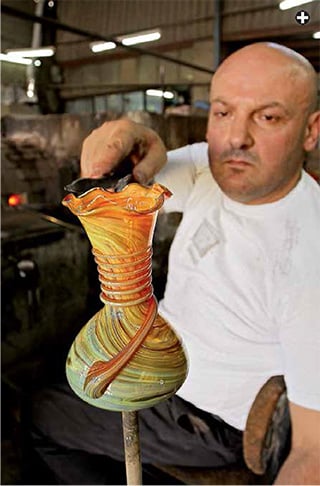

It’s a fine morning in June and the Mediterranean sun is blazing down on the West Bank city of Hebron. Its domes and minarets throw deep, welcome shadows onto dusty streets. Inside the Hebron Glass & Ceramics Factory, the temperature is even warmer, and it’s hotter still as I approach the furnace where 43-year-old Imad Natsheh is creating the glass that, for centuries, has brought Hebron renown throughout the world.

“My family has been blowing glass in Hebron for around 700 years,” Imad tells me as he works the glass, his fingers moving deftly despite the swelter. “I learned the craft from my father, and he from his father. I started to learn when I was five or six years old. Glass was my toys.”

mad picked up his English, he says, from the tourists who’ve visited his workshop over the years—including former us president Jimmy Carter, he points out. As Imad talks, the whirring fans around him barely make a dent in the heat. With the furnace running at 1400 degrees centigrade (2550°F), 20 hours a day, this is hardly surprising.

mad picked up his English, he says, from the tourists who’ve visited his workshop over the years—including former us president Jimmy Carter, he points out. As Imad talks, the whirring fans around him barely make a dent in the heat. With the furnace running at 1400 degrees centigrade (2550°F), 20 hours a day, this is hardly surprising.

It’s clear that glassblowing is more than just a job for Imad—it’s an obsession. And like most obsessions, it demands personal commitment. “I work around 10 hours a day, six or seven days a week,” Imad says. “And while I’m working, I don’t eat. No breakfast, no lunch. But I drink at least 20 liters of water a day.” During Ramadan, when he can’t drink during daylight hours, he works at night.

|

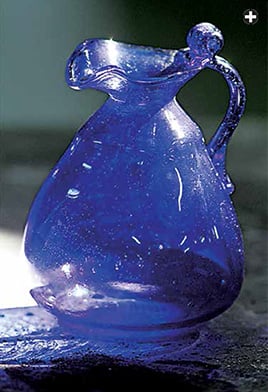

| Above: Using a technique developed first by Phoenicians some 2000 years ago, Imad Natsheh puffs gently through his blowpipe to "free-blow" molten silica. Minutes later, he uses pliers to add a handle and form a pitcher, top. Below: Ceramics are part of the family business, too. |

Imad is demonstrating the craft that has made the Natsheh family preeminent among Hebron’s glassmakers. First, he thrusts a thin metal blowpipe into the bowels of the furnace, into the incandescent pool of molten silica. With a twist of the pipe, he plucks out an igneous blob called a “gather.” He lays this on a metal plate. Putting the blowpipe to his lips, he puffs and rolls the red-hot glass until it begins to expand, then removes it from the plate and blows again, twirling the blowpipe in his fingers. With a pair of long pliers, he teases the glowing orb until a clearly recognizable vase-shape begins to emerge.

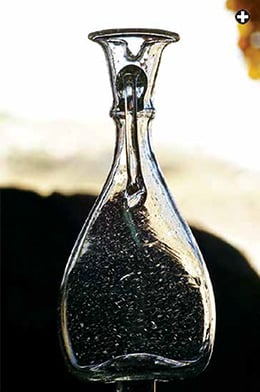

“The sand gives us colorless, or ‘white,’ glass,” Imad explains. “But Hebron is most famous for its blue and turquoise colors. We make the dark blue by adding cobalt to the melted glass, and the turquoise by adding copper. We cook the copper in a special oven at around 700 degrees centigrade [1300°F] for one month, and it becomes like powder. After we’ve finished blowing, we decorate the glass by hand.”

