|

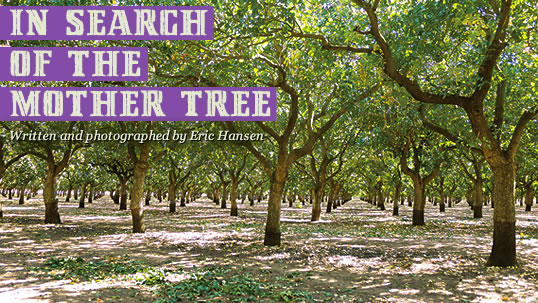

| The pistachio trees at Wolfskill Experimental Orchard allow botanists to continue research into Kerman and other new, promising pistachio varieties. |

In 1957, a small experimental orchard in Chico, California distributed to commercial nut-growers a promising new variety of pistachio tree from Iran, called Kerman.

The United States Department of Agriculture wanted to see how these Kerman trees might perform in the richly fertile Central Valley of California.

By 2013, the Kerman had created a billion-dollar agricultural industry, and what was once a delicacy was a long way toward becoming a common household snack. University of California pistachio specialist Louise Ferguson calls the California Kerman pistachio tree “the single most successful plant introduction of the 20th century.”

|

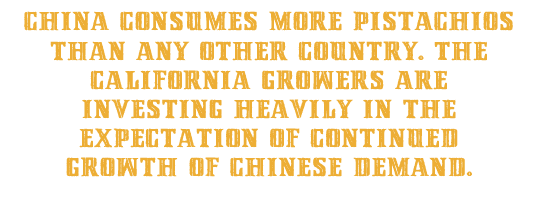

| Named for the Iranian city where the seed was gathered in 1929, the Kerman pistachio proved the best for California growers, thanks in part to its naturally large kernels—the nuts—that split their shells 60 to 75 percent of the time, making the pistachio an easy snack food. |

Humans have enjoyed pistachios for perhaps 9000 years. The Bible mentions them in Genesis (43:11). Archeological excavations at Jarmo, in northeastern Iraq, provide evidence that the nuts were collected from the wild and eaten as early as 6750 bce. Ever since, they have been an important food source and often a delicacy in the Middle East and Mediterranean, and as a result, the trees have been widely planted and cultivated for millennia. In Greece, pistachios were introduced in the fourth century bce following the campaigns of Alexander the Great. In the first century ce, during the rule of the emperor Tiberius, the nut was brought to Italy. The spread of Islam, along with the Crusades and the Venetian sea trade with Syria, helped further expand the cultivation and culinary popularity of pistachios in the Mediterranean basin and Europe.

The cultivated, nut-bearing pistachio tree, Pistachia vera, is a member of the Anacardiaceae, the cashew family, which also includes sumac, poison oak, poison ivy and mango. Pistachios need long, hot, dry summers and root-chilling cold winters, and they are dioecious, meaning there are male trees that produce the pollen and female trees that produce the nuts. The pistachio is originally from Central Asia, and it can still be found growing wild in parts of northeastern Iran, northwest Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Alan Davidson, author of The Oxford Companion to Food, noted that pistachio trees produce a good crop in alternate years. The nut is “the kernel of the stone of a small, dry fruit which looks like miniature mangos and grows in clusters.”

The pistachio, he continued, “with its unique color and mild but distinctive flavor, has always been a luxury, costing three or four times as much as other nuts. It is generally eaten roasted and salted as a dessert nut. In cooking it is often used as a garnish or decoration, both in sweet and in savory dishes. For example, it figures in some of the finest pilaf dishes, and in European Pâtés and Brawns which are served in slices, so that the nuts appear as attractive green specks or slivers.”

The most common example of this use in the West is in sliced mortadella, the popular Italian sausage. From the Middle East to North Africa, though, pistachio nuts are a common ingredient in sweets, lending their crunch and flavor to ice cream, French macarons, baklava, halva, lokum (Turkish delight) and biscotti.

In the us, although the first pistachio trees were officially introduced in 1805 by the New Crop Introduction Division of the newly founded government, more than 100 years passed before there was a concerted effort to develop them into a viable commercial crop.

|

| This metal tag identifies the tree that today grows at Wolfskill from a cutting taken from the Kerman “mother tree.” |

In 1909, to guide development of the vast agricultural potential of Califor-nia’s Central Valley, the usda opened a New Crop Introduction Research Station in Chico. Two decades later, in 1929, the usda dispatched plant specialist William E. Whitehouse to Persia (modern Iran) to collect pistachio seeds for the station. He returned with some nine kilograms (20 lb) of seeds, of different varieties. In 1930, Lloyd Joley, director of research in Chico, began field tests to determine the suitability of each tree to the Central Valley environment. Because it takes a pistachio tree seven to 10 years to produce fruit, it was not until 20 years later that Joley and his staff had results: Of 3000 trees they planted from Whitehouse’s seeds, one—which they had grown from a lone seed of its type—performed best. In 1952, they named this variety Kerman, after the city on the central plateau of modern Iran near which Whitehouse had collected the seed. They released it for commercial orchard trials in 1957, and today, all commercial pistachio trees in California come from this one “mother tree.”

