|

| Written by Caroline Stone |

|

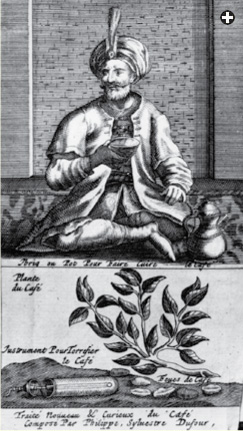

| Bridgman Art Library |

| A French illustration published in 1693 shows coffee-drinking from a bowl and an ibrik for brewing coffee, as well as a branch of a coffee tree, beans and a cylindrical ‘instrument for roasting the coffee.’ |

Coffee, native to Ethiopia, was probably drunk there long before there were written records of it, both as a tea-like drink, al-qahwa al-qishriya, made from the husks of the coffee bean, and as brewed coffee made from the beans themselves, called al-qahwa al-bunniya. The beans were also often simply chewed. But the 16th-century jurist al-Jaziri says that coffee was first used in Yemen, across the Red Sea from Ethiopia, to enable the pious to remain alert during nighttime prayers. Surely it was no less valuable for ordinary working people, much as it is today, and its use spread across the Arabian Peninsula.

s it spread, there was much discussion about the new drink—whether or not it was, in religious terms, permitted, whether it should be considered “mind-altering,” and whether it was good or bad for the health. Serious moves to prohibit the drink began in Makkah in 1511, and recurred throughout the centuries. In response, both religious and medical scholars set pen to paper in coffee’s defense. Although the literature that these debates generated tells us little about the places where coffee was drunk, it is clear from these and other sources that coffee shops were numerous from early times. Interestingly, many of the arguments made in Arabia about both coffee and coffee houses were to be repeated almost word-for-word in the West a century later, and indeed the medical debate about coffee continues globally to this day.

s it spread, there was much discussion about the new drink—whether or not it was, in religious terms, permitted, whether it should be considered “mind-altering,” and whether it was good or bad for the health. Serious moves to prohibit the drink began in Makkah in 1511, and recurred throughout the centuries. In response, both religious and medical scholars set pen to paper in coffee’s defense. Although the literature that these debates generated tells us little about the places where coffee was drunk, it is clear from these and other sources that coffee shops were numerous from early times. Interestingly, many of the arguments made in Arabia about both coffee and coffee houses were to be repeated almost word-for-word in the West a century later, and indeed the medical debate about coffee continues globally to this day.

|

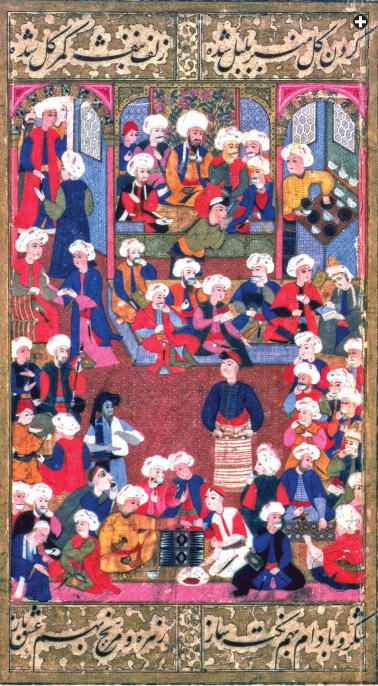

| Chester Beatty Library / Bridgeman Art Library |

| This banquet scene, from a 16th- or 17th-century Turkish album of miniatures and calligraphy, shows men drinking coffee and playing backgammon. |

Perhaps one reason for the rapid spread of coffee shops, beyond simply a taste for coffee, is that the preparation of coffee is somewhat complicated, since the beans need to be roasted and ground. Coffee shops offered the product ready-made by an experienced hand.

