|

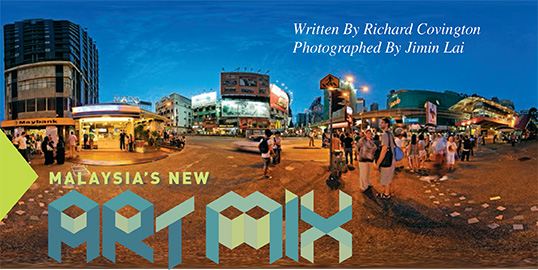

The pulse of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia’s capital and, with nearly 2 million people, its most populous city, beats strong amid the malls, restaurants and galleries of Bukit Bintang “Star” Walk. Many are new in the past decade. “This is really the best time to be an artist in Malaysia,” asserts Bernice Chauly, 43, an author, photographer and actress. The pulse of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia’s capital and, with nearly 2 million people, its most populous city, beats strong amid the malls, restaurants and galleries of Bukit Bintang “Star” Walk. Many are new in the past decade. “This is really the best time to be an artist in Malaysia,” asserts Bernice Chauly, 43, an author, photographer and actress. |

he music pulses, and so does the country. In a hip-hop video shot in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur, Chinese and Malays in a tea shop, Malays in a mosque, Tamils in a jewelry store, conspicuously multi-ethnic throngs mingling in markets, schools, skyscrapers and parks, all urge one thing: Undilah—“Vote” in the Malaysian Bahasa language. Hip, catchy and nonpartisan, the video is a testament to diversity and optimism, aimed at rocking the vote in advance of the general election that Malaysia’s constitution requires by June 27, 2013.

he music pulses, and so does the country. In a hip-hop video shot in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur, Chinese and Malays in a tea shop, Malays in a mosque, Tamils in a jewelry store, conspicuously multi-ethnic throngs mingling in markets, schools, skyscrapers and parks, all urge one thing: Undilah—“Vote” in the Malaysian Bahasa language. Hip, catchy and nonpartisan, the video is a testament to diversity and optimism, aimed at rocking the vote in advance of the general election that Malaysia’s constitution requires by June 27, 2013.

Among the faces in the video is that of Nurul Izzah Anwar, a 32-year-old member of parliament, amateur guitarist and Radiohead fan who has parlayed her family connections as the daughter of former deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim into a platform of tolerance and equal opportunity. Visiting her at home in the leafy Mont Kiara neighborhood of Kuala Lumpur, I’ve come to talk not about politics, but about the contemporary arts and culture scene.

It’s been growing, she explains, at a dizzying pace, ever since elections in 2008 brought a “great opening for more freedom of expression,” which, she adds, “unleashed the arts.” The “Undilah” video, conceived by the country’s best-known music producer, Pete Teo, is a prime example of Malaysian artists embracing politics, “bringing us together at a level that was unheard-of before,” marvels Nurul Izzah, who, like many Malaysians, generally goes by her given names.

|

Opened in 1998, the Islamic Arts Museum of Malaysia is home to one of Asia’s leading collections. Like most Malaysian arts institutions, it is privately funded. Opened in 1998, the Islamic Arts Museum of Malaysia is home to one of Asia’s leading collections. Like most Malaysian arts institutions, it is privately funded. |

All across Malaysia, but especially in the capital, nicknamed KL, a younger generation of artists, musicians, composers, writers, performers, designers and filmmakers is redefining culture and enlivening the landscape with an astonishing variety of imaginative verve. The energy is palpable. On a recent visit, I sat in on a feature film shoot, watched a fashion show, attended art openings and symphonic concerts, witnessed an experimental theater piece on river pollution, and stayed up late at a jazz club and even later at a memorable party where a saxophonist and singer belted out tunes to a hundred or more guests from KL’s creative and financial communities—all in 13 days.

“This is really the best time to be an artist in Malaysia,” asserts Bernice Chauly, 43, an author, photographer and actress. “People want to be heard, and they are willing to take risks, to use their own money to make it work.”

