|

|

philip scalia / alamy |

|

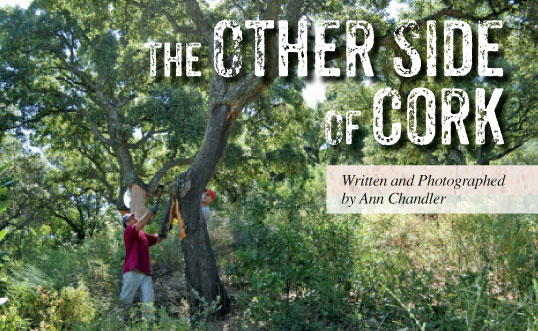

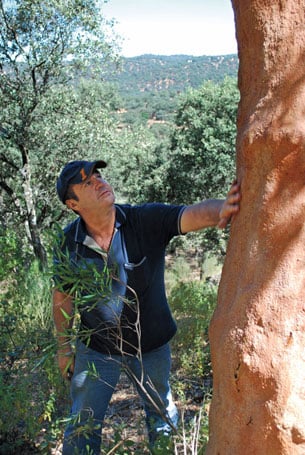

Top: In Portugal as in all seven of the Mediterranean countries where cork grows, harvesting it

remains a manual, traditional skill: Too much force on the axe can jeopardize regrowth of the

bark, while too little will fail to release it. Above: Cork harvesting is depicted on tiles in

Vila Viosa, Portugal.

|

The grin on Manuel Peixiubo's weathered face

appears easily beneath his frosty moustache. Peixiubo is jovial and friendly, but he works fast and

doesn't stop while he talks. Here on the Pipa cork farm near Coruche, 40 kilometers (25 mi) southeast of

Lisbon in Portugal's sunny Alentejo region, a man's wage is only as good as his speed. At 67, Peixiubo is

no amateur. His muscular arms have been swinging the traditional cork-harvesting axe since his 20's, and

he can tally over 20 arrobas a day. One arroba—the term, derived from Arabic, defined the

load that a donkey or mule could carry—equals 15 kilos, or 33 pounds, of cork bark. Peixiubo still

busies himself with construction work in the off-season.

Lumbering behind the men, a tractor pulls a wagon laden with the freshly harvested bark. High atop the load,

Gracinda Vicente balances herself while the wagon bumps through the forest. She laughs when asked her age.

At 59, her skin bears the evidence of years of outdoor work, gathering cork slabs from where the harvesters

drop them. Like Peixiubo, she began working the harvests in her 20's.

|

|

A good harvester will strip the tree in just a few large pieces.

|

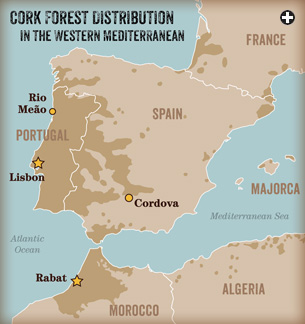

Peixiubo and Vicente are part of the approximately 6000 skilled seasonal workers in Portugal's cork industry,

which produces over 50 percent of the world's cork. The cork tree (Quercus suber) is an evergreen oak

found in seven Mediterranean countries: Portugal, Spain, Italy, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and France. The tree

thrives in areas with low rainfall, dry summers and high temperatures, its deep, extensive root system nourishing

it during drought. The bark is harvested every nine to 12 years in early summer, once the tree has reached 25

years of age and a circumference of 70 centimeters (27 1/2") at chest height. Cork trees can survive for more

than 200 years: The oldest known tree was planted in Portugal in 1783. Historical records dating back to the

fourth century bce document the use of cork in shoes, beehives, fishing gear,

boats and housing.

The laws that protect Portugal's 730,000 hectares (1.8 million acres) of cork trees date back to the year 1209,

a prescient regulation that allowed the forests to flourish and regenerate, maintaining a healthy biodiversity

that supports sport hunting as well as goat, sheep and cattle farming. One hundred percent renewable and recyclable,

cork is rapidly gaining in popularity as an environmentally sustainable product that can be used to make everything

from handbags, umbrellas, baseballs and car seats to expansion joints in dams and water reservoirs, and fuel tank

insulation on NASA space shuttles. Its remarkable properties that make it lightweight, impermeable to liquids and

gases, abrasion resistant, elastic, compressible, fire resistant, and an excellent thermal, acoustic and vibration

insulator are due to the 40 million gas-filled honeycomb cells contained in every cubic centimeter of cork.

When English scientist Robert Hooke viewed a

slice of cork beneath his microscope in 1665, he named the structures he saw cellulae—Latin for

"little rooms"—in the first recorded use of the biological term cell.

