|

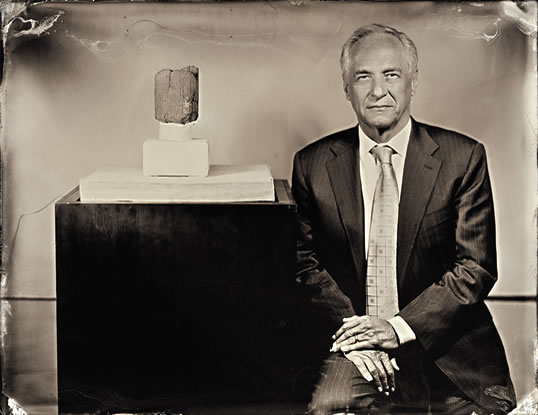

| Leo Schmitz is deputy chief of Englewood 7th District for the Chicago Police Department. He started as a patrolman and was promoted to patrol and detective division sergeant, then to lieutenant in patrol and Area 4 Gangs. |

“Basically my job—and it’s probably the same for the Medjay chief of police back then, though we can’t ask him—is that we are both in charge of individuals who report to us and we’re charged with protecting the people. Protect people who are weak. Take care of the children and the elderly. Our job is to make things safe to ensure people can have a good life. I am sure that they were doing the same back then that we are doing now. In general terms, police are police no matter where they are in the world. He was doing the same thing I’m doing. It’s good to hear that the police profession has been going on that long. There’s a lot of things that we can do with technology that help us clear cases, but it really comes down to getting the bad guy. It probably took longer back then to find the bad guy or it might have taken a shorter time, but we all strive for the same thing: We’re going to find out who did it, and we’re going to go after them. In the end, it’s still the same theory, same idea.”

POLICE From at least 1600 bce, the Egyptians had a professional police/desert patrol/security force called the Medjay. Initially, they were made up of Nubians, a people famed for their archery skills and as trackers in the desert. The weapons they carried consisted of a bow and arrows, battle axes, slings and spears. They carried rectangular shields. The Medjay were divided into ranks. The entry-level Medjay appear to have been patrolmen. Men with supervisory titles had greater responsibilities, including reporting crimes, sitting on the local court, testifying against those accused of crimes and attending interrogations, as well as more ordinary administrative duties. Police were state employees. The chiefs reported to the vizier (akin to a prime minister), or to the highest official of the temple.

Shown with: Brown granite statue of a chief of police, from the Ramesside period, Dynasty xx, ca. 1127 bce, Medinet Habu, Luxor, Egypt. (28.7 cm / 11¼") This statue depicts a man seated on a cushion with his robe pulled over his knees. The inscription on the front and back of his garment identifies him as the “chief of the Medjay of Western Thebes, Bakenwerel.” This Bakenwerel is probably the same Medjay chief who was part of the team that investigated the robbery of tombs in Western Thebes in about 1110 bce.

|

| Margie Smigel has been a broker for residential and investment real estate for nearly three decades. She is owner of the Margie Smigel Group, llc real-estate brokerage in Chicago. She is also a graphic designer, photographer, filmmaker, poet and writer. |

“I know that [the stone] has something to do with a real-estate contract, and when I saw it, I thought, ‘This must be what they mean by “it hasn’t been written in stone,”’ because this is written in stone! Today, everybody gets a survey at closing, so they actually have a pictorial representation of what they’re buying. It all probably comes from this. They just keep changing the required documentation over the years. But the survey is something that hasn’t essentially changed. Everything is still on paper at closing…. But this is so much more elegant than all those papers—this is so beautiful. It would be nice if at least your deed were in stone. Wouldn’t it be lovely to carry home the tablet of your deed from your closing? The irony is that I just started a new real-estate business, and my goal is to make it completely paperless…. What artifacts will remain of our present-day transactions thousands of years from now?”

LAND AND PROPERTY Most documents from Mesopotamia in the Early Dynastic period (ca. 2700–2350 bce) concerning land and property relate to the temple and palace, including agricultural estates and houses in the city owned by these institutions. The “Chicago Stone,” described below, is probably a rare example of a declaration of property acquired by an unnamed elite individual in this period.