I was speaking to Chauly on a lunch break during the filming of “Spilt Gravy on Rice,” an adaptation of a hit play written by the popular Malaysian actor and comedian Jit Murad. The plot revolves around a family patriarch and his children’s plans to manage his legacy after his death. Although the witty exchanges among siblings draw laughs, it’s a generational conflict that also grapples with the challenges the increasingly middle-class, 54-year-old parliamentary democracy faces in sharing wealth and power and in making its ethnic diversity a source of strength.

|

Nurul Izzah Anwar, 32, was elected to parliament on a platform of tolerance and inter-ethnic opportunity. National reforms in 2008, she says, have “unleashed the arts” in Malaysia, “bringing us together at a level that was unheard-of before.” Nurul Izzah Anwar, 32, was elected to parliament on a platform of tolerance and inter-ethnic opportunity. National reforms in 2008, she says, have “unleashed the arts” in Malaysia, “bringing us together at a level that was unheard-of before.” |

A Muslim-majority state that became independent of British colonial rule in 1957, Malaysia has accomplished remarkable economic growth in a short time. Forty years ago, half the Malaysian population lived in poverty, and per capita income was us$260 a year. Today, just four percent of the nation’s 28 million inhabitants live in poverty, and income per capita is $8400, according to the International Monetary Fund. The economy has benefited from substantial oil reserves and a thriving manufacturing sector, as well as—more controversially—exploitation of palm oil plantations and logging, at times in rainforests. But high-tech is also booming: A substantial proportion of Intel’s global output of computer chips, for example, is produced 400 kilometers (240 mi) north of KL in Penang, on the Strait of Melaka. George Town, a well-preserved enclave of shophouses—storefront residences—mosques and colonial architecture on Penang, was named a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (unesco) in 2008, along with Melaka, the 600-year-old port city that lies south of the capital by some 130 kilometers (80 mi).

|

As robust as the economy has been in recent decades, the arts are largely a do-it-yourself struggle, making do with support mainly from banks and a handful of other corporate sponsors, modest government help, the commitment of some 50 leading individual art collectors and, perhaps most important, the sheer stubborn passion of the creative sector itself.

There are, however, a couple of notably well-funded exceptions: Possessing one of the most impressive collections of its kind in all of Asia, the Islamic Arts Museum of Malaysia is run privately by the Albukhary Foundation, which is financed by power plants, ports and mining companies. Penang’s ThinkCity, which promotes arts, urban renovation, environmental and cultural enterprises, is underwritten by Khazanah Nasional, the investment arm of the Malaysian government. Apart from these and a sprinkling of others, the majority of today’s defiantly cheering success stories in the arts and design industries survive on scant, usually private, money and abundant, usually personal, dedication.

A decade ago, Raman Krishna, now 63, was visited at his bookstore, Silverfish Books, by an American professor friend from a Japanese university. “When he asked where the books by Malaysian writers were, I was so totally embarrassed by the fact that I could only locate a dozen titles that I was shamed into becoming a publisher,” Raman confides inside the small bookstore in KL’s upmarket Bangsar neighborhood.

It wasn’t the first time that Raman had indulged his inner Quixote to pursue an insistent quest. After 25 years making a living as a construction engineer, “I decided enough was enough,” he recalls. “I told myself that I should get on with my secret ambition to open a bookstore.” From his own savings, he plowed 250,000 ringgit (about $80,000) into the scheme and, in 1999, opened the doors at Silverfish.

Moving into publishing was an equally seat-of-the-pants gamble. He put the word out through newspapers, the Internet, friends and customers that he was planning on issuing an anthology of short stories. In a month, he received 250 submissions, so many that, after the first anthology appeared, he solicited entries for a second edition. More than 500 stories rolled in.

“I was astounded by the pent-up demand from writers wanting to express themselves,” he declares. Although his authors write in English, because it has long been the common language of educated Malaysians from all backgrounds, it is in fact only the country’s third most frequently used language, after Malay and Chinese, says Raman.

