| Chinese–Islamic decorated implements for the burning of incense often included a covered burner, a box to hold unburned incense, a vase and a spatula. Such a set would occasionally also include a pair of metal chopsticks for handling burning incense. |

|

|

Above: Arabic calligraphy is shaped into the popular Chinese character for “longevity.”

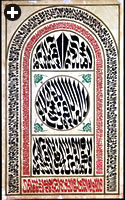

Above right: Verses from the Qur’an are shown in the form of a mihrab, or prayer niche.

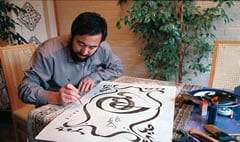

Below: “Arabic calligraphy in Chinese style is the crystal of collected wisdom from countless ancestors,” says Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang, shown here at work in his studio. |

|

n contrast, the appreciation of Chinese–Islamic works has been negligible. For collectors of traditional Chinese art, these works are not Chinese enough; for Islamic-art collectors, they seem too alien to be considered truly Islamic. Today, however, a world audience is awakening to one exceptional Chinese–Islamic art form—calligraphy.

n contrast, the appreciation of Chinese–Islamic works has been negligible. For collectors of traditional Chinese art, these works are not Chinese enough; for Islamic-art collectors, they seem too alien to be considered truly Islamic. Today, however, a world audience is awakening to one exceptional Chinese–Islamic art form—calligraphy.

The popularity of this calligraphy, called sini (“Chinese”) in Arabic, may have to do with the fact that it is extraordinarily vibrant, and that it has survived into the 21st century as a living medium. Indeed, contemporary Chinese calligraphers have acquired an international following, none more so than Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang.

Hajji Noor Deen, whose title means he has made the pilgrimage to Makkah, preserves the same techniques that have been used since paper was invented around 2000 years ago. With compositions that acknowledge the past, this neatly bearded 45-year-old has almost single-handedly brought contemporary Chinese–Islamic art to the world. In 2006, he was among the calligraphers featured at the British Museum’s Word into Art exhibition—called the most important exhibition of modern Islamic calligraphy. Appearing in a show subtitled “Artists of the Modern Middle East” was quite an accomplishment for an individual who was born and lives in China.

“Arabic calligraphy in Chinese style is the crystal of collected wisdom from countless ancestors. It is the Chinese Muslim’s resplendent treasure house,” says Hajji Noor Deen. And, he might well have added, there are many more treasures of this “collected wisdom” waiting to be recognized.

|

|

| The Zhengde emperor, who ruled from 1505 to 1521, was married to a Muslim, and is believed by some to have converted to Islam. Many ceramic objects from this time, like this incense-burner part, carry his regnal mark. |

Appreciating the scope of Chinese Muslim art is difficult, partly because there were few accounts or depictions of Muslim life in China until the 19th century, when Christian missionaries arrived in relatively large numbers. Photographs by American sociologist Sidney Gamble and the Rev. Claude L. Pickens, made in the 1920’s and 1930’s, provide more insights than the usually descriptive Ibn Battuta did. The great 14th-century traveler from Tangiers had remarkably little to say about the months he claims to have spent with Muslim hosts in China, and his account gives no impression of having seen any Islamic artworks, although he was impressed by the figural art of the non-Muslims there.

Ibn Battuta’s journey to China took place toward the end of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). When he arrived, the Muslims who had settled in this Mongol-ruled empire were commercially successful and treated with more respect than the native Han Chinese, perhaps because the Mongols viewed the Muslims as outsiders like themselves. They recruited Muslims to fill government positions and even to manage state-run porcelain plants, writes Gauvin A. Bailey in Tamerlane’s Tableware (1996, Mazda). These were Chinese-speaking Muslims—mostly descended from Arab and Persian merchants and soldiers, often intermarrying with the Han Chinese but preserving a separate identity—and Uighurs, a Turkic people living in the country’s northwest who had embraced Islam.

|

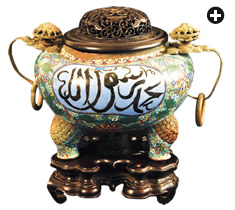

| This 18th-century cloisonné incense burner features the shahadah, or statement of faith, in Arabic, in two cartouches on opposite sides. |

A fundamental change for China’s Muslim communities came during the succeeding Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The Hongwu emperor, who reigned from 1368 to 1398, stripped them of their political and other advantages as the native Ming consolidated power. To reduce the Muslims’ importance further, he ordered them to marry Han Chinese and adopt Han customs, but since most of the offspring of these unions became Muslims, not Taoists, the community expanded rather than contracted.

