the 200th birthday of Giuseppe Verdi, the Italian composer of one of the most popular operas of all time: Aida. Set in ancient Egypt, it has been performed in the vast Roman amphitheater of Verona, Italy; in front of the Temple of Luxor in Egypt; and in opera houses large and small throughout the world, literally thousands of times. But the path to Aida’s success was surprisingly circuitous.

the 200th birthday of Giuseppe Verdi, the Italian composer of one of the most popular operas of all time: Aida. Set in ancient Egypt, it has been performed in the vast Roman amphitheater of Verona, Italy; in front of the Temple of Luxor in Egypt; and in opera houses large and small throughout the world, literally thousands of times. But the path to Aida’s success was surprisingly circuitous.

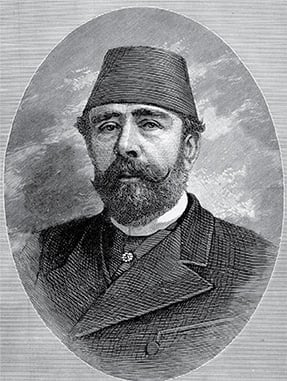

s the ruler of Egypt since 1863, Khedive Ismail was determined not to stint on the celebrations marking the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Yes, it was expensive to host a thousand official guests in style. It was certainly expensive to construct the new Gezira Palace specifically to house his most illustrious visitor, the Empress Eugénie of France. And it was incredibly expensive to build a whole new quarter of Cairo for the occasion—especially one that resembled Baron Georges Haussmann’s redesigned Paris, complete with gas-lit boulevards, landscaped gardens and Cairo’s first opera house. But the khedive believed that “my country is no longer in Africa; we are now part of Europe,” and that the Suez Canal would change the course of world history or, at the very least, the course of world trade.

s the ruler of Egypt since 1863, Khedive Ismail was determined not to stint on the celebrations marking the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Yes, it was expensive to host a thousand official guests in style. It was certainly expensive to construct the new Gezira Palace specifically to house his most illustrious visitor, the Empress Eugénie of France. And it was incredibly expensive to build a whole new quarter of Cairo for the occasion—especially one that resembled Baron Georges Haussmann’s redesigned Paris, complete with gas-lit boulevards, landscaped gardens and Cairo’s first opera house. But the khedive believed that “my country is no longer in Africa; we are now part of Europe,” and that the Suez Canal would change the course of world history or, at the very least, the course of world trade.

|

| BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| “My country is no longer in Africa; we are now part of Europe,” said Egyptian Khedive Ismail Pasha, who opened the Suez Canal, rebuilt part of Cairo and constructed an epitome of high culture: an opera house modeled on the famous La Scala of Milan, which he inaugurated in 1869 with Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi, top. Despite that honor, Verdi initially rebuffed Ismail's commission, and later, his fear of the sea kept him from attending the opening. |

So the celebrations at the opening of the canal had to be the most magnificent they could possibly be. And what could be more impressive than to commission the famous Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi, whose work reverberated throughout the world, to create a celebratory ode to mark the opening?

Alas, Verdi was less than enthusiastic. Although his reply was polite, it was also unequivocal: “I regret that I must decline this honor, because of the number of my current activities and because it is not my custom to compose occasional pieces.”

Verdi was not forgotten, however. In early November 1869, Ismail inaugurated his new opera house—decorated in crimson, white and gold—with a production of one of the composer’s most popular operas, Rigoletto. Performed by an outstanding Italian cast and featuring 61 La Scala musicians conducted by Verdi’s former pupil and close friend Emanuele Muzio, Rigoletto was a resounding success. So too was the opera house itself. Ismail’s sumptuously appointed building seemed to delight the Empress Eugénie and the other crowned heads who attended almost as much as the performance. With its gilded boxes and sparkling chandeliers, it was clearly a building fit for an empress. Or a king. Or a khedive. Or Ismail may well have wished for the premiere of the first opera ever to pay tribute to the glories of Egypt: a new grand opera composed by none other than the great Verdi himself.

