|

| NEW YORK pubLIC LIbRARY |

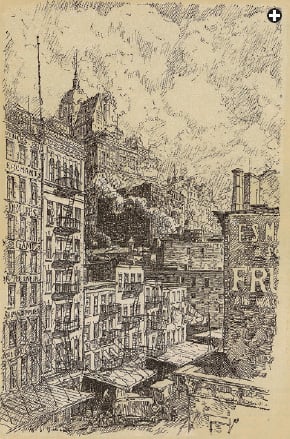

| Little Syria lay three blocks south of Washington Market, the city’s largest wholesale food market, depicted in this 1916 illustration from Harper's magazine. |

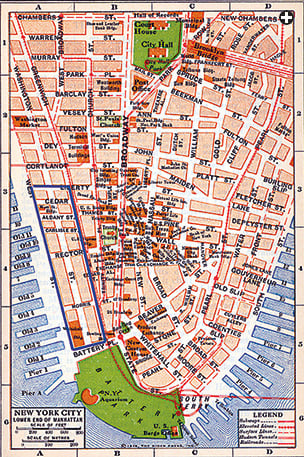

ON NEW YORK’S MANHATTAN ISLAND—an American Indian name meaning “many hills”—on lower Washington Street—named for the first us president—once lived people with Arab names like Sakakini, Khoury and Hawawiny. The great majority of them were Christian immigrants from the lands known today as Lebanon and Syria. They began arriving in the 1870’s from what was then the Ottoman province of Syria, most leaving behind home villages set in mountains much higher than Manhattan’s not-so-hilly terrain.

he émigrés brought their foods, clothes and traditions—including street peddling—with them. Their neighborhood became known as Little Syria, and for some 75 years, until just after World War ii, it was the point—within sight of the Statue of Liberty—where many Arab immigrants arrived in the United States.

he émigrés brought their foods, clothes and traditions—including street peddling—with them. Their neighborhood became known as Little Syria, and for some 75 years, until just after World War ii, it was the point—within sight of the Statue of Liberty—where many Arab immigrants arrived in the United States.

Like America itself, Washington Street changed over time. In the late 1940’s, the construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel tore through streets to the south, dispersing what was left of a dwindling Arab population and closing the neighborhood’s last two Arab restaurants, The Nile and The Sheikh. As Lower Manhattan became a place of elevator-equipped buildings with offices of high finance, so small shops and warehouses closed. Tenements were torn down. A parking garage—the most hurtful affront to a community that once made its living by ambulatory sales—was built.

|

RANSOM CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS (DETAIL COURTESY

ARAB AMERICAN NATIONAL MUSEUM) |

Then came the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, just a few blocks to the north.

Today there is a newfound awareness of the neighborhood’s role in Arab–American history. Descendants of the immigrants whose origin gave the area its name have raised the alarm about losing what is left of its original architecture. A conference on Little Syria at the Museum of the City of New York in 2002 resulted in publication of the book A Community of Many Worlds: Arab Americans in New York City. The Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, is planning its own Little Syria exhibition. And, as the most literal symbol of this historical rediscovery, the cornerstone of St. Joseph’s Maronite Church—which began serving the neighborhood in the 1890’s—was found in the rubble of the World Trade Center.

|

| Library of Congress |

| Top: From Liberty Street south to Battery Place, Washington Street offered Arab immigrants simple lodging and, in this restaurant, above, a taste of home. |

The initial impetus for the first wave of Arab immigration to New York was America’s 1876 Centennial Exposition, held in Philadelphia. It drew a number of Arab delegates, and they returned home extolling the new opportunities in the us. In 1890, the Bureau of Immigration hired one Najib Arbeely to help steer his Lebanese countrymen from the immigrant intake centers, New York’s Castle Garden and later Ellis Island. As Abraham Rihbany succinctly put it in A Far Journey, a memoir of his arrival in 1891, “We landed at Battery Place [Manhattan’s southernmost point], explored the dock for our trunks… and proceeded to a lodging house on Washington Street.”

|

| Library of Congress |

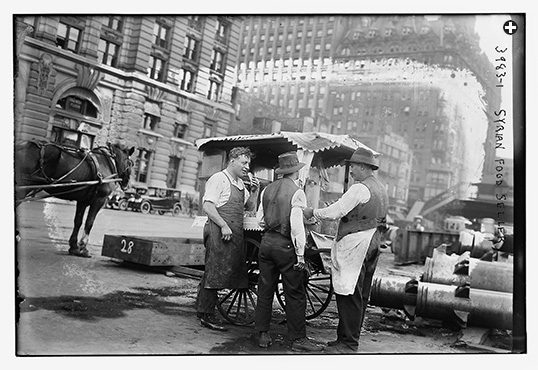

| In the early 1900’s, New York’s pushcart food vendors often could earn double the income of factory workers. |