I set out to find it.

A few months later, I was in Chico, standing—and nearly lost—in a chaotically overgrown, abandoned orchard section of the research station that had been closed since 1967. It was more like a habitat restoration area than a former experimental pistachio orchard. Pushing my way through 46 years of undergrowth, I was looking for metal id tags that identified the pistachio trees that remained. Of the few tags I could find, most were damaged or illegible. To further complicate matters, there were two sets of tags, each with separate number sequences, and I had only a partial list of the older set of tag numbers. The trees had been planted by row and number, but it was nearly impossible to determine where individual trees were located.

|

|

I was trying to get my bearings with an old, hand-drawn map that was photocopied for me by Robyn Scibilo, the site manager of the Chico Genetic Resource and Conservation Center, which took over the old research station orchards in 1992 and today works on propagating and improving some 130 species. With her map and helpful suggestions from several staff members, I wandered from tree to tree, looking for the most famous pistachio tree in the US. If it were still alive, it would be 83 years old. I was cautiously optimistic: Pistachios can live 100 or even 150 years. On the map, I could see two Kerman trees: one male and one female, side by side, at the top of Row 10. But the map was not drawn to scale, and there was no indication of north. I eventually identified a Hachiya persimmon on the map, lined it up with an ancient cork oak and then, keeping a flowering crab apple to my right, I headed southeast in search of the mother tree of all California pistachios.

Dan Parfitt is a pomologist, or fruit tree specialist, at the University of California at Davis’s Agricultural Extension Service. An expert on pistachio research and field trials, he had told me that no one could remember seeing the original Kerman tree since around 1983. This is the approximate date when cuttings were taken from most of the pistachio trees at Chico in preparation for cloning and re-establishment in the us Pistachio Collection at the National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Tree Fruit, Nut Crops and Grapes at Wolfskill Experimental Orchard, 160 kilometers (100 mi) south of Chico near the town of Winters, California. At that time, the original Kerman tree would have been some 50 years old. That would make it too large to move, and thus I was guessing that the original tree, if it were still alive, was still in Chico.

During an earlier visit to Wolfskill, John Preece, the supervisory research leader and horticulturist, showed me the entire us pistachio collection of approximately 750 trees. These include 10 distinct species and many hybrids from the Middle East, Greece, China, Italy, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan and Tunisia, as well as several other countries. Some of these pistachio species were not used for nuts at all, but rather for the turpentine or mastic that could be obtained from them, and others are suited to urban beautification—especially the landscaping tree Pistacia chinensis, with its spectacular, feathery red, yellow and orange fall foliage.

|

| Andy Schweikart of Pioneer Nursery holds one of some 890,000 rootstock pistachio saplings, all pre-ordered for growers eager to expand their orchards. Pistachios are now the second most valuable nut crop in the us, after almonds. |

I asked Preece about the Kerman in his collection. It was clear from its size that it had been propagated from a cutting, and that it was no older than 25 to 30 years. He agreed that if the original tree were still living, it would be in the old station orchard in Chico.

|

| Pistachio trees are pollinated by wind, not insects. The male flower of the Peters variety, left, turned out to best match the timing of the female Kerman's flower, right. |

Following its introduction in the 1950’s, the Kerman tree was a novelty for growers in the 1960’s and early 1970’s. In 1976, the crop yielded 680,000 kilograms (1.5 million lb). In 1979, growers got a surprise boost when us President Jimmy Carter imposed sanctions on Iran—then the world’s largest pistachio grower and exporter—in response to the taking of hostages in the us embassy. Among their many provisions, the sanctions banned pistachios.

Today, starting from the first female Kerman tree in Chico, there are more than 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) of pistachios growing in the Central Valley. At 270 to 360 trees per hectare, this translates into an estimated 31 million trees, which produce 98 percent of the total us pistachio crop. (The other two percent is grown in Arizona and New Mexico.) In 2010, with a harvest of 240 million kilograms (528 million lb), California surpassed Iran, which until then had remained the world’s top producer. This year, the value of the harvest for the first time exceeded $1 billion, surpassing the value of walnuts, and making pistachios the second most valuable nut crop in the US, after almonds. That means the average pistachio orchard is worth $75,000 per hectare ($30,000 per acre), and growers are so optimistic about the expanding market that they are planting 4800 to 6000 additional hectares (12,000 to 15,000 acres) of pistachios every year.

