|

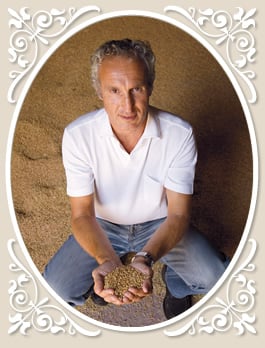

| “Rice was first planted in northern Italy on our farm,” says Count Paolo Salvadori di Wiesenhoff (above) whose Principato di Lucedio (top) was founded in 1123 as a French Cistercian abbey. Buffered by the Alps against north winds and fed by ample rivers, rice thrived in the Po Valley’s clay-rich soil and warm, humid summers. |

I was standing in the Principato di Lucedio, producer of some of the finest rice in Italy and, according to its proprietor, Count Paolo Salvadori di Wiesenhoff, also its first rice producer. The Principato (“Principality”) lies on the Vercelli plain, between Milan and Turin, below the northern slopes of the Piedmontese hills. It was early July, and the rice sprouted knee-high out of fields that had been flooded since spring. The rice would grow until autumn when, heavy with golden grains, it would be harvested.

Oryza sativa—rice—began its long journey to Italy in China and East Asia, where it has been cultivated since approximately 6000 bc. It spread slowly to India and Southeast Asia, and it is likely that it was Persians who carried it from India to the Middle East. From there, Arabs introduced it into Egypt’s Nile Delta around ad 600. In the seventh and eighth centuries, rice followed the expansion of Islam, and the agricultural revolution brought by the Arabs, to North Africa, southern Spain (al-Andalus) and, from there, to Sicily, France, Portugal and Italy. But in the north of Italy, rice has had a more enduring impact than anywhere else in the Mediterranean, for it has transfigured the landscape, the economy, the cuisine and even the region’s people.

Rice did not arrive alone on the northern shores of the Mediterranean: The Arabs also introduced lemons, oranges, eggplant, artichokes, sugarcane, pomegranates, watermelon, figs and spices. Nor did rice arrive entirely a stranger: The Romans knew rice, but only as an expensive import for medicinal uses.

In the wetlands south of Valencia, the Arabs of al-Andalus built some 8000 noria, or waterwheels, and rice was among the crops that have flourished there ever since. Ibrahim al-‘Awwam, an agriculturist in Seville during the 12th century, wrote in his Kitab al-Filaha (Book of Agriculture) about the seasonal phases of rice farming, its needs for irrigation and drainage, how to fight parasites and how to harvest and store the crop. Al-‘Awwam’s statement of the best way to cook it—with butter, oil, fat and milk, he wrote—is one of the earliest references to preparing rice in the Mediterranean region.

|

| It took some 5000 years for rice to reach northern Italy from China via India, Persia, the Middle East and Sicily—though exactly who provided it to the monks of Lucedio remains unknown. The Po Valley region now grows more than half the rice produced by the European Union, and much of it is traded here, in Vercelli’s Borsa Merci. |

Following the Muslim conquest of Sicily in the ninth century, rice was grown and exported from there by the 10th century. Although risicoltura—rice growing—gradually died out in Sicily, it is likely that it was from there that production moved north to the moist, flat and fertile Vercelli plains.

In 1123, Cistercian monks from Burgundy, France founded Lucedio Abbey and began to dig channels to get water moving through the marshy land. By the end of the 15th century, documents show they farmed 2700 hectares (6670 acres), and of those, 1732 grew rice—about one-third of the Vercelli plain’s rice production at the time and more than three times what the Principato grows today. By the mid-16th century, rice cultivation in the region had grown to around 50,000 hectares (123,550 acres).

In 1123, Cistercian monks from Burgundy, France founded Lucedio Abbey and began to dig channels to get water moving through the marshy land. By the end of the 15th century, documents show they farmed 2700 hectares (6670 acres), and of those, 1732 grew rice—about one-third of the Vercelli plain’s rice production at the time and more than three times what the Principato grows today. By the mid-16th century, rice cultivation in the region had grown to around 50,000 hectares (123,550 acres).

The expansion of rice was opportune, for bubonic plague had ravaged Italy, mainly in the mid-14th century. Rice, with higher nutritional content than millet, rye, sorghum or barley, was among the foods that helped nourish society back to strength. In addition, rice produces more food energy and protein per hectare than wheat, corn (maize) or barley, and its harvests are more dependable.

In 1784, Pope Pius iv secularized Lucedio Abbey. The estate passed through successive owners, including the House of Savoy and Napoleon Bonaparte, and in 1822 was split among three investors. One was an ancestor of Count di Wiesenhoff, the current owner; another was the father of Camille Cavour, whose name is attached to an 85-kilometer (53-mi) canal, finished in 1866, that more than doubled the area under rice cultivation in the region. Cavour himself died five years before the completion of what is now considered the most important water engineering project in the region, following a career in which he served not only as longtime prime minister of Piemonte, but also as the first prime minister of a united Italy.

|

| This farm advertising rice production and sales near Vercelli is one of more than 4500 rice farms throughout Italy. |

The canal had effects beyond the region. Giuseppe Sarasso, a Vercelli agronomist and chairman of the Italian rice exchange, says Cavour had two goals: “Irrigation and industrial revolution. The second begins with water flowing.” Engineers installed small turbines at water gates along the canal to produce electricity, and it became, to Spanish historian Rosa Tovar, “one of the principal sources of wealth and [the] motor of the region’s enormous economic development.”

