|

|

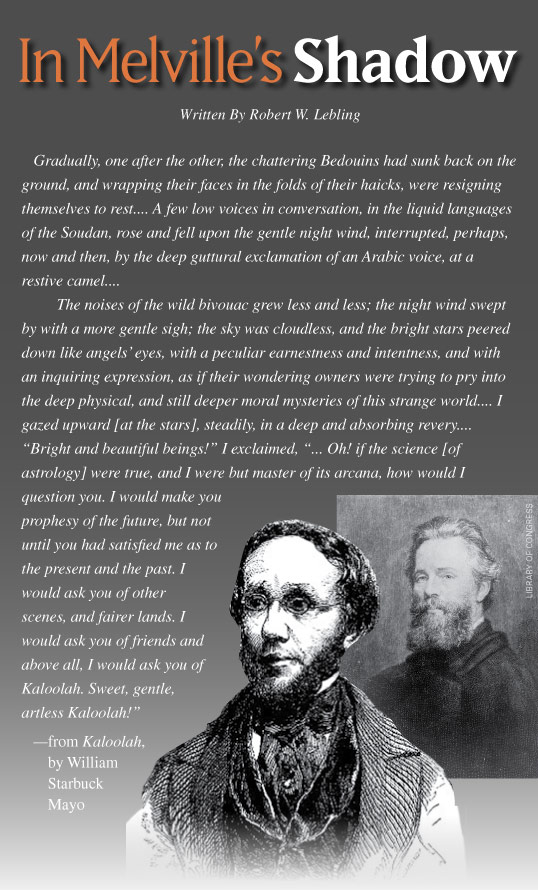

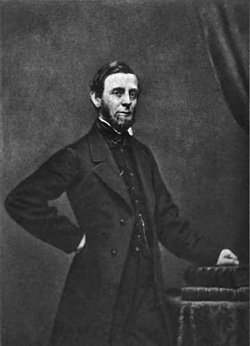

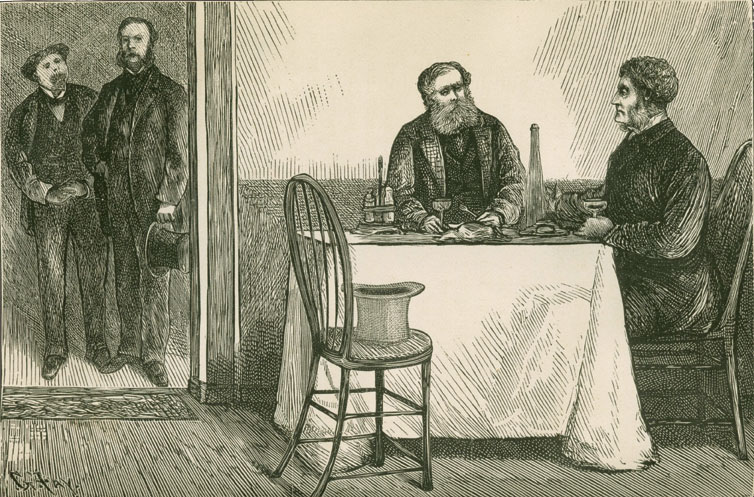

Based on a daguerreotype by Mathew Brady, who later

photographed the American Civil War, this portrait of William Starbuck Mayo, above, appeared

in the July 1, 1851 edition of The International Monthly Magazine of Literature, Art, and

Science. Above right: This anonymous etching of Herman Melville is based on a painting

by Joseph O. Eaton. |

uch were the reveries of shipwrecked American sailor Jonathan Romer, camped for the night with Bedouins

in the Sahara, as his thoughts turned to a remarkable princess from a lost African kingdom who would

come to have a permanent impact on his life. Yankee hero Romer was midway through his adventures

in Kaloolah; or, Journeyings to the Djébel Kumri, a novel that topped the best-seller lists in New York

and London in 1849.

uch were the reveries of shipwrecked American sailor Jonathan Romer, camped for the night with Bedouins

in the Sahara, as his thoughts turned to a remarkable princess from a lost African kingdom who would

come to have a permanent impact on his life. Yankee hero Romer was midway through his adventures

in Kaloolah; or, Journeyings to the Djébel Kumri, a novel that topped the best-seller lists in New York

and London in 1849.

