|

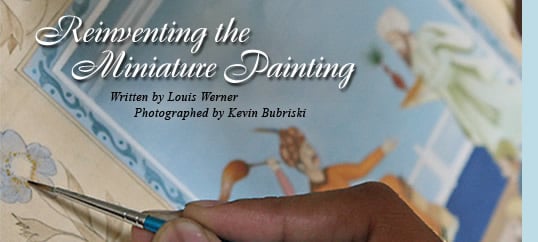

| Using a fine brush that, in centuries past, would have been handmade from squirrel-tail hairs, a student of the miniature tradition begins by practicing the classical techniques. |

|

| Hira Mansoor works while instructor Imran Qureshi critiques another student. “Everything should have a meaning and a purpose,” he says, “but not everything has the same degree of meaning.” |

udyard Kipling’s novel Kim famously begins with the boy hero seated astride a cannon in front of the Lahore Museum, called in Urdu the Aja’ib Gehr, or “Wonder House,” marveling at all that was inside. Today, another kind of Wonder House is just next door to the museum, in the Miniature Painting Department of Pakistan’s National College of Arts (NCA).

udyard Kipling’s novel Kim famously begins with the boy hero seated astride a cannon in front of the Lahore Museum, called in Urdu the Aja’ib Gehr, or “Wonder House,” marveling at all that was inside. Today, another kind of Wonder House is just next door to the museum, in the Miniature Painting Department of Pakistan’s National College of Arts (NCA).

Here, in a two-year intensive program that is a kind of modern karkhana, or Mughal painting workshop, students learn meticulous techniques, including ultrafine figure drawing and brushwork, tea staining of page borders and burnishing of paper surfaces—as well as how to work with such centuries-old materials as brushes made of squirrel-tail hair; handmade, multi-layered paper called wasli; and mussel-shell paint pots. Later, they give their imagination free rein to create new possibilities and new meanings for this highly disciplined tradition, in the context of a contemporary art world where few rules still seem to apply.

In recent years, contemporary Pakistani miniature painting has caught the eye of the international art crowd. There are frequent group and solo shows in London, New York, Paris, New Delhi, Hong Kong and Japan. Shahzia Sikander, a miniaturist and 1993 NCA graduate, won a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (the so-called “genius award”) in 2006, as well as her government’s National Medal of Honor. In the same year, a landmark exhibition of miniatures painted collaboratively by six artists, initiated by NCA teacher Imran Qureshi, had a well-reviewed run at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. In September, the Asia Society in New York will open a major show of contemporary Pakistani art that will include works by several of the country’s top neo-miniaturists.

In recent years, contemporary Pakistani miniature painting has caught the eye of the international art crowd. There are frequent group and solo shows in London, New York, Paris, New Delhi, Hong Kong and Japan. Shahzia Sikander, a miniaturist and 1993 NCA graduate, won a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (the so-called “genius award”) in 2006, as well as her government’s National Medal of Honor. In the same year, a landmark exhibition of miniatures painted collaboratively by six artists, initiated by NCA teacher Imran Qureshi, had a well-reviewed run at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. In September, the Asia Society in New York will open a major show of contemporary Pakistani art that will include works by several of the country’s top neo-miniaturists.

|

| Instructor Imran Qureshi has exhibited his modern miniatures from Pakistan to the US. |

It was, in fact, Rudyard Kipling’s father, Lockwood, who in 1875 founded what is now the NCA, then called the Mayo School of Art, with the intention of training a new generation of creative national artists who could draw on the collection of the Lahore Museum for inspiration. The NCA is now Pakistan’s premier institution granting Bachelor of Fine Arts degrees, and annually some 20,000 applicants seek one of its 150 admission slots; of these, only a dozen or so are chosen for the miniature-painting major.