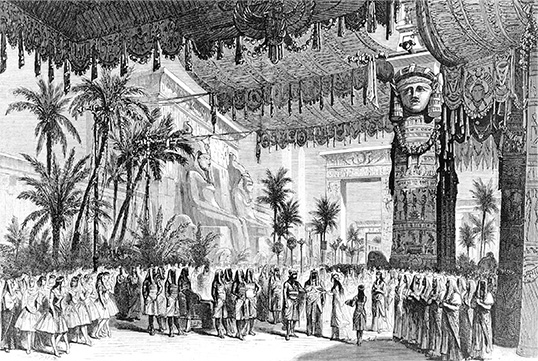

Unlikely as it seemed, Ismail’s wish would soon come true. On Christmas Eve 1871, the curtain of the Khedival Opera House rose to reveal a breathtaking scene of ancient Egypt in all its glory. Aida, the most spectacular opera of the age, premiered in Cairo.

|

| BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

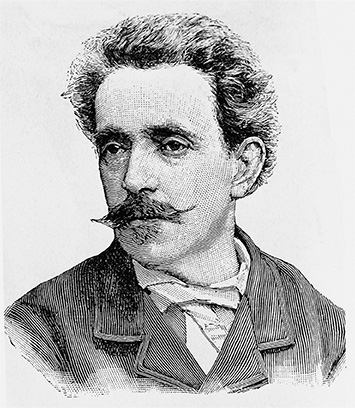

| Impressed by the story of an Ethiopian slave girl written by Auguste Mariette, above, acheologist and director of Egyptian antiquities, Verdi began to change his mind. |

How did this come about? Why did Verdi, who could not be bothered to write a mere ode, suddenly commit himself to writing a full-scale grand opera for Egypt?

There were several reasons, but the primary one was almost certainly that, in the outline of Aida, Verdi found what he valued most: a great story.

Aida had everything: the beautiful captive princess (the title role); the ambitious soldier, Radamès, who loved her; and fatefully, Aida’s father, Amonasro, who bargained that his daughter’s love of country would outweigh her love for Radamès. There was also Amneris, the powerful and jealous princess who vied with Aida for the love of Radamès—and, supporting it all, there was the incredible pomp and splendor of ancient Egypt adapted for the 19th-century stage.

To fully understand how Aida came to be, however, we must go back to 1867, when the khedive visited Paris to inaugurate the Egyptian exhibition at the Exposition Universelle. Ismail had attended the French General Staff College in Paris in the 1840’s, but the city had changed utterly since then. At the behest of Emperor Napoleon iii, Baron Haussmann, prefect of the Seine, had replaced the winding medieval alleyways with long, straight gas-lit boulevards and constructed handsome new edifices at the principal crossroads. Perhaps the most beautiful of these—certainly the most expensive—was the monumental beaux-arts Opéra Garnier. Though still under construction in 1867, the building was far enough along that its handsome façade could be seen and admired.

With the Opéra Garnier not yet completed, Parisian theatergoers continued to flock to the more familiar Opéra Le Peletier. Among them was the khedive, who, on August 19, attended a performance of Verdi’s newest opera, Don Carlos. It was a performance he would never forget. Whether it was Verdi’s powerful music, the sumptuous sets and costumes, or sympathy for a doomed young prince, Ismail suddenly became a devotee of opera, and especially of the operas of Verdi.

|

| BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

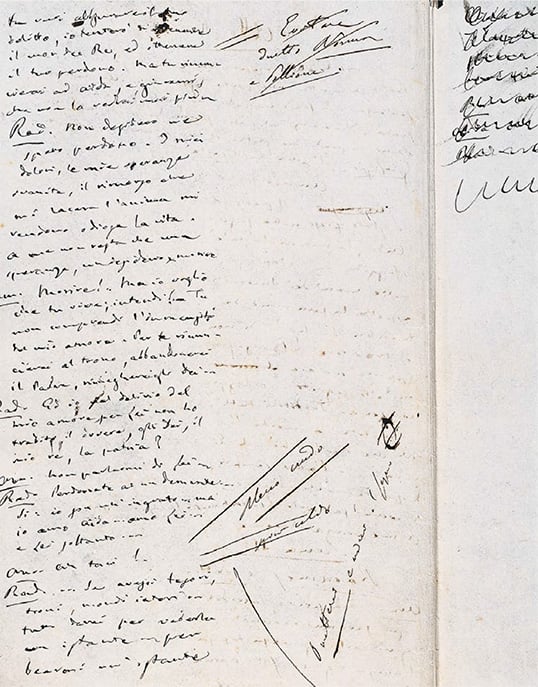

| In June 1870, Verdi and theater director Camille du Locle collaborated on the libretto, in French. This page from Act iv shows margin notes written by Verdi’s wife, Giuseppina. |