His bestseller so far is I Am Muslim, Dina Zaman’s funny, questioning portrait of Malaysian Muslims. At 12,000 copies, it’s a modest success by us standards, but “huge for an English-language book here,” crows Raman. He notes with obvious satisfaction that the volume has become class reading at both the University of California at Berkeley and the University of Chicago.

|

Raman Krishna, owner of Silverfish Books in Kuala Lumpur’s Bangsar neighborhood, determined he’d become a publisher, too, some 10 years ago after feeling “embarrassed by the fact that I could only locate a dozen titles” by Malaysian authors. Since then, he has shepherded some 40 Malaysian-author titles into print. Raman Krishna, owner of Silverfish Books in Kuala Lumpur’s Bangsar neighborhood, determined he’d become a publisher, too, some 10 years ago after feeling “embarrassed by the fact that I could only locate a dozen titles” by Malaysian authors. Since then, he has shepherded some 40 Malaysian-author titles into print. |

After 10 years in publishing, shepherding some 40 short-story collections, novels and non-fiction works into print, Raman believes that Malaysian authors have become more “color-blind.” Whereas Indian, Chinese and Malay writers used to concentrate on characters exclusively of their own ethnicity, they now cross ethnic, racial and religious barriers with ease, he observes. For example, an ethnic Malay storyteller like Rumaizah Abu Bakar is now accurately convincing in delineating the aspir-ations and frustrations of an ethnic Chinese chef. Similarly, the policeman-turned-crime novelist Rozlan Mohammad Noor intertwines all levels of KL society in his tangled stories.

“It’s the same in the country at large,” opines Raman. “People are saying, no, they do not want to be divided by race or ethnicity. It’s no longer a question of merely tolerating differences: It’s acceptance.”

arallel to this literary flowering is an uptick in film and visual arts. Around 1990, when Zarul Albakri initially tried directing films, he stopped after his first effort. “There simply was not enough talent,” he recalls. “Now, however, there’s a new generation and a lot more talent,” enthuses the 52-year-old filmmaker, “with actors, cinematographers, set designers, technical crew, the whole lot.” He is producing “Spilt Gravy on Rice” with his younger brother Zahim, 48, as the director.

arallel to this literary flowering is an uptick in film and visual arts. Around 1990, when Zarul Albakri initially tried directing films, he stopped after his first effort. “There simply was not enough talent,” he recalls. “Now, however, there’s a new generation and a lot more talent,” enthuses the 52-year-old filmmaker, “with actors, cinematographers, set designers, technical crew, the whole lot.” He is producing “Spilt Gravy on Rice” with his younger brother Zahim, 48, as the director.

|

An art collector and former diplomat, Malaysian National Gallery Director Yusof Ahmad oversees the museum’s dual exhibition strategy that offers both crowd-pleasers for first-time visitors as well as specialized shows. An art collector and former diplomat, Malaysian National Gallery Director Yusof Ahmad oversees the museum’s dual exhibition strategy that offers both crowd-pleasers for first-time visitors as well as specialized shows. |

When I met Zarul, the “talent” he now so admires was all around us, with the movie’s actors, actresses and crew gathered at the Albakri home for a farewell party before the bulldozers arrived to clear the ground for condominiums. Surrounded by towering trees and a lush garden, the estate was a holdout, one of the last single-family residences in central KL. “We shot part of the film inside and outside the house to document it for posterity,” says Zahim, who explained that his mother, brother, sister and he had decided to sell the place after his father’s death. “It’s sad, I know, but the party is kind of our New Orleans-style wake to celebrate family memories and mark a new phase.”

By chance, I ran into another movie director, U-Wei Bin Haji Sarri, at the National Visual Arts Gallery of Malaysia, where an exhibition of set designs, props, posters, storyboards, excerpted clips and other material from his eight features was on display. A former film student at The New School in New York, U-Wei, 57, has had his work screened at the New York Film Festival and the Cannes Film Festival.