Today, starting from the first female Kerman tree in Chico, there are more than 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) of pistachios growing in the Central Valley. At 270 to 360 trees per hectare, this translates into an estimated 31 million trees, which produce 98 percent of the total us pistachio crop. (The other two percent is grown in Arizona and New Mexico.) In 2010, with a harvest of 240 million kilograms (528 million lb), California surpassed Iran, which until then had remained the world’s top producer. This year, the value of the harvest for the first time exceeded $1 billion, surpassing the value of walnuts, and making pistachios the second most valuable nut crop in the US, after almonds. That means the average pistachio orchard is worth $75,000 per hectare ($30,000 per acre), and growers are so optimistic about the expanding market that they are planting 4800 to 6000 additional hectares (12,000 to 15,000 acres) of pistachios every year.

Richard Matoian, executive director of American Pistachio Growers, estimates that by 2017 the harvest will exceed 360 million kilograms (800 million lb), and there is, he is confident, plenty of global market. According to the California Pistachio Commission, 65 percent of the crop is exported, mainly to China and Europe. China consumes the most pistachios of any single country—some 77 million kilos (170 million lb) a year—and the California growers are investing heavily in the expectation of continued rapid growth of this demand.

Yet the Kerman is not the perfect nut for everyone. While it produces a large, firm nut with good flavor, many connoisseurs regard the Sicilian pistachio Napoletana to be the world’s most highly flavored and physically attractive pistachio nut. Other experts in other countries, unsurprisingly, disagree, claiming the pistachio crown for Turkey’s Uzun or Kırmızı varieties, Syria’s Red Aleppo or Iran’s Momtaz or Kalehghouchi.

|

| A member of the cashew family and related to sumac, poison ivy and mango, pistachios grow in bunches. |

But taste, any grower will say, is but one criterion for success. Kerman is a “heavy producer”—lots of nuts per tree—and Kerman nuts have a high percentage of natural splits to their shells that make them easy to open and eat. The Kerman also grows well in the deep boric, calcareous soils of the Central Valley, whose climate resembles those of the Mediterranean and Central Asia.

And even so, the Kerman did not thrive unchallenged. In the late 1960’s, early growers found that it was susceptible to a common, slow-spreading root disease called Verticullium wilt. At about the same time, two friends interested in going into pistachios—dentist Ken Puryear and row farmer Corky Anderson—traveled to Chico from the southern San Joaquin Valley to meet Joley, who had selected the original Kerman. Joley advised Puryear and Anderson, and they planted their first trees in 1969. As their legend goes, a large pistachio grower came to look at their young trees, offered to buy the lot, and he came back with an order for a similar number of trees for the following year. Instead of planting an orchard, the pair formed Pioneer Nursery to develop rootstock for the new pistachio industry.

In response to Verticullium wilt, Pioneer Nursery experimented and found that Pistacia atlantica crossed with various hybrids of Pistachia integerrima created a disease-resistant hybrid, which they called Pioneer Gold 1. Then, bud-grafting Kerman onto those crosses, by 1981 they gave pistachio growers the solution.

|

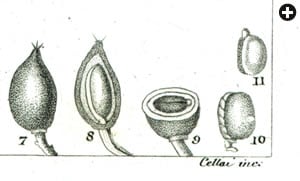

| FLORILEGIUS / ALAMY (DETAIL) |

| This 1837 botanical illustration shows a whole fruit, then slices through it vertically and horizontally; the stone (or shell); and the edible kernel. |

There was one last bit of horticultural fine-tuning left, and this had to do with finding a suitable pollinizer whose viable period overlapped the extremely brief, one-week receptive bloom period of female Kermans. Pistachios are pollinated by wind, not insects, and in a commercial orchard there is typically one male tree to every 8 to 24 females. The male pistachio Peters (parentage unknown but possibly Armenian) was already growing near Fresno, and it produces large quantities of pollen for approximately two weeks—two weeks that match the female Kerman bloom perfectly. With the rootstock and pollinizer problems solved, by the early 1980’s the new industry had a superior tree that it could depend on for quality, disease resistance and large yields.

When I visited Pioneer Nursery, manager Andy Schweikart gave me a tour of the vast acreage completely filled with saplings about 125 centimeters (4') tall. Overhead sprinklers bathed the trees in a gentle mist.

How many? He estimated 890,000. And every one of them, he added, “pre-ordered, paid for and ready for delivery. We will have even more ready for sale, same time next year.”