Qureshi explains that it takes a special sort of student to major in miniatures, as opposed to, say, studio painting or printmaking. First of all, miniature painters sit on the floor all day, holding their paper up close to their eyes, bracing their painting arm against the body. “The hand becomes the palette, shells the mixing bowls. The floor replaces the stool, and the lap becomes the easel,” he says.

|

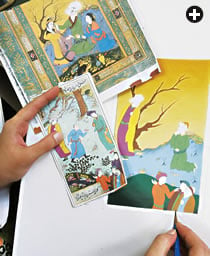

| Rearranging figures from old paintings and adding new ones teaches students elements of composition. |

Minute, repetitive brush strokes render delicate figures in a painstaking technique called pardakht, a kind of linear pointillisme. It’s a far cry from the drips and splashes tossed about by the easel painters in the studio next door. Except for a faint bleeding of sound from students’ iPods, silence reigns in in the miniatures room.

Miniaturists choose their genre for reasons that derive from their personalities. Ayesha Durrani, a 2003 NCA graduate who now teaches first-year drawing, admits to being “a neat freak” who loves miniatures “because they are so civilized.” Rubaba Haider, an ethnic Hazara (an Afghan minority of Persian descent) whose family now lives in Quetta, switched her interest from computer science to painting when she discovered people with “almond-shaped eyes like mine” in her grandfather’s collection of Persian miniatures. The mental discipline required by pardakht, she says, is roughly equal to that demanded by computer programming.

|

| “Painters must place themselves into the tradition without being smothered by it,” says former NCA principal Salima Hashmi, “and still enjoy its delicious rigor.” |

Aisha Abid, a 2008 graduate who admits to being something of a subversive at heart, subverts the miniature-making process itself by building up her wasli paper to a couple of centimeters’ thickness, covering it in imaginary writing, in homage to its former use for manuscript illustration, and then attacking the whole thing with a knife. “I’ve always wondered, ever since I was small, ‘How did the old painters do it?’ I was first intrigued by their technique. Yet I was also afraid of being restricted just to copying their art. It was only when I saw the NCA senior art show that my eyes opened—here was true personal expression within tight bounds.”

Head of the fine arts department Bashir Ahmed, known to his students as “Bashir sahib,” or simply ustad (“teacher”), is the last in a lineage of traditional miniature painters that began at the NCA in the 1940’s with Shaikh Shujaullah, former court painter to the Maharajah of Amber in Rajasthan, and Hajji Mohammad Sharif, former court painter of the Punjabi princely state of Alwar Patiala.

Says Ahmed, “Here we must squeeze the eight years of the traditional apprenticeship into the last two years of a BFA. So we must hurry—but not too much. I always ask my students to slow down the clock, to take four days to make what they think they can do in one. If they do it too quickly, I send them back to take more time. Students are free to use the techniques we give them over the first years to do what they want in the last. But I insist on a firm foundation.”

Says Ahmed, “Here we must squeeze the eight years of the traditional apprenticeship into the last two years of a BFA. So we must hurry—but not too much. I always ask my students to slow down the clock, to take four days to make what they think they can do in one. If they do it too quickly, I send them back to take more time. Students are free to use the techniques we give them over the first years to do what they want in the last. But I insist on a firm foundation.”

Ahmed founded the miniature department in 1985 at the urging of Pakistan’s leading modernist painter, Zahoor ul-Akhlaq, who, as a student at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in the 1960’s, pioneered miniatures in a contemporary idiom. His homage to a well-known equestrian portrait of Emperor Shah Jahan’s three sons by court painter Balchand redrew the human figures into silhouettes and crosshatched out all reference to the landscape, lending it an effect akin to a Jasper Johns flag painting—culturally iconic imagery rendered in a new style that implied instability, even chaotic change. Art historian Virginia Whiles, freelance curator and expert in contemporary Pakistani art, says this painting “played a pivotal role in the reinvention of the miniature” and seeded an effort to “localize modernism” in a Pakistani tradition.

|

| “We must squeeze the eight years of the traditional apprenticeship into the last two years of a BFA,” observes Bashir Ahmed, who founded the miniature department in 1985. |

There is debate among contemporary miniature artists over what Whiles calls “the trap of the copy.” As Shahzia Sikander said at her 2001 Asia Society show in New York, a time when she was working in a more traditional vein, “the entire notion of ‘copying’ needs to be clarified.” Is it, she continued, “understanding the process, or is it understanding the lineage of the medium, or is it mere appropriation? Copying can also mean understanding history. One has to look at someone else’s work very carefully before relating to it in a personal way, in the same sense as claiming a historical past.”

