|

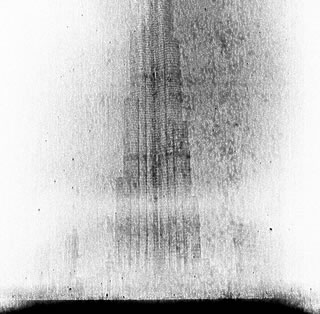

| Rula Halawani, “Traces” series, 2013. Photographic prints, courtesy of Selma Feriani Gallery. |

Amid more than a decade of rapid growth of Middle Eastern contemporary art, photographic art has led the way.

To many, the phrase “photography from the Middle East” has generally meant little more than news images from conflict zones. This limiting perception has changed markedly over the last decade, as photographic art from the Middle East and North Africa has become one of the brightest new stars in the contemporary art constellation.

Although its roots go back much farther—arguably to the very beginning of photography itself—the entry of Middle East contemporary photo-art onto the world stage can be dated to 2004, when the prestigious annual Noorderlicht photography festival in the Netherlands devoted itself to the Arab world with an exhibition called “Nazar” (“Look”). While at the time it may have appeared as a one-off, boutique-theme show, it planted the seeds for a flowering of interest in photographic art both inside and outside the Middle East that matured alongside other media in contemporary art.

Although its roots go back much farther—arguably to the very beginning of photography itself—the entry of Middle East contemporary photo-art onto the world stage can be dated to 2004, when the prestigious annual Noorderlicht photography festival in the Netherlands devoted itself to the Arab world with an exhibition called “Nazar” (“Look”). While at the time it may have appeared as a one-off, boutique-theme show, it planted the seeds for a flowering of interest in photographic art both inside and outside the Middle East that matured alongside other media in contemporary art.

In 2012, London’s Victoria & Albert Museum mounted “Light from the Middle East,” a survey of more than 30 photographers from the region. The following year, Liverpool’s Look Festival put on “I Exist in Some Way,” a significant exhibition of Middle East photography, while in the us, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts exhibited “She Who Tells a Story,” the first major show of women photographers from the Middle East. Most recently, in March, the biennial FotoFest in Houston showcased photographic art by 49 artists from the Arab world, one of the largest exhibitions of Arab art of any kind. It was especially notable for showing 12 artists from Saudi Arabia, now one of the fastest-growing photo-art scenes in the region.

In addition to these high-profile shows, group and solo exhibitions of Middle Eastern photo-artists have become almost commonplace in public and private galleries around the world. But why is contemporary photographic art from this part of the world commanding such attention? To find out, I sought insights from six of the region’s most prominent photographic artists as well as art-world experts.

|

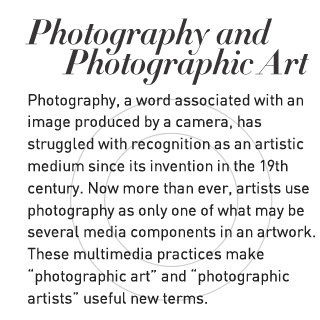

| Lalla Essaydi, “Harem #2,” 2010. Chromogenic print, courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery. |

LALLA ESSAYDI was one of the stand-out exhibitors at the 2004 “Nazar” show, and today she is one of the most successful artists working in any medium from the Arab world. Her photographs are held in dozens of major public and private collections. In common with many photo-artists from the Middle East and North Africa, Essaydi has an in-depth, lived experience of the broader world beyond the region.

“My work has involved a long and ever-deepening exploration into what constitutes my own identity as an artist, a woman, a Moroccan and someone living in the 21st century, where a certain degree of cultural nomadism—I now live in the West—has become in a sense the norm,” she says.

Essaydi also has extensive knowledge of global art history, and as well as being about her own cultural identity, her images respond—at time subtly and at other times pointedly—to centuries of western Orientalists who frequently eroticized their depictions of Middle Eastern women.