Harvesting cork is an acquired manual skill, the method unchanged for well over a century. Using a specially shaped

axe with a sharp, flared, round-cornered blade and a flat-tipped handle for prying off the bark, workers make rapid

horizontal and vertical cuts to free the bark in sections as large as possible. Each swing of the axe is carefully

controlled. Too much force will damage the delicate cambium layer beneath and jeopardize the growth of new bark. Too

gentle a swing and the bark will not release. When done properly, the bark pulls cleanly away from the tree with a loud crack.

Following the harvesters through the knee-high undergrowth, Conceição Santos Silva stops to point

out a rabbit burrow hidden in the wild lavender, noting that rabbits provide an important food source for the

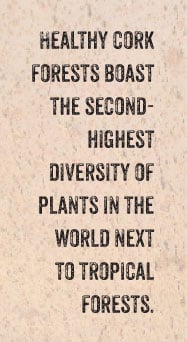

numerous birds of prey, like the endangered imperial eagle, that nest in the forest. Healthy cork forests, she

adds, also boast the second-highest plant diversity in the world, after tropical forests, and many of the plants

have aromatic, culinary and medicinal value.

|

|

armando franca / corbis |

|

Near Coruche, Portugal a truck delivers freshly harvested cork to a factory, where each

piece is first boiled, flattened and cleaned of the outer bark.

|

|

|

|

|

philip scalia / alamy |

|

Some items are cut or stamped from raw cork such as bottle stoppers while others are made by

grinding the cork, mixing it with adhesive, and molding, rolling or pressing it into an

ever-increasing number of lightweight, durable items all quite naturally waterproof.

|

"Our soil is very sandy and subject to erosion," she says, scooping up a handful and letting it sift through

her slender fingers. "If people stop using cork, this will turn into a desert." A busy mother of four and a

seasoned forest engineer, Silva is director of the Association of Forest Producers of Coruche. She knows the

cork forests like her own children.

The Pipa farm is one of many dotting the Alentejo region, which produces 72 percent of Portugal's cork. The

following day, Guilhermina Teixeira, a consultant with the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United

Nations, drives me to a collection of decaying white buildings 45 kilometers (28 mi) outside Lisbon. Once

a thriving company settlement, Rio Frio's cobwebbed stables still glow with early–20th-century

azulejo tile murals featuring images of Portugal's famous Lusitanian horses. Rio Frio also boasts

one of Portugal's few cork plantations, its trees planted in neat rows early in the 20th century.

In the forest, a playful competition is taking place between brothers harvesting opposing rows of trees,

their laughter and shouts ringing out in the hot air, interspersed with the crack of their axes. Sections

of bark fall to the forest floor in rapid succession. These workers, unlike Manuel Peixiubo, are paid a daily

rate by the buyer of the cork, but a harvester still prides himself on his speed. Familiarity with cork forests

like these is part of Teixeira's job, but she has a personal connection to Rio Frio. Teixeira's husband, Luis

Bruno Soares, is the architect behind its planned restoration. Soon the neglected village will become a thriving

ethno-tourist attraction, giving new life to the cork farm.

At the nearby Fabricor plant, his voice barely audible above the din of machinery, Nuno Marques explains how

the cork slabs are boiled twice for 40 to 60 minutes to soften them, clean out impurities and enhance the size

of the cells. "Every remnant from the cork processing is used," he says. "Nothing is wasted. Even the remaining

sawdust is burned to generate heat for the boiling process." After drying, the cork is ready for processing.

A two hours' train ride north of Lisbon, the small town of Rio Meão and the surrounding area are home

to 600 companies, many of which process Portuguese and imported cork destined to become household products.

"This whole area is dependent upon cork production," says Joaquim Lima, general manager of the Association of

Portuguese Cork Producers.

|

|

euforgen (2009) |

|

|

Public grazing rights in cork forests, once a generous policy, are now depriving cork

trees of essential forest-floor nutrients.

|

At the Granorte plant, product manager Paulo Rocha shows how granulated cork is mixed with a non-toxic

adhesive and molded into tiles or into large cylinders or blocks that are sliced thin, ultimately morphing

into a stunning array of decorative floor and wall coverings in a rainbow of colors and in varying shapes

and patterns. Some are the result of blending the cork with recycled leather or cement products.

At 3-D Cork, a small company run by father-and-daughter team Bernardo and Sara Nunes, granules are molded

into kitchenware, footwear, baseball cores, fishing equipment, tennis-racket handles and computer-tablet

covers. On the production floor, a woman assembles insoles for the boots of French soldiers. "Our sales

have increased by over 100 percent since we started the company five years ago," says Sara Nunes. "We run

our plant 24 hours a day to keep up with demand."