Shown with: The basalt “Chicago Stone” from the Early Dynastic period, ca. 2600 bce, Iraq. (25 x 32 x 5.5 cm / 9¾ x 12½ x 2") Written in the Sumerian language, this rectangular stone slab is called the “Chicago Stone” because of its current home. It is one of the oldest known display documents relating to real-estate transfers in Mesopotamia. The nine columns of text written on each of its two sides record the sale of a number of fields, probably to a single buyer, who is unnamed. Land-sale records of the period usually record acquisition of property by single buyers from several sellers, collections of individual and separate transactions. In the Chicago Stone, the buyer makes a grand account of many distinct purchases. Purchases were paid in silver as well as oil, wool, bread and sheep fat. The signs on the stone represent early cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”) writing that still resembles pictographic signs (picture-writing). Typical of early texts, the signs are organized into “cases” (ruled boxes) that include personal names and quantities of items. This text was read vertically from top to bottom, beginning with the leftmost column on its front (flat side).

|

| Diane Mayers Jones is a Chicago fashion designer who specializes in custom formal wear for women. She was initially self-taught, but later formally trained. She also gives introductory and advanced sewing courses in her studio, Dzines by Diane. She has been in business for more than 20 years. |

“As I look at her, she’s wearing this dress and I’m blown away, because I am a dress person. I am always wearing a skirt and blouse or a dress, so as I look at her, I think, ‘Wow,’ you know, ‘She’s got on this beautiful wrapped dress.’ ….I love making beautiful dresses, beautiful prom and wedding dresses; some of the garments that I make are just so—you know—with the times, a lot of wrapping, a lot of draping. When I see her, she’s got a little draping going around the front with the low-cut collar, it’s just wonderful. I feel like we are so bonded here. If I did a little tweaking, it could be worn by the women of today. The work that actually goes into a garment of this style took so much longer in the past because they had to do everything by hand. These people worked hard at what they did. You can see her hands are cupped together in reverence to God. I’m a very religious person, and it makes me think of myself.”

TEXTILES AND COSTUME Textiles made in ancient Mesopotamia were traded widely and were much in demand. Old Akkadian cuneiform texts (ca. 2220 bce) from Tell Asmar (ancient Eshnunna) mention institutions where women and orphaned children produced high-quality textiles, mainly using sheep’s wool. Flax, used to make linen, may also have played an important role in the textile industry. Plain-weave linen has been found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur (ca. 2500 bce). It could take many weeks to produce a high-quality piece of cloth on a loom, depending on the material, the weave count and elaborations. The material of the cloth represented on the female statue shown here is unknown; it was most likely sheep wool rather than linen, which was apparently reserved for priests, high officials, rulers or statues of deities.

Shown with: Limestone female statue from the Early Dynastic iii period, 2650–2550 bce, Sin Temple ix, Khafajah, Iraq. (36.1 cm / 14¼") This standing female figure is depicted wearing a shawl, likely one piece of cloth roughly the size of a single bed sheet. It was probably wrapped around the body and draped over the left arm, leaving the right arm and shoulder and lower legs and feet exposed. The figure represented here is likely to have been a woman of relatively high status.

|

| Ron Vasser has been involved with horses on the competitive level for over 20 years. He has been associated with riding groups and is certified in mounted search-and-rescue operations. |

“Looking at a piece like this reinforces my understanding that I am doing something that people did thousands of years ago. The bit I use may be a little flashier, or the metal may be different, but the concept is the same, so I am living part of that history at this moment. First thing you want to know when you’re on a horse is, can I make him stop? You want to know where the brakes are, you want to know where the steering is. After that, you’re golden. Having that bit is a way of controlling the horse. Any person who is into horses can look at that and say, ‘Oh, that’s a bit’—a bizarre-looking bit because of how it’s designed, but basically they could see that’s probably a snaffle bit.... It appears to have some ridges,... something that would give the horse rider a little bit more control in the horse’s mouth.”

HORSES Horses appear in ancient Mesopotamian textual sources by around 2100 bce, and the earliest images of people riding horses appear in the Near East around 1800 bce. Horse-drawn chariots were introduced to Egypt via the Levant soon after, during the Hyksos era, and were highly prized status symbols. By the first millennium bce, horses were more commonly used for cavalry by the Assyrians, and subsequently by the Medes and Persians. Classical sources mention that the Achaemenid Persians (550–330 bce) developed body armor for both their horses and their riders.

Shown with: Bronze horse bit from the Achaemenid period, ca. 550–330 bce, Persepolis, Iran. (22.4 x 2.3 cm / 8¾ x 1") This horse bit is one of several found in the so-called Treasury and Garrison Quarters at the royal city of Persepolis. It has bar-shaped cheek pieces and a flexible snaffle (jointed) bit made in two sections linked in the center. Double loops on the bars were used to attach the headstall straps. The larger rings at the ends of the bit would have been attached to the reins.

|

| Robert Zimmer joined the University of Chicago in 1977 and became the University’s 13th president in 2006. He is known for establishing the University of Chicago’s “Zimmer Program,” which involves understanding of symmetry and the relationship of geometry and topology to certain algebraic structures. |