“My work reaches beyond Islamic culture to invoke the western fascination with the veil and, of course, the harem, as expressed in Orientalist painting,” she says, adding that many of her photographs are the products of elaborate scene-staging that can take months to construct.

|

| Youssef Nabil, “Catherine Deneuve, Paris,” 2010. Hand-colored gelatin silver print, courtesy of The Third Line Gallery and Nathalie Obadia Gallery. |

The rise of Middle Eastern photo-art, she offers, is a product of “global nomadism and global modernization, technology and social media,” and “perhaps it is because of the recent unrest in the Middle East that its art is becoming more popular, driven by artists’ desire to show a global audience their interpretation of what is really happening there, as well as a reflection of audiences who are increasingly keen to understand the region from a new angle.”

YOUSSEF NABIL, born in Egypt but, like Essaydi, living in the us, was also one of the “Nazar” show’s leading lights who has since earned world renown. He has mounted on four continents numerous solo exhibitions of his traditional black-and-white photography that he colors by hand using antique methods. At the beginning of his career in the early 1990s, while still living in Egypt, Nabil was heavily influenced by his homeland’s cinematic tradition, which is the most prolific in the Arab world. By contrast, his more recent subjects have tended to come from farther afield, though they often retain a connection to cinema, such as his recent portraits of French actresses wearing a hijab (headscarf).

Nabil points to the Gulf countries as major drivers of the new global visibility of contemporary Middle Eastern art, including photographic art. “Suddenly, with Dubai’s economic boom around 10 years ago, they just helped create this channel, putting Middle Eastern artists on the map, attracting viewers at art fairs, at auctions. It was through Dubai first, then afterwards Abu Dhabi and Qatar with the museums and collections. They are giving artists from the rest of the region a window to show their work.”

Aside from this boost, Nabil also feels that the region’s time, artistically speaking, had simply come. “It was about time that the world knew about art from the Middle East, the same way they knew about Chinese art, Indian art, Latin American art,” he says. “It just made sense. It seemed to be time to acknowledge the artists of this region.”

|

| Mitra Tabrizian, “Leicestershire” series, 2012. C-type photographic print, courtesy of the artist. |

Given their global popularity, it is perhaps no surprise that both Nabil and Essaydi featured in the Victoria & Albert’s 2012 show, which also included non-Arab photographic artists from the region, such as the widely exhibited MITRA TABRIZIAN, currently a professor of photography at the University of Westminster.

“Having been born in Iran and educated in England, going back and forth has given me the advantage of observing both cultures from an outsider’s point of view,” she explains. “Belonging neither here nor there provides a sense of detachment, as well as engagement, and thus perhaps a different understanding.”

Made in both England and Iran, Tabrizian’s work contains a good deal of social commentary, and she cites intellectual as well as artistic influences, from the noted British writer, artist and photography-theorist Victor Burgin, under whom she studied, to the French philosopher and critical theorist Jean Baudrillard and the German polymath Berthold Brecht. If viewers cannot always tell where her images were made—“East” or “West”—that is fine with her, even to her point. Of her series titled “Another Country,” which focuses on a Muslim community in London, she says, “It was received very well, and the audience was confused whether this is East or West.”

|

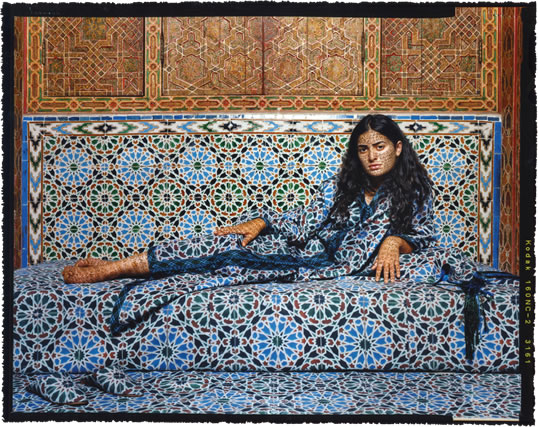

| Samer Mohdad, “Mes Arabies” series, Morocco, 1994. Photographic print, courtesy of the artist. |

