|

Fifty-two years ago, as Soviet cosmonauts and us

astronauts were first venturing into space, another

space program was also taking off—in Lebanon. |

Yes, in the early 1960’s, the country of 1.8 million people, one-quarter the size of Switzerland, was launching research rockets that reached altitudes high enough to get the attention of the Cold War superpowers.

Yes, in the early 1960’s, the country of 1.8 million people, one-quarter the size of Switzerland, was launching research rockets that reached altitudes high enough to get the attention of the Cold War superpowers.

But the Lebanese program was more about attitude than altitude: Neither a government nor a military effort, this was a science club project founded by a first-year college instructor and his undergraduate students. And while post-Sputnik amateur rocketry was on the rise, mostly in the us, no amateurs anywhere won more public acclaim than the ones in Lebanon.

|

| MAnoUgIAn CoLLeCTIon |

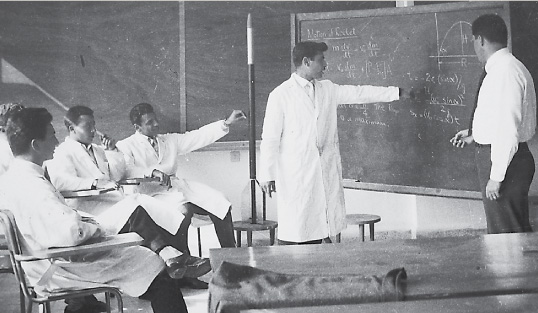

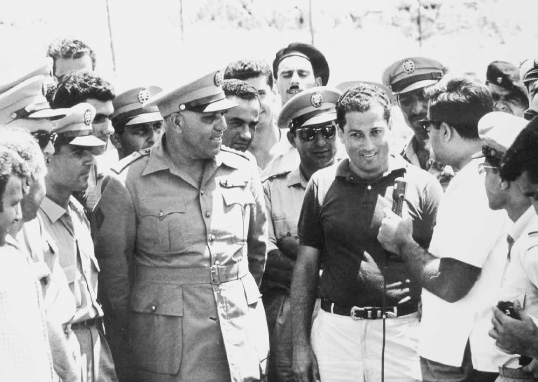

| Manoug Manougian, right, with members of the Haigazian College Rocket Society, which he founded in 1960. It later became the Lebanese Rocket Society. |

But that is forgotten history now, says Manoug Manougian, now 77 and a mathematics professor at the University of Southern Florida in Tampa. He leads me into a conference room where he has set out on a table file boxes filled with half-century-old newspapers, photographs and 16mm film reels.

“When I decided to leave, no one was interested to take care of all this,” says Manougian. “But I felt, even at that point, that it was a part of Lebanese history.”

|

| Top: MAnoUgIAn CoLLeCTIon |

| Above: Manougian now teaches at the University of Southern Florida, where he keeps newspaper front pages on his office wall. “It was a part of Lebanese history,” he says. Top: The Society launched its first “tiny baby rockets” at the mountain farm of one of its members. |

Born in the Old City of Jerusalem, Manougian won a scholarship to the University of Texas, and he graduated in 1960 with a major in math. Right away, Haigazian College in Beirut was glad to offer him a job teaching both math and physics. The college also made him the faculty advisor for the science club, which Manougian reoriented by putting up a recruitment sign that asked, “Do you want to be part of the Haigazian College Rocket Society?”

He did this, he explains, because even as a boy, he loved the idea of rockets. He recalls taking penknife in hand and carving into his desk images of rocket ships flying to the moon. “It’s the kind of thing that stays with you,” Manougian says.

John Markarian, former head of the college, now 95, recalls thinking it was “a rather harmless student activity. What a wonderful thing it was.” The first rocket, he says, “was the size of a pencil.”

Six students signed up, and in November 1960, the Haigazian College Rocket Society (hcrs) was born. “It is not a matter of just putting propellant in the tube and lighting it,” says Manougian. Former hcrs member Garo Basmadjian explains that at the time, “we didn’t have much knowledge, so we looked at ways to increase the thrust of the rocket by using certain chemicals.” After dismissing gunpowder, they settled on sulfur and zinc powders. Then they would pile into Manougian’s aging Oldsmobile and head to the family farm of fellow student Hrair Kelechian, in the mountains, where they would try to get their aluminum tubes to do, well, anything.

“We had a lot of failures, really,” says Basmadjian.

|

| MAnoUgIAn CoLLeCTIoN |

| 1963 saw the launch of Cedar 3, a three-stage rocket that allegedly broadcast "Long Live Lebanon" from its nose cone as it rose. Left: The Cedar launches were commemorated on this postage stamp issued on Lebanon's independence day. |

|

| Manougian Collection |

But soon enough “it did fly some distance,” Manougian adds.

