t the international airport in St. Petersburg, Russia, a ticket checker waves me toward the

distant domestic airport for my flight to Simferopol, even though the Crimean city is in

independent Ukraine. "We always considered Crimea part of mother Russia," she explains.

"We still consider it our own."

Many books have been written about Russia's geopolitical interest in the strategic Black Sea

peninsula of Crimea, dating back to the times of Peter the Great. But it only takes one slim

volume of poetry to understand Crimea's hold on the Russian soul: Alexander Pushkin's 1824

"The Fountain of Bakhchisaray." It recounts a romantic legend set in the 500-year-old palace

of the Crimean khans—one of only three palaces of Islamic design surviving in Europe

today—and it is the source of a national love affair with the locale itself.

Pushkin is regarded as the founder of Russian literature and its greatest lyric poet. Among

his works, "The Fountain of Bakhchisaray" not only was one of his most popular poems, but also

served as a kind of Russian One Thousand and One Nights: a 3500-word verse that

recreates the world of the palace's builders, the vanished Crimean Khanate.

The tale's allure over these 200 years springs from the story: A love between a soulful conqueror

and a captive maid, doomed by a vengeful harem queen. So deeply does his poem resonate that

still today, moved largely by Pushkin, some 250,000 people a year come from all over Russia to

the palace, primarily to set eyes on the poem's set-piece—the actual Fountain of Tears,

which Pushkin turned into one of the most profound symbols of eternal love in all of literature.

But to today's descendants of the 800-year-old Crimean Tatar Khanate, Bakhchisaray

(pronounced bah-chih-sah-rye) means even more, says Yakub

Appazov, director of a local museum. The palace, he explains, "is the heart of the nation,

and all that belongs to the nation is Bakhchisaray." The nameplate on the palace, he adds,

reads "Bakhchisaray Palace of the Crimean Khanate" not only in Ukrainian and Russian, but i

n Crimean Tatar as well.

Since ancient times, successive civilizations in Crimea have tended to erase the traces of

their predecessors. This was nearly the fate of both fountain and palace. But they endure

because the story of "The Fountain of Tears" moved not only the Russian people, but also

czars, a great empress and the First General Secretary of the Communist Party. If not for

Pushkin's poem, the palace would have been lost.

But now let's find it.

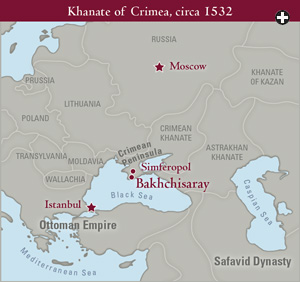

rom the 16th to the late 18th centuries, the town of Bakhchisaray, whose name means "the

palace in the garden," was the capital of the Crimean Khanate, the state that in 1438

broke away from the Golden Horde, the alliance of Mongol and Turkish tribes whose empire

reached from the Pacific to the Volga River. The Khanate, extending east from the Black

Sea to the Caspian-Volga region, was a formidable power, and its line of kings descended

from Genghis Khan himself. The founder of the dynasty, Menli i

Giray, took the imperial title "Sovereign of Two Continents and Khan of Khans of Two Seas."

Over some 250 years, from 1532 until 1783, the palace at Bakhchisaray was the residence of

48 khans of the Giray dynasty, and the sumptuous complex lived up to its name, with gardens

and a life-giving, sustaining and purifying supply of water as the focal point of its design.

|

|

http://atlas.7jigen.net/en/historical/crimean_khanate |

But now it's been 235 years since the khans were masters at Bakhchisaray. Over these years,

the palace has taken on a Russianized, "Asian Baroque" appearance—"greatly distorted

compared to its initial look," admits the palace's former assistant director Oleksa Haiworonski,

a devotee of Crimean Tatar history. More-over, due to a Russian attack in 1736 that destroyed

the palace's archives, the palace lacks any ethnographic information on the everyday life of

the khans and other inhabitants there, as well as any documents from the period, says Haiworonski.

All of which suits Bakhchisaray better to legend and poetry than history.

Luxuriance to this day enthralls

Those vacant pleasances and halls

Where now the Khans? The Harem where?

All now was silent, all was dreary,

All had been altered but not there

Was what bestirred the spirit's query....

Inside, the L-shaped Fountain Court's cement walls are barren. Its uneven floors have been

smoothed by millions of steps over the centuries. It's shaded and cool, dappled with sunlight

from the open door to the harem garden.

