|

| J. Grimes |

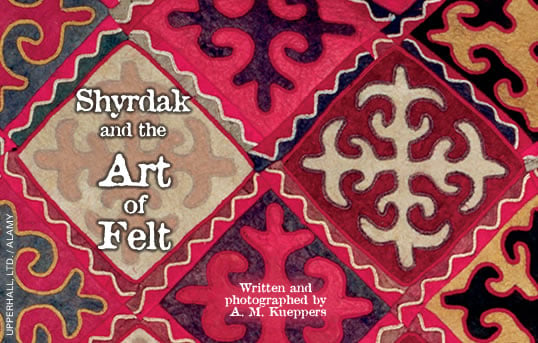

| Top: Kyrgyz shyrdak designs are as symbolic as they are decorative. The rhombus pattern echoes the diagonal wooden latticework of a yurt interior; the four corners of each rhombus represent the four seasons and the four cardinal directions. The trefoil curls are ram’s horns, symbolizing abundance, good fortune and family. Insets, from top: Because it involves bonding fibers rather than weaving them, felting is a simple process. Beating the wool loosens dirt and evens out the fibers. Then, the wool is arranged on a reed mat, and the mat is tightly rolled while hot water, poured from a kettle, softens the microscopic keratin scales on the surface of each wool fiber. The mat is then stepped on and rolled back and forth; it may also be rolled along the road hitched to a donkey. This pressure permanently interlocks the scales, and thus the wool fibers. The resulting felt can be unrolled while still damp; the bonded fibers are virtually inseparable. |

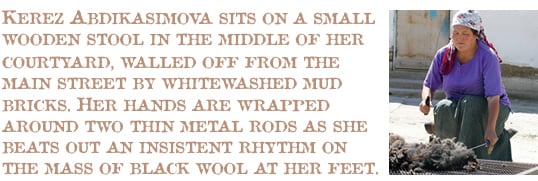

The beating, she explains, separates and cleans the raw wool, sheared from her family’s flock of sheep. The sheep are now grazing in mountain pastures for the summer.

It is the first step toward producing a shyrdak, a colorful Central Asian felt carpet, which, thanks to the Altyn Kol women’s cooperative, is slowly making its way onto the international market.

Archeologists consider felt rugs to be humanity’s first manufactured floor covering, placed on the ground inside yurts and other tents as people journeyed, together with sheep, cattle and horses, across the plains and mountains of the globe.

Today, this ancient craft has all but disappeared, replaced by woven and knotted rugs and, in the last two centuries, by mass-produced carpets and synthetic floor coverings. But in remote nations such as Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, seminomadic people continue to make felt rugs for their yurts and village homes—and, most recently, for tourists.

|

| MARIANNE TUERLINGS / SHIRDAK SILK ROAD TEXTILE |

| The heart shape at the center of this shyrdak symbolizes hospitality; it represents the leather bowl in which hosts offer fer- mented mares’ milk (kumiz) to guests in a traditional Kyrgyz home. |

“I have been making shyrdaks for 40 years, but originally we just did it for ourselves,” 61-year old Abdikasimova tells me in staccato, Kyrgyz-accented Russian. “It’s only in the last few years that we have been marketing and selling them as a product.”

She is one of the founding members of the Altyn Kol cooperative, formed in 1998 with the help of a pair of Swiss development workers living in Kochkor, a midsized town of 16,000 in the center of the country. Kyrgyz for “Golden Hands,” Altyn Kol combines the skills of local shyrdak makers with the business savvy required to market their products in Kyrgyzstan and abroad.

Abdikasimova has retained the stern countenance and military bearing that was required of Soviet schoolteachers. She was one for years, through the days of Brezhnev and Gorbachov and into the early years of Kyrgyzstan’s independence.

Her white and silver headscarf, purple embroidered T-shirt and flower-print skirt are common throughout the region, but her dedication to her craft and the high quality of her shyrdaks set her apart.

Abdikasimova sells about 10 large pieces a year at prices that range from the equivalent of $50 to $150. Though modest by western standards, the income allows her to take a step up Kyrgyzstan’s steep economic ladder.

“I have six children and a pension of about $15 per month. My husband gets $20,” Abdikasimova says. “Even here, that’s not much.”

Like all Altyn Kol members, Abdikasimova keeps 70 percent of the retail price from every sale—but if a rug doesn’t sell, she gets nothing. This arrangement puts quality at a premium. Development workers, diplomats and adventurous tourists are the cooperative’s principal clients.