The hcrs began using a pine-forested mountain northeast of Beirut to shoot off the “tiny baby rockets,” as Manougian calls them, each no longer than half a meter (19").

As they experimented, the rockets grew larger. By April 1961, two months after the first manned Soviet orbital mission, the college’s entire student body of 200 drove up for the launch of a rocket that was more than a meter long (40").

The launch tube aimed the rocket across an unpopulated valley, but at ignition, Manougian recalls, the thrust pushed the “very primitive” launcher backward, in the opposite direction, and instead of arcing up across the valley, the rocket blazed up the mountain behind the students.

|

| MAnoUgIAn CoLLeCTIon |

| Launches at the military site of Dbayea, overlooking the Mediterranean north of Beirut, drew crowds of spectators, journalists and photographers. |

“We had no idea what lay in that direction,” says Manougian. To investigate, the students started climbing, and on arrival at the Greek Orthodox church on the peak, they came on puzzled priests staring at the remains of the rocket, which had impacted the earth just short of the church’s great oaken doors. Manougian calculated that, even with the unplanned launch angle, considering thrust and landing point, the rocket had reached an altitude of about a kilometer (3300'), and he adds the bold claim that this was the first modern rocket launched in the Middle East.

|

| MAnoUgIAn CoLLeCTIon |

| Ballistics expert Lt. Youssef Wehbe (in uniform) began supporting the rocket society in 1961, initially by allowing it access to an artillery range on Mount Sannine. |

The next day, Manougian got a call from Lieutenant Youssef Wehbe of the Lebanese military. He cautioned that the hcrs couldn’t just go up any old mountainside and shoot off rockets. They could, however, do it as much as they wished under controlled conditions at the military’s artillery range on Mt. Sannine. Wehbe, also in his 20’s, was a ballistics expert, and he was more than intrigued. “Our first success,” says Manougian, came there at Mt. Sannine, where the rocket they demonstrated for Wehbe soared 2.3 kilometers (7400') into the air.

Newspapers got wind of the launches, and they reported that the “Cedar 2C” (named for the symbol of Lebanon) had reached 14.5 kilometers (47,500'). “Obviously, that’s not yet the moon distance of 365,000 kilometers. But the Lebanese aren’t after that, they’re after technique,” stated the report.

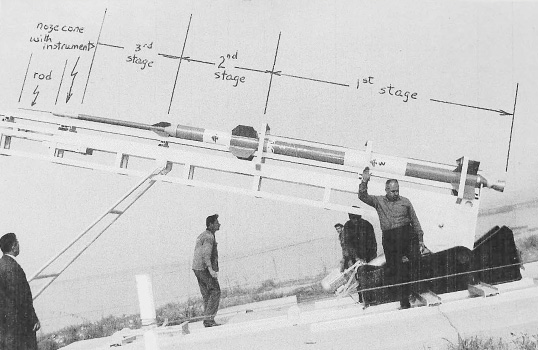

Under Wehbe’s supervision, hcrs developed two-stage and then three-stage rockets, each bigger than the last and soaring higher and farther.

In the papers, the rocket men were portrayed as both brawny and brainy, and they were the talk of Lebanon. A fan club of prominent Lebanese—mostly women—formed the Comité d’encouragement du Groupe Haigazian. In the photos and films of the launches, one can see generals deferring to college kids in hcrs hardhats and eagerly posing in the press photos with them. Even Lebanese president Fuad Chehab invited Manougian and his students to the palace for a photo op.

“We were just having fun and doing something we all wanted to do,” says Basmadjian. “When the president came into the picture and gave us some money, it took off.”

|

|

Three thousand years ago, the Phoenicians, who lived on today’s Lebanese coast but traded as far away as England, were pioneers of celestial navigation using Polaris, the North Star, recognized by other cultures as the “Phoenician star.”

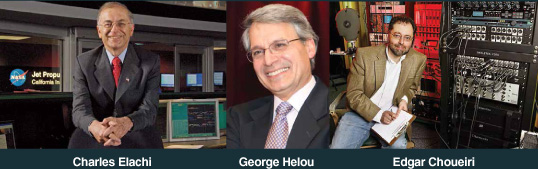

Today, natives of Lebanon are helping lead the way to the stars.

“As a child in Lebanon, I was an avid reader of books about Sinbad, Ali Baba, Ibn Battuta, Captain Cook, Magellan and Columbus, wondering how exciting it was for these explorers to anticipate what they were going to see and discover,” says Charles Elachi, who for 12 years has directed the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “I lead a team of 5000 explorers in defining objectives that seem almost impossible, then going ahead and implementing them. In the last few decades, we have visited every planet in the solar system and discovered volcanoes on Io, geysers on Enceladus, lakes on Titan and river beds on Mars.”