Writing in about 1530, Ibn ‘Abd al-Ghaffar notes that, by the beginning of the 1500’s, there were many coffee shops in cities, especially near the Great Mosque in Makkah and the central mosque of al-Azhar in Cairo. This is an early direct mention of coffee houses, though earlier juridic decisions imply their existence. Fifty years later, in his Umdat al-Safwa fi Hill al-Qahwa (The Best Defense for the Legitimacy of Coffee), al-Jaziri mentions, as if it were something unusual, that the people of Madinah preferred to drink their coffee at home. He describes coffee as having spread rapidly once it left Yemen, first being drunk publicly by the fuqaha, or scholars, teachers and students, but soon being adopted by large numbers of people. He also tells us that, although terra-cotta bowls were standard, in the Red Sea port of Jiddah coffee drinkers used porcelain from China. Unfortunately, neither writer actually describes the coffee shops and their owners, although we do learn that, when a woman who was running one in Makkah was ordered to close down, she appealed, citing poverty, and was told she might continue running it provided she veil, which she did.

The absence of complaints against coffee shops on grounds of excessive luxury or extravagance makes it safe to infer that, in all likelihood, these early coffee shops were of a simple type still found throughout the Middle East. As coffee drinking spread from the Hijaz in the western Arabian Peninsula northward to Syria, however, this changed. There, a fine coffee house became an important element of urban planning for governors who wished to emphasize their wealth and power. Every mahallah, or city ward, it seemed, soon had at least one, and they were a key component when a new market was built. In Cairo, in the 17th century, it was noted that the coffee house was the first building to be completed in any of the new upmarket housing developments along the Nile.

|

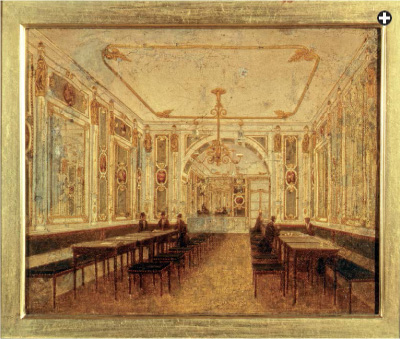

he taste for coffee and coffee houses spread westward, but not along the paths one might expect. English merchants to the Levant had developed a taste for the drink, and the earliest recorded coffee houses were set up shortly after 1650 either in London or at Oxford—the latter one is still there today. Just as in the Muslim world, coffee houses were to have a profound social impact. Seating was often at long tables with benches or chairs on either side, providing an opportunity for general conversation and a breaking down of social divisions, since it was traditional to take the next vacant seat. (Pubs did not lend themselves to mingling across class boundaries, nor to quiet discussion.) he taste for coffee and coffee houses spread westward, but not along the paths one might expect. English merchants to the Levant had developed a taste for the drink, and the earliest recorded coffee houses were set up shortly after 1650 either in London or at Oxford—the latter one is still there today. Just as in the Muslim world, coffee houses were to have a profound social impact. Seating was often at long tables with benches or chairs on either side, providing an opportunity for general conversation and a breaking down of social divisions, since it was traditional to take the next vacant seat. (Pubs did not lend themselves to mingling across class boundaries, nor to quiet discussion.)

Coffee houses were sometimes known as “penny universities” because, in the early days, for one penny anyone could come in, read the papers and listen to the conversation, as well as hear lectures often given by the most eminent men in their field. This provided ongoing educational opportunities for those who traditionally would have had little access to information. The diarist Samuel Pepys mentions literally hundreds of visits to coffee houses, both to gather news useful to his position at the Admiralty and to meet with the prominent men of his day, particularly scientists and scholars.

Other coffee houses, such as Jonathan’s in London’s Change Alley, were of the greatest importance to the business community and were closely associated with what came to be known as the London Stock Exchange. Similarly, Lloyd’s of London began as a coffee house, founded in 1668, that particularly attracted the seagoing merchant community.

More widely throughout Europe, coffee houses were almost always established by entrepreneurs from the Levant, generally Armenians or Syrians. Although it might seem logical for the earliest ones to have been in the cities with the closest trade connections to the Middle East—Venice, for example—in fact this was not the case. Coffee houses seem to have spread first in northern Europe, especially to ports with English merchant colonies, such as Bremen in 1669. In 1670 the first coffee house in the Americas opened in Boston; as in London, it was close to the commercial center and initially frequented primarily by merchants and bankers. The same was true in New York, where the somewhat later Merchants’ Coffee House helped the business community gather along Wall Street.