The area saw a dynamic coming and going during those years. From a place of both residence and business for immigrants of all social classes, it slowly sorted itself out as the locus of shops owned by those who sold peddling goods to their less-well-off itinerant compatriots; the latter rented rooms in its cramped tenements between long-distance trips that reached as far as the mining camps of the American West. As the eminent Lebanese–American historian Philip Hitti wrote in his first book, The Syrians in America (1924), “Trade takes a man far.”

|

| Courtesy of Carl Antoun (3) |

| From top: Tailors, dry goods merchants and even entertainers were among the many who found niches in and around Little Syria. |

With the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 and the East River subway tunnel in 1910, the more salubrious outer boroughs became accessible, and those who were able moved their families away from Manhattan, leaving the peddlers behind. By 1935, Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue was described as “the new Washington Street.”

Accurate numbers of the Arabs living on Washington Street are not available, partly because they were registered as “Syrians” upon arrival but in later census counts were identified as “Turks.” One estimate was of 300 families in 1890. In 1904, a newspaper estimated a total of 1300 people. The total number of Arab immigrants admitted to the United States between 1899 and 1907 was 41,404, and 15,000 more arrived in the following three years. Few of those later arrivals, however, ended up in Little Syria.

One who did not was Salom Rizk. Arriving from the quiet Syrian village of Ain Arab in 1925, he took one look at the city and bought a ticket on the first train to Sioux City, Iowa. “New York was overwhelming,” he wrote, “an unbelievable jumble of swiftness and bigness—millions of people, millions of cars, buildings, windows, lights, noises—a great mass of vagueness swimming and spinning in my eyes.”

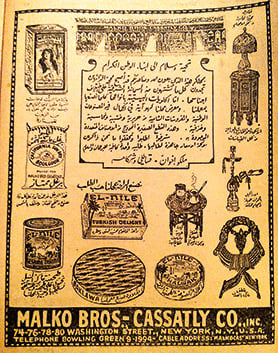

But those who stayed made Little Syria famous. A New York Times writer visited in 1899, marveling at the merchandise of the many peddling emporia, as well as Abrahim Sahadi’s grocery, founded there in 1895. Invoking the metaphor of Aladdin’s cave, the reporter was awed by swords and lamps hanging from the ceiling, glass bracelets of many colors and narghiles with their “fixings,” yet disappointed to find “no langourous eyes nor red fezzes.”

Sahadi & Co. is going strong today on Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue after a nephew broke away and established a new store there 60 years ago, following his Arab customers. Current owner Charlie Sahadi remembers his great-uncle Abrahim’s original grocery, which remained on Washington Street until 1967. “The retail counter sold nuts and dried fruits to a very different clientele from its early days,” he says, “yet they still made their own halvah and sesame bars and apricot paste.”

Business became an extended-family affair. Charlie’s father, Wade, who arrived from Zahle, Lebanon in 1919, became Abrahim’s traveling salesman, riding the train into the American Midwest to take wholesale orders. Uncles in Lebanon supplied them with the spices and grains unavailable elsewhere, as well as the brass trays, coffeepots and mortars and pestles that Arab cooks insist make all food taste better.

|

| Courtesy of Carl Antoun |

| The press often featured Little Syria among the city’s “exotic” immigrant scenes. |

The Arbeely family founded New York’s first Arabic newspaper, Kawkab Amrika (Star of America), followed by another named Al-Hoda (Guidance), both printed on Washington Street. Marian Sahadi Ciaccia (no relation to the grocer family of the same name), whose father came from Jeita village and whose mother came from Lebanon via the West Indies, remembers delivering Al-Hoda to subscribers as a teenager. “It kept me busy after school, and I made a nickel for each delivery,” she says. “I couldn’t read it but I did speak Arabic with my father. It was like our private language, because Mother didn’t speak it very well.”

Those who couldn’t read Arabic could keep up with local news in the English-language Syrian World. Its first issue, in 1926, included a work by the great Lebanese-born poet Kahlil Gibran exhorting cultural assimilation. However, Gibran’s invocation of such rarefied authors as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry James in his “Message to Young Americans of Syrian Origin” may have gone over the heads of his readers.

|

| Berenice Abbott / Federal Art Project / New York Public Library |

| Laundry dries on lines outside a lone six-story tenement at 37 Washington Street, dwarfed by the commercial buildings that, by the mid-1930’s, were transforming Little Syria. |

While Arab immigrants could get ahead in America, they faced cultural hurdles. Social reformer Jacob Riis fell into the trap of stereotyping the less favored in How the Other Half Lives, his 1890 book on New York tenement life. His chapter on homeless children carries the term “street arab” as its title, now regarded as an ethnic slur.