Imad works quickly. The fire is fading as the liquid sand solidifies into glass. It’s an age-old alchemy that, even with today’s abundance of cheap glassware, still seems magical. Apart from a few subtle changes, it’s a method that has been practiced in Hebron since at least the Middle Ages, and perhaps much longer.

|

| Though the craft was developed much earlier, it was in the Middle Ages that Hebron’s glassmakers first won fame. Hamed Natsheh, above right, handed off glassblowing to younger members of the family in the 1990’s, “when the tourists stopped coming” due to the political tensions that have made travel to and from Hebron difficult ever since. |

Around 50 bce, Phoenicians living along the coast of the eastern Mediterranean developed the art of “free-blowing,” in which air is blown into glass to shape it without using a core or a mold. It was also the Phoenicians who moved glass-making inland to such cities as Hebron.

Founded as long as 8000 years ago, Hebron is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities. Believed by Jews, Christians and Muslims to be the burial place of the patriarchs Abraham (“Ibrahim” in Arabic), Isaac, Jacob and their wives, it’s regarded by all three faiths as a holy city. Its name in Arabic, Al-Khalil, means “friend,” and “Friend of God” is the epithet ascribed to Abraham in the Bible and the Qur’an. At 900 to 950 meters (1460–1540') above sea level, the city enjoys one of the best climates in a region traditionally famed for grapes, ceramics, pottery and glassware.

By the time the Phoenicians invented free-blown glass, their influence was already waning. It was the Romans who disseminated the technique around the Mediterranean. Then, in the Middle Ages, historians concur that it was the Mamluks, who ruled from Anatolia to North Africa, who led the revival of glass-making in the eastern Mediterranean, then known as Greater Syria, in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Nazmi al-Jubeh, historian of architecture and archeology at the universities of al-Quds in Jerusalem and Birzeit in Ramallah, writes of Hebron that the glass industry had “a tremendous effect on the city’s economic growth in the 13th century,” leading to a consolidation of trade ties with Damascus, Jordan and Egypt. By the 14th century, glass from Hebron was being exported across the Middle East in heavily guarded caravans that carried it in specially designed wooden boxes to protect the valuable, fragile cargo.

|

| Hebron, or Al-Khalil in Arabic, is among the oldest continuously inhabited cities. Among its 13 historic neighborhoods is the harat al-qazzazin, or glassblower’s quarter. Left: Recently cleaned and renovated, locally made glass fills the

windows of the Ibrahimi Mosque. |

Hebron’s medieval reputation in glassmaking is corroborated by some of the many Christian pilgrims who visited the city over the centuries. Between 1345 and 1350, Franciscan monk Niccolò da Poggibonsi noted that “they make great works of art in glass.” In the late 15th century, the German friar Felix Faber and his companions also stopped in this “exceeding ancient city,” and he described how “we came forth from our inn, and passed through the long street of the city, in which work-people of divers crafts dwelt, but more particularly workers in glass; for at this place glass is made, not clear glass, but black, and of the colors between dark and light.”

In the 16th century, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Palestine saw glassmaking flourish through commerce between Palestine and Turkey. Hebron expatriate communities thrived in Cairo and Kerak, Jordan, where they marketed the city’s crafts. In the 1740’s, business was still booming, according to another Italian pilgrim, Abbot Giovanni Mariti. He wrote: “A trade is carried on at this city in small glass toys of different colors, such as rings and globes, which are used for ornamenting the women and camels of the Arabs. These articles are sent to every part of Egypt and Syria.”

|

|

| “The sand gives us colorless, or ‘white,’ glass,” explains Imad. “But Hebron is most famous for its blue and turquoise colors,” which he makes by adding cobalt and copper, respectively, to the molten sand. |

And 141 years after that, in 1881, Alberto Bacchi della Lega, the editor of Niccolò da Poggibonsi’s Libro d’Oltramare, noted similarly that “the art of glass-making is still flowering there, and they principally make bracelets in colored glass which they transport to all parts of the Turkish Empire and Egypt.” Late 19th-century Islamic court records show that there were 11 glassmaking factories in Hebron. It was only in the early 20th century that stiff competition from European markets left the Natsheh family to continue alone the tradition of making glass in the old way—the situation that continues to this day.

The Ottoman connection still shows in the family: Raslan Natseh, 48, whose grandmother and whose given name are both Turkish, recalls family memories that stretch back generations. “Over the centuries, many Palestinians went to Turkey to serve as soldiers for the Ottoman Empire,” he tells me over cardamom-scented Turkish coffee in his Hebron workshop. “When they returned, they brought the skills back with them, from generation to generation. My own grandfather was a soldier in Istanbul, and he taught me how to blow glass.”