At Princeton University, Edgar Choueiri is director and chief scientist of the Electric Propulsion and Plasma Dynamics Laboratory. “Plasma rockets differ from chemical rockets, which were the focus of the Haigazian group and which have been the standard means for launching and propelling spacecraft into space,” he says. The rockets Choueiri is developing use magnetic fields and electrically charged gases (plasmas) to produce thrust, and they are intended for cargo and manned missions to the moon and Mars. The first toy Choueiri remembers from his childhood in Lebanon was a water-propelled rocket that he launched with his father. “It was a poetic moment for me when, decades later, I found myself working, under nasa funding, on a plasma rocket concept that uses water as propellant,” he says.

George Helou is the director of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), also in Pasadena, California, and of nasa’s Herschel Science Center. He says it was one of his teachers at the American University of Beirut, Pierre Monoud, who was also a faculty advisor to the lrs, who “encouraged me to pursue astrophysics.” Helou has provided research and management for every major infrared astronomy project launched by nasa and the European Space Agency. He researches galaxies, and in particular how they turn gas and dust into stars. “The starry nights of Lebanon’s mountains attracted me to the cosmos,” says Helou. “Astrophysics has been and still is a wonderful journey.” |

|

Left: Jet Propulsion Laboratory / California Institute of Technology;

CenTeR: CALIFoRnIA InSTITUTe oF TeCHnoLogY; RIgHT: eppdYL / pRInCeTon UnIveRSITY |

|

“We were members of a scientific society. We felt good about it,” says Simon Aprahamian, another former student. “But it didn’t feel like what the us or ussr were doing. It’s a small country, Lebanon. People felt, ‘This is something happening in our country. Let’s get involved.’”

Launches now drew hundreds of spectators to the site overlooking the Mediterranean Sea at Dbayea, north of Beirut, and Haigazian itself became known as “Rocket College.” As the hcrs was now the country’s pride, its name changed to the Lebanese Rocket Society (lrs).

|

| Above And Below: Manougian Collection |

| Cedar 4 was the society's most powerful rocket. newspapers claimed that it reached a maximum height between 145 and 200 kilometers (90–125 mi), though the reality was surely much less. For Manougian, however, the rockets and their launches were not about setting records, but about teaching future scientists. |

Lebanese weren’t the only ones watching. Both superpowers, according to Manougian, had “cultural attachés” observing the launches, and he believes they did more than that. “My papers were always out of place on my desk,” he says, and he recalls once leaving a note: “My filing cabinet I am leaving open. I have nothing to hide. But please don’t mess up my desk!”

One night in 1962, Manougian was taken in the back of a limousine to a factory in the heart of downtown Beirut. There, he was introduced to Shaykh Sabah bin Salim Al-Sabah of Kuwait, who offered to fund Manougian’s experiments generously if he moved them to Kuwait. Manougian hesitated, recalling the commitment he made to himself when he accepted the post at Haigazian: “Don’t stay too long. You only have a bachelor’s degree.” More than a private lab, Manougian wanted to get back to Texas to get his master’s.

Before Manougian left for Texas, however, he sat down with Wehbe to plan two launches for Lebanese Independence Day, November 21, in both 1963 and 1964. The rockets would be called Cedar 3 and Cedar 4, and each would have three stages. They would dwarf what went before in both size and strength: seven meters (22') long, weighing in at 1270 kilograms (2800 lbs) and capable of rising an estimated 325 kilometers (200 mi) and covering a range of nearly 1000 kilometers (about 620 mi), the rockets would generate some 23,000 kilograms (50,000 lbs) of thrust to hit a top speed of 9000 kilometers per hour (5500 mph). From the nose cone, a recording of the Lebanese national anthem would be broadcast.

|

|

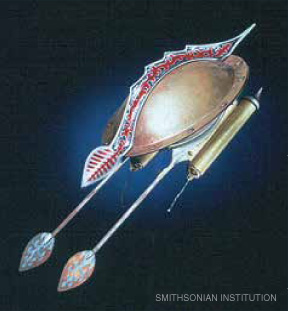

Today, historians regard it as more likely that the rocket was accidentally discovered, rather than invented, by the Chinese during the Sung Dynasty between 960 and 1279 ce. And although historians have pinpointed reports of “rockets” used in 13th-century battles, Frank H. Winter, curator emeritus of the Smithsonian Institution’s Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., sees them as isolated incidents of the use of “gunpowder-type weapons” and not necessarily rockets, which are distinguished, he says, by being self-propelled.

|

There is an intriguing manuscript, dating from between 1270 and 1280, written by a Syrian military engineer named Hasan al-Rammah. His book, Al-Furusiyya wa al-Manasib al-Harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices), describes uses for gunpowder as well as the first process for the purification of potassium nitrate, a key ingredient. He also includes 107 recipes for gunpowder and 22 recipes for rockets, which he called al-siham al-khatai (“Chinese arrows”). Al-Rammah astonishes any contemporary reader by describing and illustrating one rocket-propelled device that looks like a scarab beetle. He called it “the egg which moves itself and burns.” Comprised of two pans fastened together and filled with “naphtha, metal filings and good mixtures” (likely containing saltpeter), it had two rudders and was propelled by a large rocket. It seems to have been designed to ride on the surface of the water as a kind of torpedo.