Kaloolah was a forerunner of the “lost race” novels of H. Rider Haggard and others. It was a surprising

first effort—part adventure, part romance, part satire and 100-percent compelling. The book was written

in a fresh, direct, unself-conscious style, appealing to readers even today. Billed as the “autobiography

of Jonathan Romer,” the work was actually penned by a new literary sensation, William Starbuck Mayo,

whose star would burn bright and beautiful, like those high above Romer’s head in the trackless Sahara,

for a handful of years before being eclipsed forever by another New York novelist, the author of

Moby-Dick, Herman Melville.

But for a time, Mayo, a Manhattan physician whose writings were based on his own travels to Morocco

and the Sahara, was all the rage. Literary legend Washington Irving pronounced Kaloolah “one of the

most admirable pictures ever produced in this country.” Amid a flood of favorable notices, the prestigious

Democratic Review declared Mayo’s novel “decidedly the book of the season, having produced a sensation

quite as extended as did the works of Mr. Melville.” Kaloolah, it said, “has placed Dr. Mayo at once among

the most successful of American authors.” Everyone who was anyone in New York and London was

reading Kaloolah.

A year later, with the publication of his second novel, Mayo’s star rose even higher. Consider the scene

in New York on August 16, 1850: “Every where you go, you see people in cars and boat cabins in possession

of a couple of books in orange colored binding, as striking as the dress of a Turk would be in [a New York

political rally]; they are the bound pages of The Berber!”

Abraham Oakey Hall—lawyer, writer and future mayor of New York—made this observation in his journal

about Mayo’s The Berber; or, the Mountaineer of the Atlas: A Tale of Morocco, which was showing up

throughout Manhattan and at nearby vacation spots.

Today, Melville is considered an icon of American literature, and Mayo has disappeared in his shadow.

But it was not always so.

In 1850, when Herman Melville was hard at work on Moby-Dick, his writing career was on the skids. Following

the success of his first novel, the Polynesian romance Typee, and a respectable performance by its sequel,

Omoo, the great man appeared to have, at least for a time, lost his touch. Mardi, a more philosophical and

symbol-steeped novel also set in the South Pacific, had turned out to be a critical bust.

|

Melville was searching for his identity as a writer as he sought to distance himself from the Knickerbocker

style, a conservative, somewhat elitist literary approach by writers like Washington Irving that focused

largely on New York’s past and local traditions. The Knickerbocker writers were steeped in neoclassical

traditions of satire and wit, and admired the British leaders of the Romantic movement, such as Sir Walter

Scott, Lord Byron and Thomas Moore. To a Knickerbocker, writing essays, poems and novels was not the

stuff of a career but rather a leisure pursuit, a pastime for literate, well-educated aristocrats. Melville—like

fellow American writers Hawthorne, Emerson, Thoreau and Whitman—sought to introduce new direction and

creativity to his craft—a craft that post-Knickerbocker writers thought should be capable of providing a

worthy livelihood.

|

| Washington Irving called Mayo’s 1849 best-selling first novel “one of the most admirable ever produced in this country.” |

| |

It was ironic that Melville, the brilliant but struggling full-time novelist, should be upstaged by a new writer

who made his living as a doctor. Mayo’s success perhaps came from the fact that he did not seek to make

writing his career. His goal, as best we can judge, was simply to tell good stories. He wrote plainly, yet

vigorously and with humor, about things that were part of his experience. He wanted to share his experiences

at sea and abroad. Mayo had learned a great deal about the cultures and societies of “Barbary,” or North

Africa, and he looked for a way to convey this knowledge to American audiences. He started with short stories

and poems. Before long, he was writing novels.

