This video gallery requires the Flash Player plugin and a web browser with JavaScript enabled.

|

| J. Grimes |

| Many of the Yemenis were hired as firemen, shoveling coal into boilers below decks. |

Having settled in the town in 1894, Said and his fellow seamen, numbering only a few dozen in the period before World War i, were part of a growing contingent of Arabs—mostly Yemenis—who worked on British steamships. These seamen were drawn into the British Empire following the 1839 annexation of Aden, at the southwest tip of the Arabian Peninsula in what is now Yemen. The first colonial possession acquired during the reign of Queen Victoria, the Aden Protectorate was established to provide a coaling station for British ships halfway between Bombay and Suez. Run by the British authorities in Bombay, Aden doubled in size as the rural population of the Yemen highlands was drawn to the improved standard of living that this new colonial center offered. This marked the introduction of an industrial economy in Yemen and established the country’s pattern of rural-to-urban migration that continues today.

|

| Each Saturday, young and old members of the Yemeni community in South Shields gather to provide a meal for the 20-odd retired seamen. It becomes a time for the community to gather, relax and socialize. |

The growth of the world’s fleet of coal-fired merchant ships in the second half of the 19th century required new labor. “Tramp steamers”—ships that plied irregular routes and required crew willing to work for long periods—were unattractive to European sailors. Into this breach Arab workers willingly stepped. The most common position for them was below decks as firemen, where they shoveled coal into the furnaces. It was the most arduous, grueling job on the ship. In the intense heat and constant noise of the boiler room, according to the British seamen’s union leader, one in every 200 firemen went mad.

By 1914, there were several thousand Arab seamen rotating through British ports. Although most were only temporary migrants following work, some settled, and in South Shields—England’s fourth-largest port after London, Cardiff and Liverpool—they became one of Britain’s first substantial Muslim communities.

|

|

|

| Abdul Rahman Geddes |

Nasser Abdul Rahman |

Al-Haj Sabahi |

Because civic authorities feared cultural mixing, seamen of all nationalities were barred by law from residing in private lodgings with local families. Thus seamen required larger, commercial accommodation, and the boardinghouses that were established to meet this need were organized along ethnic lines. As centers for their respective nationalities, they quickly became not just rooming houses but informal homes, service organizations, financial institutions and hubs of the maritime labor network. By 1920, South Shields was home to eight Arab boardinghouses hosting between 300 and 600 seamen at any one time. Today, two boarding- houses still remain, and despite the many transformations of the community and the industry, and despite their declining populations, they continue to play an active role in 21st-century South Shields.

|

|

| Left: Adnan Sayyadi visits with his grandfather Mohammed Sayyadi in Mohammed’s boardinghouse, one of two remaining in South Shields. Right: Norman and Maureen Kaier are among the several thousand residents of South Shields whose families today are of mixed English and Arab heritage. |

For those who sought maritime work in Aden, residents of the Protectorate were readily employable, as they were legally British subjects. Those who lived beyond the Protectorate had to either bribe local authorities to designate them as Protectorate residents or hope that British immigration controls would prove ineffective. During World War i, the latter turned out to be

frequently true, as issues of citizenship were brushed aside in the rush to man the ships in support of the war effort. Being firemen, however, now meant more than working long hours: Because their posts were below- decks, they could only rarely escape from a torpedoed vessel. During what was then called “The Great War,” some 700 Arabs from South Shields lost their lives when their vessels were sunk.

Despite their demonstrated valor, however, the postwar period saw new immigration restrictions on the Arab seamen. Instead of being regarded as returning servicemen or British subjects with rights, they were reclassified as “coloured aliens,” barred from receiving welfare and sometimes deported. With a depressed shipping industry and a labor market bloated by demobilized British service personnel, Arab seamen even became the targets of popular hostility. Although South Shields had been known as “the town where colour doesn’t count,” clashes between Arab seamen and “Britishers” in 1919 and 1930 saw these labor disputes portrayed in the newspapers as “race riots.”

|

|

|

| Abdul Rahman |

Ali Ahmed Ali |

Said Muhamed Ghaleb |

The North East, as the region is known in England, has historically been identified as welcoming. Although, in the 2001 census, some 96 percent of respondents defined themselves as “White British”—compared to 87 percent in the rest of England—this homogeneity hides a history of international migration, particularly in the town of South Shields, which was also a major center for immigrants from Scotland and Ireland, as well as a home for people from

further afield—including the Arab

seamen. By some estimates, more than one-third of the town’s 1911 population was born outside England or born to immigrant parents.

Today, despite the decline of the coal and shipping industries for which they came to work, the Yemeni community of South Shields is neither dead nor invisible. There are around 20 seamen from the older generation still living in the boardinghouses of Mohammed Sayyadi and Muhammed Mohamed, and they remain in South Shields to draw their pensions, which they use to continue to support their families in Yemen. Their place in the region’s culture lives through the communities they helped create, the occasional marriage with non-Yemeni locals and their history of transnational relations that dates back to colonial times.

|

|

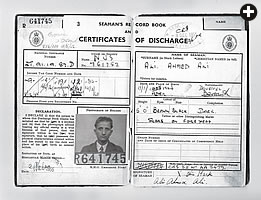

| Left: Ali Ahmed Ali’s discharge record, and, right, the Yemeni seamen’s cemetery in South Shields. |

|

Peter Fryer (peterwfryer@hotmail.com) is a freelance documentary photographer whose work over the past 20 years has focused on community and identity in northeastern England, where he lives, and in Lebanon, Palestine and Yemen. He is represented by Panos Pictures of London. |

|

David C. Campbell is professor of cultural and political geography at Durham University in England, where he is also associated with the Durham Centre for Advanced Photography Studies. His web site is www.david-campbell.org. |