“If you look at this tool, which is a kind of multiplication table, in spite of various views to the contrary, I do believe that the kind of basis of understanding that you get from actual drill and mastery [of times tables] is an important thing…. One of the beauties of the structure of mathematics is that it becomes multi-layered, so that at any moment you create a degree of mastery that gives you a capacity to now think about the next thing. So if you never establish foundations, if you never establish mastery at a foundational level, it inhibits your capacity to think about the next things. When one thinks about what mathematics is actually about at a fundamental level, it really does go back to thinking about counting,… about measurement, to thinking about shape, and understanding those in increasingly sophisticated ways…. The way that they connect other sorts of phenomena … that you see today in mathematics you see reflected in this object right here. Living without zero is difficult, but obviously, people were able to do a great deal without it, which is really kind of impressive.”

MATHEMATICS The Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000–1600 bce) was a time of intense scribal activity; we know the most about scribal education. Much of what we know today about Mesopotamian mathematics comes from the cuneiform tools and textbooks that instructors used to teach their students, and the provision of practical mathematical and metrological skills necessary for scribal bureaucracy. Mesopotamian mathematics used the sexagesimal system of notation, with calculations based on the number 60 rather than the base-10 system that we use today. The concept or notation of zero was not established until much later by mathematicians of the early Islamic world.

Shown with: Mathematical tables inscribed on a clay cylinder from the Old Babylonian period, ca. 2000–1600 bce, Iraq. (13.9 h. x 11.2 cm. dia. / 5½ x 4½") This object is one of the earliest known collections of mathematical tables written on a cylinder. It was suspended with a cord or held upright on a post that passed through the hole at the center. The scribe could spin the cylinder to the column he wanted to read. The text begins with a table of reciprocals and continues with 37 separate multiplication tables.

|

| Haki Madhubuti is an author, educator and poet. He is one of the founding members of the Black Arts Movement, and the founder and publisher of Third World Press (established 1967). Now retired, he writes full-time. |

“Any people who are in control of their own cultural imperatives are about the healthy replication of themselves and their communities. This replication starts with language and writing. Gilgamesh obviously was an activist, in terms of trying to find a worldview that he could understand and explain and bring back to his people. What I understand from Gilgamesh, on one level, is that we make our lives essential not only to our civilization but to the furthering of civilization. And writing is about that. Storytelling is about that. All too often cultures are not recognized unless they create something, unless they leave a legacy.… The oral tradition is passed down from generation to generation, but in the written tradition, we see more permanency. With the oral tradition, interpretations keep changing. You give one story to a child, and it goes through the grandfather, but by the time it gets to the next generation, it’s changed several times. When you have the written tradition, you have something that’s going to stay; you have something to build upon, and obviously you can interpret it also.”

THE EPIC OF GILGAMESH Gilgamesh was probably a historical figure, a king of the city of Uruk (in southern Mesopotamia, in what is now Iraq) in about 2800 bce. The legends that grew up about him in both Sumerian and Akkadian (languages of ancient Mesopotamia) probably began as oral traditions, later collated by scribes to form what we today call the Epic of Gilgamesh, the most elaborate and popular of Mesopotamian literary compositions. In the poem, Gilgamesh, who is described as part god, part man, tyrannizes his subjects in the city of Uruk. The gods create the wild man Enkidu to distract him. Gilgamesh and Enkidu fight, then become great friends and join forces to defeat the monster Humbaba in the Cedar Forest. Upon their return to Uruk, they are met by the goddess Ishtar (Inanna in the Sumerian version), whose advances Gilgamesh spurns. Punished by the gods for attacking Ishtar, Enkidu dies, leaving Gilgamesh to consider his own mortality and to seek immortality, which he cannot attain. Gilgamesh realizes that although he will not live forever, his monuments and exploits will continue after his death. The most complete copy of the Akkadian version was written on 12 tablets and formed part of the library of King Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–627 bce) at Nineveh, Iraq. The Epic of Gilgamesh is recognized today as a literary classic and the oldest known epic poem.

Shown with: Clay tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh, from the Old Babylonian period, ca. 1800–1600 bce, Ishchali, Iraq. (11.8 x 6.2 x 3.0 cm / 4½ x 2½ x 1¼ ") This corresponds to the contents of the third tablet (of 12) in the later version of the Epic of Gilgamesh found in the library of Ashurbanipal, and contains part of an early version of the story of Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s journey to the Cedar Forest. And with: Clay plaque depicting Gilgamesh, from the Isin-Larsa period to the Old Babylonian period, ca. 2000–1600 bce, Iraq. (28.2 x 8.5 x 5.2 cm / 11 x 3¼ x 2") This depicts what may be Gilgamesh standing on the head of the slain Humbaba, monster of the Cedar Forest. Gilgamesh was a semi-divine character who is said to have reigned for 126 years and was 11 cubits tall (equivalent to more than five meters, or 16').