Further down the road, a grinning Americo Espirito Santo, general manager of Viking, a company that produces

and distributes hundreds of household and sports products made from cork, proudly dons a cork baseball cap

while showing off his latest line of yoga mats.

On a quaint cobbled Lisbon street, sales at a cork specialty shop have far exceeded the owners' expectations.

Inside Cork and Co., buyers from as far away as Russia and Dubai are tempted by everything from handbags,

briefcases, and jewelry to chairs and lampshades. Married lawyers Pedro and Christine Lucena opened the shop

one year ago, starting with a cork bracelet. "We wanted to feature a good quality Portuguese product," says

Pedro. The couple now has plans to expand internationally. Businesses like these form a growing part of

Portugal's economy—cork production that does not end up as bottle stoppers.

Faced with the threat of desertification as a result of climate change, Portugal's cork forests are closely

monitored to ensure their good health and continued replenishment through natural regeneration. One advantage

is that birds, animals and humans leave enough acorns on the ground to produce seedlings by natural means.

|

|

denita delemont / alamy |

|

|

Top: Harvested cork awaits processing near Mamora, Morocco the world's largest continuous cork forest.

Above: Soil scientist Hassan Benjelloun, at center, supports removal of acacia and eucalyptus

trees which "use up a lot of water"from cork forests.

|

In stark contrast, the Mamora forest near Rabat on Morocco's coastal plain—at 60,000 hectares (150,000

acres) the world's largest continuous cork forest—is not as fortunate. The sweet acorns here are highly

prized by locals as food, and the forest floor is threatened by over-grazing and dense human activity. During

the last half of the 20th century, the burgeoning population pushed the old system of registered grazing rights,

a remnant of French rule, into disuse. Compounding the problem, some local herders agreed to graze additional

animals belonging to outsiders in the forest. Without registration and monitoring, herd sizes outgrew the

forest's ability to support them and still maintain its own health. Unlike Spain and Portugal, whose cork

forests are mostly privately owned, Morocco's forests are the property of the state and thus accessible for public use.

Dr. Hassan Benjelloun, a professor of soil science at Morocco's National School of Forest Engineering,

accompanies me into the Mamora forest, a sandy area where cacti and doum (Chamaerops humilis)—

a shrubby palm with long, pointed leaves that the locals fashion into baskets and rope—grow amongst

the cork trees. Benjelloun points out some fenced off areas, an assisted regeneration project attempting to

save Mamora for the future. Local pastoralists are asked to avoid these areas for at least four years, an

economic blow that is softened by financial subsidies from non-governmental organizations. With the initial

intensive help of water trucks, soil cultivation and guards, regeneration of the forest has a fighting chance

in those areas. In other areas, eucalyptus and acacia trees, planted earlier as an economic move toward pulp

and paper production, are being replaced with cork seedlings. "Eucalyptus and acacia use a lot of water,"

says Benjelloun. "Their roots are shallow, while cork oak has roots that go very deep." Though he worries it

may be too little and too late, Benjelloun is hopeful that the regeneration project, which protects 1200 to

1400 hectares a year (3000–3500 acres), will be more than just a Band-Aid approach.

|

Dr. Abdellah Laouina, a tall, imposing man with a firm handshake, believes the project is an admirable effort,

but won't work on an expanded scale. "Mamora's future is very black," says Laouina, a geomorphologist in

Rabat who studies the experimental and social aspects of assisted regeneration for desire,

an international project to combat desertification. For Mamora to survive, he says, users must have a direct

interest in protecting it. He believes that a more economical approach, and one with a greater chance of

long-term success, would be a contract system between the state and the users of the forest that outlines

rights and duties.

While Mamora teeters on the brink, the smaller cork forests of Morocco's Rif and Atlas Mountain regions

are healthier. They manage some of their own natural regeneration, partly due to higher moisture levels,

difficult access and reduced human activity—the last because the acorns are bitter and unattractive as food.

In a sweltering storage yard in the Smento Forest District, ornate cobwebs decorate shoulder-high

stacks of cork from the 2010 harvest. In his office, forestry technician Djilali Said explains that the

unsold cork is the result of a tax recently imposed by segma, an independent

financial organization set up by the forest service to provide extra funding for forest management.

Morocco's 2011 harvest has also fallen victim: It's still on the trees. Ironically, Said chuckles, the lapse

in production might not be good for the economy, but it benefits the forests. Discussions are under way to

resolve the situation.