Mayo was a native of Ogdensburg, a small port city in northern New York, on the St. Lawrence River across

from Canada. He was born on April 15, 1812, two months before the outbreak of the War of 1812, during

which British troops captured and briefly occupied Ogdensburg. Mayo’s father had been a captain in the merchant

marine, but had settled at Ogdensburg at the urging of his young wife, Elizabeth Starbuck, who was descended

from the whaling and merchant Starbucks of Nantucket, Massachusetts, a family quite familiar with the risks

and tragedies of the seafaring life. He set up a boatbuilding business primarily for the canal and lake trade

and helped to raise their four children, of whom William was the eldest.

William grew up in small-town circumstances similar to those of his first novel’s hero, Jonathan Romer.

He studied classics at the Academy at Potsdam, near Ogdensburg, and soon developed an interest in

medicine. After working for two local doctors, he went on to study in New York City, and after graduation

worked in city hospitals and private practice. Eventually poor eyesight and a yearning for adventure—characteristics

shared by Melville—led Mayo to set aside his promising career in medicine and begin charting plans to

explore central Africa. He never made it to the heart of Africa—then still a land unknown to Europeans—but

he traveled through Spain and North Africa’s “Barbary Coast,” and he ventured into the deserts of the Sahara.

|

Mayo returned to New York with stacks of notebooks crammed with local-color descriptions and accounts

of his adventures. He resumed his medical practice with renewed energy, but was consumed with a powerful

urge to write about North Africa and the Sahara, and the diverse peoples and customs he had encountered

there. In the early 1840’s, he began writing sketches, stories and poems—at first anonymously and then

under his own name—that captured the flavor of his overseas experiences. Among these Washington Irving

called Mayo’s 1849 best-selling first novel “one of the most admirable ever produced in this country.”

Today, it seems ironic that Melville, the brilliant but struggling novelist, should have been upstaged by a

well-traveled doctor. 18 Saudi Aramco World were “Don Sebastian: A Tale from the Chronicles of Portugal”

(September 1842) and “The Bereber” (November 1842) in the popular magazine Ladies’ Companion, and

“The Bedouin” (March 1844) and “The Captain’s Story” (June 1846) in The Democratic Review.

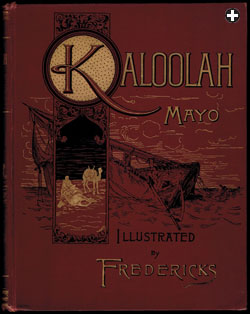

In 1849, Mayo brought a 750-page manuscript entitled Kaloolah to publisher George Palmer Putnam, at

155 Broadway. Putnam liked the novel, and he thought it would sell, given the public’s hunger for adventures

set in exotic locales, like Melville’s Typee. He edited the work down to about 500 pages. Mayo insisted that

his name not appear on the title page—perhaps he was uncertain how publication of the book would affect

his reputation as a prominent local physician. When the novel proved to be a hit, both commercially and

critically, Mayo agreed to have his name added to the title page of the second and subsequent

editions—as “editor” of Romer’s “autobiography.”

|

| COURTESY ROBERT W. LEBLING |

|

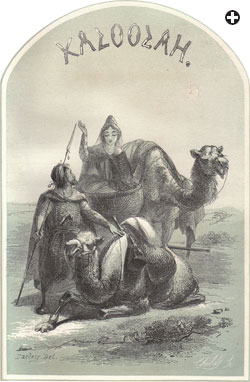

Mayo’s literary evocations were based not only on his romantic imagination, but also on his travels to Morocco.