English and American coffee houses tended to be utilitarian, rather than glamorous like the grand ones in major Middle Eastern cities. In continental Europe, however, the development was somewhat different. Although the first coffee shops in Paris, established by Armenians, were basic places where “gentlemen and people of fashion were ashamed to go in,” this changed when an Italian set up a coffee house much closer to the Ottoman or Syrian pattern, with “tapestry, large peers of glass [mirrors], pictures, marble tables, branches for candles.” This was the Café Procope, which still survives today as a restaurant. The success of this model led to imitation by many continental café owners.

There was yet another difference between the Middle Eastern and the European and American coffee shops. The former were strictly male preserves where little was served besides coffee and tea. Because establishments that served drinks only—even only tea and coffee—were taxed more heavily than places that served food, western European cafés tended to serve food as well. This meant that, although they were equally important as meeting places and exchanges, they had a somewhat different flavor from the traditional coffee house.

In Venice, the first known coffee shop opened on the Piazza San Marco in 1683, although as early as 1575 a Muslim merchant who had been murdered in the city was recorded as having coffee-making equipment among his possessions. The Venetians shared the same doubts about coffee houses as the rulers of Egypt, the Ottoman Empire and indeed England, as a work describing the government of Venice makes clear:

It is in conformity to this Advice, that the Venetians do not allow of any Coffee houses in their City, that are able to contain great numbers of people. Their Coffee houses are generally little shops, that will not hold above five or six Persons, and there are not Seats for above two or three. So that the Company having no where to rest themselves are gone as soon as they have made an end of drinking their coffee.

Nevertheless, prohibition was as unsuccessful in Venice as elsewhere: Florian’s on Piazza San Marco, still one of the most famous cafés in the world, opened a few years later, in 1720. It was the first coffee house in Europe to allow women, which probably reassured the authorities that it was an unlikely locus for seditious political debate.

The first coffee house in Vienna opened shortly after the Ottoman siege of 1683. Various stories recount that the beans were left behind by the Turkish troops (and that croissants were invented as a mockery of the Turkish crescent), but they cannot be substantiated. The owner of the coffee house seems to have been either Greek or Armenian, and certainly Vienna, like much of Ottoman-influenced Central Europe, was one of the places where the coffee house became most culturally important. |

All this had consequences: Coffee beans became an important item of trade, of course, but—much more important—the spread of coffee shops revolutionized social intercourse, first in the Muslim world and then in the West.

Before the advent of the coffee shop, it was often difficult to find a public place to meet and talk with one’s friends. The outdoors, for much of the year, was too hot or too cold. Islamic custom insisted on the privacy of the home and, for all but the rich, it was difficult for a man to entertain a visitor without forcing the women of the house to remain secluded, in perhaps the only other room.

|

| Medeo Preziosi / Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman Art Library |

| This 1854 watercolor coffee-house scene from Istanbul shows the informality of seating that made the coffee house a place where men of diverse occupations and classes could mingle. The artist, Amede Preziosi, was born in Malta and lived in Istanbul for some 40 years. |

Nor was there a custom of eating away from home, except when traveling, so there were no restaurants to provide neutral, public meeting grounds. The traditional gathering place was, of course, the mosque, but there a certain restraint was demanded: It was hardly a place for a group of young men, for example, to relax and spend a lighthearted evening, or for that matter, for men of different faiths to discuss a business venture. Another possibility would have been the hammam, or bath house, but that was apparently not the right atmosphere for serious debate or discussion.

