The future impresario was born in the pine-forested, hilly enclave of Sultantepe, on the Asian side of Istanbul, on July 31, 1923, a week after the Treaty of Lausanne granted international recognition to the Turkish Republic led by Kemal Atatürk. Ertegun’s father, Mehmet Münir, was part of the Lausanne negotiating team, and he stayed on in Europe for 10 years to serve as Atatürk’s ambassador to Switzerland, France and Britain. In 1936, when surnames became mandatory in Turkey, Münir chose “Ertegün” (air-teh-gən), “living in a hopeful future,” as his family name

Ahmet Ertegun’s first childhood memory was playing in the gardens of the Turkish embassy in Bern, Switzerland. Later, in Paris, he attended an exclusive lycée, where he achieved perfect scores in French and calculus. In London, Ertegun and his younger sister, Selma, were put under the care of a strict English governess whose previous charges had been Princess Elizabeth, the future queen, and her younger sister, Princess Margaret.

Ertegun’s mother, Hayrünisa, was an accomplished musician who could play any keyboard or stringed instrument by ear. She bought the popular music of the day, and at night, Ertegun and his elder brother, Nesuhi, would sneak her records into their rooms. In 1932, Nesuhi took Ahmet to the London Palladium to see Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington. “I had never really seen black people,” Ertegun recalled in a 2005 interview. “And I had never heard anything as glorious as those beautiful musicians wearing white tails, playing these incredibly gleaming horns.” His infatuation with jazz got a boost two years later when his father was posted to Washington, D.C. as the Republic of Turkey’s first ambassador to the United States.

In Washington, Ertegun found himself in the rarified atmosphere of an all-boys private school, but as he noted later, he got his “real” education at the Howard Theatre. Located in the heart of what was then simply “the black district,” the Howard was where Ertegun got to meet Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong and Lionel Hampton; according to The New York Times, it was Ertegun who was the first person ever to ask Ella Fitzgerald for her autograph.

|

| joe gottlieb / library of congress |

| In the 1940’s, Ertegun often invited black and white musicians to mingle and jam together at the embassy. Here a group gathers around a bust of Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Turkish Republic. In 1947, Ertegun founded Atlantic Records. |

Unhampered by the heated politics of race, Ertegun and his brother arranged Washington’s first integrated concert at the only venue that would allow black and white musicians to play on the same stage before a mixed audience: the Jewish Community Center. Then, the two took the extraordinary step of inviting musicians they had seen performing at the Howard on Saturday nights to come to Sunday lunches at the Turkish embassy. It was not a hard sell to their parents, especially their musician mother, or to the musicians themselves, who—after being served by white-jacketed waiters—gathered in the embassy ballroom to jam. In photographs of the time, jazz luminaries wearing impeccably tailored double-breasted suits are standing in front of a huge bust of Kemal Atatürk. One of these integrated gatherings prompted an outraged letter to the ambassador from a southern senator, who wrote: “A person of color has been seen entering your house by the front door. In my country this is not a practice to be encouraged.” The ambassador responded: “In my country, friends enter through the front door, but if you wish to come to the embassy, you can enter from the back.”

In 1940, at 17, Ahmet entered St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, where he studied the arts and literature, mathematics and philosophy, and a new language each year. He graduated with honors in June 1944. Four months later, as the embassy was astir preparing for a reception celebrating Turkey’s 21st year of independence, Münir Ertegun, the 61-year-old ambassador, felt a sharp pain in his chest. He died two weeks later.

“I am deeply grieved by the news of the sudden death of my personal friend, the Turkish Ambassador,” us President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in a press release. The ambassador’s body was kept at Arlington National Cemetery until the end of World War ii, after which it was returned to the family home in Sultantepe aboard the uss Missouri.

Faced with choosing between careers in diplomacy or music, Ertegun followed his heart. “What I really loved was music—jazz, blues—and hanging out. And so, I did what I loved.” He moved into an apartment near the embassy, and he hung out at the Quality Music Shop, a record store in the ghetto owned by Max Silverman, later known as “Waxie Maxie,” where old jazz 78’s could be bought for as little as a dime apiece or three for a quarter. It was only steps away from the Howard Theatre.