In India today, in contrast to the approach at NCA, miniature painting is taught almost purely as a copyist art for the tourist trade. Only in Pakistan does one find radical innovators like Qureshi painting oversize “miniatures” directly onto the walls of museums, or works like Rubaba Haider’s 2008 senior thesis, a piece she calls mader-e-gul (“My mother, the flower”): an installation of 35 paintings in small, round frames hung from the ceiling waist-high in a walk-through maze, each painting an image conjured from her own emotional responses to her mother’s stomach surgery.

|

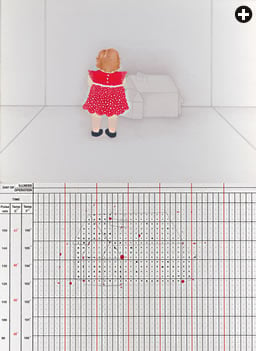

| “Page No. Eleven,” by Aisha K. Hussein, collage and gouache on wasli. |

Or others like Aisha Khalid’s split-screen video that shows, on one side, a Pakistani hand embroidering a rose and, on the other, a European hand pulling out its threads. The piece was inspired by Khalid’s experience at the Royal Academy of Visual Art in Amsterdam, when a European student found her seated on the floor, bent over a miniature, and thought Khalid was doing a performance-art piece—acting out the role, Khalid says with an ironic smile, of an “oppressed maker of women’s work.” This all gets to what Whiles has called “miniature as attitude”—an attempt not to follow the tradition blindly, but rather to converse with it across generational lines.

As wildly creative as NCA miniaturists are invited to become by the time they graduate, their first full year of study is dedicated to the mastery of technique. Teachers Waseem Ahmed and Naheed Fakhruddin, both NCA graduates themselves, oversee their 13 students’ progress not only in pardakht, but also in tappiai, or background color application; layee, or flour-glue paper surfacing and burnishing; and siah qalam, or black-brush work. However, they add with relief, catching one’s own squirrel in Lahore’s Shalimar Garden for brushmaking is no longer required, as it was in the early days.

|

| “It takes a special sort of student to major in miniatures,” says Qureshi. |

Fakhruddin was Bashir’s first student in miniatures, and she is happy still to think of herself as a strict traditionalist. “I learned a lot from him,” she says, “just as an apprentice might learn from the master of a karkhana. I know when to be strict and when to be gentle with my students, when to take their brush in my own hand and when to simply tell them how to do it.” Yet fellow teacher Waseem Ahmed adds an element of free play in his work. One of his pieces depicts the Hindu god Krishna as a denim-clad Bollywood star with a black-gowned Marilyn Monroe as his golden-haired gopi, or cowherd girl.

|

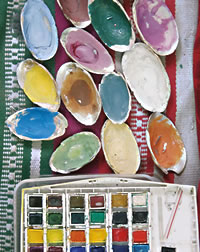

| Mussel shells have long served as mixing bowls for miniature artists. |

In their studio, student Hafiz Salim is working from a photocopy of “Jahangir’s Dream of Shah Abbas’ Visit” by 17th-century Mughal court artist Abu al-Hasan Nadir uz-Zaman. His assignment is to rearrange the figures and insert others from secondary sources, the better to understand the elements of miniature composition: He adds a watching figure taken from the Windsor Castle copy of the Padshahnamah. (Unfortunately, the Lahore Museum’s own miniature collection is frequently rotated off view, so NCA students, contrary to Lockwood Kipling’s wishes, must often use photocopies from other museums as source material.)

Next to Hafiz, Hareem Sultanate is working on a modified copy of a Mughal piece, drawing the wide floral border freehand. “We rarely talk to the students next to us. It is too distracting when we work like this,” she says. Indeed, students sitting closely side-by-side for two semesters, heads always down, seem almost as though they were riding a bus on a year-long journey during which they’re allowed to talk to their seatmate only during tea breaks.