These engravings, of Romer and Kaloolah with their camels in the Saharan desert, above, and a battle between

a lion and a serpent, below, both appeared in the fifth edition, printed in 1854. They were drawn by Felix

Octavius Carr Darley and engraved by Benjamin F. Childs.

|

Kaloolah was set in the American wilderness, on the high seas, in the Sahara and in the jungles of central

Africa, the fabled location of Jabal Kumri, or the Mountains of the Moon. In the 1840’s, the center of Africa

was still a land of mystery. It would be at least another decade before British adventurers John Hanning

Speke, Sir Richard Burton and others would open up the center of the continent and effectively remove it

from the exotic speculation of novelists. Mayo’s novel recounted the adventures of Romer, a quintessential

Yankee hero who survives shipwrecks, slavery and desert hardships to win the heart and hand of the

princess Kaloolah. He rescues her from slavery and returns her to the utopian kingdom of Framazugda, a

remarkable, progressive civilization built by Yemeni Arabs in the heart of the central African jungle.

Kaloolah is in a sense three books. The first part details Romer’s years as a

rambunctious, inquisitive youth in upper New York state. Aspects of Mayo’s own experiences

emerge at times from these tales. Romer engages in school pranks, hunts in the forests,

encounters American Indians, lives in a cavern in the woods, works for two local physicians

and illegally exhumes a body for medical research.

|

|

COURTESY ROBERT W. LEBLING

|

Romer’s adventures remind us of Mark Twain’s tales Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn,

written three to four decades later. We have no evidence that Twain (born Samuel Clemens) read Kaloolah,

but Mayo’s novel was published when Clemens was a young printer’s apprentice in Hannibal, Missouri, reading

voraciously every book he could get his hands on. It is highly unlikely that the young Clemens, who spent many

an evening after work at the Hannibal public library, would have passed up a best-selling adventure/romance

like Kaloolah.

|

|

WATTS PHILLIPS, COURTESY ROBERT W. LEBLING

|

|

After a string of adventures in deserts and jungles, Romer returns Kaloolah to her native

Framazugda, which Mayo portrays as a well-run, compassionate society—one from which New Yorkers

could take some lessons. |

In the second part of the novel, Romer goes to sea, primarily to avoid the legal repercussions of the

grave-robbing incident. He survives the capsizing of an American schooner off the Canaries, is forced

into service aboard a Spanish slave ship, escapes to an English brig and is shipwrecked again off the

western Sahara coast. Mayo’s graphic descriptions of the African slave trade, written barely a dozen

years before the American Civil War, include grim details of the practice of “loose-packing” versus

“tight-packing” slaves on the decks, and throwing overboard the sick and injured to certain death in

the open ocean. It is during Romer’s service with the slavers that he meets the princess Kaloolah and

her brother, who have been kidnapped and put up for sale in a coastal West African market.

In part three, Romer finds himself captured in the Sahara by a band of Arab Bedouins. He learns their

language and customs, and in time gains their trust, sharing some of his medical knowledge, marksmanship

and other skills. While traveling with the Bedouins, he once again encounters Kaloolah, still enslaved and

serving a family in a caravan. Romer and Kaloolah escape and head across the Sahara on camelback to

central Africa, where her mysterious kingdom awaits.

Framazugda, whose origin harks back perhaps to the traveling merchants of ancient Saba (land of the

queen of Sheba), is portrayed by the author as an advanced civilization—not a utopia, certainly, but a

wellrun, compassionate society from which mid-19th-century New Yorkers could take some lessons. Here

Mayo the doctor wields his satirical scalpel, advancing his personal interest in public health. Framazugda

is a clean society, which places a high priority on the health of its people. At the same time, its inhabitants

have a remarkably well-developed sense of smell and, in the words of Kaloolah herself, “could as well do

without food as without flowers.” Romer speculates that the stenches of New York and of other major

western metropolises are one reason why the citizens of such cities have never developed their olfactory

capabilities.