|

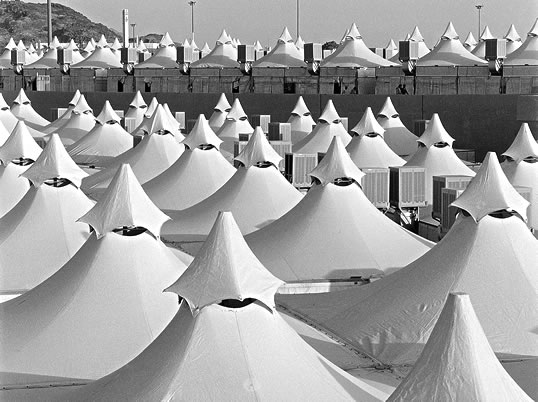

| Reem Al Faisal, “Hajj” series, 1999-2003. Gelatin silver print, 76 x 100 cm, courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery. |

Tabrizian believes that the rising profile of Middle Eastern photographic arts has complex causes, including the confusion, or “the inability to understand the political situation,” that results in “interest in the artists from that region and how they may interpret or view life.” She also has a more pragmatic hypothesis: “Since in the current atmosphere the market seems to be dictating contemporary art, the East is a new area of exploration and exploitation,” she says.

Her point on economics is readily echoed by Francis Hodgson, the photography critic for the Financial Times in London and a former head of the photographs department at Sotheby’s, one of the world’s leading auction houses. “Every sector has seen a lot more of the Middle East in recent years, from horse racing to banking to travel to a variety of other art activities,” he says. “The obvious reason is the money. In spite of its caricatured reputation as stuck-in-the-mud with colonialist values and pre-revolutionary class structures, the rich West is remarkably adaptable and flexible—you’d be astonished at how well tweed-clad persons from [western institutions] adapt to the Middle East when they’re after the money. Part of the payback is ‘taking an interest’ in local expressions of culture. The same is true of China, India, even Russia. Where there’s emerging money, there’s a lot more interest.”

|

| Rula Halawani, “Intimacy V” series, 2004. Photographic print, courtesy of Selma Feriani Gallery. |

Consequently, he says, some Middle Eastern photo-artists are all too mindful of this. “It may be that the center of gravity of the art world is moving, as it periodically does. But I take that with a certain caution. The fact is that while a great deal of very interesting and high-quality photographic activity is now being generated in the Middle East or North Africa, it is still being generated for consumption mainly in New York and London and Paris. A great proportion of the ‘value’ of Middle Eastern contemporary art is only in fact validated by success in those older capitals,” he says. “We have to see that there is such a thing as export art, art made to be appreciated in countries other than the countries of its origination.”

Even so, he is keen to charge the term “Middle Eastern photographic art” with oversimplification. “I don’t think one can easily lump together, for example, the boom in Iranian art photography, the new museum of photography in Marrakech, citizen-journalism in Cairo or the rise of protest-art photography in Palestine,” he says.

It is this very complexity that helped draw FotoFest co-founder Wendy Watriss to the region’s photo-art. “I find the work intensely intelligent,” she says. “I don’t think of it as mono-structural as ‘photography.’ Most of the artists in the [FotoFest] exhibition cross back and forth between many media—moving and still, two-dimensional and multi-dimensional. Like the work, these are artists of the world. Their work is multi-layered and informed by many different aspects of political, cultural and geographic history. It is sophisticated work.”

|

| Abdulnasser Gharem, “Siraat” (“The Path”), 2010. Custom-made led lightbox, 73 x 123 cm, courtesy of Ayyam Gallery. |

Saudi photo-artist ABDULNASSER GHAREM, whose complex works often involve photography as just one element, is exemplary of this sophistication. Now 41, Gharem taught himself global art history during his formative years. “The Internet appeared in the late ’90s,” he explains. “I started to educate myself from the beginning. In that time, a lot of wars happened in the region. And war affects artists. After the First World War, there was Dadaism, Constructivism; after the Second, the Fluxus movement. I found myself with an opinion, and I wanted to express it.”

These global movements have inspired Gharem to produce art that often speaks primarily to Arab viewers more than it does to western ones. This shows in his elaborate rubber-stamp paintings that often incorporate photographs. “In the Middle East, people suffer from bureaucracy,” he explains. “Nothing happens without the stamps.”