Today, Italy produces more than half the rice in Europe, and the provinces of Vercelli, Novara and Pavia account for 93 percent of that. Italy exports more than half of this production, mainly to northern Europe, Turkey and Syria.

|

| From top left: Among Italy’s more than 100 varieties of rice, the short-grained carnaroli, balto, vialone nano and arborio rices are the most popular among northern Italians, who eat almost twice as much rice as the average European. |

Vercelli, a handsome, prosperous city of 45,000 a few minutes’ drive from the Principato, is the capital of Italian rice. Near its medieval Torre dell’Angelo, which presides over the Piazza Cavour, the old market square, is an early-1970’s building housing the Borsa Merci, the Vercelli rice exchange.

“We trade half of all Italy’s rice here,” Sarasso says, standing above the 51 tables in the marble-floored hall where farmers and their agents meet millers to sell harvested rice. A large computer screen at one end displays current prices. Trading takes place on Tuesdays and Friday mornings, and after trading each Tuesday, a group of eight representatives meets to set the week’s minimum and maximum prices, which become the European standard.

More than 100 varieties of rice grow today on the Vercelli plains, though the most traditional, and the most sought-after, are japonica short-grain varieties. Arborio is the best-known outside Italy, largely because it was the first to be exported. Bulky, starchy baldo and stocky vialone nano are local favorites, while Italian chefs regard carnaroli to be king of the rices, with its large, highly absorbent grain that holds its shape and texture while cooking—making it perfect for the region’s most celebrated dish, risotto. (See “Risotto,” sidebar.) Thanks to the popularity of savory risottos and rice-based summer salads studded with garden vegetables, northern Italians consume about nine kilograms (20 lbs) of rice a year per person—three times that of southern Italians and nearly double the European average of five kilograms (11 lbs).

|

| Until the 1970’s, the Vercelli rice harvest depended on women who worked as seasonal harvesters, called mondine. In the 1940’s and 1950’s, Elvira Fusaro and Carla Varalda worked at Lucedio during the six-week harvest. They recall being paid not in money, but in rice. Meals were rice with beans. “Twice a week we ate pasta,” Fusaro says. Varalda recalls the long walks back and forth from the fields and the strain on her back, which still bothers her. “The work was hard,” Fusaro says, “but we sang all the time. And at night there was music.” Both met local men during their mondine days, married and have remained near Lucedio. |

It was not only canals, however, that made the region’s rice possible. From the mid-19th century until the early 1960’s, the muscle for rice transplanting, weeding and, to a lesser extent, harvesting came from women known as mondine (“rice weeders”). In early summer, they arrived as seasonal workers, mainly from small mountain villages, and for about 40 days they replanted rice and weeded the paddy fields, sleeping at night in barracks on straw mattresses, and taking much of their pay in rice from the previous harvest: The standard wage was one kilogram (35 oz) per day of work.

And the work was strenuous. Mondine stood bent over, thigh-deep in sluggish water under the summer sun. Transplanting required more skill than weeding: It meant walking backward, bent over, with the weight on the spine, while using both hands to distribute the sprouted rice.

The peak of the mondine era came during the Korean War, when the global demand for rice skyrocketed. In the spring of 1953, the mondine numbered 157,000, and some 63,000 came from outside the region. But a decade later, Sarasso explains, “women were leaving this type of physical, outdoor work for factories, where the conditions were better.” He shrugged his tall frame. “Farmers had to replace them with technology.” In 1964 there were just 24,000 mondine.

The peak of the mondine era came during the Korean War, when the global demand for rice skyrocketed. In the spring of 1953, the mondine numbered 157,000, and some 63,000 came from outside the region. But a decade later, Sarasso explains, “women were leaving this type of physical, outdoor work for factories, where the conditions were better.” He shrugged his tall frame. “Farmers had to replace them with technology.” In 1964 there were just 24,000 mondine.

On Lucedio, mondine stopped coming altogether in the 1970’s. Now, harvesting that once required 500 mondine is accomplished by only five people, and it’s the same story on rice farms across the plains.

But the legacy of the mondine lives on. During those years when women traveled infrequently, the work in the rice paddies of the Vercelli plain offered a rare chance for communities to intermingle. As a result, some mondine from outside the region married and stayed on the plains, and their families are residents today. Rice, brought centuries before, helped mix the region’s bloodlines.

On the July day I visited the Principato di Lucedio, the mondine would have been nearing the end of their short season’s work. But I saw only the occasional tractor in the fields. Only the frogs wade among the green shoots now.

|

The writing, recipes and photographs of longtime Barcelona resident Jeff Koehler (www.jeff-koehler.com) have appeared in Saveur, Gourmet, Food & Wine, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, dwell, Men’s Journal, Afar, and Tin House. His new book, Rice Pasta Couscous: The Heart of the Mediterranean Kitchen (2009, Chronicle Books) has been nominated for a Gourmand World Cookbook Award. |