|

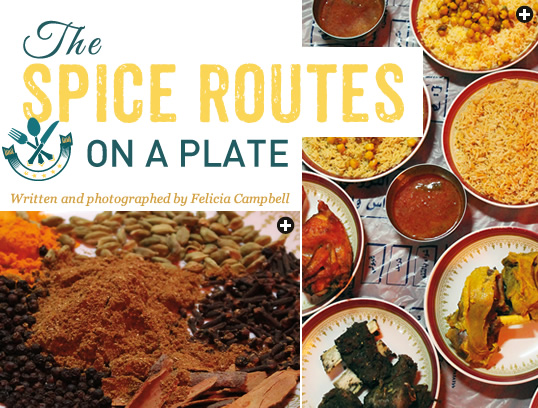

| Left: Top Omani spice staples include (clockwise from lower left) black peppercorns, turmeric, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon and a mix of ground cumin and coriander. Right, from top left, clockwise: a silky, tomato-based hot sauce called daqus; subtly Omanized biryani; broth-cooked mandi rice; daqus; boiled goat; the richly spiced shuwa (which can take a day or more to cook); red pepper-rubbed, pan-roasted chicken; and qabooli rice, which uses at least eight flavorings. All are served on plates-to-share at a banquet hall specializing in traditional foods. |

A FEW MONTHS AGO, I KNEW CLOSE TO NOTHING ABOUT THE COUNTRY EAST OF YEMEN AND SAUDI ARABIA, SOUTH OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES AND ACROSS THE GULF FROM IRAN. I’D TRAVELED AND STUDIED FOOD CULTURE THROUGHOUT THE MIDDLE EAST, AND I KNEW MUCH ABOUT ITS NEIGHBORS, BUT I COULDN’T IMAGINE WHAT OMAN LOOKED LIKE, SOUNDED LIKE OR—ESPECIALLY—WHAT IT TASTED LIKE. I BEGAN DIGGING, DISCOVERING OMAN’S HISTORY AS AN INTERNATIONAL TRADING EMPIRE AND, SOON AFTER, ITS CUISINE, RICH WITH MILLENNIA OF FUSIONS, SULTRY SPICES AND FLAVORS, UNLIKE ANYTHING ELSE I HAD ENCOUNTERED IN MY TRAVELS.

he story of modern Oman is not much older than I am, beginning as it did in 1971 with the ascent to power of Sultan Qaboos bin Sa‘id, but the story of Oman as an empire, with Muscat as its hub, is thousands of years old. Since the sixth century bce, Muscat’s strategic position, at the intersection of maritime routes to India and Asia and overland caravan routes to the Eastern Mediterranean, made Muscat not merely powerful but also coveted. The Portuguese, on their way to India, mounted a bloody invasion in 1507 and achieved complete conquest in 1514. The Ottoman navy and the Persians fought alongside the Omanis in an uprising in 1546, but the Portuguese maintained their supremacy until 1650, when they were expelled by Sultan bin Saif al-Arubi. The Ya‘arubid Dynasty also expanded the Omani empire to East Africa by taking over the Portuguese garrison of Fort Jesus in Mombasa in 1698 and expelling the Portuguese from the rest of the coast in what is today Mozambique and Zanzibar. A civil war in 1718 weakened the empire, and Oman came under Persian rule for less than a decade, but by 1749, Ahmad ibn Sa‘id, the governor of Suhar, drove them out too, and was elected Imam. Sa‘id went on to establish the hereditary sultanate that continues today.

he story of modern Oman is not much older than I am, beginning as it did in 1971 with the ascent to power of Sultan Qaboos bin Sa‘id, but the story of Oman as an empire, with Muscat as its hub, is thousands of years old. Since the sixth century bce, Muscat’s strategic position, at the intersection of maritime routes to India and Asia and overland caravan routes to the Eastern Mediterranean, made Muscat not merely powerful but also coveted. The Portuguese, on their way to India, mounted a bloody invasion in 1507 and achieved complete conquest in 1514. The Ottoman navy and the Persians fought alongside the Omanis in an uprising in 1546, but the Portuguese maintained their supremacy until 1650, when they were expelled by Sultan bin Saif al-Arubi. The Ya‘arubid Dynasty also expanded the Omani empire to East Africa by taking over the Portuguese garrison of Fort Jesus in Mombasa in 1698 and expelling the Portuguese from the rest of the coast in what is today Mozambique and Zanzibar. A civil war in 1718 weakened the empire, and Oman came under Persian rule for less than a decade, but by 1749, Ahmad ibn Sa‘id, the governor of Suhar, drove them out too, and was elected Imam. Sa‘id went on to establish the hereditary sultanate that continues today.

|

| None taller than six stories, Muscat’s white, neotraditional buildings give its downtown a feeling that visitors and residents alike find pleasant for strolling, shopping—and eating. |

The 18th-century sultans continued to expand the empire by establishing trading ports in Persia and along the Makran coast, in what is now Pakistan. By the early 19th century, Oman had become the most powerful state in Arabia. Trade flourished from the Far East to the British Isles.