The fortunes of Muslims in China had rebounded generally by the time of the Zhengde emperor (1505–1521). Much folklore surrounds this unpopular ruler, who was married to a Muslim and is believed by some to have converted to Islam. Although the tales of his dressing in Arab clothes and abstaining from pork are probably apocryphal, his reign was a prosperous time for Muslims in China and a productive time for art, with the imperial kilns producing quantities of Islamic ceramics.

|

| During the 17th and 18th centuries, porcelain rosewater sprinklers were a popular export item from China to Islamic lands. |

Contact between the Middle Kingdom and Muslims in the Middle East had existed for centuries before Ibn Battuta’s journey to China. As early as 651, only 19 years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, a mission led by his maternal uncle is thought to have visited an emperor of the Tang Dynasty. The traditional instruction of the Prophet, encouraging believers to “seek knowledge even as far as China,” suggests that this was about the most distant place that anyone could go in search of self-improvement. Distance was no impediment to the Muslim traders, who formed communities in the major seaports of Guangzhou (Canton) and Quanzhou, and later in Silk Roads oasis cities in the northwest. Despite occasional hostility, sometimes extending to massacres, the influence of Muslim settlers increased in coastal cities and throughout the empire.

The importance of Muslims in China between the seventh and the 14th centuries is not reflected in their artistic legacy, however. Rather than developing new art forms, they reused styles and imported easily transported objects from their original homelands, thus preserving their distinction from the Han. Apart from mosques and tombstones, in fact, there are almost no local artifacts from before the Ming Dynasty to show the existence of a sizeable Muslim population.

Then, toward the end of the 14th century, there was an esthetic awakening: Muslims began integrating Islamic concepts with Chinese artifacts, creating a hybrid that was more Chinese than anything else but featured elements from Muslim lands. They developed a new style of Arabic script and adapted objects used for traditional Taoist, Buddhist or Confucian practices to Islamic purposes. Veneration of God, rather than ancestors, began to be expressed in ways that have remained much the same until the 20th century.

|

|

| BRITISH MUSEUM / ART RESOURCE |

| This Ming Dynasty brush rest, produced in the southern province of Jiangxi, bears an Arabic inscription, but its shape refers to the “Five Great Mountains” of Taoism. |

The explanation for this flowering of a new culture lies in the way that many Muslims in China began to see themselves during the Ming era. During the Yuan Dynasty, they were part of an honored and distinct ethnic group known as semu and—at least officially—kept apart from the indigenous Chinese. Now they were no longer strangers in this land, and their increasing numbers were matched by a growing measure of Han Chinese blood. After Ming rulers replaced the Yuan, the semu became Hui: mostly Han Chinese by language and ethnicity, but Muslim by religion. Under the Ming, there was no longer any benefit to being an outsider. The Arab and Persian decorative arts that had previously been symbols of semu identity—reflected mainly in manuscripts and utilitarian ceramic and metalwork items like bowls and candlesticks—became increasingly irrelevant.

At the same time, the split between Muslim groupings in eastern and western China became more decisive. Regions with a heavy Central Asian influence, such as Xinjiang in the northwest, had been closely allied to the Mongol ruling class. The Turkic-speaking Muslims there had less in common with the Ming rulers than the Chinese-speaking Hui of eastern and central China. The latter grew closer to the imperial court and became influential patrons of the new art forms that developed during the Ming Dynasty. The art of the Turkic-speaking Muslims has retained a Central Asian feel to it. The uniqueness of Chinese–Islamic art is a Hui accomplishment.

Two main categories of Chinese art might be considered “Islamic”—wares made for Muslims outside China and those made for Chinese Muslims—and both reached their zenith during the Ming period. The highest-volume wares were intended for export to consumers in various parts of the Islamic world—mainly ceramics, China’s main export even before the Ming Dynasty. Although this trade was stopped at various times by imperial command, international demand for Chinese porcelain continued strong in markets as diverse as Sweden and East Africa. Muslims in India, Iran and the Ottoman Empire were avid consumers, sometimes going as far as having their names enameled on dishes and other ceramic commissions.

Wares made for Muslim patrons had to satisfy a variety of local requirements. For Middle Eastern destinations, where eating from a communal dish was de rigueur, Chinese kilns churned out extra-large sizes, more than 50 centimeters (20") across. Examples of these dishes, only a few of which survive in the Middle East, are in the Topkapı Palace Museum in Istanbul. Decorative styles also varied. The Ottoman court, for example, had a

passion for celadon, a porcelain known for its distinctive gray-green glaze. This was replaced in the 15th century by underglaze blue-and-white motifs such as bunches of grapes, later copied extensively by Ottoman ceramists.

