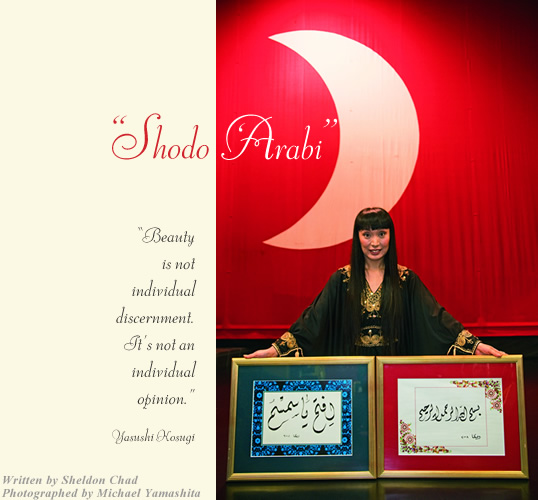

| Choreographer, dance instructor and Arabic calligrapher Ko Reika stands with two of her pieces. Left: An ink pot and pens cut from bamboo lie on top of a work in progress in the studio of Japan’s leading master calligrapher of Arabic, Fuad Kouichi Honda. |

nside the Arabic Islamic Institute in Tokyo, 15 students of calligraphy raptly practice writing verses from the Qur’an. Yet when the call to prayer is heard, few stir. The instructors and students are Japanese, and only two are Muslims. Here, their calligrapher’s pens (qalam in Arabic) are not made of reeds, as is traditional in much of the Islamic world. Nor do they use the brushes (fude) favored by Japanese calligraphers. Their pens are made of bamboo, which is plentiful in Japan.

nside the Arabic Islamic Institute in Tokyo, 15 students of calligraphy raptly practice writing verses from the Qur’an. Yet when the call to prayer is heard, few stir. The instructors and students are Japanese, and only two are Muslims. Here, their calligrapher’s pens (qalam in Arabic) are not made of reeds, as is traditional in much of the Islamic world. Nor do they use the brushes (fude) favored by Japanese calligraphers. Their pens are made of bamboo, which is plentiful in Japan.

For centuries, educated Japanese have been taught the traditions of calligraphy beginning in grade school. At the Nitten, the annual arts exhibition in Osaka, calligraphy is important enough to merit its own section. An appreciation of calligraphy is a lifelong interest for many Japanese, and for some, acquiring proficiency at it is a lifelong study. Yet, over the past two decades, a few have quietly put down their fude and picked up a bamboo qalam to try their hand at calligraphy in Arabic, which, they often find, is not as alien as they had thought.

Yukari Takahashi, who owns an elegant Tokyo nightclub, holds up a sheet of Japanese rice paper with embossed floral patterns framing immaculate calligraphy. I ask her why she studies Arabic calligraphy, and, in her limited English, she answers, “Very beautiful.” Other practitioners—a retired consul-general, a choreographer and dancer, the head of the Tokyo City Retirement Fund—also mention beauty first when describing their attraction to Arabic calligraphy.

|

| Koichi Yamaoka (second from left) is Honda’s partner in the Japan Arab Calligraphy Association. In Yokohama, he teaches calligraphy to students including, from left to right, Rieko Hayakawa, Maryam Yumi Tominaga, Mayumi Kobayashi, and Miyuki Mori. The Istanbul-based Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture has recognized both Tominaga and Kobayashi with awards. |

Admiration runs in the other direction, too: In 2007, at the most recent international calligraphy competition of the Istanbul-based Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture (ircica), four Japanese entrants won prizes.

“It was a pleasant surprise…to see works of a satisfactory or promising level of success coming from a [country] where the tradition of Islamic or Arabic calligraphy is not yet established,” says Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu, secretary general of the Organization of the Islamic Congress. “It is evidence of an emerging interest in and development of this art that is rather unexpected. It gives us pleasure.”