One of his mother’s musical gifts to him, at age 14, had been a toy record-cutting machine. Now, in 1947 at age 24, Ertegun decided to set up a real record-cutting company. During the war, shellac—a key ingredient in the manufacture of records—had been rationed. As a result, such major record labels as rca Victor, Columbia and Decca had dropped what was then called “race music” to concentrate on white audiences. Though the postwar economy was putting spending money into the pockets of people of all colors, even in sophisticated New York, Harlem residents couldn’t go downtown to the Broadway theaters. As Ertegun once put it, “Black people had to find entertainment in their homes—the record was it.”

Lionel Hampton, who knew Ertegun from the Howard, offered to invest $15,000 to help launch Ertegun’s company. They both went to see Gladys, Hampton’s money manager, who also happened to be his wife. Ertegun waited outside. Within minutes he heard Gladys screaming: “You’re what? You’re going to give our money to that little jerk who’s never worked a day in his life?” Years later, when Hampton visited the plush offices of Atlantic Records, he could be heard to mutter: “To think all this could have been mine!”

Ertegun turned to an old family friend, a dentist named Vahdi Sabit. Ertegun’s pitch went over so well that Sabit mortgaged his home to plop down $10,000. Atlantic Records was born, its name inspired by a west-coast record label called Pacific Jazz. Unlike many other executives in the growing record industry, Ertegun understood and actually liked the music he made. His hours at Waxie Maxie’s had taught him much about the music business, and he had developed a refined sense of the records people would like and buy, as well as of new trends.

|

| arnaud de rosnay / condé nast archive / corbis |

| Pop duo Sonny and Cher produced three hit albums for Atlantic between 1965 and 1967, when this photo was made in Los Angeles. |

As Ertegun explained in a 2007 article in Rolling Stone: “A black man lives in the outskirts of Opelousas, Louisiana. He works hard for his money; he has to be tight with a dollar. One morning he hears a song on the radio. It’s bluesy, authentic and irresistible. He must have this record. He drops everything, jumps in his pickup and drives 25 miles to the first record store he finds. If we can make that record, we’ve got it made.”

Ertegun set up shop in a tiny suite in a derelict hotel in midtown Manhattan, but he recognized that the talent that would make or break Atlantic Records was to be found in crowded, smoke-filled haunts in the Deep South. So off he went.

One night in New Orleans, Ertegun set out in search of an obscure genius who went by the name “Professor Longhair,” who he heard was playing in a joint across the Mississippi River. No white taxi driver would take him into the black area, so his cabbie dropped him off in the middle of a field to walk a mile in the dark, his only light coming from a house in the distance that, as he got closer, literally vibrated from the sounds of a piano, drum and loud singing. When Ertegun walked in, what he thought sounded like a band turned out to be none other than Professor Longhair, playing solo on a piano with an attached drumhead that he hit with his right foot. As people danced, Ertegun was mesmerized by this completely original artist who was making a kind of music he had never heard before. Rushing up to Longhair—whose real name was Henry Roeland “Roy” Byrd—during his break, Ertegun asked him to sign with Atlantic. “I’m terribly sorry,” Longhair said. “I signed with Mercury last week.” Then he added: “But I signed under my own name.... With you, I can be Professor Longhair.”

|

| michael ochs archives / corbis |

| From the mid-1960’s on, Ertegun embraced what in the us was called “The British Invasion.” In April 1967, he advised Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and producer Felix Pappalardi of the band Cream while recording “Strange Brew,” the song that became the lead single on its landmark album, “Disraeli Gears.” |

Following in Longhair’s footsteps, Ruth Brown, Big Joe Turner and Clyde McPhatter also signed with Atlantic in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s. But it was Ray Charles who came to define Atlantic on the national scene. Up to that point, Charles played in the smooth style of Nat King Cole—he had never played boogie-woogie piano. When Ertegun explained the sound he wanted, Charles suddenly began, in Ertegun’s words, “to play the most incredible example of that style of piano playing I’ve ever heard. It was like witnessing Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious in action—as if this great artist had somehow plugged in and become a channel for a whole culture that just came pouring through him.”