On the other side of the Islamic world, Southeast Asia imported large dishes with religious inscriptions, as well as many small bowls decorated with “magic squares” and Arabic numerals. These consist of a grid usually composed of 16 small squares, each with a number (or sometimes a letter) inside. They were almost certainly meant for divination purposes, but exactly how they were used remains a mystery.

Rosewater sprinklers were among the most popular Chinese ceramics in the Islamic world. They looked like small flower vases with an elongated neck closed with a perforated silver top, and were usually made in underglaze blue-and-white or multicolored enamels. They rarely featured inscriptions or any other overtly Islamic decoration; rather, flowers were the most typical motif—appropriate for dispensers of rosewater. As with most of China’s ceramic exports to Muslim markets, figural imagery was rare. When they reached their destinations, such wares had a profound effect on ceramicists in different parts of the world. Ceramics specialist Oliver Watson, head curator of the new Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, writes that Chinese ceramics have been “the most important and consistent influence on Islamic pottery.”

|

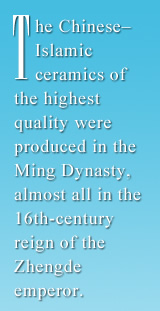

| In the majority of Qur’an copies from China, the text’s 30 sections are divided into separate volumes bound in leather or cloth. One volume could thus be read each day during the holy month of Ramadan. Below: A pen box from the 15th century is one of the few Ming Dynasty export items that was also widely used in China. |

Ceramics created for Muslims in China conformed to “Chinese taste” and had considerably less impact. This reflects the historical division between items made to imperial requirements, which became the model of decorum for the entire population, and those made for consumers outside the Middle Kingdom. Tastes changed often at the imperial court, ranging from the monochrome austerity favored by the Song Dynasty (960–1279) to the experimental flamboyance of the Qing (1644–1912). Imperial taste dictated the esthetics of the empire not only because of the rulers’ semi-divine status, but also because of the sheer quantity of items produced at their kilns. Regardless of what the prevailing fashion might have been at court, it was rarely the same as what foreigners required.

Chinese–Islamic ceramics of imperial quality invariably date to the Ming Dynasty, almost all from the reign of the Zhengde emperor. Hui influence at court enabled Muslims to commission porcelain of such superiority that huge prices are still paid for it today by collectors of imperial ceramics who are not deterred from their pursuit of pure Chinese heritage by the presence of Arabic or Persian inscriptions. These items are considered to be the pinnacle of Ming creativity. Decorative motifs include distinctive meandering arabesques of Islamic inspiration that appear on Zhengde porcelain of all types. They have the intense cobalt blue and the rich, tactile glaze that have made this dynasty’s ceramics the most collectible of all Chinese ceramics. The blue itself was mainly derived from Iranian cobalt that Chinese potters called hui-qing, or “Muslim blue.”

Islamic inscriptions on Ming porcelain are usually found on objects designed for the scholar’s table, such as brush rests, ink stones and water droppers. During the Ming Dynasty, a man’s highest calling was to be a person of scholarly or literary achievement, and this aspiration was reflected in the ceramics that were favored by prominent Chinese Muslims. They wanted to show their scholarly credentials in a conventional Han way by using the right implements, while making their religious affiliation clear by having some Islamic content. The same thing applied to jars, dishes and incense burners. These preserve traditional Chinese shapes with the addition of Arabic writing that might proclaim “God be praised for all His blessings” or “He who gets close to a perfume seller acquires a share of his scent.” Occasionally, the content is more personal: “O God! Protect Hui Ma Yun [from] the anger of the wicked,” reads the inscription on a jar in the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur—the only institution in the world to dedicate an entire gallery to Chinese–Islamic art.

|

| A pen box from the 15th century is one of the few Ming Dynasty export items that was also widely used in China. |

Sometimes the words are in Persian, serving less of a religious purpose than as a reminder of the Hui owner’s descent from Iranian soldiers or traders. These inscriptions might consist of elaborate Persian proverbs or, as in the case of a brush rest in the Percival David Collection in London, simply the Persian word for “pen rest.” Despite the existence of some Chinese ceramics with Persian inscriptions in such places as Ardebil, Iran, the majority of these wares were used by Chinese Muslims.

The Islamic content of inscribed ceramics does not always eclipse the traditional Taoist connotations that come with them. There are, for example, brush rests of a common type that features five stylized mountain peaks—an allusion to the “Five Great Mountains” of Taoism—but with Arabic or Persian inscriptions.