Halit Eren, the director general of ircica, expresses his own amazement by turning the tables: “Would it not be a pleasant surprise if an Arab won an award in Japanese calligraphy?”

|

| Yamaoka also teaches this class in Osaka. |

Al-khatt al-‘arabi —Arabic calligraphy—comes in several styles and has long been regarded as one of the highest Islamic art forms. In Japanese, the word shodo refers to “the way of writing,” which means the stylized drawing of pictographs in kana (Japanese script) or kanji (Chinese characters). Thus Japan’s acknowledged master of the art, Fuad Kouichi Honda, calls the Japanese forms and practices of Arabic calligraphy shodo ‘arabi—“the way of Arabic writing.”

50-minute train ride from the urban whirl of Tokyo, another Japan starts to lay itself out, revealing blue coastline and lush green hills. You arrive in Zushi, where Honda lives with his wife, Mitsuko, a kimono-dyeing artist.

50-minute train ride from the urban whirl of Tokyo, another Japan starts to lay itself out, revealing blue coastline and lush green hills. You arrive in Zushi, where Honda lives with his wife, Mitsuko, a kimono-dyeing artist.

Downstairs is Honda’s studio, and on the floor is a work in progress, paper strips of penciled calligraphy lying jumbled atop a large blue background.

|

| A calligraphic painting by Mayumi Kobayashi. |

“My work is very different from traditional calligraphies,” he says. It consists of an Arabic text surrounded by illumination of geometrical or natural forms, often made on marbled paper, which he calls by its Turkish name, ebru.

“According to my idea, I consider the most suitable design and color to match with the meaning of the words. This [Qur’anic chapter] Surat Ya-Sin praises the greatness of God. I use this very deep, profound blue, ultramarine blues, and there are many lines over these blues like in the depth of the sea or in the middle of the universe. This blue color does not stand for something concrete, but is an image of my expression.”

Honda, who in 1999 received an ijaza (diploma) in calligraphy from the Turkish master Hasan Çelebi, vouches for the traditional cursive diwani jali script he’s chosen for the piece. “We don’t break the existing rules. I cannot overcome the traditional shapes.”

When asked about the cultural value behind a Japanese appreciation of Arabic calligraphy, Professor Yasushi Kosugi’s simple reply echoes the calligraphy student’s: “Beauty.” “Because that is the target,” he says. “We have to attain the beauty.”

We’re sitting in a lounge at Kyoto University, where Kosugi heads graduate studies in the Islamic world and serves as president of the Japan Association for Middle East Studies.

|

| Chieko Kinoshita travels from her home in Hiroshima to Yamaoka’s class in Osaka on the shinkansen, or bullet train. “Just the letters themselves are beautiful. Some kind of art. Maybe art is the most important part,” she says. |

|

| Yasushi Kosugi of Kyoto University is head of the Japan Association for Middle East Studies. |

“Beauty is not individual discernment,” he continues. “It’s not an individual opinion. Shodo is an art based on the collective sense of beauty.

“Another element of Japanese culture is curiosity for things foreign,” he adds.

It was during the 1970’s that the Japanese came into regular modern contact with Arab cultures, and with it came their first modern look at Arabic calligraphy.

Japanese shodo, he explains, has “at least 10,000 letters. Now you find Arabic calligraphy. Wow! What is this? The same way of attaining beauty, but in a drastically different manner.”

In Kosugi’s opinion, in “extent, depths and energies,” Arabic and East Asian calligraphies are the two greatest historic writing traditions of human history.

very two weeks, Koichi Yamaoka, who is Honda’s partner in the Japan Arab Calligraphy Association (jaca), takes a shinkansen bullet train from Yokohama 600 kilometers (375 mi) west to the historic heartland of Japan—the cities of Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe—where he teaches Arabic calligraphy classes. As the train whizzes along, Yamaoka says, “People don’t know about Islam. They only know Muslim people can marry four wives; they don’t eat pork…. Only superficial knowledge. So when I teach Arabic calligraphy, I explain the background of the culture.”

very two weeks, Koichi Yamaoka, who is Honda’s partner in the Japan Arab Calligraphy Association (jaca), takes a shinkansen bullet train from Yokohama 600 kilometers (375 mi) west to the historic heartland of Japan—the cities of Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe—where he teaches Arabic calligraphy classes. As the train whizzes along, Yamaoka says, “People don’t know about Islam. They only know Muslim people can marry four wives; they don’t eat pork…. Only superficial knowledge. So when I teach Arabic calligraphy, I explain the background of the culture.”

