Far East, northern China and the Korean Peninsula

African leopard (P. pardus pardus) in Africa

Persian/Iranian leopard (P. pardus saxicolor) in Southwest Asia

Arabian leopard (P. pardus nimr) in the Arabian Peninsula.

The need for a large territory has forced the leopard to adapt its behavior in other ways. Much of the jabal is accessible only by well-defined pathways. This forces leopards to share territory, which is very unusual for such solitary creatures. It is thought that leopards manage this by leaving signals to warn others from occupying the same area at the same time—urine spraying, feces deposition, cheek rubbing and making scrapes. These techniques may also help males and females find each other to breed.

The leopard’s need for food, and its large range, has also brought it into conflict with another apex predator: humans. The relationship between the Arabian leopard and the human population with which it shares its territory is complex. Hadi al Hikmani became involved with the Arabian Leopard Survey as a guide, providing camels for some of the expeditions mounted by Spalton and Willis. He comes from a jabali family—nomadic tribesmen who keep camels in these hills, bringing them down to lower pastures when the khareef, the southwest monsoon, brings rains. “In some ways my parents regarded the leopard as an enemy to be feared, as it kills livestock,” says al Hikmani. “But if we heard the leopard calling when we sat round our camp at night, everyone would get very excited. It was regarded as a good omen. The older men said it would be a good year ahead.”

These days, al Hikmani is employed full-time by the project and helps bridge the gap between the local population, many of whom still view the leopard merely as a livestock killer, and the Omani government, which seeks to protect an endangered predator. “The main conclusion of our scientific work is that there is a breeding population of leopards here in Oman and that it’s potentially viable,” says Spalton. “This probably represents the last opportunity to conserve the Arabian leopard in the wild. We established the Arabian Leopard Survey to find out more about the leopard, but given what we now know, we want to use ongoing funding to address real conservation methods. This is where the real work starts: There are many more challenges ahead.”

|

| David Willis |

One of the biggest issues facing the Arabian leopard in Oman is persecution by the local population in response to live-stock losses. Spalton is keen to demonstrate that preserving the leopard can bring economic benefits, partly through the introduction of carefully controlled, low-impact tourism projects. However, as old conflicts are resolved, new ones are created. As the satellite-collar data indicate, the leopards need huge territories in order to survive. Yet development creeps ever closer in the form of new roads, houses and hotels. Once, the survey team caught and tracked leopards outside the Jabal Sam-han Nature Reserve in mountainous areas near Yemen—possibly part of a separate population that ranges across the border. However, they have already noticed a decline in the number of animals that have their pictures taken on camera-traps in this area.

|

| ANDREW SPALTON |

| Local schools, too, are teaching that leopards are not just large pests, but integral to the southern Omani ecology. |

So what does the future hold for the shadowy leopard of Oman’s Jabal Samhan? I ask Spalton how the sultanate will shoulder the responsibility of protecting what may be the last sustainable group of wild Arabian leopards. “We have to keep the leopard on the public radar,” he replies. “It’s all about people.” And this is where al Hikmani again has a role to play, for the Diwan of Royal Court recently commissioned David Willis to make a film about the Arabian leopard, following al Hikmani and his work, in the hope that this flag-ship species will become a source of pride for Omanis and its plight an issue of national concern.

“To keep its place in the mountains, the leopard needs to find a place in people’s hearts and minds,” Spalton says. Having adapted its habits to survive the 2200 years since it was witnessed by Agathar-chides, the leopard may be able to succeed in making this further critical last leap. If it can’t, the only place the next generation will see this mysterious mammal is on film.

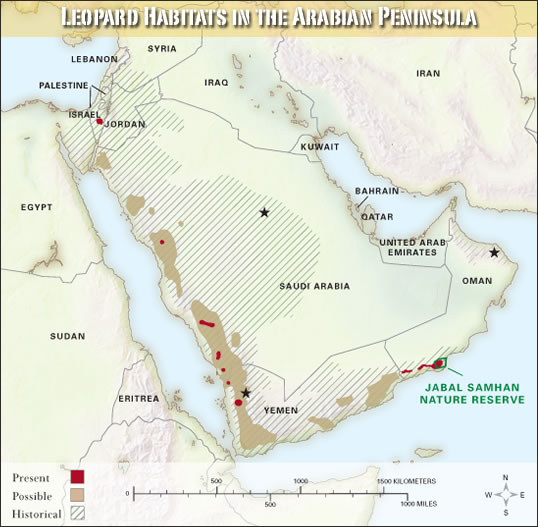

P. pardus nimr: Distribution and Status

Formerly common throughout the Arabian Peninsula, the Arabian leopard now remains in only a few scattered populations.

Oman: Leopards were once present in the Musandam Peninsula and the Al Hajar Mountains in northern Oman and in the Dhofari Mountains in the south. They are now thought to be extinct in the Al Hajar Mountains. A 2007 survey found some evidence of leopards in Musandam, but this population may comprise only a few animals. The Dhofar population could comprise 40 to 50 animals.

Saudi Arabia: Small, isolated populations are thought to exist in remote parts of the Hijaz and the Sarawat Mountains in the west. There have been no confirmed sightings since 2002.

United Arab Emirates: Leopards may once have used the UAE as a corridor between Musandam and the Al Hajar Mountains. There is evidence of leopard killings by locals during the 1990’s and in 2001, but no data has been acquired since. Experts have estimated the population in the northern Emirates and Musandam to be as few as five to 10.

Yemen: The presence of leopards was recently confirmed in the northern part of the western highlands. They have also been recorded in the central part of the western highlands, in the southwest and south, and in the east close to the Oman border, but their status is little known. They face severe persecution in wild, and it is suspected that many animals have been poached for private collections.

Jordan: The last confirmed sighting was in 1987. Recent field surveys have been unable to confirm subsequent reports.

Israel: Recent survey work using dna extracted from feces confirms the existence of small numbers of Arabian leopards in the Judean Desert and Negev highlands.

Find out more:

To find out more about the Oman Arabian Leopard Survey, visit www.oryxoman.com/leopard_main.html. Volunteer researchers are being recruited through Biosphere Expeditions for field work associated with the Arabian Leopard Survey in Musandam. See www.biosphere-expeditions.org for details.

|

Freelance nature correspondent Anna McKibbin (anna@digital-diaspora.com) is fascinated by the wildlife of the Middle East. “Its wilderness guards secrets we haven’t yet begun to understand,” she says. This is her second article for Saudi Aramco World. She lives in England. |