My next destination was Dewey Farms in Yolo County, 50 kilometers (30 mi) north of Sacramento, where I went to watch the harvest. Pistachio trees bloom in April, and they are harvested from early September through mid-October. The development of the nut within the shell often forces the hard shell to split, a phenomenon we rely on to make it easy to eat the nuts. (In Iran, the term to describe this natural split shell and the resulting partly exposed kernel is khandan—“laughing.”) The percentage of natural splits for Kerman are typically 60 to 75 percent. The remaining unsplit nuts must be sorted out and then mechanically cracked.

|

| During the harvest season in late fall, operators at Dewey Farms use mechanical shakers to work Central Valley pistachio orchards 24 hours a day, filling half-ton boxes that are trucked to processing plants. |

Pistachios harvesting is done with powerful, mechanized tree shakers. These grab the tree trunk and shake it for several seconds. The resulting shower of nuts is caught in long, fabric-covered frames. According to Harry Dewey, who oversaw the operation at his farm, the harvest is sometimes done in stages: a light shake for early-maturing nuts followed by a more vigorous shake for later-maturing nuts. The long catch-frames that surround the tree are sloped, and they direct the rolling nuts onto a conveyor belt, which sends them into wooden harvest bins, each of which holds approximately half a ton of nuts. The bins are loaded onto trucks, and the trucks take them to the processing plant, 24 hours a day during the harvest season.

|

| The nuts are dried and sorted, and some are roasted and salted. |

Just outside the San Joaquin Valley town of Wasco, I visited one such plant, the Primex Pistachio Processing Plant. Getting permission to enter and photograph inside a state-of-the-art plant like Primex is not easy—proprietary processing features need to be kept confidential. But once inside the immaculate, high-tech, 3250-square-meter (35,000-sq-ft) plant, general manager Mark Sherrell showed me around.

Harvested pistachios, he explained, must be delivered from the orchard, hulled and dried within 24 hours to avoid shell staining that renders them visually unattractive. Upon arrival at Primex, the fleshy outer skin is removed and the nut is dried from its original moisture content of about 30 percent down to 10 percent, which Sherrell says is what ensures an unblemished shell. Further drying, down to five to seven percent moisture, takes several more days, and at that point the pistachios are “stabilized,” that is, they can be stored until they are ready for shipping. The pistachio is unique in that its split shell allows roasting and salting without first removing the shell, and that is how about 80 percent of pistachios are eaten, says Sherrell. The rest are shelled mechanically and sold either fresh—often for candies, baked goods and ice cream—or roasted and salted.

|

| Pistachios have long been a favorite nut in sweets from the Middle East and Mediterranean. From top left, clockwise: Pistachios in jelled confection wrapped in toasted sesame seeds; whole pistachios over jelled sugar; chopped pistachios in nougat; chopped pistachios in sugar gel. |

All of what I had seen so far made me wonder about the wisdom of betting a billion-dollar industry on the health and continuing well-being of a single female cultivar, the Kerman. As any farmer knows, “monocultures” are risky businesses, as they can be invitations to pests and diseases on epidemic scale. For precisely this reason, the California Pistachio Commission and the University of California teamed up in 1990 to search for new pistachio varieties. One of the most promising varieties is turning out to be Kalehghouchi, also from Iran.

Back in Chico in the abandoned orchard, the sun was beginning to set when I finally came upon a Kerman tree. It was alive, but its flowers showed that it was a male, and the id tag confirmed it. I was standing at Row 10, but here, the orchard abruptly stopped. In front of me was just an open, dusty field, cleared—recently it seemed—and plowed. I had a Google Maps satellite view printout showing a second Kerman tree, just to the east, which I now realized was almost certainly the female. Then I looked down. The sawdust from the chainsaw was still almost fresh around a stump.

On my hands and knees, in the fading light, I counted the growth rings. There were 82 of them: 2013 minus 82 equals 1931—the approximate year Lloyd Joley planted out the first Kerman. I later learned that the “mother Kerman” died last year and was cut down only three weeks before my visit. The dead branches and trunk were thrown onto a nearby burn pile. The mother tree had been reduced to ashes, but its progeny live on.

|

| In western desserts, pistachios appear perhaps most often in ice cream, in a simple cone, or (right) in a fancy ice cream sandwich—as produced here by Ginger Elizabeth Chocolates of Sacramento—between French macarons made from almond meal, sugar and egg whites. |

|

Best-selling author and photojournalist Eric Hansen (ekhansen1@gmail.com) is a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World. He lives in California’s Central Valley, surrounded by the world’s greatest concentration of pistachio orchards. |