|

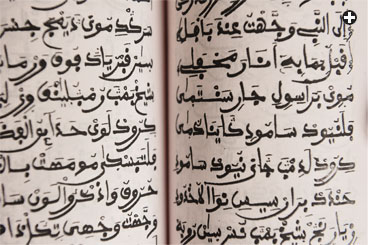

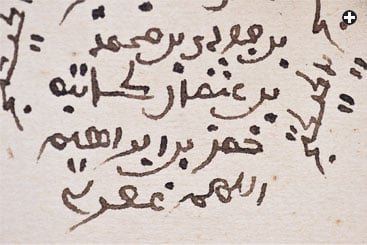

Above and below right: This page, describing constellations and calendars,

is written in Hausa, which is spoken by some 50 million people today.

|

“In the Hausa country, all chiefs of any position whatever have Arabic writers for conducting

their correspondence. ... Zaria at the present day is an exception. The ruler, Aliu dan Sidi,

has a personal preference for writing in the Hausa language, using Arabic characters, of course.

Hausa so written is locally called Ajami, an Arabic word meaning simply 'foreign.’”

— Frederick William Hugh Migeod, 1913

hen the 19th-century Senegalese religious leader

and patriot Amadou Bamba enjoined his followers to write tracts urging their countrymen to shrug off

French colonial rule, he encouraged them to use their native tongue: Wolof.*

When the Nigerian writer Nana Asma’u composed her elegiac portrait of the Prophet Muhammad in

the early 1800’s, she did so in what remains West Africa’s predominant language: Hausa.

And when the 18th-century court poet Sayyid Aidarusi honored his master with an adaptation of the

Arabic epic “Umm al-Qura,” he wrote in the prevailing tongue of some 50 million East Africans: Swahili.

While all three wrote in their native languages, the scripts they employed each bore a close resemblance

to Arabic. They were using Africanized versions of the Arabic alphabet, collectively called “Ajami.”

Much as the Latin-based alphabet is used to write many languages, including English, Ajami is not a language

itself, but the alphabetic script used to write a language: Arabicderived letters to write a non-Arabic—in this

case, African—language.

“Ajami” derives from the Arabic a'jamiy, which means “foreigner” or, more specifically, “non-Arab.” Historically,

Arabs used the word to refer to all things Persian or non-Arab, a usage they borrowed from the ancient Greeks.

Yet over the last few centuries, across Islamic Africa, “Ajami” came to mean an African language written in

Arabic script that was often adapted phonetically to facilitate local usages and pronunciations across the

continent, from the Ethiopian highlands in the east to the lush jungles of Sierra Leone in the west.

|

vernon doucette / boston university

|

|

Ajami adaptations of Arabic have parallels not only among Asian scripts, but also among European adaptations

of the Roman alphabet, observes Fallou Ngom. |

“If you go to the Kano Kurri market, in the heart of Kano city [in Nigeria], you will find thousands and thousands

of books written in Ajami. They are everywhere,” says Abdalla Uba Adamu, professor of science education and

curriculum studies at Kano’s Bayero University in northern Nigeria, home to the majority of the country’s Muslim

population. However, Adamu goes on to observe, many of the people reading those books are officially counted

as “illiterate” by the Nigerian government, which excludes Ajami from its public school curricula. Though research

has shown that as many as 80 percent of the estimated 50 million Hausa-speakers in Africa can read and write

Ajami, they are considered “illiterate” because, Adamu explains, in Nigeria and other West African nations, literacy

is equated with proficiency in Arabic or one of the Latin-alphabet-based colonial languages, usually French or

English. As a result, such surveys overlook tens of millions of Africans whose vernacular may be Hausa, Wolof,

Fulfulde or any of nearly two dozen other African languages. “This is a population that needs to be recognized,”

says Senegaleseborn Fallou Ngom, director of the African Language Program at Boston University’s African Studies

Center.

Ngom and Adamu are among those attempting to change this through a combination of activism, education and

scholarship. To them, it is galling that the Arabic alphabet was adapted over centuries for use in other parts of

the Muslim world, just as the Roman alphabet was adapted for use in, say, German and Turkish, yet Germans and

Turks who can read their respective adaptations are considered literate, whereas Africans who read and write Ajami

often fall below the official literacy radar.

For members of African societies where oral tradition

predominated, Arabic was the first written language to which

they had been exposed.

“The spread and development of Ajami is not, if you really look at it, different from the spread of Latin in Europe,”

says Ngom. Latin “was a church language, but its letters were adopted for use in French, German, Spanish, English

and other languages.”

Similar orthographic migrations and adaptations took place throughout the Muslim world. In Pakistan, for example,

the literary language Urdu is written in Perso-Arabic, a script adapted from Arabic in much the same way as Ajami.

In Malaysia, there is Jawi script; in Iran, Farsi; and up until the early years of the republic in Turkey, Ottoman.

In addition to a kind of literacy enfranchisement, Ngom and others also feel that a wider understanding and recognition

of Ajami could shed light on whole new chapters of African history, told from local points of view, which have yet to be

examined by scholars outside the region.