By the time the khedive returned to Cairo, his mind was spinning with plans to recreate Cairo as Haussmann had recreated Paris. He would lay out the streets in wide boulevards, and where the new quarter of Isma’ilyah met the Ezbekiya Gardens of the old quarter, he would erect the first opera house ever constructed in Egypt—or anywhere in the Middle East.

To Ismail, newly returned from Paris, an opera house represented the cultural icon of the age. Only with an opera house could Cairo hope to be counted among the great capitals of Europe. And what better than one that resembled La Scala, the great Milan edifice where so many Verdi operas had premiered?

The Italian firm of Avosani and Rossi was happy to comply, and even managed to complete the building in time to host the Empress Eugènie and others at the opening night of Rigoletto. As anticipated, the Cairo production delighted everyone who attended. No one, however, was more delighted than Ismail, who was now more determined than ever to realize his dream of an Egyptian opera.

There was but one problem. Before there could be an opera, there had to be a story.

The source could hardly have been less likely.

uguste Mariette, known as Mariette Bey in Egypt, never claimed to be a composer. Nor was he a playwright. He was the director of Egyptian antiquities, a post to which he had been appointed in 1858 after several years of outstanding work as an archeologist. As supervisor of some 35 excavations, spokesman for conservation of the monuments and keeper of the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities, he and his imagination were dominated by the glories of ancient Egypt. Mariette had even written a story about ancient Egypt—a story about an Ethiopian slave girl, an Egyptian princess and the Egyptian captain they both loved. To Mariette, and many others, the story of Aida seemed the perfect vehicle on which to base the Egyptian opera so desired by the khedive.

uguste Mariette, known as Mariette Bey in Egypt, never claimed to be a composer. Nor was he a playwright. He was the director of Egyptian antiquities, a post to which he had been appointed in 1858 after several years of outstanding work as an archeologist. As supervisor of some 35 excavations, spokesman for conservation of the monuments and keeper of the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities, he and his imagination were dominated by the glories of ancient Egypt. Mariette had even written a story about ancient Egypt—a story about an Ethiopian slave girl, an Egyptian princess and the Egyptian captain they both loved. To Mariette, and many others, the story of Aida seemed the perfect vehicle on which to base the Egyptian opera so desired by the khedive.

Whether Mariette showed his story to the French librettist and theater director Camille du Locle when he guided his friend through Egypt in 1868 is not certain. What is certain is that Mariette’s plan to adapt his story to opera form was prominent in du Locle’s mind when the librettist visited Verdi in Geneva in December 1869.

Du Locle and Verdi had collaborated with great success on Don Carlos and, hoping to work with Verdi on a new opera, du Locle often sent Verdi possible subjects to consider. That December he suggested an opera set in ancient Egypt, to be commissioned by the khedive of Egypt himself. But Verdi was involved in other projects at the time and was not interested. Nor was he interested the following March when du Locle broached the subject once again.

By this time more than a year had passed since the Cairo production of Rigoletto and Ismail was becoming anxious. It was time to begin work on his new national opera. He instructed du Locle and Mariette to wait no longer. If Verdi could not be bothered, perhaps someone else could compose it; he mentioned Charles Gounod and Richard Wagner.

Mariette quickly passed this information on to du Locle who, worried that Verdi might lose this opportunity to another composer, asked Mariette for a copy of the Aida scenario. In response, Mariette had four copies of a 23-page proposal printed and sent one to du Locle. Du Locle forwarded it to Verdi on May 14.