Former NCA principal Salima Hashmi, now head of the visual arts department at Lahore’s Beaconhouse National University, thinks that contemporary miniatures are “defining a problematic identity” in Pakistan. “Painters must place themselves into the tradition without being smothered by it,” she says, “and still enjoy its delicious rigor, something I think is particular to South Asian arts.” Yet she, like many miniaturists themselves, thinks that the international art market often wants to exoticize the new practitioners, and that its expectations can restrict a painter’s development. “Buyers must connect to miniatures’ now-fractured genre history. Although they don’t have to ask ‘What is it about?’—because, after all, miniature painting is still primarily figurative—many people continue to desire a fixed visual paradigm in this free-fall 21st century.”

Former NCA principal Salima Hashmi, now head of the visual arts department at Lahore’s Beaconhouse National University, thinks that contemporary miniatures are “defining a problematic identity” in Pakistan. “Painters must place themselves into the tradition without being smothered by it,” she says, “and still enjoy its delicious rigor, something I think is particular to South Asian arts.” Yet she, like many miniaturists themselves, thinks that the international art market often wants to exoticize the new practitioners, and that its expectations can restrict a painter’s development. “Buyers must connect to miniatures’ now-fractured genre history. Although they don’t have to ask ‘What is it about?’—because, after all, miniature painting is still primarily figurative—many people continue to desire a fixed visual paradigm in this free-fall 21st century.”

Hashmi in fact finds a considerable amount of personal freedom even in classical miniatures, in what she calls a “fusion of refinement and experimentation,” as seen, for example, in workshop accidents and incompletely painted surfaces, unintentional collage effects, overpainted margins and even the occasional drop of perspiration that has fallen from the painter’s forehead onto the paper and then been worked into the design. (This is less common than it used to be, as the miniature studio is the only one at the NCA that is air-conditioned, precisely to avoid such accidents.)

|

| Above: Student Iram Khan at work on her latest project. Below: Part of her series “Hide and Seek.” |

|

Halfway through their final term, the students begin to show their creative sides. Hajra Saeed, a 22-year-old from Lahore, is working on an interactive piece using the newspaper’s puzzle page that has been transfer-printed onto wasli. She plans to write her own clues to solve the puzzle and then, instead of providing the solution in words, to give the answers in the form of miniaturist images. Twenty-five-year-old Noor Ali from Karachi sits in his usual corner, its walls hung with architectural drawings, a portrait of David Hockney and interior design schemes from shelter magazines—all, he explains, aide-memoires for his work that deals with “idealized interior space.” “I like the neatness and calmness of miniature, the close attachment to one’s work,” he says. “You stay still within your own art. It’s complicated, really. The rendering of form itself is most inspiring.” For further inspiration, Noor consults an Urdu-language dictionary of Freudian psychoanalytic terms and reads Gaston Bachelard’s classic text on how to experience the feeling of empty rooms, The Poetics of Space.

Final-year students, in both their crossover projects in other departments and in Qureshi’s individual critiques, are asked to rethink much of what they have been taught. Hira Mansoor’s “linked project” is salt-print photography, seeking common ground with miniaturism’s rigorous technique; Hajra Saeed is making a video of a moving Rubik’s Cube, its faces painted as miniatures. Another student is working on studies in geometry—an echo of miniatures’ often complex architectural settings—by making prints on acrylic plates. The idea is to bring the awareness of other disciplines back to their final semester of intensive miniatures, which culminates in a senior thesis show.

|

|

| The NCA campus, top, is located next door to the Lahore Museum with its Miniature Painting Gallery. A plaque, above, commemorates the school’s first teacher of miniature painting. |

In another corner, Qureshi is critiquing Sajjad Hussein’s portrait of his sister, finely rendered in the pardakht manner. The image floats in an abstracted landscape of gaily colored arcs drawn as receding hills, which are stamped by his sister’s own flower drawings. Qureshi asks Hussein to seek a more personal connection between figure and background. “Everything should have a meaning and a purpose, but not everything has the same degree of meaning,” he says. “Sometimes, after you make a stroke without thinking it through, you should return to it and give it a better reason for being there. Shape it again, with more meaning the second time round.”

Qureshi is firm but gentle, his eye curious for all kinds of art. When visiting London, he says, he always goes to the Tate Modern, yet had his happiest moment at a private appointment at the Victoria and Albert Museum to view the 116 paintings in a precious illustrated manuscript of the Akbarnama, the life of the Mughal emperor Akbar. “It was truly a marvel to hold them in my own hands—no frames, no mat boards. You see so much more.” This appreciation for work of the late 16th century he carries equally to the work of his students.