But what was it about Hebron that stimulated both the production and trade of this exquisite yet functional material? The answer is geological, geographical and religious. Hebron’s immediate environs provide sand that is well suited to glassmaking, and at the Dead Sea, just 25 kilometers (15 mi) to the east, there are both the soda ash (sodium carbonate, Na2CO3) essential to glassmaking as well as the clay from which to build furnaces.

In addition, some consider the city the fourth-holiest site in Islam, where pilgrims come to pay their respects at the Tomb of the Patriarchs, and it lies on the pilgrimage route that connects Jerusalem with Makkah. Hebron’s position on a natural crossroads leading south to Arabia, east to Jordan, west to the Mediterranean Sea and north to Damascus made it a commercial hub. All the traffic traveling through Hebron, whether religious or mercantile, also passed through its markets, where Hebron’s glassmakers and other craftsmen sold their wares. And, just like modern tourists, pilgrims would buy souvenirs to take home and enjoyed watching the glassblowers at work, just as they do today.

Yet today, far fewer travelers pass through. Since the Israeli closure in the 1990’s of all but one Palestinian road into the city center, the Natsheh family’s workshop, and others that produce glass by more modern methods, as well as other craftspeople, have all moved to Ras al-Jura, a suburb on the north side of town.

|

| Turning while blowing helps keep a semi-molten glass gather symmetrical. |

Though quieter now, the city center is still its historic heart. Alaa Shahin of Hebron Municipality was responsible for the city’s application this year to the World Heritage Sites list administered by unesco, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. We walk together through the old city, where Mamluk architecture still dominates. I admire its golden limestone, atmospherically dim alleyways and refreshingly shady squares.

“We have 13 quarters in the old city,” Shahin says. “Each one has a different economic or social profile, depending on the kind of activity practiced or its ethnic makeup—the Kurdish quarter, Jewish quarter, Iraqi quarter, Moroccan quarter, and so on. For example, the Kurdish quarter was inhabited by families who came with Salah al-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub [Saladin] in 1187—he was a Kurd, of course. The main artery of the suq [market] connects all these different components of the city to each other, and to the Ibrahimi Mosque.” The beautifully renovated buildings around me are the work of the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee (hrc), which is restoring the homes and craft workshops of Hebron’s citizens to breathe life back into the city, in the hope that both locals and tourists will return.

|

| Pliers give final shape to this vase as it cools, streaked with colors and wrapped in a decorative spiral. |

We arrive at the harat al-qazzazin, the glassblowers’ quarter, and the Hosh Natsheh, the area named after Hebron’s most famous glassblowing family. “We’ve finished restoring much of the infrastructure of the old city. Now we’re restoring the shops in the suq,” Shahin explains. It is in the Hosh Natsheh that the municipality, working with the hrc, is planning to create an academy to train young people in traditional crafts, including glassmaking. Zbyněk Wojkowski, a spokesperson for the hrc who—for local convenience—goes by “Sami,” explains that, in addition to providing workshops and training areas for craftsmen, “the academy will also allow us to research the history of our handicrafts and the materials used. In this way,” he says, “we hope that Hebron’s traditional crafts will thrive once more.”

The streets of the qasabah, or old city center, lead me to the Ibrahimi Mosque. Here I see the most dazzling displays of Hebron’s glass history. The roof’s dome is pierced with stained-glass windows in jewel-like colors: scarlet, gold, turquoise and blue—this last particularly favored among Arabs. According to the hrc’s Walid Abu-Alhawaleh, the hrc has recently renovated the mosque’s glass “millimeter by millimeter,” especially in the dome, built during the Mamluk period to showcase Hebron’s pre-eminence in glass. (It’s also Hebron glass that embellishes Jerusalem’s most celebrated Islamic building, the Dome of the Rock.)

ack in the days when the glassmakers’ clientele was chiefly locals and pilgrims, homewares and jewelry—especially beads—were the preferred products. Now, most of the glassware produced is sold out of the city and exported, and the merchandise reflects that. Nader Tamimi, chair of the Association of Traditional Industries in the Palestinian Authority, explains that this shift came after the 1987 Palestinian intifadah, or uprising, and the Israeli restrictions that followed.

ack in the days when the glassmakers’ clientele was chiefly locals and pilgrims, homewares and jewelry—especially beads—were the preferred products. Now, most of the glassware produced is sold out of the city and exported, and the merchandise reflects that. Nader Tamimi, chair of the Association of Traditional Industries in the Palestinian Authority, explains that this shift came after the 1987 Palestinian intifadah, or uprising, and the Israeli restrictions that followed.