The Fountain of Tears itself is tucked into a corner, with a bust of Pushkin alongside.

From its grey marble and floral arabesques, a sequence of nine basins descends.

"Poetically described to me as la fontaine des larmes [the fountain of tears], I

saw a broken fountain; from a rusty iron pipe water dripped drop by drop," wrote Pushkin to

a friend after first seeing the fountain on his visit in 1820. But later, he saw the glint

of poetic gold in the image of the fountain as a desolate eye, weeping endlessly. From 1821

to 1823, he worked on his poem, which was published in March 1824. It became his best-selling

poem. Soon afterward, in 1826, he published a shorter, reflexive verse titled "To the Palace

of the Fountain of Bakhchisaray."

Frankly, Pushkin's prosaic, even shabby, first impression in 1820 is still accurate. American

traveler Matt Brown reacted to his first sight of the fountain: "Before I walked in, I read

Lonely Planet where it described the weeping fountain. You expect to walk into the

place and see such a fabulous structure, and it was so disappointing."

But Russians disagree: Read Pushkin's poetic rendering, and your reaction may be like those

unending lines of tourists who approach the humble-looking fountain with solemnity, open-mouthed

curiosity and visible emotion. With trembling hands, a few put in place two white roses,

mimicking Pushkin's hauntingly beautiful gesture from his second poem:

The stream of love, the stream alive,

I brought to thee two roses, as a present.

I like the ceaseless murmur thy,

And lyric tears, still and pleasant.

Ludmila Nosoyan is a Moscow fashion designer who tries to visit the fountain once or even twice

a year. She remembers first hearing Pushkin in early childhood. "It's a story from the magical

world that has nothing to do with the reality of the Orenburg steppe [in Siberia]. Magical people,

strange and beautiful clothes—a dreamy story."

She acknowledges, barely, that the fountain itself is so modest. "While the reality is not so

striking, it still keeps that dream intact," she says. "Here, I'm enchanted in a different time.

I see the fountain, I see Zarema, Maria, and Giray. It's an unfading love story."

In the story Pushkin tells, the palace was home, long ago, to an "imperious lord of nations,"

a khan whom Pushkin names simply Giray. In the inner court was the harem, where only Giray was

permitted entrance. There, Zarema was "the harem's queen, love's brightest star"—until the

arrival of Maria, an "orphaned princess snatched by arms" from a castle in Poland. ("She was her

greybeard father's pride / Joy of his years' receding tide.") Giray secretly falls in love with

the beautiful Maria, but his love is unrequited. She is shy, alone, distraught by captivity, and

chaste. She desperately resists him and "in this spare lodgement set apart / From envious wives,

she grieves her heart." But that doesn't stop envious Zarema, who steals into Maria's room and

murders her. Giray witnesses the crime, and he casts Zarema out. That night she, too, dies. Giray,

grief-stricken by his losses ("Then whisper something and it seems / Tears scored his cheeks in

scalding streams") and ennobled by romantic love, gives orders to his sculptor:

Back home the Tatar chieftain came;

A marble fountain he erected

To honor poor Maria's name

Deep in a corner of the Court....

There's writing, too; the probing whirls

Of time have not erased it yet.

Behind its curious curves and curls

Within the stone the waters fret

Then gush and rain in tearlike pearls,

Undried, unsilenced evermore.

Thus mothers mourn in grief unmeasured

Sons done to death by savage war.

This tale of woe from ancient lore

The maidens hereabouts have treasured;

Each age the mournful mark reveres,

And knows it as The Fount of Tears.

What people today see in the fountain, says Emil Ametov, a young palace assistant historian,

are teardrops from a human eye, filling first the large basin, a "broken heart," and then spilling

over into the pairs of smaller basins, thus offering the relief that comes with tears—but

then, as memories rise up again, the pool of tears refills and the heart repeats the cycle again a

nd again in inconsolable grief and continuous love.

folk tale," says Haiworonski about Pushkin's epic poem. "Actually, we don't know how factual this

story is of Dilara Bikech, the noblewoman whom the Khan fell in love with. We know nothing about her."

Most historians believe that the original location of the Fountain of Tears was a niche in an

octagonal mausoleum built on a hill above the palace by Khan Qirim Giray in 1764. On the mausoleum

was inscribed only a woman's name: Dilara Bikech.