When we spoke in July 2011, he had almost finished his latest undertaking, a cinema version of Almayer’s Folly, Joseph Conrad’s 1895 debut novel about a Dutch treasure hunter in 1830’s Malaysia. We watched the 10-minute trailer together: beautifully atmospheric, with visual echoes of another film shot in Malaysia—“Indochine” with Catherine Deneuve.

In one of U-Wei’s scenes, Arab merchants and Malays encounter English naval officers aboard a wooden sailing ship on a sluggish jungle river. “That was one really complicated sequence,” the director laughs, rolling his eyes at the recollection. “We had the ship built from scratch, and when it came time to move that monster along the river, I ended up pulling the ropes myself to tug it along, if you can believe it.”

Later, I interviewed National Gallery director Yusof Ahmad, an art collector and former diplomat who has introduced a series of innovative exhibitions intended to lure in first-time audiences. “The National Gallery has existed since 1958, almost as long as the country itself, but when I was appointed over a year ago, I found to my dismay that some of my friends did not even know where the gallery was,” Yusof admits. “That had to change.”

|

Founded in 1989 “purely to promote our own work,” says painter Bayu Utomo Radjikin, the Matahati gallery now prospers sufficiently to help fund artist-in-residence programs both for Malaysian artists abroad and other Southeast Asian artists in Malaysia. Founded in 1989 “purely to promote our own work,” says painter Bayu Utomo Radjikin, the Matahati gallery now prospers sufficiently to help fund artist-in-residence programs both for Malaysian artists abroad and other Southeast Asian artists in Malaysia. |

The museum director chose a two-pronged strategy: crowd-pleasing entertainments based on broad, popular themes like mothers and children, Ramadan and devotion to God, complemented by more focused exhibitions, including the presentation devoted to U-Wei’s films, that appeal to the art-house cognoscenti. So far, this one-two punch appears to be paying off.

“For the mothers-and-children show, we were deluged with people who had never been to the gallery before,” Yusof notes proudly. “It was the most well-attended exhibition we’ve ever had.”

While the National Gallery may not be as well known as it could—or perhaps should—be, it’s not for lack of talent: Malaysia is bursting with artists and private galleries.

alentine Willie is one of the pioneer art dealers in the country, and indeed in the Southeast Asian region, curating galleries in KL, Singapore, Yogyakarta and Manila. He is a great-grandson of a Borneo headhunter, and the trajectory of his life has been unexpected, to say the least. Willie was educated in London and later practiced law there before moving back to Malaysia 16 years ago to open his first gallery.

alentine Willie is one of the pioneer art dealers in the country, and indeed in the Southeast Asian region, curating galleries in KL, Singapore, Yogyakarta and Manila. He is a great-grandson of a Borneo headhunter, and the trajectory of his life has been unexpected, to say the least. Willie was educated in London and later practiced law there before moving back to Malaysia 16 years ago to open his first gallery.

“When I first started, there were maybe four galleries in KL. Now there are more than 20 selling serious art, not just ... wall decoration,” he sniffs. “This growth is an indication not just of the multiplying wealth of the buyers, but of their maturing sophistication as well.”

Willie is a persuasive advocate for turning Malaysia’s centuries-old position as a trading hub to its esthetic advantage. “Geography defines Southeast Asia,” he tells me over coffee in a café next to his Bangsar gallery. “When you are a little scrap of land in the middle of the ocean, you can’t stop people coming to you,” he continues. “You can’t defend yourself, so why try? It’s better to say welcome, take what you want, and let the rest go. That has been our genius. We welcome everyone, and we take from the foreign influences to generate our own art and culture.”

|

“There’s a new generation and a lot more talent,” says film producer Zarul Albakri, left, whose recent Spilt Gravy on Rice takes place in family whose generational tensions are metaphors for Malaysian culture. In his studio, he chats with fellow producer A. Samad Hassan. “There’s a new generation and a lot more talent,” says film producer Zarul Albakri, left, whose recent Spilt Gravy on Rice takes place in family whose generational tensions are metaphors for Malaysian culture. In his studio, he chats with fellow producer A. Samad Hassan. |

Willie suggests that the country’s scrumptious cuisine is a perfect example of his point, launching without ado into a mouth-watering rendition of its eclectic, three-part harmony. “You’ve got the steaming, clear flavors of southern Chinese cooking and the wealth of Indian spices added to the rich coconut dishes of the Malay kitchen,” he riffs, making us both hungry.