But in 1856, when Sultan Sa‘id bin Sultan Al-Busaid died, conflict broke out over his succession. His two sons divided the state, one ruling the East African holdings from Zanzibar and the other ruling Muscat and Arabian Oman. In the early 20th century, the former empire was further weakened by rebellions in the interior; separatist revolts followed in the 1960’s, fueled by a poor economy and the unpopular social and economic restrictions of Sultan Sa‘id bin Taymur.

In July 1970, Sa‘id bin Taymur’s son, Qaboos bin Sa‘id, overthrew his father in a bloodless palace coup. The new sultan established a modern monarchy, and appointed a cabinet and an elected consultative council. He began an aggressive modernization campaign, building public schools, roads, hospitals and clinics and opening opportunities for economic growth. The last 40 years have been prosperous, and yet the need to preserve Omani culture and art has been recognized.

As a result, the skyline of modern Muscat could not be more distinct from those of the capitals of other Gulf states. Muscat’s buildings uniformly gleam white or reflect a tawny sand color, with no steel-and-glass, and none more than six stories high.

The sense of history and esthetics carries over into fashion, as all male government employees dress in the dishdashah, the Omani style of the long white robe worn throughout the Gulf region. Many—but not all—wear a single tassel hanging off the right side of their collars and round, colorfully embroidered hats atop their heads. Women walk and shop in a mix of black abayas and blue jeans. The national ethnic mix is apparent immediately, too: At any given table, a dark black Omani might be sitting with two countrymen who appear South Asian or Persian. The calm streets, quietly buzzing with conversation and laughter, are enough to make anyone feel relaxed—and hungry. Though restaurants offering international cuisine, from pizza to sushi, abound, I was here to gain a deeper understanding of the city and the country through its own food.

|

| Dining on traditional fare that has been adapted to Oman from Baluchi origins, the Lashko family enjoys goat meat pan-fried with tomatoes and onions in an Omani spice mix heavy with black pepper, served with date chapati (flatbread) and a salad of local vegetables. |

Three years ago, Sultan Qaboos began sponsorship of an Oman food festival, which became part of the annual Muscat Festival that celebrates and shares Omani heritage. There students from the Oman Tourism College cook traditional foods for up to 50,000 festival visitors. At the college, I met Zuwaina Al Fazari, an instructor in culinary studies who also hosts a televised Ramadan cooking show about traditional holiday dishes; its name translates to “Dishes and Taste.” It is important, she explained, because today “fewer and fewer children want to learn from their mothers. It is only later, when they have left home or gone abroad, that they realize how special those flavors and foods are. We must preserve these traditions, write them down and teach them, so that we will never lose that aspect of ourselves.”

Al Fazari told me that in Muscat, there are four major ethnic groups that influence Omani cuisine. There are the Baluchi, whose ancestors were Persians from the city of Gwadar, now in western Pakistan; Liwatiyyah traders, who came from coastal towns in northern India and southern Pakistan; Zanzibaris, who came from East Africa; jabalis, or “people of the mountains”; and tribes from the interior, who are “the ones who have always been here.” In this way, she said, “All the foods we eat are traditional Omani. They just draw on different pasts.”

|

|

| At the Lashko home, Omani chicken coconut curry, top, is smooth and mild, and it lacks the lemongrass and hot peppers that are familiar in the recipe's better-known counterparts from Thailand. Above: Served with a scoop of white rice, traditional paplou is a bright, flavorful soup made with fish stock, lemon juice, cilantro, fennel, turmeric and garlic together with soft, sautéed chunks of onion and fresh-caught tuna. |

Most Omani food is cooked and eaten at home, but for large events such as weddings, families often turn to caterers. In Barka, about an hour outside Muscat, I visited a catering and event hall that specializes in traditional Omani cuisine. In the outdoor kitchen, metal vats the size of Jacuzzis were set on gas burners, and men were making stacks of the crispy, paper-thin Omani bread called khubz rakhal, made with only flour, water and salt. In pits, burning embers cooked whole goats and lambs through a slow smoking process for the heavily spiced celebration dish shuwa.

At the dining tent, I stopped at the entrance to remove my shoes, and then stepped onto a red-carpet floor where Asian screens sectioned off family-size dining areas. A waiter spread a plastic tablecloth on the floor, and I sat at the edge and watched as dish after dish appeared, each one offering subtle clues to its origin.