The idea of an opera set in ancient Egypt was one thing. An actual scenario, complete with strong characters and high drama, was another. This time Verdi was impressed.

“It is well done,” he wrote du Locle on May 26. “It offers a splendid mise-en-scène, and there are two or three situations which, if not very new, are certainly very beautiful. But who did it? There is a very expert hand in it, one accustomed to writing and one who knows the theater very well.”

|

| BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| To translate the libretto into Italian verse, Verdi turned to Antonio Ghislanzoni. |

Du Locle quickly replied that the scenario was the work of Mariette and the khedive. (In fact, certain sequences may have come from du Locle or even from Temistocle Solera, an Italian librettist employed by the khedive at that time.) But it was the drama inherent in the scenario, rather than its writers, that attracted Verdi. And on June 2 the composer finally wrote du Locle to say that Mariette’s Egyptian story would indeed be a project of interest, assuming his conditions were accepted: Verdi would have the libretto done at his own expense and, as he dreaded travel by sea, would send someone to Cairo to conduct and direct the opera in his place, again at his expense. When the score and libretto were completed, he would send a copy to the khedive, but for use only within Egypt, as the composer wished to retain the rights in all other parts of the world. Finally, Verdi requested payment of 150,000 francs, and further stipulated that he would have the right to have Aida performed at opera houses outside Egypt following the Cairo premiere.

Ten days later, du Locle received a telegram from Mariette. The khedive accepted Verdi’s terms, with one condition: The opera would have to be completed by January 1871 (only six months away), to be ready to premiere at the Khedival Opera House in February 1871.

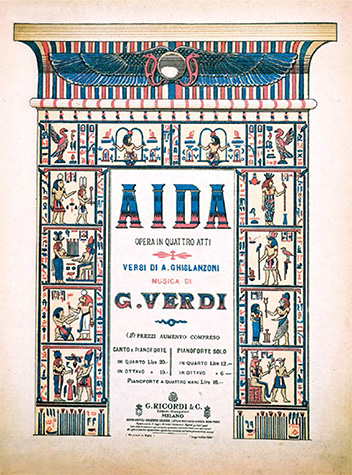

On June 19, du Locle arrived at Verdi’s home in Sant’Agata, Italy, where, for the next few days, the two men worked to create a detailed scenario in French, du Locle’s native tongue. However, as Aida was to be premiered by an Italian company at what most Egyptians came to know as “the Italian opera house,” a libretto in Italian was required. So on June 25, Verdi wrote to his music publisher and agent, Giulio Ricordi, to ask if the renowned Italian poet and librettist Antonio Ghislanzoni would be prepared to turn the French scenario into Italian verse. Shortly thereafter, Ghislanzoni, Ricordi and Verdi met at Verdi’s home to establish the scope of the work, and in mid-July Ghislanzoni sent Verdi the libretto for the first act of Aida.

Verdi was now 56 years old, a master of the opera form and a man used to having his own way. Ghislanzoni was a poet, capable of creating remarkably lyrical verse. On the whole, their different talents complemented one another. But Verdi had definite ideas about how to propel the action forward, and when he felt the poetry interfered with the dramatic moment, he was quick to say so. He was also quite capable of changing his mind—which necessarily meant changes in Ghislanzoni’s verses.

For the most part, Ghislanzoni made Verdi’s requested alterations with equanimity. He understood the composer’s working methods and respected Verdi’s judgment. But when Verdi wished to alter Radamès’ words to Aida, “No, you shall not die…You are too beautiful,” on the grounds that the soprano portraying Aida might not in fact be beautiful, Ghislanzoni objected so strongly that, for once, the poet’s phrases stood.

At the same time, Verdi bombarded du Locle with a constant stream of questions for Mariette to answer: Did the Egyptians believe in immortality? Were there priestesses of Isis or of another divinity? Please describe the ritual dances and the music that accompanied them....

As the acknowledged expert on ancient Egyptian manners and customs, Mariette was delighted to respond, but from Paris, where he had been sent by the khedive to ensure that the costumes, jewels, props and sets—all being fashioned by designers of the Paris Opera—were as authentic and spectacular as possible.