A few minutes’ drive away, in the suburban neighborhood of Petaling Jaya, another gallery owner is taking this open-arms approach a step further. Shalini Ganendra, also a uk-trained lawyer turned art dealer, has inaugurated a lecture series where international authorities on art, ceramics, photography, textiles and design share opinions and expertise with local artists, curators, collectors and students. Despite the overwhelmingly positive effects of fostering these East-West cultural bridges, Ganendra acknowledges a certain amount of risk.

“The challenge for Malaysian artists is not to become overly western-derivative, not to copy western styles,” she warns. Willie echoes her concern. “Artists here don’t have enough self-confidence,” he told me. “They think that who is good and who is not is dictated by western society instead of questioning standards for themselves.”

Cue an artists’ collective that appears to have self-confidence to spare—enough, in fact, to share its good fortune with dozens of emerging artists. Back in 1989, as newly minted graduates of the Universiti Teknologi mara, the country’s largest university, the five colleagues banded together to form Matahati, a Malay expression meaning “eyes of the soul.”

“We formed the collective purely to promote our own work,” explains 42-year-old Bayu Utomo Radjikin, as art-student volunteers arrange paintings for an upcoming opening in the House of Matahati gallery, which occupies two floors above a printing shop off a busy road in KL’s Ampang neighborhood. After about 10 years of supplementing their income by painting sets for theater, film and television productions, they became well enough established that they decided to give something back to a younger generation and forge a pan-Asian arts network in the process.

In addition to paying for fledgling Malaysian artists to go to Yogyakarta and Manila, Matahati uses a part of its gallery income to bring to KL their counterparts from those cities for month-long exchanges. The collective also provides studio space for Malaysian artists, introduces them to gallery owners and collectors and stages exhibitions of their work. Artists from as far away as Brazil and Japan are invited for residencies to allow them to interact with native painters and sculptors. The group also sponsors a program that dispatches Malaysian artists into schools to devise collaborative projects with the students and introduce them to contemporary art.

|

“I see Malaysia as more like a salad than a melting pot,” says composer Johan Othman of Penang’s Universiti Sains Malaysia. “You recognize the lettuce, tomato and all the varied ingredients. They’re not blended, but separate.” “I see Malaysia as more like a salad than a melting pot,” says composer Johan Othman of Penang’s Universiti Sains Malaysia. “You recognize the lettuce, tomato and all the varied ingredients. They’re not blended, but separate.” |

Compared to Matahati’s gradual ascendancy, the young designers of Ultra, all in their 20’s, have become overnight sensations, making waves in the fast-rising business of “ethical fashion,” which makes a point of using recycled materials. In a mere three years since launching the label in 2009, Ultra has already carried off the 2011 innovation award of the Ethical Fashion Forum in London, and wowed the fashion press in Paris. Despite their European acclaim, their elegantly minimalist styles are purely local Malaysian.

I met the company’s chief designer, Tengku Syahmi, 22, at a runway show by up-and-coming fashion designers that was held at MAP, a brand-new space for exhibitions and events at Publika, a mixed-use complex that combines apartments, galleries, restaurants, shops and offices in the hilly Hartamas neighborhood overlooking KL. Straining to hear Syahmi over the techno beat as models flounced past along the catwalk, I caught the gist of an invitation to visit the design studio the next day and readily accepted.