|

| Holiday decorations have helped Hebron glass reach contemporary global export markets. |

“Twenty-five years ago, hundreds of tourists came to Hebron every day, and we had no export market,” he says. “Now that Hebron is off the tourist map, we’re trying to open new markets, exporting to European countries, the usa, Canada. This market demands different products, with a decorative rather than utilitarian function: baubles for Christmas trees, bells, chalices, beads and drinking glasses, painted in elaborate designs.”

|

| With fresh air

behind the heat of the workshop and a glass of tea at his

right, Imad Natsheh rolls glowing glass to help it stay round. |

Hamed Natsheh, 80, has personal experience of the change Tamimi describes. Dressed in a pristine white thawb, he brightens when he speaks of his recollections of a life spent working with glass. “My family has always worked in glass, my grandfather, my great grandfather. We made bead ‘eyes,’ necklaces and the clear medicine bottles that the doctors used to carry around.” As a young man, Hamed went to Cairo to teach his methods to young Egyptian craftsmen. When the tourists stopped coming to Hebron, he closed his business and let other members of his family carry on. “Today we make a much wider range of products,” he says.

Hamed’s younger relative Imad, whom I had met earlier in the workshop, agrees with his elder about today’s difficulties. “When I was born, there were around 15 glass manufacturers in Hebron, based in the old city,” he says. “Now, my cousin and I are the last two glassblowers in our family. This is a very hard job. Our children have Facebook and iPhones and they want to go to university instead. But I continue, because I love it.” Each year, Imad travels a couple of hours north to the Birzeit Festival near Ramallah, where he builds a small furnace to demonstrate his craft, and he has also been invited to demonstrate in Tel Aviv. It’s clear that there’s still interest in glassblowing, with room for further exploitation by Palestine’s tourism authorities.

In the Hebron Glass & Ceramics Factory, Imad is putting the finishing touches on his vase. He cuts off one end with the long pliers and, with a strand of molten glass fresh from the furnace, he adds an elegant handle. He pinches the lip—and the vase becomes a pitcher. Around him a gaggle of Palestinian teenagers from Jerusalem, out on a school field trip, have gathered to watch, but Imad’s concentration doesn’t waver. Like a top athlete, it’s clear he has entered a mental state where instinct, tempered by a lifetime of acquired skill, takes over. He’s “in the zone.”

The whole process has taken perhaps 10 minutes. Now, Imad puts the glass into an adjacent annealing oven, heated to a mere 550 degrees centigrade (1020°F), where it will stay for six hours. Let it cool any faster, he says, “and the glass will shatter.”

|

| Inside the Natsheh’s family store. |

Taking me to the back of the workshop, he shows me high piles of broken bottles in three colors—green, brown and clear. “These days we recycle broken glass, and mix it with the sand.” Melting the broken glass in the oven, they then color it using pigments they usually import nowadays rather than making it themselves. And instead of olive wood to fire the furnace, as in the old days, they now use recycled engine oil.

Back at his furnace, Imad pauses to sip one of the many glasses of tea brought to him throughout the day by his young son, Yusef. The boy is helping his father and the fellow glassblower sitting on the other side of the furnace, as well as the ceramists working at the back of the family factory. But Imad won’t pressure Yusef into going into the family business. “He must choose his own life,” he tells me.

Imad is now making a delicate swan, using another style of glass that is proving popular among his customers. Semi-opaque, the glass is interlaced with fine swirls of pale turquoise, green and blue. It seems to glitter from within. Imad calls this “Phoenician style,” after the glass found in archeological sites and which his family has recreated through trial and error over the past 30 years. The recipe? “It’s a family secret!” he smiles.

All he will disclose is that he makes everything by hand, from beginning to end. “You can’t use a machine to do this work,” he says. “The old ways are best.”

|

Historian and travel writer Gail Simmons (www.travelscribe.co.uk) surveyed historic buildings and led hikes in Italy and the Middle East before becoming a full-time travel writer for uk and international publications. She holds a master’s degree in medieval history from the University of York and is currently earning her Ph.D. She lives in Oxford, England.

|

|

Photojournalist and filmmaker George Azar (george_azar@me.com) is co-author of Palestine: A Guide (Interlink, 2005), author of Palestine: A Photographic Journey (University of California, 1991), and director of the film “Gaza Fixer” (2007). He lives in Jordan. |