Haiworonski, a Polish-Ukrainian who grew up in Bakhchisaray, finishes his third pour of tea into

a small porcelain bowl, in the Crimean Tatar style. "No evidence, just speculation: Even a khan's

love could not be the basis for burying a woman in a mausoleum as if she were a saint," he says.

"We can find much more substantial reasons for that, because we know Dilara Bikech as a donor of

mosques in the town. One of the mosques in Bakhchisaray, the so-called Green Mosque, was inscribed

with her name. We know the tradition of rich women building mosques did exist in the Crimean court.

So perhaps it was not the khan's love that was the reason to bury her with such a special honor.

Unfortunately, for now, we do not have any documents that would help us discover who she was."

In 1238, the grandson of Genghis Khan, Batu, led an alliance of Mongol and Turkish tribes

to conquer an empire that stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Volga River. Because of

its wealth and power, this khanate came to be known as the Golden Horde. The kingdom of the

Qipchak Khans, descended from one of the oldest Mongolian or Tatar races, formed a regional

capital in Qirim—the name from which today's "Crimea" is derived—and the people

who called themselves Qirimtatar embraced Islam in the 13th century.

After the defeat of the Golden Horde in 1441 by Tamerlane, Crimean nobles fell away from Qipchak

to form the independent Crimean Khanate under Haci i Giray, thus

introducing the name of Giray into the dynasty that followed. In 1475, Haci i

Giray's son Meñli i Giray was taken prisoner by the Genoese,

who sent him to Istanbul, where Sultan Mehmet ii forced him to recognize

Ottoman control over his Crimean Khanate.

He was then permitted to return to his throne, and in 1502, he fought the Golden Horde's last khan

to defeat at the Dneiper River. His sons went on to defeat the Russians near Moscow, and they forced

the Russians to pay tribute to the khanate, a submission that continued until the end of the 17th century.

It was the Cossacks who, in the late 18th century, began to push back the khanate and the Ottomans.

In 1774, the Crimean Khans fell under Russian influence, and by 1783, Crimea was annexed into Russia.

It was part of Russia, then part of the ussr, then part of the Ukrainian

Soviet Socialist Republic, and was briefly autonomous. In 1992, newly independent Ukraine took

possession, and today it's officially the Autonomous Republic of Crimea of Ukraine.

Visiting Bakhchisaray at about the same time as Pushkin, the traveler Muraviev-Apostol wrote of the mausoleum,

which still stands, "Very strange that all the people here vouch that this beauty was not a Georgian but a Polish girl,

allegedly kidnapped by Qirim Giray. However much I argued with them, no matter how I assured them that the

traditional story has no historical basis, and that in the second half of the eighteenth century it was not so

easy for Tatars to kidnap a Pole, all my arguments were useless. They maintain as one: The beauty was Maria Potocka."

There may indeed have been a historical Maria Potocka, a Polish noblewoman who had been kidnapped on a Crimean

Tatar raid and held in the khan's harem, and who ultimately became his wife. But the timing is off: The tale

is first mentioned in the writings of Crimean historian Sayyid Muhammad Riza. In his account, it was Khan

Fetih ii Giray (ruled 1736–1737) who was given the captured maiden—

and who restored her to her family in exchange for a ransom in gold. Since the fountain was built in 1764, the a

ccepted historical wisdom is that it actually commemorates Dilara Bikech, who was likely a Georgian girl who

died young, for dilara is a Turkish word meaning "beloved," and bikech was a name usually

given to concubines.

Adding to the legend, just 20 years after the fountain was erected and after the death of the "last khan"

who built it, the empress of Russia, Catherine the Great, came calling at Bakhchisaray. The accounts of her

visit in 1787, and her own words, show that even then the palace already had a claim on the Russian romantic

imagination.

Bakhchisaray was the last stop on Catherine's eight-month victory tour celebrating her defeat of the Ottoman

Empire in the Russo-Turkish war, which had ended in 1774, and the Russian annexation of Crimea in 1783. It must

have been a sight to behold: 12,000 horsemen of the Tatar cavalry, richly clothed and armed, escorted Catherine,

the guard of honor and her retinue of 2300 to the palace of the former khans.

Mastermind of the visit was Prince Grigori Potemkin, Russia's most powerful statesman and Catherine's intimate,

who had given orders for the khan's palace to be completely restored and refurbished, with the ultimate goal of

making it into his own "Russian Alhambra."