Yamaoka spent four years in Saudi Arabia in the early 1980’s. A decade later, he started learning Arabic calligraphy. Recently, he took early retirement from his company to help jaca. “I decided to make some business with this Arabic calligraphy in Japan. I think I can do something.”

In Kyoto, which for a thousand years was the seat of Japan’s imperial court, his advertisement reads, “Welcome to the World of Arab Calligraphy. First Thursdays. Time 2:45 to 4:45. Fee 4200 yen per month. Two classes.”

Today, only three women are here, as they have been for the last year and a half. They share a delicious matcha roll—a green-tea cake—as they do their calligraphy and talk about their art, their lives and their children.

“We try to match the feeling of Arabic calligraphy,” says Manami Ali Syed. She says they are all dedicated to “building the pillar of Arabic calligraphy. Arab culture, Arabic calligraphy and Arabic language.”

At Yamaoka’s class in Osaka, I’m surprised to see Chieko Kinoshita, a woman I had seen in a Tokyo class just a few days before. She’s again unfalteringly drawing the madd lengthened stroke in the middle of the Fatiha, the opening verse of the Qur’an, time after time. I’m surprised to learn she is an office clerk from Hiroshima, which is some 850 kilometers (530 mi) and five hours’ journey from Tokyo. To come to Osaka today, she’s traveled 350 kilometers (215 mi). She is, Yamaoka says, “a very dedicated student.”

To her, “Just the letters themselves are beautiful. Some kind of art. Maybe art is the most important part.”

Yamaoka adds that it’s often difficult for students to put their motivations into words. “It’s quite difficult to explain the meaning of the life, of the fun, of the hobby. Some people have their history; some do not. Some just have feeling.”

or Honda, it was a feeling that came slowly. When he graduated from Tokyo University of Foreign Studies in 1969, he says, “I made up my mind never to open an Arabic book again. I hated the Arabic language; I hated the professors. They only taught grammar; reading Arabic novels [was] impossible!”

or Honda, it was a feeling that came slowly. When he graduated from Tokyo University of Foreign Studies in 1969, he says, “I made up my mind never to open an Arabic book again. I hated the Arabic language; I hated the professors. They only taught grammar; reading Arabic novels [was] impossible!”

But five years into his first job, Honda’s reluctant skills earned him a post in Saudi Arabia. There, the difference between colloquial Arabic and the classical, written Arabic of his studies stumped him. But he had both curiosity and perseverance on his side.

“Every day I would go to the suq [the market] and communicate with the local people. ‘Please, what is this?’ I registered all the words in katakana, Japanese letters. I believe my teachers in the true sense were ordinary citizens, like drivers, clerks, instead of Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.”

Honda soon was so proficient that he was selected to lead a mineral-resources survey team run by the Saudi Ministry of Petroleum. The next three years he spent almost entirely in the desert, where his companions were largely Bedouins. “I became sensitive to the changes in nature.

“When I looked at the desert area, the Rub’ al-Khali [the Empty Quarter] in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula, I was amazed at the beauty of the movement of the desert, the natural flow of sand dunes, like living beings. I looked at my feet. A beautiful print made by the movement of the wind like a fingerprint. I thought [they were] very similar to the movement of Arabic calligraphy, Arabic letters. So when I came back, the vivid memory remained in my brain, especially the beautiful landscapes of the desert. The beauty of the sand dunes and the calligraphy combined together in myself.”

Soon after returning, in 1979, Honda embraced Islam and took the Muslim name Fuad (“Heart”). He taught Arabic, and he taught himself Arabic calligraphy. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, he emerged onto the world calligraphy scene.

|

|

| Yukari Takahashi owns an elegant Tokyo nightclub and studies calligraphy with Yamaoka. |

n the studio of Taisho Eguchi, a master calligrapher and a judge at the Nitten, Yamaoka wields a knife to fashion a bamboo qalam on the spot from the handle of a fude. Eguchi goes over to jars and jars of fude and picks out one made of mongoose hair. He bows ever so slightly to Yamaoka.

n the studio of Taisho Eguchi, a master calligrapher and a judge at the Nitten, Yamaoka wields a knife to fashion a bamboo qalam on the spot from the handle of a fude. Eguchi goes over to jars and jars of fude and picks out one made of mongoose hair. He bows ever so slightly to Yamaoka.