It turned out that Ultra’s atelier was located a floor below MAP. “Don’t look too closely at the designs for our next collection,” Ultra co-founder Anita Hawkins playfully admonished me, as I glanced at the sketches taped to the walls. “They’re supposed to be secret.” But the decidedly unglamorous studio is so cramped—with four or five designers bent over tables in a space about the size of an elementary schoolroom—that I can’t really avoid the drawings. They literally cover the walls.

“Touch this,” offers the 26-year-old Hawkins, inviting me to squeeze a hooded white dress hanging on a rack of dresses, coats and wraps. It feels like velvet. “Bet you’d never guess the fabric is made of wood pulp,” she teases, with a cheeky grin. She’s absolutely correct. Nope, I confess, wood pulp never crossed my mind.

How about this, she asks, holding up a chic black outfit. “Recycled plastic bottle caps,” she announces, relishing my astonishment. But why does it have the texture of wool, I wonder aloud. “That’s also our secret,” she replies.

The idea behind Ultra and other ethical fashion labels is to mount a counterattack against throwaway consumer culture and demonstrate that recycled, sustainable materials can be used to conjure up knockout styles. “We want people to be more aware of what they are consuming,” Hawkins asserts, “to buy what they need, not just grab everything they want.” This sounds like marketing heresy. Aren’t you afraid customers will buy less, I ask. “Maybe,” she responds—“but if they are willing to pay more for fewer items of good quality, we can still turn a profit.” And in fact, several months after I spoke with Hawkins, Ultra stopped production altogether—at least for the time being—to concentrate instead on downloadable designs for do-it-yourself clothing. Hawkins and others were also touring schools in the uk and elsewhere to drum up support for recyclable fashion and sustainable design.

ike Ultra’s designers, who travel to London, Paris, Shanghai and other fashion hubs to promote their creations, the new generation of artists, writers, musicians, composers and dancers follows a long-standing pattern of migrating overseas, then returning to Malaysia to expand domestic cultural horizons.

ike Ultra’s designers, who travel to London, Paris, Shanghai and other fashion hubs to promote their creations, the new generation of artists, writers, musicians, composers and dancers follows a long-standing pattern of migrating overseas, then returning to Malaysia to expand domestic cultural horizons.

“Historically, the country has always been a kind of crossroads, whether it’s for international trade or the spice route,” observes Hardesh Singh, a 35-year-old composer and producer of Internet video programs. “People leave searching for goods to exchange and bring knowledge and culture back. That’s just in our cultural DNA, to go abroad for a while and come back once you have spent your wanderlust. You contribute whatever seeds you’ve collected from elsewhere and sow them back here at home.”

|

London lawyer, pioneer art dealer and great-grandson of a Borneo headhunter, Valentine Willie now runs galleries in four countries. The growth of his and some 20 other galleries shows a “maturing sophistication,” he says. London lawyer, pioneer art dealer and great-grandson of a Borneo headhunter, Valentine Willie now runs galleries in four countries. The growth of his and some 20 other galleries shows a “maturing sophistication,” he says. |

As fate would have it, Singh and I are mulling over cross-cultural exchanges while sipping a frappuccino and a lowfat green-tea latte at a Starbucks. (The chain is another outsider welcomed to Malaysia with open arms.) He explains that music was always his passion, and so, after graduating from college with a fall-back degree in telecommunications engineering, he moved to San Francisco in the late 1990’s to study Indian ragas. Returning to KL around 2001, Singh began composing film soundtracks, and now he manages a recording studio, soundstage and digital production unit that spins out everything from advertising jingles to avant-garde concert music. One of his ventures, a network of Web video channels, is an attempt to bypass government-controlled television and give voice to a more independent media. Among the Webcasts—along with underground bands—are a political satire similar to America’s “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart,” in which freewheeling interview segments, co-hosted by the 31-year-old actor and political commentator Fahmi Fadzil, make for a breath of fresh airtime.

Singh laments that Malaysian music is not better known outside the country. “We don’t have a distinctive Malaysian voice that you’d think would come out of this cultural melting pot,” he acknowledges a bit ruefully. “We haven’t been as successful as Thailand and the Philippines—and are certainly way behind Africa and Brazil—in inventing a recognizable sound.”