Two small bowls appeared first: Daqus, a silky red hot sauce made from tomatoes, garlic and ground red chiles and thinned with vinegar, has its origins in the Dhofar Governorate in the southernmost part of Oman, where cooks long ago integrated the New World tomatoes and chiles that arrived in the holds of ships from South Asia. The daqus was placed next to a yellow bowl of lentil soup with vermicelli noodles and chopped carrots, the noodles a Muscati addition to the Arab staple—also courtesy of trade with the Far East. Next came a sampling of the Omani rice triumvirate, at least one of which almost always appears on the dinner table. Biryani is a sweet dish of white rice topped with chickpeas and caramelized onion, layered with spices, nuts and dried fruit, and laced with saffron soaked in rosewater for a subtle “Omanization” of the ubiquitous South Asian specialty. Qabooli is a complex, subtly flavored rice made by frying tomato, onion and chile paste, then boiling the paste with rice, chicken, shredded cardamom, cinnamon, ground turmeric and black pepper. Topped with chickpeas, it is a perfect dish alongside spicier meat dishes but hearty enough to eat on its own—an important factor in its place of origin in the Omani interior. Mandi, the plainest-looking but most savory of the rice dishs, is white rice boiled in meat broth with pepper and cinnamon. It is served alongside crisp-skinned chicken quarters whose pan-fried, salty skin tastes of cardamom, cloves, black pepper and cinnamon. Pieces of boiled goat, whose broth very well may have helped flavor the mandi, sit in a bowl next to the most famous Omani dish of all: shuwa.

|

A task usually reserved for ‘Id celebrations, making shuwa requires rubbing a whole lamb or goat with a wet mixture of oil and ground spices, often a combination of red pepper, black pepper, cloves, cardamom, cinnamon, cumin, dried lime and turmeric, then wrapping it in palm or banana leaves and placing it in a pit over hot embers. It cooks very slowly for 24 to 48 hours, until the smoke and spice and fat have penetrated the meat, the rub has charred to a crisp crust, and the flesh pulls easily off the bone. This is a dish whose cooking method originates with the Bedouin tribes in the interior of Oman and whose spices tell of the many peoples they have interacted with over the centuries, from the Zanzibari cloves, to the South Asian cardamom, peppers and cinnamon and the New World capsicums, and on to the Persian cumin and coriander and the local Omani specialty, black lime. (See sidebar at saudiaramcoworld.com.) In the most traditional of dining rooms, eating the most traditional of foods, I felt I was tasting the entire network of spice routes on my plate.

The next morning, at the fish market in Mutrah, fishermen hawked baby shark, which is used in specialties of the eastern coastal region, like awal, a fresh-shark soup, or dried for use in stews. There was hamour (grouper) and king fish, possibly destined to be salted or ground into fish kebab, and tuna, most likely to be thrown on the grill or salted and set aside to make al-malih, a dried saltfish, with some fresh pieces finding their way into paplou soup or biryani. There were sardines, which might also be grilled, or might be crushed into madqouka kashie (pounded dried sardines) with red chiles and cardamom, or might be pressed with oil to make the Gulf-wide delicacy mehyawa, which is served spread on flatbread for a crispy, funky snack. Finally, I found koffer fish, specific to the Arabian Sea and a delicious meal on its own, grilled or pan fried or tossed in any of the many Omani versions of fish curry.

|

| Exploring “nouveau Omani” cuisine, Ubhar restaurant founder Ghada Al Yousef plies her diners in Muscat with creative appetizers that include, from left, a roast meat (shwarma) “money bag,” samosa filled with cheese and mint; a “Zanzibari potato puff” and a mini-kebab—alongside popular crowd-pleasers of hummus and babaganoush. |

Later that evening, I followed an invitation to taste one seafood delicacy at the suburban home of Sarah Lashko, whose mother has faithfully preserved the family’s Baluchi recipes. North out of Muscat, passing miles of tranquil beaches and palm trees, I arrived at her gracious home, surrounded by a sprawling lawn, just as the sun was setting. She led me inside to a long dining table already set with a spread of dishes made from her mother’s traditional recipes. As I had hoped, the meal began with paplou, a bright, flavorful soup made with fish stock, lemon juice, cilantro, fennel, turmeric and garlic and soft, sautéed chunks of onion and fresh-caught tuna. Eaten with a scoop of white rice, it was both refreshing and comforting.

While we savored the soup, Sarah’s father talked about the fish market in Mutrah I had visited, explaining that although the fish caught on the Omani coast are some of the best in the world, foreign export demand had driven up the prices, thus reducing the domestic fish market to a shadow of its once bustling self. Nonetheless, fish remains one of the staples of the Muscati diet.