At the Center for Forestry Research in Rabat, physicist Dr. Abderrahim Famiri's research into new forms of

economic growth for Morocco's cork industry may have come just in time. Morocco is home to 15 percent of

the world's cork trees but produces less than five percent of the world's cork, of which 90 percent is

exported. Morocco has only 13 processing plants. Famiri would like to see all that change.

|

|

Near Cordova, Spain, cork farmer Francisco Calero inspects the trunk of a newly harvested tree.

|

He and his colleague Dr. Abdelaziz El Alami, a forestry engineer examining the stress impact of bark

removal, are passionate about saving the country's cork forests. Part of the problem, they believe, is

that cork in Morocco is a forestry resource, while in Spain and Portugal it is managed as agriculture.

"We have to change the way we think," says Alami, emphasizing his words with hand gestures. "We must

work hard to save the forest."

In southern Spain's Andalucia region, disciplined rows of olive trees and endless fields of golden

sunflowers blanket the fertile valley between the Sierra Morena and Sierra de Segura mountain ranges.

Spain produces nearly one third of the world's cork. Pulido Higueras, a forestry engineer, and Ana Carreo

Leyva, editor of El legado andalusi magazine, have brought me to the Finca Viuela estate near

the village of Adamuz. We are met by 47-year-old Francisco Calero, a stocky man with dark, bushy eyebrows

and a warm, piercing gaze. Calero, who harvested his first cork at 13, manages the farm he owns with his

two brothers.

Together we squeeze into Calero's truck and bounce across the vast acreage that his grandfather purchased

in the 1920's. Shifting the truck into four-wheel drive, Calero steers it into the hills, gaining altitude

until he stops in a forest of cork trees. After listening carefully for the ringing of axes that will

mark the location of the harvest workers he has come to collect, he takes his axe to a nearby tree, leaving

its trunk naked in less than five minutes. Despite the nearly 38-degree Celsius (100ºF) temperature,

the inside of the fallen bark is cool and moist to the touch, a testament to its insulating properties.

Apart from his mode of transportation and the cell phone on his hip, there is little to differentiate

Calero's work from his grandfather's.

|

|

jeronimo alba / alamy |

|

|

Top: In far southern Spain, tiles describe the 23-year-old cork-oak natural area.

Above: Near Mamora, Morocco, foresters hope these cork seedlings and thousands like

them will be ready for their first harvest around 2037.

|

Professor Miguel Angel Blanco Lopez, Calero's brother and an expert in tree diseases at the University

of Crdoba, points out spots on the dark green leaves. Fungus like this, he tells me, is the biggest

disease threat to the cork tree. It mainly affects the limbs, which can be pruned, he says, but if it

attacks the roots, the tree may die.

Higueras, an expert in human-animal balance in the forest, explains through our interpreter that

because fire risk in the Mediterranean region is high, forests like these must be cleared of encroaching

undergrowth every four to seven years to reduce the fuel available to a fire. Although cork bark is

resistant to flame, the oak's foliage is not.

In his office at the University of Lisbon, Dr. Miguel Bugalho, an expert on the conservation of

cork-oak woodlands with the World Wildlife Fund's Mediterranean Program, says that, in addition to

providing habitat for endangered plant and animal species, cork forests make a crucial contribution

to mitigating climate change. "The cork-oak woodland is a human-managed system," says Bugalho. "It has

a high degree of habitat heterogeneity, which is good for biodiversity. A well-managed system generates

biodiversity, long-term carbon storage and fire prevention services, which are all important not only

locally, but also globally."

|

It is cork's ecological qualities, versatility and sustainability that make it an attractive resource.

A feature exhibit last May in New York at the Museum of Modern Art's Design Week recently placed cork's

enormous potential in the international limelight, but consumer use of cork is nothing new. In Washington,

D.C., the cork floors in the Library of Congress have welcomed the feet of visitors for more than 100

years, and architect Frank Lloyd Wright chose cork when designing the famous Falling Waters home in

Pennsylvania in the 1960's.

With the combined efforts of scientists and farmers, cork will still be around for youngsters like Calero's

grand-nephew, Guillermo, a 7-year-old who followed us around the forest with notebook in hand, learning the

ways of cork management from his great-uncle.

"We have a saying," Conceição Silva says with a smile. "When we plant the cork tree, it

is not for our children. It is for our grandchildren."

|

Ann Chandler (www.annchandler.com) is a freelance writer and author living near Vancouver, B.C. She writes about science and anthropology for international magazines and has published two novels. |