Gharem, who has exhibited at world-leading art fairs including the Venice Biennale and the Sharjah Biennial, has his own ideas about the current interest in photo-art from the Middle East. ”After 9/11, the West and East are more curious to know each other,” he says. “You know why people like art? Usually people get their information about us through the media. But when people see artworks, they can get information from nation to nation. There is nothing in the middle. It’s a pure thing. No one is controlling the artist or his message.” In this regard, Gharem has invested in his beliefs, helping co-found in 2003 the artists’ organization Edge of Arabia, which has since become a leading voice for Saudi contemporary art.

|

| Camille Zakharia, from the “Elusive Homelands” series, “The Awad Family,” 1999-2000. Photo-collage, courtesy of the artist. |

Sophisticated, complex use of multiple media is evident also in the photographic art of Bahrain-based CAMILLE ZAKHARIA, who incorporates elements and materials such as layering, collage and calligraphy. Like Gharem, Zakharia appeared in both the Victoria & Albert and FotoFest shows, and he has mounted dozens of his own exhibitions in North America, Europe and the Middle East. His work, he says, “is introspective in nature. Having left my birthplace Lebanon about 30 years ago, the subjects of home, identity, belonging, sense of self and place remain dear topics.” For example, “Stories from the Alley” is a series he created in 1998 while he was living in Canada. “I had immense nostalgia for the Middle East, and Bahrain in particular. As I listen constantly to [classical Egyptian singer] Umm Kulthum, who is a source of inspiration, I incorporated several of her songs in the backgrounds.”

Photographically, Zakharia cites documentary photographers from outside the Middle East as his leading inspirations, including Eugène Atget, August Sander, Diane Arbus and Alec Soth. “As for my favorite movement,” he adds, “it is Dada, and Hannah Höch in particular.”

Much like Nabil, Zakharia thinks that the Zeitgeist and art infrastructure are propelling Middle Eastern photo-artists. “As the world is opening up to itself, I believe it is also time to discover lesser-known territories,” he muses. “Of course there are other more obvious reasons, including the opening of many galleries and museums in the Middle East and the Gulf states in particular in the last decade, nurturing the creativity of many artists.”

|

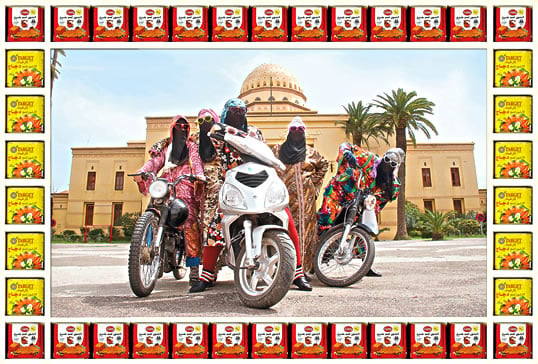

| Hassan Hajjaj, “Kesh Angels,” 2010/1431. Edition of 7. Metallic Lambda print on 3mm white dibond, 101 x 137 cm, courtesy of Taymour Grahne Gallery. |

Like Zakharia and Gharem, Morocco-uk artist HASSAN HAJJAJ appeared in both the London and Houston shows, and he says he has “always been a big fan of all kinds of photography, historic and contemporary, but the photographers who have inspired me the most are Henri Cartier-Bresson, Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso, Robert Capa, David LaChapelle and Shirin Neshat”—a list that ticks off four continents of origin.

As with fellow Moroccan Essaydi, the interplay of “eastern” and “western” elements is fundamental to Hajjaj, fueled by his sensitivity to the exotic ”otherness” with which the outside world has tended to view his homeland.