|

| Gloria Margarita Tovar is a nail technician at the Elizabeth Arden Red Door Salon in Chicago. |

MANICURIST

“They [the Egyptians] probably had to look presentable for other people, to make them see who they were. They knew there were kings, so they had to look nice—the same as today. Even when you have a job, and you go to an interview, you have to look nice. Color makes them feel good. Like when I’m done, and I put on a color, they’re like, ‘Oh my god, my hands look gorgeous, the color just makes me feel like a new person,’ and that’s what I see, and that’s what I enjoy—seeing the expressions on their face. Well, first of all, when I heard about [how long there have been manicurists], I thought it was amazing. It’s amazing because I have always said that back to the earliest times, we always took care of ourselves. You know, our hair, our skin, so when I saw this piece, I said, ‘It’s still here, it’s just a different way.’”

MANICURISTS Both men and women in ancient Egypt were very concerned with their appearance, and they lavished special attention on grooming. Scenes in private tombs dating to the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties (ca. 2450–2181 bce) show men giving manicures and pedicures. The scenes are accompanied by short texts giving the men’s titles, indicating that they were organized into ranks, from simple manicurists to managers and supervisors of manicurists.

Shown with: Limestone relief of a manicurist from the Old Kingdom, Dynasty v, ca. 2430 bce, tomb 19, Saqqara, Egypt. (75 x 32 x 4 cm / 29½ x 12½ x 1½") This is a section of a door lintel from the tomb of a man named Kha-bau-Ptah, who gives his title as “overseer of the palace manicurists.” He is shown seated on a chair, holding a staff that was the mark of an elite man. Kha-bau-Ptah’s tomb, with its stone portico and expensive decoration, indicates that he was a wealthy man.

|

| Kofi Nii has been a taxi driver in Chicago since 1989. His cab is equipped with a good sound system that features the music of reggae greats such as Bob Marley. A native of Ghana, he worked as a merchant seaman before settling in Chicago. |

“Those wheels date back to … an age that I wasn’t even born, and they look very interesting. I know that in those days people had to have more stuffing for their ears because [the wheel is] metal, it will make some noise, a lot of noise…. It would wear out quick [on Chicago’s streets]. In those days, they were using the wheel to transport merchandise, you know, wheat, and something to go and sell; so it’s transportation, and right now that’s what I’m doing, transporting people, from point A to point B. Without the wheel there won’t be transporting, because you can’t find a square block and put it on the car; it’s got to be a round wheel…. Yeah, I say amen to those who invented it. I guess that’s how they derived the ‘horsepower’ for the cars, from the horse pulling,… you know,… mechanical horsepower … how many [horsepower] your car get?

WHEELED TRANSPORTATION Transportation in the Near East was important for trade, communication and warfare. The earliest wheeled wagons were in use from around 3500 bce in the Caucasus and Eastern Europe, and the earliest wheeled transportation in Mesopotamia is known from depictions of four-wheeled wagons dated to around 3300 bce. They were usually made of hardwoods like elm and tamarisk, with rawhide as a tire and metal fittings or bandings for the axle and securing pin. Wheel size was important for maneuverability and speed; the larger the wheel, the faster the vehicle.

Shown with: Iron wheels with bronze hubs from the Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Sargon, ca. 705 bce, Iraq. (23.1 x 0.8 cm / 9 x ½") These miniature wheels were found at the Neo-Assyrian capital at Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin (“Fortress of Sargon”). They probably came from a ceremonial cart or wheeled stand that did not survive its burial. During the Iron Age (ca. 1200–586 bce), as iron working became more widespread, metals such as bronze or iron were used as bands or hoops around wooden wheels to add strength and durability without compromising speed.

|

Jason Reblando (jason@jasonreblando.com) received a ba in sociology from Boston College and an mfa in photography from Columbia College, Chicago. His photographs are part of the collections of several museums, and he teaches photography at Illinois State University. |

|

Matthew Cunningam (matthewbcunningham@gmail.com) is a multimedia producer with more than 15 years’ experience producing stories for Chicago Public Media’s daily news and weekly arts programming. He is currently the creative producer and principal at Truthful Enthusiasm in Chicago. |

|

Jack Green (jdmgreen@uchicago.edu) is chief curator of the Oriental Institute Museum and a research associate of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. He is co-editor of the Oriental Institute Museum publication Picturing the Past: Imaging and Imagining the Ancient Middle East. |

|

Emily Teeter (eteeter@uchicago.edu) received her doctorate from the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. She is an Egyptologist, research associate and coordinator of special exhibits at the Oriental Institute and the editor of exhibit catalogs. |