Reading in Ajami, “you will learn, for the first time, how people of West Africa perceived themselves in local accounts

of history, as opposed to colonial records,” Ngom suggests. Indeed, it has been his experience in his native Senegal

that colonial-era French and Ajami sources each paint distinct pictures.

“It is like you are looking at two very different accounts of the same events through different pairs of eyes,” he says.

“What the Ajami texts provide us with is access to what Muslims in West Africa hundreds of years ago were thinking

and saying in their own vernaculars, using their own idioms,” says Bruce Hall, assistant professor of history at Duke

University in Durham, North Carolina.

The story of Ajami is intertwined with the stories of how Islam came to Africa some 13 centuries ago and how

European colonization followed a millennium later.

Islam reached Africa first in Egypt, within a decade of the Prophet Muhammad’s death in 632 CE. By 750, it had

spread over North Africa and across the Mediterranean into the Iberian Peninsula and southern France.

By contrast, Islam came to sub-Saharan Africa more gradually, flowing south along the network of long-established

trade routes that tied littoral Mediterranean lands to the Niger Delta in the west and the ports of the Indian Ocean in

the east. Traversing these famed, trans-Saharan trade routes on the only creature suited to such a journey— the

camel—Muslim merchants came in search of gold, ivory, kola nuts and slaves to exchange for salt, copper and

textiles. In Arabic, they called the entire sub-Saharan region bilad alsudan, or “country of the blacks,” and the

trading cities where they conducted business became synonymous with exotica and riches: Gao, Djenné, Koumbi

Saleh and—the most fabled of all—Timbuktu.

But in addition to salt and silk, these merchants brought with them Arabic writing, language and ideas, most

prominently Islam’s message of unity through the worship of one God. The earliest urban center to embrace

Islam, late in the 10th century, was Gao on the Niger River in Mali. Other kingdoms along the serpentine

bends of the great river eventually followed: Takrur (Senegal); Songhay (Mali); Kanem-Bornu (Chad); and

Hausaland (Nigeria). By the 11th century, reports of these and other flourishing Islamic cities made their way

north to Al-Andalus in southern Spain, to the aristocratic geographer and historian Al-Bakri:

“The city of Ghana consists of two towns situated on a plain,” he wrote in his Kitab al-Masalik

wa al-Mamalik (Book of Highways and Kingdoms). “One of these towns, which is inhabited by

Muslims, is large and possesses twelve mosques in one of which they assemble for the Friday prayer.

There are salaried imams and muezzins, as well as jurists and scholars.”

These jurists and scholars, as well as the traders, turned out to be critical not only to the spread of Islam,

but also to the eventual development of Ajami.

From its beginning, Islam was a literate religion. Iqra’ (“read”) is the first word of God’s revelations to

Muhammad that became the Qur’an. Knowledge of Islam meant knowledge of the revealed word of God:

the Qur’an. Consequently, wherever Islam went, it established centers of learning, usually attached to

mosques, where children learned to read and write Arabic in much the same way that European and

American children have often been taught literacy by using the Bible. Thus, for the members of African societies

where oral tradition predominated, Arabic was the first written language to which they had been exposed.

|

|

|

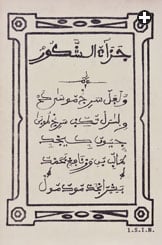

Twentieth-century poet Serigne Moussa Kah of Senegal wrote and published in Wolof. Like other Ajami scripts,

Wolof signals unique vowels and consonants by adding dots and other diacritical marks above and below nearly

equivalent Arabic letters. |

Yet while Arabic was the language of the Qur’an, as well as of the discourses and commentaries of

the several schools of Islamic law (shari’a), it could not meet every institutional and literary need

of the region’s powerful and politically complex empires. For example, when a 16th-century ruler

of the city-state of Kano signed his name, he could write his given name “Muhammad” in Arabic,

but he required a specially adapted script to render his Hausa surname, “Rufa.” Likewise, documents

pertaining to uniquely African cultural traditions, arts and sciences were also more easily written in

a script that could accommodate local vocabularies and pronunciations.

“In traditional medical books, for example, you will often find the text written in two layers of script, Arabic

and Ajami,” says Nikolay Dobronravin, African studies specialist and professor of world politics at the School

of International Relations at Russia’s St. Petersburg University. “The main text may be in Arabic, but you

usually have commentaries and the names of local plants and local medicines written in Ajami.”

The earliest surviving Ajami text is a tomb carving in Gao that dates from the 11th or 12th century. Paper

being more perishable than stone, the oldest Ajami manuscript dates to the 16th century: Written in Tamasheq,

the language of the largely nomadic Tuaregs, it is a pharmacopeia. Other early documents from the 17th and

18th centuries survive in Wolof, Fulfulde and Hausa.

To accommodate the vocabularies and pronunciations of each language, writers of Ajami modified the Arabic

alphabet, often creating new letters.

“Arabic has only three vowels, whereas Wolof has seven,” Ngom points out. “Similarly, there are consonants

in Wolof that do not exist in Arabic, so what the writers of Ajami did was to add dots above or below letters

that were their closest Arabic counterparts.”

Colonial administrators viewed Ajami as nonsense at best

and a threat to their authority at worst.