While international organizations and foreign embassies set up shop in the capital, Bishkek, shortly after Kyrgyzstan declared independence in 1991, tourists have only been trickling in to Kochkor more recently. They are drawn to the region by the Tien Shan mountains along Kyrgyzstan’s western border with China. But inevitably visitors are also enchanted by Kyrgyz culture, much of which reemerged, seemingly unscathed, after 70 years of Soviet rule.

The nomadic Kyrgyz people established themselves in this region long before Genghis Khan swept in from Mongolia in the early 13th century. His forces quickly overwhelmed the local population, which then joined him on subsequent campaigns into China, the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

The Kyrgyz slipped into obscurity under Mongol, Timurid and ultimately Russian rule during the next nine centuries, but their nomadic way of life endured until the early 20th century and the sweeping changes that followed the 1917 Soviet revolution.

|

| Sources of wool, meat and milk for the families that live in the yurts behind them, sheep find summer pasture in a meadow outside Kochkor. |

As a consequence, Kyrgyzstan’s highways are dotted with roadside yurts offering fer-mented mares’ milk to drink, and in the summer months the lush valleys of the Tien Shan host shepherds who protect their livestock from a range of wildlife that includes snow leopards, wolves and eagles.

Ignore automobiles and western dress—and the country’s near–100-percent literacy rate—and it can seem as if little has changed culturally since the days when the Kyrgyz rode with the khans.

Shyrdaks are among the tangible elements of this resilient culture.

The oldest known felts were found in the 1950’s at a tell in Beycesultan, Turkey. Their manufacture, in about 2500 BC, was made possible by a series of innovations that had begun more than 5000 years earlier.

First, humans had to learn how to domesticate plants and animals. In The Mummies of Ürümchi (1999, Norton), Elizabeth Wayland Barber cites archeological evidence that dogs, sheep and wheat were domesticated in Syria by 8000 BC. By 4000 BC, Middle Eastern peoples had also learned how to harvest useful products, such as wool and milk, from their livestock.

“Once they could get both food and clothing from an animal, they were in a position to really exploit the grasslands, so woolly sheep made nomadism possible,” Barber says. “Horses allowed such a large community to stay mobile.”

Sometime around 3000 BC, humans invented felt. Though little used in the modern world, the textile played a key role in the early Indo-European expansion across the plains of Eurasia.

“It can be made so dense as to be nearly impervious to wind and water, yet it is far lighter than other waterproof materials like wood and metal,” Barber writes. “The herders spread great sheets of felt over light frameworks to produce their famous round tents, or yurts, and they use it for flooring (as rugs), bedding, luggage, saddle gear, hats, cloaks, and other clothing.”

Like horses and sheep, felt remains a fundamental part of Central Asian life to this day, although when nomads adopted a more sedentary lifestyle, many cultures switched to weaving and knotting rugs on wooden looms. Others, like the Kyrgyz, continued to travel, rolling and pressing wool into felt on their journeys across the mountains and valleys of the Tien Shan.

Inside Abdikasimova’s sunlit courtyard on a scorching hot day in early July, I return to this ancient world.

Together with Mayram Omurzakova, who also serves as Altyn Kol’s director, Abdikasimova gathers small bunches from a previously prepared pile of wool and spreads them neatly across a reed mat like the ones that cover a yurt’s wooden frame before the thick layer of felt is placed over them. Just as in the yurt camps of a bygone era, shyrdak-making remains a communal activity. Neighbors stop by to visit, and Abdikasimova quickly cajoles them into helping out.

She briskly assigns her son Bakit, my driver, Maksit, and another neighbor to help her roll up the wool, still on the mat, into a tight cylinder, carefully pouring boiling water onto it. Then they roll and stamp on the rolled-up mat for half an hour, pressing the wet wool into felt.

For larger pieces, it is easier to do this pressing by rolling the mat along a road. Young boys riding donkeys, pulling a rolled-up shyrdak mat, are a common sight along Kyrgyzstan’s highways.

|

|

| After tracing a design in chalk, Abdikasimova cuts it out and sews it to the background. “Every shyrdak has a front and a back, and every shape is used twice, the positive and the negative,” she says. |

“We are used to making bright-colored shyrdaks for ourselves,” Omurzakova tells me. “But the Swiss noticed that foreigners wanted more natural colors, so we began making more black and white shyrdaks and also experimenting with natural dyes.”