Some critics thought Mayo’s story had echoes of Melville’s Typee. But the author of Kaloolah

showed that his novel had been written before Typee was published. Mayo said in a preface

to the fourth edition: “It has frequently been the case among the numerous flattering notices, particularly

those from the English press, with which Kaloolah has been received, that allusions have been

made to the works of a distinguished American writer, and the suggestion thrown out that it was intended

to be of the class and character of Typee. The author himself can perceive no very close

resemblance in matter or manner; but whether there is a likeness or not, certain it is, that Kaloolah

was written before Typee issued from the press.”

|

|

In 1849, New York publisher George Palmer Putnam, above, printed four editions of Mayo’s novel.

Mayo, however, was uncertain of how it would be received by the public, and he allowed his own

name to be put on it only after it became a hit— and then only as “editor,” to better preserve the

illusion that the tale was protagonist Romer’s autobiography. |

While some have claimed similarities between the princess Kaloolah and Fayaway, the Marquesan

“island girl” of Typee, Kaloolah is the more developed character by far, voicing strong opinions and

taking decisive actions. By contrast, Fayaway remains a two-dimensional island beauty, seldom

depicted as a real person. Kaloolah, for example, even shows a determined environmentalist streak,

urging Romer not to allow his camel to crop the leaves of a thorny plant encountered in the dunes:

“No, no, do not harm it! ‘Tis but a mouthful, and existence must be sweet, or it could not cling to life

so bravely. Let it live on. Why should we be more cruel than the winds and sands of Sahara?”

Another distinction between the two tales is that Romer opts to marry Kaloolah and spend his life with

her in Framazugda, whereas Tommo, the protagonist of Typee, abandons Fayaway, leaving

her sobbing on the beach as he returns to “civilization.”

As far as we know, Melville never explicitly mentioned or commented on Mayo or Kaloolah.

But historian Cecil B. Eby, Jr., has made a case for the opposite of conventional wisdom: that it was Mayo

who influenced Melville, not the other way around. Eby argues that Melville could not have missed

reading the one novel to which his own writings were repeatedly compared in reviews of the day, and

that Moby-Dick may well have been influenced by certain themes developed in Kaloolah—for example,

Mayo’s portrayal of After a string of adventures in deserts and jungles, top and above, Romer returns

Kaloolah to her native Framazugda, which Mayo portrays as a well-run, compassionate society—one

from which New Yorkers could take some lessons. 20 Saudi Aramco World the Nantucketer as

adventurer, his description of whaling as ennobling, even “knightly,” and the concept of the whale as

a malignant intelligence.

There are a number of intriguing parallels between Kaloolah and Moby-Dick, along

with the obvious differences. When posing as a Bedouin in the Sahara, Romer calls himself Ishmael,

the name Melville later chooses for his whaler protagonist. It is also interesting, even if only a coincidence,

that Mayo’s middle name Starbuck is the name Melville selected for Captain Ahab’s first mate.

|

Kaloolah’s Romer traces his line of descent from the Coffins, Starbucks and other families

whose names figure importantly in the later Moby-Dick. Most of Romer’s relatives had spent their

sailing careers hunting “the ocean monster” from which alone “the highest honors” could be won.

One of his relatives had been “an officer of a ship which was struck and destroyed by an infuriated

cachelot, whether by accident or design remains a disputed point amongst whalers.” Perhaps even

more significantly, we can see a foretelling of Captain Ahab’s loss of his leg in the fate of another

relative of Romer’s, a boatsman hurled into the air by a collision with a pursued whale, who “fell into

the whale’s mouth, and the teeth of the animal closed upon his leg.”

“Both writers,” says Eby, “were competing for public favor by writing the same kind of fictional

narrative—the pseudo-autobiographical exotic romance—and Mayo’s spectacular popular success

must have been a bitter pill to Melville.”

Historian Perry Miller concludes in The Raven and the Whale, a highly regarded cultural

history of New York in the years 1833–57, that Melville read, and was disturbed by, Kaloolah.