Coffee shops changed all that. They provided a place, neither home nor work, where people could meet and talk more freely than anywhere else, widen their social circle, make new contacts and learn what was going on in the world from points of view they might not otherwise encounter. The numerous western accounts of coffee shops—which initially fascinated travelers—are unclear as to who exactly patronized them, and probably it varied much from place to place and period to period. It is likely that the smaller neighborhood coffee shops had a relatively homogeneous, local clientele, or possibly served members of a particular guild, ethnic group or work affiliation; the great coffee houses, such as those along the waterfront in Istanbul, offered cosmopolitan meeting places for a wide variety of people. The French traveler Jean de Thévenot, writing in the mid-17th century, may have exaggerated, but there was a measure of truth in his observation that, especially in major cities, “all sorts of people come to these places, without distinction of religion or social position; there is not the slightest bit of shame in entering such a place, and many go there simply to chat with one another.”

|

| Anonymous / Erich Lessing / Art Resource |

| This painting dated 1856 shows a coffee house in Antalya, Turkey, set along water—much as outdoor cafes are today. |

There was also a further element in the allure of coffee houses, beyond a stimulating and flavorful drink, agreeable surroundings and companionship: In the coffee shop, patrons were to various extents freed from the rigid protocols of their times. The physical layout that became most common was a single large room with cushioned benches running around the walls—individual tables and chairs were a much later, western development—and in the grander coffee houses there would be a fountain in the center. Conversation, then, was never very private, and could easily become general, perhaps turning into a debate on a topic of broad interest; written sources mention informal seminars in coffee shops, and even sermons by wandering preachers. Besides this, apart from the dais in grander establishments, which was reserved for the most distinguished visitors, patrons were customarily seated in the order of their arrival, and not according to rank or wealth. This made for a very exciting sense of freedom from social constraints, and it gave society an entirely new dimension for what today we call “social networking.”

Then there was the matter of entertainment. Numerous authors have described the attractions that coffee houses provided, a major one being storytellers, particularly during the nights of the holy month of Ramadan. (Today they are rare, having been displaced by television serials.) Earlier writers also mention music as a pleasure of the coffee house, while European travelers in Cairo and Syria speak somewhat unenthusiastically of shadow-puppet shows.

|

offee drinking was not reserved to the cities. Simple coffee shops were to be found in villages, and indeed anywhere that there were sufficient passers-by. The mathematician Carsten Niebuhr, traveling in the Arabian Peninsula in the 1760’s, describes a coffee shop on the road to Bayt al-Faqih, now in Yemen: offee drinking was not reserved to the cities. Simple coffee shops were to be found in villages, and indeed anywhere that there were sufficient passers-by. The mathematician Carsten Niebuhr, traveling in the Arabian Peninsula in the 1760’s, describes a coffee shop on the road to Bayt al-Faqih, now in Yemen:

We rested in a coffee-shop situated near a village. Mokeya is the name given by the Arabs to such coffee-houses which stand in the open country, and are intended, like our inns, for the accommodation of travelers. They are mere huts, and are scarcely furnished with a Serir, or a long seat of straw ropes; nor do they afford any refreshment but Kischer, a hot infusion of coffee-beans. This drink is served out in coarse earthenware cups; but persons of distinction carry always porcelain cups in their baggage. Fresh water is distributed gratis. The master of the coffee-house lives commonly in some neighboring village, whence he comes every day to wait for passengers.

Simple coffee houses of this type are still found along roads from North Africa to—until recently—Afghanistan, whereas in Iran, tea has largely taken the place of coffee. These rural coffee- and/or tea houses catered to a passing clientele, rather than serving as centers of village life. Until the late 20th century, they might be decorated with paintings. Often, there were symbols of hospitality: a tea- or coffee pot; a cut melon; a water-pipe; a bunch of flowers. Where a storyteller performed, the attributes of the hero of his tales might be painted: his sword or gun, his horse or perhaps the scene of some of his adventures. Sometimes landscapes would show national monuments, or there might be entirely fanciful motifs.

Many travelers comment on the preference for siting coffee houses near water: Thévenot, so often positive in his impressions, remarks that ‘all the cafés of Damascus are beautiful—lots of fountains, nearby rivers, tree-shaded spots, roses and other flowers; a cool, refreshing and pleasant spot.’