“The Swiss,” Walter and Susanne Schlaeppi, were one of the first non-Kyrgyz couples ever to live in the town, a three-hour drive from Bishkek. It was in 1995, just four years after Kyrgyzstan’s independence, that they rented a house near Kochkor, where they lived for five years. “We bought a shyrdak for the house in about January 1996,” Susanne tells me later by phone. “Word traveled like a fire through the village and across the whole valley: ‘The Swiss are buying shyrdaks!’”

Poverty has been rising in Kyrgyzstan since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, with rural areas the hardest hit. World Bank statistics show 35 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, and 2008 per-capita gross national income was $780 a year. One side effect of this change has been a return to a more traditional way of life and a resurgence of Kyrgyz handicrafts.

But uncomfortably, perhaps inevitably, some Kyrgyz looked to the Schlaeppis for instant relief.

“After we bought the first carpet, we wanted to use another to insulate the wall,” she recalls. “So everyone thought we would just keep buying them, and every day people stood outside our house with a carpet and a story about a sick daughter or other family problems.”

Realizing she could never afford to buy all the shyrdaks, Schlaeppi instead took down every artisan’s address.

That spring, together with a small group of local craftswomen, she organized an exhibit at the National Museum in Bishkek, gathering carpets from all the women who had stood on her doorstep that winter.

That spring, together with a small group of local craftswomen, she organized an exhibit at the National Museum in Bishkek, gathering carpets from all the women who had stood on her doorstep that winter.

“The first exhibition was a big success. It was all the foreigners who were buying,” Schlaeppi recalls.

Her goal had never been to run a business, so every year she did less and less, allowing the women from Kochkor and other regions to take over.

In 1998, about 200 of the women formed Altyn Kol, and they put Omurzakova in charge. The cooperative now has close to 1000 members. Exhibitions are held twice each year in the National Museum, and Altyn Kol now exports rugs and other felt handicrafts to Switzerland, Austria and the Netherlands.

|

| MARIANNE TUERLINGS / SHIRDAK SILK ROAD TEXTILE |

| Trefoil ram’s horns make up most of this pattern, which is also bounded on the outer edge by triangles that symbolize Kyrgyzstan’s mountains. |

Marianne Tuerlings, owner of Amsterdam’s Shirdak Silkroad Textile, has been selling the felt rugs for the past nine years.

“Only collectors buy the bright, traditionally colored shyrdaks,” she says. “But I also have customers who are interested in interior design, and you can combine shyrdaks with furniture of simple design.”

While her neighbors stamp the carpet, Abdikasimova sits down amid her works in progress—a pile of black, gray, maroon, green, red and white felt pieces. She draws shapes on them in white chalk and cuts out the shapes.

“Every shyrdak has a front and a back, and every shape is used twice, the positive and the negative,” she says. “Both the design I cut out and also the piece I cut it out from will be used.”

All the patterns are symbolic, though interpretations of the signs vary. She holds up a variety of brilliant designs—a red-and-green moon shape, a blue hawk’s foot and a black-and-white ram’s horn—before stitching a purple crow’s-foot pattern into a maroon background.

She returns to the new rug for about 20 minutes, working intently on it, then decides it is time to unwrap the wet felt from the reed mat. Together with another neighbor, Saina Baichekirova, she unties the string holding the coil together and reveals a wet, gray sheet of felt. After it is fully unrolled, the two women crouch down on their hands and knees and rub the textile with their forearms. This further dries and softens the wool—and leaves shyrdak-makers with rug burns on their forearms for the whole summer.

“That’s enough,” Abdikasimova says. She is now sweating beneath her headscarf. “Now we’ll tie it up again, put some more water on it, and then let it dry out.”

Over the next month, she will dye the new felt, or perhaps leave it in its natural color, and cut shapes into it to make another shyrdak. As I say goodbye, Abdikasimova returns to her sewing. I walk out past a curious little girl who’s peeking into the courtyard where, one day, she too may continue the craft of making shyrdaks.

| Journalist A. M. Kueppers (amkueppers2008@gmail.com) has traveled widely in the former Soviet Union to report for British and North American publications. “Shyrdaks first caught my eye at the central market in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, but as I researched the story, I found out that they are much more than beautiful souvenirs—they are living pieces of the nomadic past.” |

Links:

Altyn Kol cooperative: www.altyn-kol.com (includes a glossary of shyrdak symbols)

Shirdak Silkroad Textile: www.shirdakshoponline.com |