During that period, Melville, Mayo and others were essentially warriors contending on the cultural

“battleground” on which modern American literature was defined. Miller reminds us that New York at

that time was not the premier literary center it later became, calling it “a literary butcher-shop.” In

those days, the Brahmins of Boston dominated American literature. In addition, the few great writers

of whom New York could boast—primarily Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper and transplanted

New Englander William Cullen Bryant—were difficult icons to challenge or supplant.

Mayo’s book passed through four editions between May and October of 1849. Kaloolah

appeared in the interval between the publication of Melville’s Mardi and Redburn,

covering roughly the same period, and Eby believes it probably “swam into Melville’s ken” at about that time.

Literature professor Gerald C. Van Dusen, who wrote a monograph on Mayo, believes Eby “overstates”

Mayo’s possible influence on Melville, failing to take into account “the rich body of folk tales and popular

adventure novels from which both Melville and Mayo were moving out in new directions.” In the 1830’s

particularly, there had been no shortage of popular maritime tales involving Yankee adventurers,

Nantucket whalers and monsters of the deep, and both novelists had certainly swum in those seas.

As Van Dusen points out, “It is easy to forget that fully one-third of Cooper’s novels—eleven, in

fact—were sea novels.”

Moby-Dick was published in 1851. Melville earned about $500 from the American edition of

the book, and the initial printing of 3000 copies was not sold out in his lifetime. Melville’s career began to

plummet in the mid-1850’s, and when he died in 1891, he was almost forgotten, just like Mayo.

Melville never achieved his goal of making a living as a novelist, later earning his bread as a customs

inspector for the City of New York. In his lifetime, he earned a total of just over $10,000 from his writing.

Fortunately for Melville’s reputation, a revival of interest in his work, first among scholars and then among

the public, occurred in the early 20th century. Moby-Dick is now regarded as his best work, and one of the

greatest American literary creations of all time.

In 1850, while Melville was hard at work on Moby-Dick, Mayo published his eagerly awaited second novel,

The Berber, a tale of 17th-century Morocco, which featured three interwoven love stories and

a number of sketches of the Berbers, the aboriginal inhabitants of North Africa. Once more drawing on his

own Moroccan experiences for context, Mayo writes about twin brothers separated as children, one of whom

is raised by Barbary pirates, and their reunion and adventures in the Atlas Mountains.

|

| courtesy robert w. lebling |

A year after Kaloolah, Mayo published The Berber, set in Morocco, but family affairs

and business kept him away from writing again until 1873, when he published Never

Again, a satire on the moneyed classes, of which he was part. It was illustrated with

engravings by Gaston Fey, including “Lunch at Delmonico’s,” below, which was

subtitled “Nothing but ghosts of ideas.” |

The novel received mixed reviews but sold very well. The American Whig Review thought

The Berber was probably better written than Kaloolah, but not as exciting,

not “a true romance.” The New York Evening Post was particularly pleased by Mayo’s

true-to-life descriptions of Berber society and customs: “His account of the Berbers ... is minute and

to the intelligent reader quite as interesting as the more narrative parts of the work. It is, perhaps,

the best evidence of the merit of the book, that the whole first edition was exhausted by orders from

the country before the first number had appeared in the city.” The Democratic Review was

also impressed by the ethnographic content of the book, and thought public interest in The Berber

would be “far superior” to even that of Kaloolah.

Publisher George Putnam felt that Mayo had legitimately staked his claim to Africa and should now

be working on a third novel set somewhere on that continent. But the doctor’s life took a different

turn. In the summer of 1851, he married a widowed New York heiress, Helen Stuyvesant Dudley,

a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of old New York (New Amsterdam). Mayo’s

marriage to a member of New York’s elite led to new social and financial responsibilities, not to

mention a substantial income from the Stuyvesant properties. He found himself involved in various

projects—mechanical inventions and business speculations—put forward by others in his new social

circle, even partnering with an Italian immigrant professor to petition Victor Emmanuel, king of Italy,

for rights to drill for oil in the Taro valley of northern Italy. They secured the concession, but

apparently never found a drop of petroleum.