Collectively, all of these adaptations became known as Ajami—the scripts of African medical texts, botanical

surveys, works on the occult and astronomy, political, commercial and personal correspondence and religious

texts written well into the early 20th century. By this time, however, Ajami began running headlong into the

Latin-based scripts of European languages imposed by colonial administrators who viewed Ajami as nonsense

at best and a threat to their authority at worst.

“The French were very suspicious of this writing they couldn’t read,” says Jennifer Yanco, US director of the

West African Research Association. “A lot of libraries were burned. So the local people got wise, and they began

hiding books within double walls of their mud-brick houses, or they hid them in caves.”

In Nigeria, the British governor general from 1914 to 1919, Sir Frederick Lugard, directed that Ajami and

Arabic were both to be officially replaced by Hausa written in the Latin alphabet. This became known to

locals as bookoo (from the English word “book”). In the face of such cultural attacks, Ajami indeed became

precisely what the colonial governments feared: a tool of resistance and reform. Writing in Ajami in the

late 1940’s, Fulani poet Cerno Abdourahmane Bah grimly summarized the frustration of a browbeaten

population:

-

None of us was consulted about what we had to do.

-

They have been led as animals, exploited to satisfy every need, going up and down, without knowing the reason why!

Ajami also served those engaged in internal struggles. During the 17th century, a rising class of Islamic scholars

in Hausaland objected to those who professed Islam yet clung to animist beliefs and customs. By the early 19th

century, Shehu (Sheikh) Usuman dan Fodio, founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, emerged as the movement’s spiritual

and military leader. (His direct descendent, Sultan Muhammed Sa’adu Abubakar, remains the spiritual leader of

Nigeria’s 70 million Muslims.) A reluctant soldier, the Shehu preferred discourse and poetry as a means of persuasion.

Throughout his life, he composed numerous political and religious poems in Hausa and Fulfulde, all penned in Ajami.

“When we compose in Arabic, only the learned benefit,” he wrote. “When we compose it in Fulfulde, the unlettered also gain.”

|

|

|

This copy of poetry by the early 19th-century Nigerian leader Usuman dan Fodio is written in Fulfulde. “When we

compose in Arabic, only the learned benefit,” he wrote. “When we compose it in Fulfulde, the unlettered also gain.” |

Today, many of West Africa’s “unlettered” are still reading Ajami—on signs, in shops, in at least one weekly newspaper

(Nigeria’s Alfijir), as well as in locally published books that range from romance novels to religious texts.

Nevertheless, Ajami remains a kind of orphaned script, abandoned not only by secular authorities but also by conservative

religious ones.

“Starting in the 1700’s, the use of Ajami was not approved of by many West African Islamic scholars who associated

Arabic with Islam,” says Ngom. “They thought it would lead to the dissolution of the language of the Prophet Muhammad,

and so writers of Ajami had to defend their use of the script.”

Regrettably, says Adamu, the situation has not changed in some places. “In northern Nigeria it is considered

prohibited [by religious authorities] to use the Arabic script to write anything secular,” says Adamu, pointing out

that such is not the case in other Muslim countries. To change this in Nigeria, Adamu has been lobbying for what

he terms “the Ajamization of knowledge,” which would include the establishment of Ajami departments at universities,

the writing of classic Hausa literature into Ajami, the introduction of Ajami as a distinct subject in elementary

schools and the development of Ajami word-processing software. He would also like to see more official support,

as in neighboring Niger, where the government sponsors the publication of Ajami literature—and Ajami readers

are counted among the literate.

Meanwhile, Ngom last year co-authored Diving into the Ocean of Wolofal: First Workbook in Wolofal (Wolof Ajami),

the first book designed to teach students with no previous knowledge of the Arabic script how to read and write Wolof Ajami.

While such efforts are the first steps toward wider legitimacy, there remain other hurdles, such as the question

of the script’s standardization.

“Ajami is written in many African languages,” says Mahamane Laoualy Abdoulaye, visiting professor of linguistics

at Abdou Moumouni University in Niamey, Niger. “But even if you take just one, say Hausa, there are various

ways to transcribe it using Ajami. In order for it to work everywhere, there will need to be one system of how

to write it.”

These variations within Ajami-using languages underscore that Ajami scholarship requires multiple skills:

not only expertise in both Arabic and Ajami, but also in the particular local African language or languages in

which the Ajami texts are written.

Nevertheless, efforts to collect, preserve and publish the Ajami manuscripts that may help rewrite African history

continue to gain ground, and Ngom remains undismayed. He proudly associates the script with heritage.

“It is a badge of identity,” he declares, emphatically thumping his open palm against his heart.

“It is a way of saying, 'You see, I am Muslim, but I am an African Muslim.’”

|

Freelance journalist and author Tom Verde (writah@gmail.com)

is a frequent

contributor to Saudi Aramco World, and his article "Threads on

Canvas" (J/F 10) won a 2011 Clarion Award. He holds a master's degree in Islamic studies and

Christian–Muslim relations from Hartford Seminary in Connecticut. He has lived and traveled widely

in the Middle East. |

*This sentence is corrected from the print edition.