Ahmad Yousef al-Hassan, the late scholar of Islamic technology, concluded that this book “cannot be the invention of a single person,” and thus the “al-Rammah rocket” could possibly be an even earlier invention.

Was it history’s first rocket? “This is really hard to pin down exactly,” says Winter. “Its appearance in the work of al-Rammah shows that the rocket was known in the Arab world by ... about 1280.” He adds that al-Rammah “clearly used ‘Chinese materials,’ i.e., terms and sources.” Thus, at the very least, the knowledge of gunpowder and rockets in the Eastern Mediterranean would argue for the exchange of scientific knowledge among the leading civilizations of the time.

|

|

On November 21, 1963, a model of Cedar 3 was paraded through Beirut’s streets to great applause. The cover of the souvenir booklet shows a rocket overflying the city. For Cedar 4, Lebanon issued commemorative postage stamps showing the rocket leaving Earth’s atmosphere. On launch day, 15,000 people showed up, along with generals and even the president.

|

| MAnoUgIAn CoLLeCTIon |

| In those years, Manougian recalls, the "rocket boys" were celebrities and Haigazian College was "rocket college." Above, Manougian answers a journalist's questions after a launch. The last rocket, Cedar 10, flew in 1967, after Manougian had returned to the us to earn his doctorate. Then, Cold War politics shut down the program. |

The newspapers reported with national pride that the rockets flew into “space” and landed on the far side of Cyprus. The altitudes that were published varied from 145 to 200 kilometers (90–125 mi). The actual figures, however, are likely more modest. “That was totally wishful,” says Ed Hart, the Haigazian physics professor who took over as faculty advisor to the lrs. “It never came close. We kept our mouths shut [because] it was not a student matter anymore. It had become a social, society kind of matter.”

For Manougian, Wehbe told him that according to calculations, the rockets achieved their aims. Hart, whose specialty is science education, brings it back to empirical achievement: “We were teaching students a great deal, and that is what we came for: the mystery and structure of forces.”

In 1964, master’s degree in hand, Manougian returned to Lebanon, and again collaborated with Wehbe on a few more launches. By then, world powers were interested: France supplied the rocket fuel; the us invited Wehbe to Cape Canaveral.

Cedar 8 was the last lrs rocket. Launched in 1966, it was a two-stage, 5.7-meter (18') rocket with a range of 110 kilometers (68 mi)—a long way from the pencil-sized rockets of five years earlier. “We were launching in the evening, and we put lights on top of the second stage to be able to witness the separation. There were no hitches. It took off beautifully, the separation was fairly obvious, nothing exploded and it landed at the time it was supposed to land. To me that was a perfect launch,” says Manougian, still in awe 50 years on.

|

| |

| Under Manougian's guidance, a new rocket society at usf is exploring rockets that use plasma engines. |

By 1966 Manougian grew concerned about the extent of military involvement. “I’d accomplished what I’d come there to accomplish. It was time for me to get my doctoral degree and do what I love most, which was teaching,” he says. He left in August, and the Lebanese Rocket Society was no more.

But under military auspices, a last Lebanese rocket, Cedar 10, flew in 1967. According to Manougian, Wehbe told him that French president Charles de Gaulle soon pressured President Chehab to shut down the rocket project for geopolitical reasons.

Decades of political turbulence followed, and the story of the lrs lay hidden away in Manougian’s boxes.

Two years ago, science and engineering students at the University of Southern Florida approached Manougian to set up a rocket society. “My students did this 50 years ago,” he replied, adding, “What can you do now that’s innovative?” That’s how he became faculty advisor of the Society of Aeronautics and Rocketry (soar), which is exploring rockets powered by electromagnetism and nano-materials. As in Beirut, he says, “the important thing is not the rocket. It is the scientific venture.”

“Soar” is an apt metaphor for all involved. With the hcrs/lrs rocket projects, Lebanon punched well above its weight. Wehbe retired as a brigadier general. Manougian went on to win teaching awards, and he is loved by his students now as then. Many of the lrs students, and others inspired by them, went on to excel in scientific pursuits.

“Most of us come from very humble beginnings. But we had some brains and we studied hard,” says Basmadjian.

“Did that experience help with regard to making new inventions?” asks another former student, Hampar Karageozian, who later studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and founded several ophthalmological drug companies. “Yes, it did. Because it completely changed my attitude. The attitude that we could say that nothing is impossible, we really have to think about things, we really have to try things. And it might work!”