Syrian–American Alixa Naff, founder of an archive of Arab–American history at the Smithsonian Institution and author of Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience, 1880–1950, estimates that a peddler in 1900 would have cleared $1000 a year, while a factory worker would have earned barely half that. But it was not easy work. Ameen Rihani, who came to Little Syria in 1888 at age 12, wrote about the advantages of a peddling job in his autobiographical novel, The Book of Khalid, noting, “We travel and earn money; our compatriots, the merchants, rust in their cellars and lose it.”

Khalil Sakakini came to New York in 1908 and wrote in his memoir of having to move at top speed just to stay in place: “The American walks fast, talks fast, and eats fast.... A person might even leave the restaurant with a bite still in his mouth.”

Yet the pace of life on Washington Street was not all at double time. The restaurant owned by a man named Arta—a non-English speaker described by the Times as “fezzed, but all his other garments quite American”—became a coffeehouse during evening hours, its air filled with the clack of dominoes played hard on the table, wafts of pipe smoke and the scents of kibbe, laban and eggplant dishes—“tasty and delicate, neither French nor Teutonic”—that sold for 10 cents each.

Such was the setting for “Anna Ascends,” a 1919 Broadway play later made into a silent film by Victor Fleming, better known as the director of “Gone with the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz.” The plot revolves around Anna, a Syrian girl working in a coffeehouse that she doesn’t know is the front for a gang of thieves. At the end, she finds an American husband and happily assimilates into American culture. Act i begins with Anna busy arranging garlic wreaths and cans of olive oil, unmistakable markers of a Middle Eastern immigrant.

Not far from where the fictional Anna might have served coffee stood St. Joseph’s Maronite Church, established in 1891, the home parish of many of the neighborhood’s Syrian Christians. A marriage announcement in the Times from 1897 describes the wedding of Miriam Azar, from Jaffa, Palestine, to Touma Elia. Agog with Orientalist fascination, the article tells of the bride hidden by a “veil of curious lace,” while a baby bawled in the church, “presumably in pure Arabic.”

|

| Somach Photo Service / MTA Bridges & Tunnels Special Archive |

|

| John D. Morrell / Brooklyn Historical Society |

| In the 1940’s, construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, top, tore through the lower part of Little Syria, further hastening migration to Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, above, which remains a hub of New York's Arab–American community to this day. |

As Arabs left the neighborhood, St. Joseph’s emptied too; it was sold and demolished in 1984. Much of its masonry went as fill into new construction sites near the World Trade Center. Bishop Stephen Hector Doueihi remembers getting a call in October 2002 when he was presiding bishop at Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Cathedral in Brooklyn Heights. A broken cornerstone, with three words in its inscription indicating its Maronite origin, had been unearthed by a bulldozer clearing Ground Zero. Would the bishop’s cathedral care to have it to display?

“It was both a big surprise for us and a big honor,” remembers the bishop. “We knew we had once had a humble church near the World Trade Center site, but it had long ago been torn down. And then suddenly we hear that its Latin cornerstone, which had already been moved several times as St. Joseph’s had relocated over the years, had been found.... Truly it was like the fathers of many of our own parishioners—on the move from place to place.”

A happier outcome occurred not far from St. Joseph’s last address at 137 Cedar Street. St. George’s Syrian Catholic parish, established in 1889, built itself a neo-Gothic church at 103 Washington Street in 1925, enlarging a building that had been a boardinghouse, an Arab restaurant, a loan office for recent immigrants and the H&J Homsy—a family name from Homs, Syria—garment factory. Beirut-educated architect Harvey Farris Cassab designed a new terra-cotta facade. After a six-year review, the New York Landmarks Commission granted the church building, now under different use, full protected status in 2009.

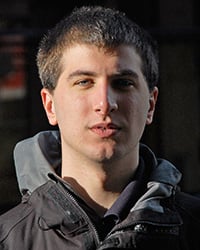

Carl Antoun is the 20-year-old descendant of Tanios Sadallah, who came to America from the village of Baskinta in 1891 and quickly returned to fetch his family, settling in Little Syria to open a silk-importing business. “I grew up in the borough of Queens and knew nothing of the Lebanese side of my family’s early days,” Antoun says while leading a walking tour of Washington Street. “When I found the old business records, written in Arabic, at my grandmother’s house, I wanted to learn more, which led me here.”