The Portuguese traveler Pedro Texeira in 1604 describes drinking coffee from Chinese porcelain cups in Baghdad: “These places are chiefly frequented at night in summer, and by day in winter. This house is near the river, over which it has many windows, and two galleries, making it a very pleasant resort. There are others like it in the city, and many more throughout Turkey and Persia.”

|

| Courtesy of Caroline Stone |

| Also from a late 19th-century French postcard set is this photograph of a rural coffee house in Morocco. |

This was true also of rural coffee houses. Swedish historian and diplomat Abraham d’Ohsson, writing in the late 18th century, tells us that “in the countryside, they are shaded by great trees and trellises of vines, with large benches on the outside.”

Across the Ottoman Empire in particular, where they were the center of secular village life, there was a preference for setting coffee houses beside a spring. Generally the little kiosk stood in the shade of a vast and ancient tree, often a plane, which had been carefully pruned and the branches skillfully grafted together to provide a wonderful canopy of shade. At the small town of Libohovë, near the World Heritage site of Gjirokastër in Albania, a great tree standing by a little stream is recorded as having shaded a coffee house for nearly 400 years and is itself even older—perhaps, they say, the oldest in the Balkans. |

As businesses, coffee houses were often excellent investments. Some of the most elaborate and beautiful ones, particularly in Istanbul, were built by the Janissaries, who employed famous architects; an example is an internationally known establishment on the waterfront at Çardak Iskelesi. These then also served as clubhouses for a particular orta, or battalion, and later they provided income when official financing for the Janissaries was reduced.

The Ottoman historian Ibrahim-i Peçevi, writing in about 1635, describes the spread of coffee houses throughout the Ottoman world from the middle of the 16th century, with special reference to Istanbul. Like many writers, he expresses mixed feelings about them, but it is hard not to feel that the comments say more about the writer, or perhaps his individual experience, than the subject. Whereas Thévenot takes a positive view of both coffee and coffee houses, commenting that “French merchants, when they have a lot of letters to write and want to work all through the night, take a cup or two of coffee in the evening,” the Venetian bailo, or permanent representative at Istanbul, Gianfrancesco Morosini, writing in 1585, takes a rather jaundiced view:

All these people are quite base, of low costume and very little industry.... They continually sit about, and for entertainment they are in the habit of drinking, in public, in shops and in the streets, a black liquid, ...[as hot] as they can stand it, which is extracted from a seed they call Caveé.... It is said to have the property of keeping a man awake.

And whereas Ottoman writer Evliya Çelebi’s opinion was generally favorable, Mustafa ‘Ali Çelebi, a historian, was harsh in describing Cairo in 1599: “Some coffee houses are full of madmen, in spite of the fact there are perfectly good lunatic asylums.”

|

| MUSEO DI MILANO / SCALA / ART RESOURCE |

| In Milan, the grand Caffé degli Specchi took on a seating arrangement not unlike Turkish establishments, but with the addition of tables and chairs. |

With the passing of time, the debate of the fuqaha in the East and the Catholic Church in the West as to whether or not coffee was religiously permissible gave way to a social and political concern that was also expressed in almost identical terms in both East and West: that coffee shops were encouraging men—especially young men—to waste time when they should be working, and that the mixing of different classes and the freedom of debate found in coffee houses would foment discontent and disruption of the social order.

This concern was particularly acute in the Ottoman Empire, where rioting by disaffected Janissaries was a perennial problem. The English ambassador Sir Thomas Roe, writing in 1623, makes the point that the general perception was completely wrong, and that in fact all was quite well as long as the Janissaries were merely “muttering and grumbling in the coffee houses”; danger, he maintains, came only when they fell silent. He was quite correct, but this was not how the situation was perceived by the authorities: Repeated efforts were made to close coffee houses across the Muslim world, and in the 1630’s, Murad iv ordered them not only closed but razed.

|

offee also traveled east. In Iran, in particular, it seems to have quickly become less controversial than elsewhere. offee also traveled east. In Iran, in particular, it seems to have quickly become less controversial than elsewhere.

The first mention of coffee in Iran comes in the work of the doctor Imad al-Din Mahmud al-Shirazi, in the mid-16th century, and his interest in it is largely medical. Yet as early as 1602, an Austrian envoy to the court mentions something that sounds like coffee, and coffee soon became part of hospitality at the Safavid court. The Spanish envoy Don Garcia de Silva y Figueroa, writing in 1619, mentions Shah Abbas visiting the coffee houses of Isfahan, as do Pietro della Valle and the Russian traveler Fedot Kotov—testimony to the social acceptability of the institution.