In 1952, Ertegun brought Jerry Wexler into Atlantic. The intense, brilliant former Manhattan street kid turned Billboard writer had coined the term “rhythm and blues” in 1947, a style that soon after became just “R&B.” During their collaboration, Ertegun and Wexler began to realize that their biggest target audience was no longer rural and black, but teenaged and white. This became clear in 1954 when Big Joe Turner’s version of “Shake, Rattle and Roll” was recorded by white musicians Bill Haley & His Comets and Elvis Presley. Ertegun and Wexler realized that the blues had to change to meet the tastes of bobbysoxers who were hungry for a sound beyond R&B—the new rock and roll.

In 1955, Nesuhi Ertegun, who had married and moved to Los Angeles, announced he was going to work for Imperial Records, the label on which Fats Domino recorded. Ahmet couldn’t bear the thought of his older brother working for a competitor and persuaded him to come to New York to head Atlantic’s jazz division. Within a year, Nesuhi Ertegun had signed and recorded the Modern Jazz Quartet and jazz bassist Charles Mingus. In 1958, Ertegun took Bobby Darin into the studio and cut “Splish Splash” and “Queen of the Hop,” both hits aimed at the kids who watched “American Bandstand” on the latest entertainment medium—television.

One night in 1960, Ertegun’s life took another turn: Friends introduced him to a Romanian émigrée who had fled her country after the Communist takeover. Her name was Mica, and they married the following year.

|

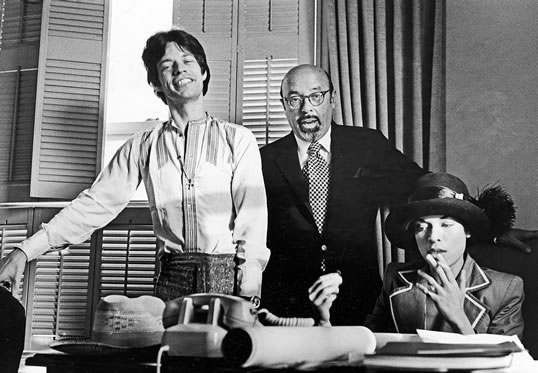

| julian wasser / time & life pictures / getty images |

| “A painful, ecstatic courtship” was how Ertegun described his pursuit of the deal with The Rolling Stones that helped make Atlantic the top us label in the early 1970’s. In this undated photo, Ertegun is flanked by Mick and Bianca Jagger. |

Riding Atlantic’s success wave, Ahmet and Mica lived in high style in a Manhattan townhouse crammed with paintings by Hockney, Warhol and Magritte. On a road trip through Turkey in 1971, they fell in love with an Aegean retreat in Bodrum. Mica restored it, supposedly using ancient stones from the ruins of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Vanity Fair called a summer invitation to spend time with Ahmet and Mica in Bodrum “the hottest ticket in town.”

There were other tickets, too, as their parties mixed music stars, diplomats, financiers, movie stars, avant-garde artists and literati. At one party the Erteguns threw for the Rolling Stones on the roof of New York’s St. Regis Hotel in 1972, the guest list included Tennessee Williams, Bob Dylan, Huntington Hartford, Oscar and Françoise de la Renta and a host of titled nobles; entertainment was by Count Basie and Muddy Waters. Jacqueline Onassis, Truman Capote, Diana Vreeland and the Duke of Marlborough were all frequent visitors at their home.

Rolling Stone magazine described him this way: “Ertegun looked like a suave, wealthy and titled combination of Oriental pasha and the Wizard of Oz; he spoke with a smoky, gravelly drawl in a patois of hipster-cool, … maybe five different accents all flowing together, as he assayed all around him through tortoise-shell glasses, eyes often at half-lid. He was always turned out with a precisely trimmed goatee and never a wrinkle in his clothes…. He was one of those people who knew exactly what the right thing to do was at all times.”

Into the 60’s and 70’s, the hits kept flowing. Sonny and Cher’s “I Got You Babe” became an international blockbuster. In 1970, Ertegun rushed to Los Angeles to pursue a distribution deal with The Rolling Stones, beginning what he later called “a painful, ecstatic courtship.” Ertegun and Mick Jagger played cat and mouse, and while Jagger entertained numerous offers, Ertegun eventually won him over—but only after finally making Jagger dial Atlantic’s office repeatedly for some 45 minutes while Ertegun sat coolly by the ringing phone, just to make Jagger sweat. Landing the Stones locked Atlantic’s position as the top record label in America.