“What the viceroy [i.e., the khedive] wants,” Mariette explained to du Locle, “is a purely ancient and Egyptian opera. The sets will be based on historical accounts; the costumes will be designed after the bas-reliefs of Upper Egypt. No effort will be spared in this respect, and the mise-en-scène will be as splendid as one can imagine. You know the viceroy does things in a grand style.”

Mariette, it seemed, meant to follow the khedive’s instructions to the letter. The Giza pyramids were featured in one act; the Temple of Karnak in another. The archeologist also made detailed sketches of the costumes, finishing them in brilliant watercolor. In the hands of the master designers of Paris, there was every reason to expect that the Cairo designs would outshine even the glories of ancient Egypt itself.

hen, almost without warning, everything changed. On July 19, 1870, Emperor Napoleon iii declared war on Prussia. Most Parisians thought the French would crush the Germans in a week or two. But on September 1, the Prussians defeated the French at Sedan, captured the bulk of the French army, and took the emperor himself prisoner. By mid-September the Prussians had reached Versailles, and on September 20 they surrounded and blockaded the capital. The siege of Paris had begun.

hen, almost without warning, everything changed. On July 19, 1870, Emperor Napoleon iii declared war on Prussia. Most Parisians thought the French would crush the Germans in a week or two. But on September 1, the Prussians defeated the French at Sedan, captured the bulk of the French army, and took the emperor himself prisoner. By mid-September the Prussians had reached Versailles, and on September 20 they surrounded and blockaded the capital. The siege of Paris had begun.

For a brief time it appeared that, in addition to cutting off food and other supplies, the Prussians had also cut off all communications, but they had not counted on the resourcefulness of the Parisians. On September 23, the hot-air balloon Neptune floated out of Paris over the heads of the gaping Prussians and landed safely in Evreux, carrying 125 kilograms (275 lbs) of messages. Based on that success, the Minister of Posts in Paris established a regular balloon service, and for a time du Locle’s messages to Verdi arrived fairly reliably. As the bitter siege continued, however, the letters became fewer and further apart.

In contrast, letters from Ricordi, Verdi’s agent, were arriving at Sant’Agata at an ever-accelerating rate.

Shortly after Verdi had agreed to the Cairo contract, Ricordi had scheduled a performance of Aida in Milan. The proposed production date, February 1871, in no way infringed on the khedival contract, as the Milan production would follow the scheduled date of the Cairo premiere. But it was now November, and as Ricordi pointed out in every letter, La Scala’s management was becoming anxious. Would it be possible to prepare the posters? Ricordi asked. Could the management request subscriptions? What about hiring the musicians?

|

| BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE / ROGER-VIOLLET / BRIDGMAN ART LIBRARY |

| “As splendid as one can imagine,” instructed Mariette, whose set of the Temple of Karnak in Act ii of the premiere was adapted and reinterpreted in later years by other companies for performances such as this one above. |

As both Verdi and Ricordi knew well, the answers to those questions hinged on whether or not the sets and costumes could leave besieged Paris. If not, the Cairo premiere would certainly have to be postponed, and so would the Milan performance.

As November drew to a close, du Locle’s long-awaited balloon message finally arrived.

“Mariette is confined to Paris, as I am,” wrote du Locle. “All work on Aida has been suspended because there aren’t enough workmen. We do only one thing in Paris at this time: Stand guard.”

Barely had du Locle’s message arrived when Verdi received a letter from the manager of the Cairo Opera, Paul Draneht. He was not happy. Like Verdi, he had just learned that the costumes and sets would not arrive in Cairo in time for the scheduled premiere, and that Verdi apparently planned to present Aida at La Scala that February. Could it be that Verdi planned to premiere Aida in Milan, rather than Cairo?

Though Draneht did not wish to invoke the terms of the contract, he made his position clear. Should Aida be premiered anywhere other than Cairo, “…it would ever be a cause of genuine grief” to the khedive.

Verdi quickly assured Draneht that La Scala had already suspended preparations for the new opera, but added that the Milan opera house still intended to go ahead the following year. Fortunately for all concerned, the siege of Paris was lifted in January 1871. In short order, the costumes and sets were shipped to Cairo, and in September 1871 Verdi met Draneht in Geneva to place the completed score into the hands of the Cairo Opera impresario.