Further evidence comes from records showing that Iran imported coffee in large quantities through the Dutch, and the mention in records from 1634 of a shipment of 5000 loads of small Chinese coffee cups, intended for sale in Iran, gives an idea of how popular the drink had become by that early time.

Jean Chardin, writing his account of travels in Persia “and other places in the East” in 1686, describes Iranian coffee houses this way:

These houses, which are big spacious and elevated halls, of various shapes, are generally the most beautiful places in the cities, since these are the locales where the locals meet and seek entertainment. Several of them, especially those in the big cities, have a water basin in the middle. Around the room are platforms, which are about three feet high and approximately three to four feet wide, more or less according to the size of the location...They open in the early morning and it is then as well as in the evening that they are most crowded.

|

In England, King Charles ii expressed essentially the same view in his 1675 “Proclamation for the Suppression of Coffee Houses,” which states that they were “the great resort of idle and disaffected persons [which] ... have produced very evil and dangerous effects [and] … divers false rumours.... Malicious and Scandalous Reports are devised and spread abroad, to the Defamation of the Peace and Quiet of the Realm.”

Prohibition did no good for either ruler. Far too many respectable people—qadis and lawyers, scholars and students, merchants and clerks—wanted not only a cup of coffee, which Europeans, at least, considered secondary, but a space in which to meet and talk, an extension of often cramped housing, a way to offer inexpensive entertainment to friends and a place to relax that was both public and familiar. Charles ii’s ban came to naught; Murad iv’s resulted in coffee-house culture transferring to Bursa, some 90 kilometers (56 mi) away. The soldier and scholar Kâtip Çelebi, writing in about 1640, describes the process; ironically, he himself died suddenly and peacefully while drinking a cup of coffee.

|

| Medeo Preziosi / Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman Art Library |

| Coffee houses became popular in England around 1650. This London establishment, above, was depicted by an

anonymous artist probably in the late 1600’s. |

|

| Museum of London / Art Archive / Art Resource |

| Because small coins were often scarce, many coffee houses issued tokens such as this one. |

Over and over again, travelers commented on the hundreds—and in great cities such as Cairo they asserted there were thousands—of coffee houses and coffee shops, and even smaller towns in the provinces were well supplied. Evliya Çelebi, writing in his Seyahatname in 1670, always enumerates the coffee houses as well as other buildings of note. In A Journey to Berat and Elbasan, he says, for example, of Berat (now in Albania):

In the vicinity of this bazaar there are six coffee houses, each one painted and decorated like a Chinese idol temple. A few of them are on the bank of the ... river which flows through the city. Here some people bathe in the water, some come to fish and others gather to converse with their friends on matters both religious and secular. There are many poets, scholars and writers here possessing vast knowledge. They are polite and elegant, intelligent and mature, and given more to carousing than to piety.

The esthetic he refers to is another fascinating aspect of the grander coffee houses. In Istanbul, Damascus and Cairo, as elsewhere, particular coffee houses often had a particular “flavor.” Fishawy’s, said to be Nobel Prize–winner Naguib Mahfouz’s favorite café and a treasured meeting place of poets and writers, has retained much in the way of traditional furniture and arabesque decoration, as has the Zahret al-Bustan, now more popular, however, with tourists than intellectuals.

In contrast, the M’Rabet in the madinah of Tunis is the exact opposite of the grandiose interiors that have been mentioned. Absolutely simple, whitewashed, with columns painted in red and green and along the walls masonry divans covered with matting, it has an atmosphere of tranquility, and the place seems to take one back to the very origins of coffee drinking, and the coffee house, in the Arabian Peninsula.

|

Caroline Stone (stonelunde@hotmail.com) divides her time between Cambridge and Seville. Her latest book, Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness, translated with Paul Lunde from the medieval Arab accounts of the lands in the Far North, was published in 2011 by Penguin Classics. |