We then moved on to the main dishes, using savory, date-flavored chapatis (flatbreads) to scoop up goat meat that had been pan-fried with tomatoes and onions in a black pepper-heavy Omani spice mix. The unsweetened date flavor of the bread—an interesting local twist on the South Asian specialty—beautifully complemented the slight heat of the meat. On another serving plate there was chicken coconut curry that was neither like a Thai dish (no lemongrass, no hot green pepper) nor like an Indian curry: Instead, it was mild, with a subtle, silky richness. The finale of the meal was a carrot dessert, not unlike a bread pudding, but made by boiling shredded carrot in milk for hours to extract a delicately sweet taste and custardy texture—similar to Indian gajar halwa. It was served with mint tea and light Omani coffee, which looks and tastes a lot like tea because it’s made with barely roasted coffee beans.

|

|

| PAPLOU, KABULI SAMAK, HALWA AL JEZAR: DAWN MOBLEY |

| Top: Shown here with her siblings, Sarah Lashko has preserved her mother’s recipes. Above: Shark meat in an onion and tomato curry. |

The meal acknowledged the Lashko family’s South Asian roots while being firmly planted in, and informed by, the Omani ecology, history and palate. Underlying the ethnic inflections and origins of the dishes, all I tasted was Oman: the unusual twists on the ubiquitous chapati and chicken curry only made the Omani distinctions clearer. I began to feel that I was discovering the magic of Omani cuisine. I wondered, however, about contemporary Oman: Was the spirit of adventure and discovery still here, or were young Omanis content to look to their parents and grandparents for a purely historical culinary identity? I hoped to find out the next day at Ubhar, Muscat’s first and most prominent “modern Omani” restaurant.

Dressed casually in a velvet tracksuit, her long brown hair moving with her as she leaned back in a rose-pink upholstered chair, Ghada Mohammed Al Yousef explained the origin of her sleek, downtown eatery’s name. In the southern desert, at the edge of the Peninsula’s Empty Quarter, an entire, intact city was discovered under the sand and limestone in 1993. “There had been stories of Ubar in legend,” she said, “of people from frankincense traders to the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon all passing through the city, but until it was uncovered, it remained only legend. Now, it is part of history.” In the same way, she wants to offer a taste of a “real, but long-hidden Oman,” modern, true representations that also draw on the past.

When Ubhar opened in 2009, Ghada expected primarily tourists but, to her surprise, it was locals who crowded her dining room. “I realized my generation is like me. We have global tastes from traveling abroad; we are educated professionals,” she explained. “We love our country and our heritage, but also crave new tastes and experiences.

|

|

| PAPLOU, KABULI SAMAK, HALWA AL JEZAR: DAWN MOBLEY |

| Ubhar often approaches local specialties playfully. For example, top, camel biryani is demurely served on fine white china instead of the traditional large communal platters. At Kargeen Caffe in Muscat, shuwa is presented more elaborately (above): leaf-wrapped and set on a bed of rice in a traditional brass bowl. |

“We Omanis have mixed with the world for centuries, from intermarriage to food; why would that change now?” In today’s ever more globalized world, the influences on Omani cuisine simply come from farther away. Examples at Ubhar are Ghada’s Chinese-inspired fish dumplings floating in her variation on paplou soup, or the French puff pastry encasing shwarma meat in her “money bag” hors d’oeuvres, or Omani walnut-and-date halwa, also wrapped in puff pastry and served with chewy frankincense ice cream. She even takes house-made shuwa and presses it between slices of flatbread like Italian panini. Other global trends present in more subtle ways, like her commitment to promoting Omani home businesses by purchasing pickles from housewives and using fresh, local ingredients whenever possible, such as the Omani eggplant she mashes to make a light baba ghanoush without sesame tahini. She also isn’t afraid to play with local dishes as inside jokes, for example, serving camel biryani—tender and more subtly flavored than either goat or lamb—elegantly on white china, in delicate portions rather than on the traditional large communal tray. Every dish, she said, is a refined version of a classic, with the foreign twists somehow rendering them no less authentic. It is, she added, the oldest Omani technique: artfully absorbing foreign influences and naturalizing them.

Later, I met Miad Al Bulushi, an international-relations specialist and former us State Department legislative fellow, at a seaside café. We enjoyed fresh-pressed juice and talked about the culture and food of this city at the intersection of the spice routes. Miad’s flowing headscarf and her exposed wisps of red hair fluttered beautifully in the breeze. “We don’t rush toward change,” she said, “but always try to engage in balanced exchange with newcomers, learning all we can from them, without trying to become anything we are not. We cherish our identities, and no outside force can change that.” The result is food that, whether served at home, on the floor of a banquet tent or in an urban-chic restaurant, is just as confident, adventurous and curious as the Omani people themselves.

|

Felicia Campbell (k.felicia.campbell@gmail.com) is an associate editor at Saveur magazine. She holds a master’s degree in Middle Eastern food culture from New York University, and she is currently working on her first book, a memoir about her transformative experiences as a young us soldier in the Iraq war. |