After months of work, and worry, it seemed that final preparations for Ismail’s beloved national opera were in their final stages.

|

| STAPLETON COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| This edition of the score was published in 1938. |

Only one problem remained. Following the indefinite postponement of the Cairo premiere, many of the original cast had accepted other assignments, leaving Draneht and Verdi to replace them on short notice. Fortunately, they agreed on most of the new principal performers, and Verdi was genuinely delighted when the gifted Antonietta Pozzoni agreed to sing the role of Aida. The role of Amneris was a different matter, however, and it was only after the young conductor Franco Faccio assured Verdi that the little-known Eleonora Grossi would do justice to the role that Verdi agreed to her selection, much to Draneht’s relief.

Mariette had his problems as well. “I consider it absolutely necessary that there be neither beards nor moustaches [on the performers],” he wrote to Draneht, explaining that the Egyptians had been clean-shaven as a matter of religion as well as custom. “Can you imagine the pharaoh with a turned-up moustache and a goatee?” he asked, worried that the performers’ vanity might detract from the authenticity of the production.

Draneht quickly assured Mariette that the performers would look Egyptian in every way, but even he became concerned when, the night before the opening, there appeared to be a problem with the machinery that moved the enormous Aida sets into place.

Yet on opening night, all was ready.

Verdi, not willing to overcome his dread of the sea, was not there, but the khedive was. And though he had sat through the entire opera at the dress rehearsal, he was as excited as anyone when the curtain rose to reveal an ancient Egypt more beautiful than even he had dreamed.

There was the handsome captain Radamès, equipped with a shield of solid silver. And there too was the vindictive Amneris, crowned with a tiara of real gold and precious stones. The Giza pyramids and the Temple of Karnak had shed their years to serve as the perfect background for the unfolding drama of two lovers doomed by the jealousy of a vindictive princess. And above all there was the music—Radamès musing of his love for the Ethiopian princess in the lyrical “Celeste Aida”; Aida’s soulful aria, “Numi, pietà del mio soffrir,” begging the gods to relieve her suffering; and finally the duet, “O terra, addio,” as the lovers die in one another’s arms.

The audience, which had bought up every ticket weeks before, sat mesmerized as Verdi’s soaring music carried them through the tragic story of Aida one scene after another until, late in the evening, the final curtain descended, eclipsing Aida and Radamès in their dying embrace as Amneris decried her fate in the temple above.

For a moment there was silence. Then, suddenly, the applause began. Almost as one the theatergoers rose to their feet and, with shouts of “bravo, bravo,” turned to face the khedive’s box. “Long live the khedive,” they cried again and again.

Slowly Ismail too stood up and nodded to the audience, but said nothing. There was no need. His bowed head and beaming face clearly reflected the immense relief he surely felt. The opera of ancient Egypt that Ismail had sought so hard to achieve was a phenomenal success.

|

|

| STAPLETON COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| “The sets will be based on historical accounts; the costumes will be designed after the bas-reliefs of Upper Egypt. No effort will be spared in this respect,” wrote Mariette, who produced detailed costume sketches for all of the main characters in the premiere. |

It was a success that would soon be repeated. On February 8, 1872, Aida opened at La Scala. Verdi was there to enjoy the seemingly endless applause and 32 curtain calls. On April 20, Verdi conducted Aida in Parma, then in Naples. By 1878, Aida had been performed in more than 130 opera houses around the world, from Buenos Aires to Vienna. It continues to be a standard in the repertory of most opera houses today.

As one critic observed, “Aida is the only grand opera from which it is impossible to cut a single note.”

Verdi saw it a different way. “Time,” he said, “will give Aida the place it deserves.”

And so it has.

|

Jane Waldron Grutz (waldrongrutz@gmail.com) is a former staff writer for Saudi Aramco who now divides her time between Houston and London, when she’s not on an archeological dig in the Middle East. Wherever she is, she always finds time to listen to Verdi’s wonderful music or, when possible, attend a performance of one of his most beloved works—the Egyptian opera, Aida. |