![“I don’t think of it as mono-structural as ‘photography.’ Most of the artists in the [2014 FotoFest] exhibition cross back and forth among many media ... Like the work, these are artists of the world.” –Wendy Watriss](images/lenses/inset-2.png) “I first turned to photography more than 20 years ago after assisting on [European] photo shoots in Morocco,” he explains. “It felt strange to me that the landscape, cityscape and residents were, perhaps unintentionally, used as an exotic backdrop or props while all the models, clothes, magazine staff and readers were western. No one at the time was really focusing on us.” His work has won wide popularity in part because his responses to this concern often indulge humor and a sense of play along with what might be more dryly called “social commentary.” In each series, he says, “I’ve wanted to show my Morocco—yes, old traditions still exist, but look at how modern and spirited and feisty the characters are!”

“I first turned to photography more than 20 years ago after assisting on [European] photo shoots in Morocco,” he explains. “It felt strange to me that the landscape, cityscape and residents were, perhaps unintentionally, used as an exotic backdrop or props while all the models, clothes, magazine staff and readers were western. No one at the time was really focusing on us.” His work has won wide popularity in part because his responses to this concern often indulge humor and a sense of play along with what might be more dryly called “social commentary.” In each series, he says, “I’ve wanted to show my Morocco—yes, old traditions still exist, but look at how modern and spirited and feisty the characters are!”

Living in the uk and represented by leading galleries there as well as in New York and Dubai, he sees the global interest in Middle Eastern photo-art backed by new regional art infrastructure and aided by the Internet and regional economic prosperity. ”The talent was always there; it’s just that there wasn’t the infrastructure to showcase it,” he says. “You need museums, galleries, art schools, good shippers, good framers, good materials, good publications, magazines, newspapers, reviews, people with disposable income to buy art to support the artists. We take all this for granted in the West.”

![Shirana Shahbazi, “[Komposition-56-2012].” C-print on aluminum, courtesy of Galerie Bob van Orsouw.](images/lenses/M_sp5_by_Shirana_Shahbazi-Kompos_sm.jpg) |

| Shirana Shahbazi, “[Komposition-56-2012].” C-print on aluminum, courtesy of Galerie Bob van Orsouw. |

This new regional art infrastructure, for a decade one of the most rapidly growing in the world, has seen new art galleries, museums, auction houses and art fairs, most visibly in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, but also in Saudi Arabia, where further showcases for contemporary art are in the works. In the older western art centers, the greatest concentration of Middle Eastern photo-art is in London; in the Middle East, the top hub is Dubai, which recently has opened galleries devoted largely and even exclusively to photographic art. The newest is East Wing, whose director, Elie Domit, sees a growth in the general perception of photography from the region. “This awareness and curiosity is part of a shift in attention to a geographic area that has been somewhat shrouded in mystery,” he says.

Rose Issa, a pioneering London gallerist specializing in Middle Eastern contemporary art and editor of the 2011 book Arab Photography Now, holds similar views. “I’ve found there is a thirst for images from or about the region as few people today can very easily go to Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Tunisia, Egypt, Iran or Saudi Arabia, and, therefore, representation by artists from the area can bridge the gap,” she says. “Also, once a region is in the news, it is natural for the public to want to learn more about it, and the artist-photographers from the Middle East and North Africa all have a lot of unique and interesting things to say.”

|

| Ziad Antar, “Burj Khalifa III,” from the “Expired” series, 2012. Silver print, courtesy of Selma Feriani Gallery. |

Yet there are other, far more practical reasons, she explains: “In the last 20 years, photography in general—not just from the Middle East—has been popular with art galleries. The reasons for this are not only artistic, but also logistic: Photography is a medium that can easily avoid transportation costs. Photographers can send images by email or on a disc, so it is less costly to organize a show once you subtract shipping costs, and the size of the image can be adapted to suit your budget, therefore saving on framing costs.”

So it appears that the flowering of photographic art from the Middle East has had multiple seeds. Its time is here, fueled by new money and venues for showing and disseminating work, from museums and galleries and art fairs to online.

But perhaps the greatest factor is the increasingly global outlook of the Middle Eastern photo-artists themselves. By absorbing life, culture and art history beyond their regions of origin and through the lenses of both their cameras and of their own experience, they are putting their original stamp on the global art scene.

|

Simon Bowcock is a uk-based photographic artist who writes regularly about art for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar Art and Eikon. |