In 1851, George Putnam reluctantly set aside his dream of a third “Africa novel” from Mayo and

published a collection of the doctor’s short and experimental fiction in a volume called

Romance Dust from the Historic Placer—an odd title suggestive of the California

gold rush of those times. Mayo described this collection, whose title he detested and sought to

change, as an effort “to keep afloat in the ocean of print until such time as a bark of more

pretension was ready to be launched.” That time did not come for many years.

In 1873, after more than two decades of literary silence, Mayo produced his final book, Never Again,

a satirical novel of manners about the moneyed classes of New York City. By this time, the author

had been virtually forgotten on both sides of the Atlantic, but the appearance of Never Again

returned him briefly to celebrity. Here, Mayo takes on the excesses of America’s financial elite, including

business speculators (of whom he had been one), while upholding the ideals of the American system.

Critics in the US, writing in times of escalating materialism at the outset of the “Gilded Age,” generally

treated the book harshly.

A reviewer in the Atlantic Monthly chastised Mayo for perpetrating “a false and vulgar libel on American

society.” By contrast, British assessments of the novel were exuberant. The London Athenaeum’s critic

compared Mayo to Charles Dickens, declaring, “In future we shall remember the name of Dr. Mayo as

that of one of the wittiest of modern writers, and greatest of living masters of human character.”

Never Again, according to Prof. Van Dusen, is “a partly serious, partly comic attempt to objectify

the New York to which Mayo had come as a young man, and now, after the Civil War, had found disturbingly

akin to a valley of ashes, made tolerable by the infinite possibilities of an intensely American dream.” Mayo’s

publisher, George Putnam, pronounced Never Again a “fair success” in commercial terms, but

Mayo was not sufficiently encouraged by its reception to continue writing professionally. He spent the next two

decades living in New York, apparently tucked comfortably into the same social and economic circles he

had lambasted in Never Again. He died in 1895, four years after the passing of Herman Melville.

|

When the Melville revival, sparked by US critic Carl Van Doren, gained widespread acceptance in the early 1920’s,

Mayo slipped even deeper into the shadows. Kaloolah was transformed from best-seller to literary

oddity. Scholars even began to forget what the novel was about. For instance, The Cambridge History of

English and American Literature (1907-21) transformed Framazugda, the fictional kingdom founded by

early Yemenis, into a “black Utopia” and summed up the book as a series of “wild adventures in Africa” spiced

with “a strange mixture of satire and romance.”

Unlike Melville, who aspired to join the august literary ranks of Irving, Cooper and Bryant, Mayo never

sought to be, or considered himself, a “great writer.” It is unlikely he will ever be accorded that distinction.

But at the same time, it seems unfair of some critics, such as Melville scholar Hershel Parker, to dismiss the

author of Kaloolah and The Berber as a mere “Melville imitator.” Mayo’s overriding

goal was to share with others the adventures and knowledge he had accumulated in his life, particularly in

his travels to Spain and North Africa. He was a first-rate storyteller who celebrated life and captured the

essence of his times. Perhaps, at the very least, he will be remembered for that.

|

Facsimile of a review of Kaloolah published in the leading political and literary periodical of the time, The Democratic Review. |

|

|

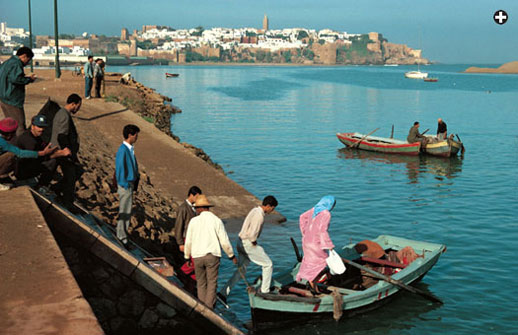

| CHRISTINE OSBORN / WORLD PICTURE LIBRARY / ALAMY |

| Adjacent to Rabat, capital of Morocco, the port of Salé in Mayo’s time was an infamous pirate base. |

n his preface to Kaloolah, “editor” William Starbuck Mayo explains how

the manuscript, purporting to be a young American’s account of his travels and adventures, came into his hands.