The standout exception is contemporary classical composition, he adds, brightening. “We are making a lot of headway overseas, with commissions from orchestras in Germany, the uk, Austria and elsewhere.” Although Singh is disappointed that most Malaysians have no idea about this growing acclaim, the Malaysian composers collective recently issued a cd with pieces by 10 of its members to give their recordings wider exposure.

ne member of the group, Johan Othman, 42, is a Yale-trained lecturer now teaching music and composition at the Universiti Sains Malaysia in Penang. A Muslim Malay, Othman taps into Penang’s cultural smorgasbord for his work: He’s premiered an opera based on a 12th-century classic of Persian literature, “The Conference of the Birds,” by the poet Attar, which was sung in English by ethnic Indian and Chinese performers. Other compositions have been inspired by Chinese opera and Hindu mythology. His next opera, as yet untitled, is based on the Hindu epic “The Ramayana.”

ne member of the group, Johan Othman, 42, is a Yale-trained lecturer now teaching music and composition at the Universiti Sains Malaysia in Penang. A Muslim Malay, Othman taps into Penang’s cultural smorgasbord for his work: He’s premiered an opera based on a 12th-century classic of Persian literature, “The Conference of the Birds,” by the poet Attar, which was sung in English by ethnic Indian and Chinese performers. Other compositions have been inspired by Chinese opera and Hindu mythology. His next opera, as yet untitled, is based on the Hindu epic “The Ramayana.”

Drinking tea at Penang’s venerable E&O Hotel, as distant ships steam along the Strait of Melaka, the world’s busiest sea lane, Othman talks about the government’s misguided campaign to erase rather than embrace ethnic differences, and how it affects his role as a composer. “There’s no such thing as an overall Malaysian identity, in music or anything else,” he protests. “There are several identities, and each one possesses its own exceptional character.

“I see Malaysia as more like a salad than a melting pot,” he continues, chuckling at the image. “You recognize the lettuce, tomato and all the varied ingredients. They’re not blended, but separate.”

Penang wears its ethnic and religious diversity like a badge. Residents delight in pointing out that Jalan Masjid Kapitan Keling, the half-mile-long thoroughfare in the center of the historic district, is known as the Street of Harmony because it boasts two mosques, a Hindu temple, several Chinese temples and clanhouses and an Anglican church; a Roman Catholic church is nearby.

“We’re more than just Malay, Chinese and Indian,” declares Joe Sidek, organizer of the annual July arts festival. “We are also Burmese, Armenian, Thai, Gujarati and European. Penang has been cosmopolitan since the 17th century, and there has never been any segregation here,” he insists.

|

Off the west coast of peninsular Malaysia, Penang island “has been cosmopolitan since the 17th century,” says Joe Sidek, a local businessman and volunteer arts festival organizer. Off the west coast of peninsular Malaysia, Penang island “has been cosmopolitan since the 17th century,” says Joe Sidek, a local businessman and volunteer arts festival organizer. |

For the past dozen years, an arts educator named Janet Pillai has been running an eye-opening initiative that allows kids aged 10 to 16 to dig into this plenitude of interdependent commun-ities and to stage performances based on the traditions, oral histories, architecture, music, legends and crafts that they uncover within them. Over the course of six to eight months, groups of some 30 students probe the people and history of a Penang neighborhood. Making an analogy to the growth of a tree, Pillai sums up the half-anthropological, half-theatrical adventure as “a kind of academic journey to put out some fine roots and suck some of the water from the community.” I am conversing with Pillai in a tiny heritage center she’s established in an annex of the resplendent Khoo Kongsi, a 1906 Chinese clanhouse complex with an upswept temple roof, brightly painted porcelain dragons, carved gilt ornamentation and lion statues guarding the courtyard.