Into the 60’s and 70’s, the hits kept flowing. Sonny and Cher’s “I Got You Babe” became an international blockbuster. In 1970, Ertegun rushed to Los Angeles to pursue a distribution deal with The Rolling Stones, beginning what he later called “a painful, ecstatic courtship.” Ertegun and Mick Jagger played cat and mouse, and while Jagger entertained numerous offers, Ertegun eventually won him over—but only after finally making Jagger dial Atlantic’s office repeatedly for some 45 minutes while Ertegun sat coolly by the ringing phone, just to make Jagger sweat. Landing the Stones locked Atlantic’s position as the top record label in America.

In the 1980’s, Ertegun’s philanthropic side began to emerge when he became the driving force behind what became the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, opened in 1995. He picked the museum’s architect (I. M. Pei) and its venue (Cleveland). Hard choices had to be made to reconcile the formality of a museum with the raucous spontaneity of rock and roll, and here, Ertegun the diplomat helped arbitrate good taste.

On October 29, 2006, the 83-year-old Ertegun attended a benefit concert by The Rolling Stones for the Clinton Foundation at Manhattan’s historic Beacon Theatre. After former President Bill Clinton spoke, Ertegun waited in a backstage lounge. At some point he tripped and fell, striking his head on the concrete floor. He was rushed to the hospital, but lapsed into a coma. Six weeks later, he died.

|

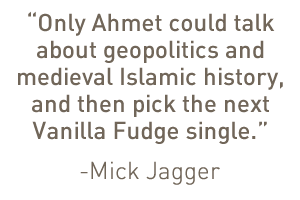

| JEFF CHRISTIANSEN / REUTERS / CORBIS; EAMONN MCCORMACK / GETTY IMAGES |

| At the 2004 annual induction ceremony for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which Ertegun helped found, he stood with Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone, and Mick Jagger. |

Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft, lent his Boeing 757 to bear Ertegun’s body and his family and friends to Istanbul to bury him at the family gravesite in Sultantepe, where his mother, father and older brother (who had died in 1989) were also buried. Ertegun’s body was lowered into the ground wrapped in a traditional white kefen, or burial shroud.

The following year, Henry Kissinger expressed his regard for Ertegun at a tribute concert in New York. “Ertegun was vastly entertaining, but he was, above all, sensitive, thoughtful, incredibly generous and caring. He loved music, and he loved his artists. He was extraordinarily loyal to his friends. He cared deeply for Turkey, acting as an unofficial permanent ambassador of Turkey in Washington and as a spokesman for America in Turkey.”

In London that same year, Atlantic’s Led Zeppelin, which Ertegun signed in 1968 and helped to sell more than 300 million records, reunited for a rock-filled tribute to the music mogul in the O2 Arena. More than 20 million fans from across the globe vied for the lottery distribution of 20,000 tickets at £125 ($250) each.

“Everybody wanted to do something to show how much we loved the guy,” recalled Led Zeppelin lead singer Robert Plant in a 2012 interview. Profits from the show benefited the Ahmet Ertegun Education Fund.

|

| JEFF CHRISTIANSEN / REUTERS / CORBIS; EAMONN MCCORMACK / GETTY IMAGES |

| Mica Ertegun, center, stands outside the newly opened Ertegun House at Oxford University with Ahmet Ertegun Education Fund scholars last year. |

“Although he was deeply into music, my husband was very keen on education,” said Mica Ertegun at a ceremony at Oxford University in February 2012. “With so much strife in the world, it is tremendously important to support things … that help human beings understand one another and make the world a more humane place.”

In its January 25, 2007 issue, Rolling Stone had called Ertegun “the greatest record man who ever lived, who signed some of the greatest rhythm & blues, jazz and rock artists of all time, guided their careers, their education, their records, and built Atlantic Records, the historic label that was home to these artistic treasures.”

Ertegun always knew a good song when he heard one, and he put it on vinyl faster than any record could spin. Through the eras of 45’s, eight-tracks, cassette tapes, cds and into today’s digital musical world, Ertegun laid down beats that still go on today.

|

Gerald Zarr (zarrcj@comcast.net) is a writer, lecturer and development consultant. A former Foreign Service officer, he is the author of Culture Smart! Tunisia: A Quick Guide to Customs and Etiquette (2009, Kuperard). |