The stout roll of paper was filled with text written in English but with quaint, Tuareg-styled letters. A traveling

American merchant tells Mayo in a letter that he acquired the manuscript from a Jewish rabbi in Rabat, who in

turn received it from a “Moor of Tafilet,” or Tafilalt, a Saharan oasis in southeastern Morocco. The Moor

received the document from a “sick man” who had arrived in a recent caravan, with instructions that it be

passed to any western commercial agent.

In the merchant’s letter, we are told of a curious and comic incident that is almost certainly one of Mayo’s own

experiences during his travels in North Africa. It involves the legendary Salee Rovers, fierce pirates of the North

Atlantic. The Salee Rovers, who operated from the 17th to early 18th centuries, included in their numbers Muslim

Arabs and Berbers who had been expelled from Spain, as well as European renegades. From 1619-27, they

established an independent pirate republic at Sallee or Salee, now called Salé.

“You have heard of Salee, I suppose,” the merchant writes, “or rather, of the Salee Rovers, who not many years since

swept the Atlantic from Tercera to Teneriffe, and (with a degree of boldness that made them the bug-a-boos of crying

babies for miles inland) carried their bloody swallow-tail pendants up the English channel, and even through the

intricate passages of the Skagerrack and Cattegat.

“You have heard of these rascals, and of their town...; but perhaps you would have to refer to your geography,

or to a gazetteer; for in fact it is situated at the mouth of the Buregreb, exactly opposite the flourishing town of

Rabat, and precisely one hundred and twenty miles from the straits of Hercules, down the Atlantic coast of the

dominions of Muley Abderhamman.”

Salee is described as “a dilapidated town, whose inhabitants have nothing (spinning haicks and tanning

goat-skins excepted) to do but to nurse their prejudices and dream of the glorious days when a hundred

plunder-laden feluccas and polaccas crowded the now sand-choked harbor.”

With his pocket telescope, the merchant studied the walls of Salee: “The distance was so small that I

could see every stone of the towers, matchicolated with storks’ nests, and every crevice of the dilapidated

curtains connecting them. Was it fancy, or did the breeze really waft to my ears a faint echo of the million

sighs and groans, that years past, were borne upon every blast of the sea-breeze around those cruel walls?”

The merchant also noticed some long-legged wading birds—snipe—feeding along the beaches of the

Buregreb River, just beneath the walls of Salee. He decided to hunt a few for dinner, hiring a rowboat and

heading across the river.

“I expected sport, but I must say that I was wholly unprepared for such kind of sport,” he says. “It was

almost impossible to get a shot at them, they were so tame. No sooner would I succeed in raising a fellow

by poking him up with the muzzle of my gun, than, before I could draw trigger down he would pop right at

my feet, with an air as much as to say, wring my neck if you please, but don’t fire.”

Eventually, some birds took wing and he fired. “At the first shot all Salee was alive,” he says. A hundred

angry men emerged from the Salee water gate and began running toward him.

“Before they could reach me, I picked up my birds, stepped into the boat, and paddled back to Rabat.

When all was quiet, I ventured across again, took another shot, stirred up the old pirates’ nest, bagged

my bird, and made a similar retreat.”

He repeated this operation, fleeing each time from the former buccaneers of Salee, half a dozen times

in the course of the day.

His hunting adventures ended in disappointment when he learned that his “worthy Jewish host,”

Isaac Benshemole, was a strict constructionist of Judaic law and would not allow birds in his kitchen

that had been improperly slaughtered.

|

Robert W. Lebling (lebling@yahoo.com), former assistant editor of

Aramco World, is a staff writer and communication specialist for Saudi Aramco in Dhahran.

He is author of Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar

and co-author of Natural Remedies of Arabia.

|