He succeeded in impressing Catherine. From Bakhchisaray, the empress wrote these words to Potemkin, as

translated by Andreas Schnle:

I lay one evening in the Khan's summer-house,

In the midst of Muslims and the Islamic faith.

In front of this summer-house a mosque was built,

Where five times a day the Imam calls the people.

I thought of sleeping, but as soon as I closed my eyes,

He shut his ears and roared with all his might...

O, godly miracles! Who among my ancestors

Slept peacefully from the hordes and their khans?

But what prevents me from sleeping in Bakhchisaray

Are tobacco smoke and this roar. Is this not the place of paradise?

One of history's great romantics, Catherine stayed three days in Bakhchisaray. As part of his coup de

théâtre, Potemkin had moved the fountain that Pushkin would immortalize 37 years later

from its original location in the mausoleum to its present location, in an inner courtyard, so as to put it near

the empress's apartment, certain that she would appreciate what was then already local folklore: the tale of the

khan, the harem queen and the captive maiden. One can imagine Catherine and her suite whiling away the evening with

their guests, listening for the fountain's teardrops falling. The echoes are long in that courtyard.

ne late afternoon at the palace, I met Amit Refetov and his bride, Elmaz, who had come with members of their

family to the Great Khan Mosque in the palace for a blessing on their marriage. "It's our Crimean Tatar mosque,"

Refetov said. "Even the walls can bless the new family."

Many of those walls, however, except in the oldest and best-preserved part of the palace, have long since been

altered. When Pushkin came here in 1820, he told about "walking around the palace greatly irritated by the neglect

in which it is decaying, and by the half-European alterations to some of the rooms."

He could blame Potemkin, in part, who had enlisted the services of the architect Joseph de Ribas, who was not

well acquainted with Islamic styles or principles, to refurbish the palace. They wanted to please the empress

with beautiful mansions that catered to European and imperial expectations, so they mixed Asian and European

styles—not always with success.

Pushkin's romantic tale opened the door for another romance, this one between Crimean Tatars returning, in

recent decades, from Soviet exile and the palace itself, which they regard as a precious icon of their

culture. Sajyar Ablyaev, 55, is "brigadier" of the 12-man crew that maintains Bakhchisaray Palace. He

takes me by the hand to show me that, just outside the walls, there is another fountain, built in 1747

by Khan Selim ii Giray. Ablyaev tells me how the art and science of the

khanate's hydraulic engineers is still a marvel today. Small ceramic pipes, boxed in an underground stone

tunnel, stretch back to the spring source more than 200 meters (650') away.

As he shows me, children—some three generations removed from those who were exiled—and a few of

their elders come up to greet Ablyaev warmly. Like the Fountain of Tears, this fountain too seems not much

to look at at first. Ablyaev steps down and turns on the tap. Water flows out with surprising pressure, clean

and pure from the source. He turns it off, and then back on. Everybody giggles and laughs and jokes in Crimean

Tatar—a living language once again. It is as if this running stream is irrigating the Crimean Tatar

attachment to a palace that now, 250 years later, feels very much their own. The smiles around this humble

spring seem enough to gladden the heart of any Giray khan. In its own way, it is another kind of poetic justice.

Further changes to the palace usually coincided with the visit of the next czar or czarina. This came to mean

demolition, too: In the 1820's alone, several buildings of the harem, the Winter Palace, a large bath complex and

other parts of the palace were destroyed. Over the decades, the palace was reduced from an area of 18 hectares to

four—from 44 acres to 10.

Pushkin's influence, however, was immediate and—architecturally, at least—favorable. While "The Fountain

of Bakhchisaray" helped promote a popular, romanticized picture of the Islamic world, the changes made to the fabric

of the original palace began to elicit protests from architects, artists and even czars.

Within a year after Pushkin's visit, a parade of writers came to the palace, and some even reprised the drama.

Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz is now renowned for his Crimean Sonnets, one of which speaks of Bakhchisaray,

translated here by Dorothea Prall Radin:

A vessel hewn from marble stands untouched

Within the hall the harem's fountain-spring;

Seeping pearl-tears, it sobs across the waste,

"Love, glory, potentate! where are you now?

You claimed eternity,

spring-water's fleet.

You have fled; infamy! the spring runs on.