While Taoism and Buddhism are incompatible with Islam, Confucianism, the principal philosophy of China, is not. It has been linked to Islamic belief by Muslim scholars such as Wang Daiyu and Liu Zhi since the 17th century. The connection may seem strained, but the central message of a “Lord” (God) and a “Chief Servant” (the Prophet Muhammad) was comprehensible to Confucian adherents. Wang Daiyu explained the values of Islam in a typically Confucian manner: “If the country is not governed, it is because the family is not regulated. If the family is not regulated, it is because the body is not cultivated…” and so on until he shows how achieving personal perfection is the goal.

The Confucian elite’s preoccupation with the written word and with being “cultivated” worked well with the Hui. The Islamic world and traditional Chinese culture place calligraphy at the top of the art hierarchy. Not even a revolutionary as staunch as Mao Zedong could resist the lure of “reactionary” scholarly pursuits. His calligraphic works are among the least publicized but most respected of 20th-century China.

|

|

| This jar is notable both for its red underglaze decoration— blue was far more common —and for its four Arabic inscriptions, one of which contains a grammatical error. Although it carries the Zhengde emperor’s mark, it was probably made later, during the Qing Dynasty. |

The importance of calligraphy to Chinese–Islamic art is central: It is the only real difference between the creative output of Chinese Muslims and the rest of the population. Without its written inscriptions, porcelain made for the Hui would look like any Han ceramic. The same applies to the other major expressions of Hui esthetics: bronzes, cloisonné enamel and glass.

Glassware with Islamic inscriptions is less common than bronze or cloisonné work. It is mainly from the Qing Dynasty, not the Ming, and shares the same shapes and colors as the glass made at the imperial workshops in Beijing, but with the addition of Islamic invocations. Its purpose was to hold flowers, which in Taoist or Buddhist tradition can have ritual significance. For the Hui, they were simply vases.

Muslims do not use ancestral altars, which remain to this day the focal point of most Chinese traditional religious practice. Partly integrated into Han life, the Hui developed a modified system that would seem entirely out of place in other Muslim homes around the world. Rather than venerating ancestors at an altar, the Hui practice was to revere the Qur’an, which was placed on a table. Like Taoists, they burned large amounts of incense, but instead of being a process of communication with the spirit world, the intention was to cleanse and purify.

This activity did not have the same central role for the Hui as it does for ancestor worshipers, but the vessels they used for burning incense were based on those of the Tao. The traditional Chinese garniture comprised an incense burner flanked by two candlesticks and flower vases, while Muslims got by with an incense burner, an incense holder and a flower vase that might hold a spatula for stirring coal or ashes. There was also a decorative distinction: The Muslims’ censers were cast with appropriate Islamic inscriptions, usually in Arabic.

These brass or bronze vessels still exist in large numbers. There must once have been a massive quantity for so many to have survived the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s, when Muslims were persecuted for their beliefs and mosques were torn down. A large number of metal objects were also lost during the “Great Leap Forward” immediately before the Cultural Revolution, when they were collected as scrap and melted down as part of the communist state’s backyard industrialization plan.

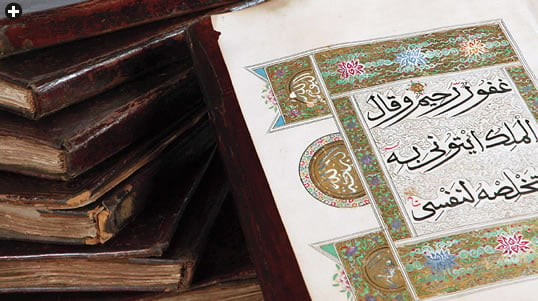

The extant incense burners are imposing in their solidity. Many bear reign marks of Ming emperors, just as porcelain objects do. As with ceramics, the marks are not necessarily accurate indicators of the era when the objects were made: During the Qing Dynasty, Muslims’ relations with their Manchu overlords were often poor; they became increasingly nostalgic for the golden age of the Ming and marked their ceramics correspondingly. The same reign marks can also be found on incense burners made of cloisonné, a technique closely associated with the Ming imperial court. Most of the censers that exist today are from the Qing era. While the bronzes with their bold Islamic inscriptions look stately in their monochromatic way, the cloisonné vessels are sometimes a little jarring. The delicate color scheme of blue with accents of red and yellow is not always improved by the presence of white or black cartouches on which Islamic inscriptions stand out vividly. Whether added to brass, bronze or cloisonné, the inscriptions usually incorporate blessings, the bismillah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”) or the shahadah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the Messenger of God”).