Ahsan Jamal is a 2003 NCA graduate who has chosen to remain attached to the demanding idiom of small detail and fine technique. Not one for espousing “miniature as attitude,” his is closer in spirit to what Salima Hashmi calls “the submissive nature” of the genre’s technical demands. His series of circular five-centimeter (2") paper discs, painted with psychologically astute micro-portraits of friends and disturbing tiny landscapes of distant horizons, was shown in New York at the Aicon Gallery in the summer of 2008.

For him, the studio is almost a sacred space—or a kitchen. “I relate cooking to making my art,” he says. “Eating fulfills whatever the body craves, as does my painting. I associate certain tastes with certain moods. If I take on a new student apprentice, we start by cleaning the house together. If you see visual pollution, that is what you paint. I am learning the pardakht of my own life—to dance with less movement.”

For him, the studio is almost a sacred space—or a kitchen. “I relate cooking to making my art,” he says. “Eating fulfills whatever the body craves, as does my painting. I associate certain tastes with certain moods. If I take on a new student apprentice, we start by cleaning the house together. If you see visual pollution, that is what you paint. I am learning the pardakht of my own life—to dance with less movement.”

Rashid Rana’s pixelated photomontages, some as large as 2 by 3 meters (7 x 10'), are as far from the scale of Ahsan’s micro-miniatures as one can imagine, yet they too fit within the miniature tradition in their own way. Rana’s “Red Carpet-1”—an overall image of a Persian carpet made up of tiny photographs of a Lahore slaughterhouse—sold at Sotheby’s in May 2008 for $624,000. An earlier photomontage, playfully entitled “I Love Miniatures,” consisted of an image of the Emperor Jahangir, in a classic profile view, made up of tiny photographs of Lahore billboards.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2003 NCA graduate Ahsan Jamal’s series of small, psychologically astute miniature portraits was shown in New York last summer. |

“I like to hold conversations between the micro and macro aspects,” he says. “In the big picture, I let them see what they want to see. In the pixels, I show them what I want them to see. In Pakistan, we have the old always beside the new—a Mercedes and a donkey cart on the same road.”

Rana holds that contemporary miniature is more a movement than a genre and feels that technique alone cannot take the movement forward. He likens this to the dilemma of the Bengal Revival movement at the turn of the 20th century, led by Rabindranath Tagore, which was controversial at the time for breaking with traditional materials and subject matter, and which also spawned many second-rate artists who merely wore the label without adding anything to it.

|

|

| Top: Mussel shells have long served as mixing bowls for miniature artists. Above: The mental discipline of miniature painting is comparable to that of computer programming, says Rubaba Haider, a former programming major. Her thesis project, “mader-e-gul” (“My mother, the flower”), installed 35 paintings in small, round frames that hung from the ceiling in a walk-through maze. |

Meanwhile, new student Sardar Abdul Rahman Khan has big plans to add something new to the tradition of the movement/genre. Just beginning his one-month rotation in the miniature department, he is already certain that it will be his major. Afterward, he says, he wants to design video games. “I’m a big electronic-media guy,” says Sardar, whose family is originally from Afghanistan. “I love playing around with Photoshop, and I’d love to bring miniature painting into video-character design. Some of the stuff out there now is quite poorly drawn.

I could really make it better.”

Video-game design may not be what ustad Bashir has in mind for the pardakht technique that he insists students must master before graduation, but Sardar’s teacher Hasnat Mehmood is all in favor of experimenting with anything at hand. He teaches fine graphite-pencil drawing in miniature style, and tries above all to keep his students from developing a “copyist” mentality. He puts new students through autobiographical exercises, asking them to draw a self-portrait beside a copied classic Mughal figure as a diptych in an invented architectural setting. Somehow, one can imagine Sardar then taking the next step, animating the whole thing on his laptop computer.

|

Kevin Bubriski (www.kevinbubriski.com) is a documentary photographer who lives in southern Vermont. He will be associate professor of photography at Union College, Schenectady, New York, in 2009–2010. |

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World and also writes for El Legado Andalusí and for Américas, the magazine of the Organization of American States. |