There were many others: Alexsander Griboyedov, Aleksey Tolstoy, Ivan Bunin, Sasha Cherny, Ukraine's Mykhailo

Kotsyubynsky and dozens more. Artists came too: Russian romantic Karl Bryullov worked on a painting for 12 years,

an orientalist, idyll-in-a-harem canvas titled "The Fountain of Tears." Like Pushkin's poem, every Russian knows it.

On the screen, the great filmmaker Yakov Protazanov made his first feature film in 1907, which he titled "The

Bakhchisaray Fountain."

But it was a ballet based on Pushkin's poem that did the most to save the palace from destruction.

In 1944, during World War ii, the Soviets deported Crimean Tatars en masse to territories

in what is now Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia, in retaliation for the collaboration of some Tatars with Nazi

Germany. Forty percent of the deportees died within two years.

This ethnic cleansing was followed by a cultural one, as historical and linguistic traces of the Crimean Tatar people

on the peninsula were expunged. Crimean Tatar and Turkic place names of villages, towns and cities were Sovietized. Cemeteries

and mosques were destroyed. The Soviets proposed to rename Bakhchisaray palace "Pushkinsk" ("Pushkin") or "Sadovsk" ("Garden").

According to the director of the palace's museum during those post-war years, Maria Yustara, who was in Moscow at the time,

there were plans to raze the palace as well.

Fortunately, Boris Asafyev's ballet "The Bakhchisaray Fountain" happened to have been first performed on stage

some 10 years earlier, and it had toured all the major Soviet cities to great popular acclaim. Most importantly,

one of its fans was none other than Soviet leader Joseph Stalin—indeed, it was his favorite ballet. Pushkin

too was beyond Soviet reproach, having been claimed "entirely our own, a Soviet" in the Communist Party's official

newspaper Pravda on the centennial of the poet's death in 1937.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that the poet Pushkin's imagination gave not only life but also, ultimately,

sanctuary to the fountain and palace, whose name remained unchanged, and whose buildings endured the Soviet era intact.

Today, the khans' palace, with its mosques, cemeteries and other buildings, is the only major remaining monument

of the Tatar visual arts of the Crimean Khanate. As Haiworonski puts it, "the palace still remembers its past, that

once it was a paradise." But if you go, know your history. And bring your Pushkin.

O magic shore! O visions' balm

All there inspirits: peak and pine,

The graceful valleys' sheltering calm,

The rose and amber of the vine,

Cool brooks and toplar shade nearby...

Inscribed in gold above the Fountain of Tears is a verse of Surah 76 of the Qur'an, which names, among

the benefits the righteous will enjoy, "A spring [or fountain] there, called Salsabil." According to

exegetist Abdullah Yusuf Ali, the name literally means "seek the way." It refers to a particular spring

in heaven, and it also contains allusions to such concepts as "nectar," "smooth" and "easy on the throat."

The Arabic word sabil commonly refers to public fountains erected as pious acts to provide

water for wayfarers.

The tradition of designing fountains called salsabil is well established in Islamic architecture,

especially in Iraq and Syria, and began around the Black Sea in the 12th and 13th centuries. These were not

simple fountains. Rather, a salsabil often involved several basins, and sometimes channels that distributed

water through basins and pools. According to scholar Yasser Tabbaa, salsabils were notable esthetically for

the "alternating stillness and movement of water, the temporarily solid or sculptural appearance of water

[and] the use of water as a thin veil over stone."

At the Fountain of Tears, water flows into the upper middle bowl, out to a pair of side bowls, then back

into a center basin, and repeats this pattern three times.

At the top of the Bakhchisaray salsabil are eight other verses. These are secular, praising Khan Qirim Giray,

who in 1764 commissioned the Persian master Omer to construct the fountain.

The Editors thank Mohammad S. AbuMakarem for his research

|

Sheldon Chad (shelchad@gmail.com) is an award-winning screenwriter and journalist for print and radio. From his home in Montreal, he travels widely in the Middle East, West Africa, Russia and East Asia. In October, he was a featured speaker at the Dialogue of Civilizations in Rhodes. |

|

Photojournalist Sergey Maximishin (maximishin@yandex.ru) is a native of Crimea. He has been recognized regularly since 2001 by both the Russia Press Photo Contest and World Press Photo. He is a former staff photographer for Izvestia, and his work appears frequently in leading world magazines. |