There is not much of Little Syria’s original architecture for Antoun to point out. A new hotel is going up on one side of St. George’s; a community house built by a benevolent society in 1925 and an older tenement building are in danger of being torn down on the other. Antoun’s organization, Save Washington Street, is lobbying to preserve the community house, which served as an adult-education school and clinic for new immigrants. Its exterior architecture, an amalgam of American styles called Colonial Revival, symbolized the cultural assimilation that was going on indoors in its English-language and citizenship classes.

Journalist Konrad Bercovici described life in Little Syria in the early 1920’s in his book Around the World in New York, a study of all the city’s immigrant communities. “A descent upon the Syrian quarter is like dream travel,” he wrote. Everything there seemed exotic to Bercovici, an immigrant from Romania himself—its coffeehouses, jewelry shops, rug merchants and even the dried roots and fruits on sale “of all kinds that grow one knows not where and are put to one knows not what use.”

|

| David W. Dunlap / The New York Times / Redux |

| Today, the buildings at 103, 105-107 and 109 Washington Street are all that remain of Little Syria. Carl Antoun, whose great-great-grandfather settled here in 1891, founded Save Washington Street to help protect them. |

|

| David W. Dunlap / The New York Times / Redux |

Of the neighborhood’s cramped tenement buildings, he wrote that they had been the prosperous homes of “good Dutch burghers a hundred years ago.” For the Syrians, he suggested, they were but “a temporary tent.” As usual for outsiders looking in, he confounds their religion. Everything there reminded him of “Moslem fashion”—the floor seating, the dress codes, even the Christian prayer service at St. Joseph’s Maronite Church.

Lucius Hopkins Miller, a professor of religion at Princeton University who had taught in the Levant for three years, provided the only objective survey of Little Syria. Of its 454 families in 1904, he counted only one Muslim household, consisting of two individuals. He found that men and women engaged almost equally in peddling work, as in its factory jobs, while men outnumbered women working behind shop counters and women far outnumbered men in at-home sewing jobs.

Because of his fluency in Arabic and his familiarity with the home communities of the émigrés, Miller was able to get a unique insider’s view. While social-reformer Jacob Riis decried the state of their housing, Miller agreed with the municipal tenement inspector that the Arabs maintained higher standards of hygiene than other ethnic groups. But Miller, too, was not altogether free of bias. The peddler’s job, he said, “encouraged overreaching and deceit”; jobs in the neighborhood’s Turkish-cigarette factories were preferable, he felt, or in factories that made mirrors, suspenders or ladies’ housecoats.

Bercovici was perhaps overwriting when he described Little Syria’s “kavas [coffeehouses] and bazaars and belly dancing halls, zarafs [loan offices] and their own Arabic newspapers...” and labeled its residents as “a people of a different seed, of an older civilization that has ever been reluctant to the new, distilling a certain pigment into the dull greyness of our modern lives.”

Even today, in the shadow of the newly rising World Trade Center, the neighborhood still speaks clearly to those with the time to listen. Says Carl Antoun, the great-great-grandson of one of its earliest residents, “This place is like a history lesson for me. There is much still to learn here.”

|

|

| Courtesy Carl Antoun |

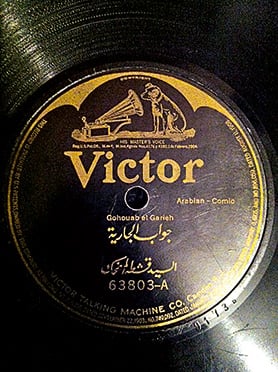

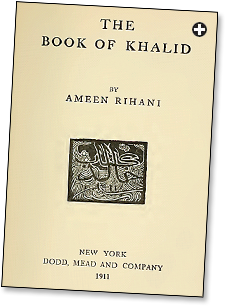

Though the best-known Arab writer in America is Kahlil Gibran, whose 1923 book The Prophet has been translated into some 40 languages with an estimated 100 million copies in print, the author of the first Arab novel published in the us was his compatriot Ameen Rihani (1876–1940), whose The Book of Khalid celebrated its centennial in 2011.

And while the former is considered an “easy read,” a bit trite and romantic, Rihani’s work is altogether different—so difficult that the novel quickly went out of print and has only recently been republished. Its dense plot as a reverse Orientalist saga set partly in America and partly in the Middle East, its Victorian vocabulary, calling to mind Charles Doughty’s Travels in Arabia Deserta and William Kinglake’s Eothen, and its winking references to such picaresque models as Don Quixote and Voltaire’s Candide, all make The Book of Khalid a challenge for the modern reader. But it offers a rich reward—and only in part because it was illustrated by Rihani’s dear friend Gibran.