Eguchi is the product of a long chain of masters and schools of calligraphy. He has been a student of shodo for 60 years, and I have come to his studio in Osaka to better understand the “shodo” part of shodo ‘arabi.

But Eguchi has never seen Arabic calligraphy. Yamaoka kindly offers to demonstrate it. Eguchi, dressed in a modest gray cardigan, laughs at my very presence. “I’ve been to America before and I visited some cemeteries. On the stone, there’s only printing, not handwriting. So I think American, European people haven’t much interest in ‘the line.’”

He explains his critique: “I think the wabi sabi is inside the line. When somebody writes the line, the line shows the man himself.” (Part sensibility and part esthetic, the concept of wabi sabi is central to the Japanese understanding of beauty. It defies simple translation: “Transience,” “simplicity,” “ambiguity,” “imperfection” and even “entropy” all touch its meaning.)

Eguchi realizes it’s better to show than to tell. Yamaoka grabs a piece of thick glossy white paper, and Eguchi takes a long piece of washi paper.

|

| In his studio, Honda displays some of the large, colorful calligraphic works that have won him worldwide recognition. In the 1980’s, he spent three years leading mineral surveys in the deserts of Saudi Arabia, and when he returned to Japan, he says, “The beauty of the sand dunes and the calligraphy combined together in myself.” |

In terms of their choices of paper, the Arabic and the Asian calligraphers seem to have changed places over the millennia. Originally, papyrus was used in the Middle East; its rough surface did not lend itself to the precision of calligraphy. It was only with the invention in China of polished paper that Muslim calligraphers were able to perfect the smooth flow of the lines in cursive scripts. But Eguchi’s washi paper is rough, its fibers visible on the surface, much like papyrus. It drinks in the ink unevenly, giving his kanji variable textures.

|

| Taisho Eguchi, master of traditional Japanese calligraphy, demonstrates the rapid, flowing motions of Japanese calligraphy with a fude, or brush |

Eguchi dips his fude—one dip—into the ash-black ink. He angles over the table and, in a controlled flurry, moves top to bottom: one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight strokes, in order, of kanji. Then he writes his signature in smaller characters, using the same brush. It is all over in 10 seconds. (A serious work, he says, like the one in the Nitten, can take up to four minutes.)

Yamaoka sits down and dips his bamboo qalam. He fixes his hand on the paper, aligning the bottom of it and the flat of the angled nib on the paper, and starts writing. Slowly. Deliberately. One can hear the nib scratching the paper: It could be a bird chirping in the distance. Even with small strokes, he goes back and dips the qalam for more ink. It ends not

Yamaoka sits down and dips his bamboo qalam. He fixes his hand on the paper, aligning the bottom of it and the flat of the angled nib on the paper, and starts writing. Slowly. Deliberately. One can hear the nib scratching the paper: It could be a bird chirping in the distance. Even with small strokes, he goes back and dips the qalam for more ink. It ends not

with a flourish but with a thoughtful punctuation mark.

For the first time in Eguchi’s life, he sees a 1300-year-old kanchi (Chinese poem) and a 1400-year-old surah from the Qur’an side by side. Even to the untrained eye, the two pieces of calligraphy trigger emotions from contentment to joy to awe.

Eguchi, however, maintains that “shodo is not art,” and that “ninety-five percent of the importance is in the space between the letters. Five percent is the ability to read the kanchi. Shodo is mainly about the atmosphere of the design.”

hen I ask professor Yasushi Kosugi about this, he maintains that the growth of shodo ‘arabi is evidence of cultural affinity.

hen I ask professor Yasushi Kosugi about this, he maintains that the growth of shodo ‘arabi is evidence of cultural affinity.

“Japan has been taking from world civilization for at least 2000 years,” he says.