For the first four months of Pillai’s projects, the kids conduct research—recording spoken recollections in Malay, English and Chinese with a historian, gathering songs, music and ambient sound from the environment with a sound engineer, examining vernacular buildings with an architect, and experimenting with puppet-making with a traditional puppeteer and woodcarving with a master craftsman. After the research phase, they assemble a production—writing the text, composing music and lyrics based on the oral memoirs, constructing sets, designing costumes. Finally, they put on a number of performances for the communities, reflecting their cultures back to them and reinforcing the children’s links with their own backgrounds.

“What’s interesting is how the students contemporize traditions,” observes Pillai. They turn ancient legends into comic books or video games, for instance, or offer up paper iPads along with fake 500,000-ringgit bills among other gifts to be ritually burned to placate spirits during the Hungry Ghost festival. Pillai has helped drum up interest in children’s theater around the region, and similar programs are now under way in Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Across from Pillai’s office on Cannon Street, I stop off for a soft drink with Narelle McMurtrie in her café/crafts-shop/art gallery. Since migrating to Malaysia from Sydney some 26 years ago, the energetic Australian has renovated several shophouses into tourist apartments and opened two luxury hotels on Langkawi Island, a half-hour flight from Penang. Most of the hotels’ profits go to finance an animal shelter McMurtrie founded on the island in 2004, and revenues from the Penang operations fund residencies for artists.

Unlike much of KL, Penang is walkable city, and this is a considerable boon for galleries, shops and architecture enthusiasts, reckons McMurtrie. “Thanks in part to its designation as a World Heritage Site, Penang is really starting to take off in the arts,” she adds. “Young people are looking into all sorts of outlets for their creativity.”

|

A unesco World Heritage Site since 2008, George Town, on Penang, is fast becoming a vibrant center for the mixing of contemporary arts and traditional cultures of Malaysia. A unesco World Heritage Site since 2008, George Town, on Penang, is fast becoming a vibrant center for the mixing of contemporary arts and traditional cultures of Malaysia. |

Later the same evening, that creativity gets a phantasmagoric outing at a rehearsal for “River Project,” an outdoor play and part of the July arts festival that is staged alongside the infamously polluted Prangin Canal. Accompanied by lawyer and arts activist Lee Khai, my indispensable guide to the cultural life of Penang, I stand gape-mouthed with amazement as an egg-shaped creature enveloped in plastic bottles, lit by strands of colored lights, scuttles across the ground. A woman extracts herself from this illuminated chrysalis and then drags the bottles behind her as singers lament the choking off of the canal. Other actors execute gymnastic stunts around them and then move into a covered warehouse that Lee tells me was a seafood-and-produce market abandoned a decade ago. “The city has yet to figure out what to do with it,” he grouses, shaking his head in frustration. Meanwhile, the acrobats become market sellers, melodically calling out prices for their produce to evoke a bygone era. Where life and commerce once thrived now sits an empty ruin, intones one.

The actors lead the audience back outside to witness a performer clutching the canal wall a foot above the smelly muck as he painstakingly inches his way along a narrow ledge like an alpinist. I can’t bear to look... but I do. Above the madman, an actress declaims with seething indignation: “How long after the arteries are clogged can the heart of an island survive?” At last, a musician puts a long digeridoo made of pvc pipe to his lips, blowing a haunting lament to close the spectacle.

Lee reads my thoughts. “Okay, it’s agitprop, not Shakespeare, but the impulse behind the piece is very important,” he argues passionately after the performance. “We need to call attention to this pollution. The situation is truly desperate,” he urges. “Sometimes art has to be political to get change done.”

|

In addition to contributing regularly to Saudi Aramco World, Paris-based Richard Covington (richardpeacecovington@gmail.com) writes about culture, history, science and art for Smithsonian, The International Herald Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and The Sunday Times of London.

|

|

Jimin Lai (www.jiminlai.com) has been a photojournalist for nearly two decades, much of which was spent traveling throughout Asia for Reuters and Agence France-Presse covering conflicts, politics, sports and daily life. He lives in Kuala Lumpur, where he shoots for editorial, corporate and private clients. |