Poet and literary historian Gregory Orfalea calls the book “overblown, using ten cent words the way someone might who pulls carelessly from a thesaurus.” However, he is altogether admiring of its attempt to contain the world within its covers, much as Walt Whitman attempted in Leaves of Grass, and he praises “the satiric wisdom that both celebrates and rebukes the immigrant’s fanciful hope, to good effect.”

Rihani came to America as child in 1888 and worked in his father’s peddling supply store on Washington Street for four years. Taken by the sights and sounds of New York, exposed to booksellers and stage actors and hungry for a formal education, he entered law school but soon fell sick and returned to Lebanon to recover. When he came back, he was ready to publish his articles and his translations of poems by the 10th-century philosopher Abu al-Ala al-Marri in the New York newspaper Al-Hoda, which introduced linotype printing to Arabic journalism worldwide.

During his second extended trip back to his ancestral mountain village of Freike, Rihani began to write The Book of Khalid, in English. It is based as much on his experience as an impressionable young man in New York as on the principles of self-reliance, rational thinking and superior achievement available to a man who acts alone. Indeed, that is an apt description of the adult Rihani, as his later career as a diplomat for the nascent country of Saudi Arabia, as a travel writer of books in English and Arabic and as a multicultural man of letters in Paris and New York all attest.

A scholar of Arab–American literature, the late Evelyn Shakir, has written that to be accepted in New York intellectual circles, Rihani and his compatriots first had to “dress carefully for their encounter with the American public, putting on the guise of prophet, preacher, or man of letters.” The aim: to become “an Oriental spokesman,” who could legitimately invoke the Orientalist clichés of Eastern mystic, exotic sage and desert denizen, as a character in The Book of Khalid says.

|

| Courtesy Carl Antoun |

The book’s plot, a kind of “vision quest” conducted by Khalid as he grows to manhood, shifts from New York to Lebanon and from Damascus finally to the Egyptian desert, where Khalid mysteriously disappears from the face of the earth. The Book of Khalid is structured as a “found manuscript” much like Don Quixote, which Cervantes playfully claimed had been copied, translated and edited from a text by its original Arab author Cide Hamete Benengeli. Going one better, Rihani claimed two sources for his book—Khalid’s Arabic autobiography and a French biography written by Khalid’s sidekick Shakib.

Wa’il Hassan, professor of comparative literature at the University of Illinois, sees in The Book of Khalid a number of the same ambiguities and hidden messages that the late Edward Said teased out of many classic Orientalist texts—but this from the pen of an Arab. Hassan notes Rihani’s almost comic name-dropping of Arab literary forebears and his Arabic-to-English wordplay and use of untranslated Arabic vocabulary. He calls it more an “Arabized English novel” than an Arab–American one.

As a soul-starved immigrant in New York, Khalid falls under the spell of a visionary used-book seller named Jerry, as in the Prophet Jeremiah, but also remembers he must fill his belly with mojadderah (a Lebanese dish of lentils and grains)—a word that comes from the same root as “smallpox.” Rihani plays the English meaning of “sham” off its homophone, the Arabic name for Syria. As Hassan notes, Rihani was writing for a reader who could swim equally well in both languages and cultures—in other words, someone like himself.

Todd Fine, executive director of Project Khalid, an international initiative to commemorate Rihani’s novel, has done the most to bring it back into the public eye. In honor of the centennial, he organized seminars at the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library and the Arab American National Museum. He has arranged for a new printing to be distributed by Random House, and has helped two Arab–American congressmen to introduce a resolution honoring the author.

Fine recognizes the irony of his current passion if compared to his past. Though a former assistant to the late Samuel Huntington, author of The Clash of Civilizations and theorist of cultural determinism, he now espouses the importance of an Arab author who stands against all this. “To me, Rihani represents everything that can go right when cultures meet,” he says.

This East–West dialogue that Rihani carried out in fiction was nothing less than an attempt at the synthesis of civilizations. As the narrator of The Book of Khalid notes, “What the Arabs always said of Andalusia, Khalid and Shakib said once of America: a most beautiful country with one single voice—it makes foreigners forget their native land.”

Did Rihani succeed? One hundred years later, people are still asking that question.

Acknowledgments

The editors thank Elizabeth Barrett-Sullivan, Todd Fine and Carl Antoun for their generous assistance.