“We cut the pen by our own hand out of bamboo, which is very highly esteemed as a plant in this country for traditional art,” says Kosugi. “I think that immediately corresponds to the value of the reed pen in Arabic calligraphy…. [Shodo ‘arabi] is something that can be achieved only by Japanese. Because I see the amalgamation of what is ultimately Japanese—the pursuit of beauty—with that kind of Arab calligraphy.

“I believe that explains why the lady from Hiroshima comes so far, twice a month, to her lesson. In earlier days, in the Tang era, we used to send students to China from this tiny island in pursuit of beauty. The beauty itself is truth.”

|

|

| Yuriko Koike, who has served as Japan’s minister of defense, credits her father’s work in the oil business with her decision to attend the American University in Cairo. |

he Web site of one of Japan’s leading politicians features a pair of dancing robots. They’re dancing to Arab music.

he Web site of one of Japan’s leading politicians features a pair of dancing robots. They’re dancing to Arab music.

|

| The Arabic Islamic Institute in Tokyo. |

“They are very cute, right?” says Yuriko Koike, who served as Japan’s environment minister from 2004 to 2006 and defense minister in 2007. She currently directs public relations for the Liberal Democratic party, and some believe she could one day become Japan’s first female prime minister.

“I try to keep people’s eyes on the Middle East, because the area is so essential to Japan.”

In her office, the Arabic word shams (“sun”) is splashed on a large framed canvas.

“I just pick up my old brush and ink and write my favorite words in Arabic. That’s all. I don’t care whether the words can be read or not, because it’s art. I am just in love with the Arabic letters, and I have no time to learn the old classical rules of calligraphy. I’m just enjoying it for myself. It’s my hobby.”

Koike’s father, an oil trader, sparked her fascination with the Middle East with souvenirs from his travels. Koike went on to study at the American University in Cairo, and she still uses Arabic when she attends international conferences related to the Middle East and when she is interviewed on Arabic-language television.

|

| Koichi Yamaoka, who took early retirement to devote himself to calligraphy instruction, offers guidance to students Tomoko Fujii and Keiko Narita. “When I teach Arabic calligraphy, I explain the background of the culture,” he says. |

Koike only started practicing calligraphy after returning to Japan from Egypt and working as a television newscaster. “As a tv-caster, as a politician, I’m always requested to write something or sign an autograph, and I felt that an ordinary autograph by me in Japanese is not interesting. So I invented,” she says. It is common, she adds, for Japanese not only to sign a name in an autograph but to add some favorite word or letter.

“This is the way,” she says, tapping on a typical autograph pad with the words salaam and shams written on it. “I started using [these] Arabic letters rather than writing Chinese kanjis. People love it. This is my style.”

She delicately opens a wooden box and unwraps an object within. When she travels abroad on state business, she says, “I bring my own souvenir. When I went to the United States to Arlington [National] Cemetery, everybody who visits there officially is asked to bring some typical souvenir.” (American soldiers, including many who fought Japan in World War ii, are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.)

Out of the box comes a gorgeous ceramic bowl, handmade by an artist friend. On it, drawn in Koike’s hand, the Arabic calligraphy reads “salaam salaam”—“peace peace.”

“Japanese minister of defense, with Arabic calligraphy on china, and on the bowl saying ‘peace’. It’s something, right?”

Koike makes it a point to applaud Honda. “He is inventing some new horizons.”

About her own work, Koike says, “Because the brush is Chinese, the letters are Arabic, the ink is Japanese and I’m Japanese, it’s afusion of three cultures.”

Like her student colleagues, each shodo ‘arabi calligrapher brings two of the world’s great calligraphic cultures a bit closer.

|

Sheldon Chad (shelchad@gmail.com) is an award-winning screenwriter and journalist for print and radio. From his home in Montreal, he travels widely in the Middle East, West Africa, Russia and East Asia. |

|

Michael Yamashita (www.michaelyamashita.com) has photographed throughout East Asia for National Geographic for more than 25 years. Winner of numerous photography awards, he is the author of Marco Polo: A Photographer’s Journey (2004, Rizzoli). He lives in New Jersey. |