|

| Brass incense burners, such as this one from the 18th century, were lost by the thousands to the Cultural Revolution and the “Great Leap Forward.” |

Chinese Muslims also commissioned ceramic censers. Their shapes were usually based on metal prototypes, but the style of calligraphy they feature highlights an essential Chinese contribution to Islamic art. The Arabic and Persian writing on imperial wares of the Ming Dynasty is remarkable more for its presence than its esthetic properties; it tends to have been executed by artisans who, though competent, were uncertain of its meaning. On later ceramics, however, the calligraphy often exhibits an extraordinary vigor, unseen on ceramics from the Islamic heartlands, mainly because the calligraphers were not trying to create the angular look of a pen stroke. The Chinese calligraphic brush technique produces a result quite different from the reed pen used elsewhere in the Islamic world. It has a dynamism that is similar to dance and a spontaneity that is more energetic than the measured precision of the pen.

The ceramics and bronzes that use this fluid style of writing show that the Hui contribution was not simply about adding pious inscriptions to distinguish their wares from those next door. The words truly come alive. This new sini script was used in everything from miniature copies of the Qur’an to enormous wall paintings in mosques. In copies of the Qur’an this comes closer to the muhaqqaq style that inspired it, but there are innovations that make it unique. Manuscripts, though written with a wood or bamboo pen, retain the look of brush strokes. The horizontal tails of letters, so distinctive to all Arabic writing, are even more extended in sini. There is also a certain disregard for the conventionally approved connections between letters.

|

|

|

Three incense burners show, top, the deep cobalt blue that is typical of Ming ceramics;

center, a stylized mark of the Zhengde emperor in the lighter blue of the Qing Dynasty and,

lower, a 19th-century design using green enamel and highly stylized sini script. |

In addition to the style of writing, the decoration of Hui Qur’an copies shows innovation in an Islamic context. Traditional Chinese motifs such as cloud bands and peonies proliferate. Colophons giving the place, date and scribe who copied the Qur’an are much rarer than in the Middle East. The oldest known Chinese Qur’an with a colophon dates from the Ming Dynasty. It was copied in 1401 at the Great Mosque of Khanbaliq, the Mongol name for Beijing. The scribe used a format that has been popular in China, and almost nowhere else, for more than 600 years.

Chinese copies of the Qur’an are generally bound into 30 volumes, one for each of the conventional divisions of the text. During Ramadan, Muslims everywhere read one of these sections (juz’) each day. In China, the preference was for community readings with the local imam. Carrying a single, slim volume would have made this easier, especially since Chinese copies are highly legible: Multiple volumes require only three or five lines of text for each page. Complete, 30-volume sets from the past are hard to find, and they tend to look more like an encyclopedia than a copy of the Qur’an.

The most eye-catching Chinese contribution to this art is found on scrolls and buildings. It was in larger formats that sini script came into its own. The most prominent decorative feature of Hui mosque interiors has for centuries been huge inscriptions on the walls. Usually near the mihrab, the niche indicating the direction of Makkah, the shahadah is the most ubiquitous expression of the written word and its power.

With scrolls, the format is identical to mainstream Chinese calligraphy, right down to the finishing touch of red artists’ seals. The main difference lies in the use of Arabic words rather than Chinese characters, although in many cases a Chinese translation is included. Sometimes, the Islamic invocation was written in such a way that the Arabic words actually take on the shape of a Chinese character: “longevity” has been a consistently popular choice.

Another Hui speciality is the use of calligrams, or turning words into images, a practice in the Islamic world since at least the 15th century. The concept was readily adopted in China, where Muslim calligraphers were able to use the scroll format to create images on a large scale. Unlike those in Iran, India and the Ottoman Empire, the calligrams of China avoid figural imagery. Words are instead wrought into such shapes as flower vases and the mighty two-bladed sword known as Zulfiqar. Dishes with peaches were also much admired, presumably owing a debt to the Taoist use of the peach as a symbol of longevity.

In the past, scrolls were displayed extensively in mosques and private homes, but once again the Cultural Revolution stifled a centuries-old tradition. Yet this calligraphy today shows signs of being the hardiest part of the Chinese–Islamic art heritage. The art form has been reinvigorated by artists like Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang, while Islamic bronzes, glass, ceramics and the like remain practically invisible. By opening a window on one rich genre of Chinese Muslim art, perhaps Hajji Noor Deen will inspire the world to enjoy the full tableau.

|

Lucien de Guise (luciendeguise@yahoo.com) is the acting head curator of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur. In addition to writing about art, he has edited the Malaysia’s Best Restaurants guide since 1993. |