he “global economy” of the Middle Ages was created by linking the Indian Ocean trading networks with those of the Mediterranean Sea and its African and European hinterlands. By the eighth century, Spain and the African shores of the Mediterranean were part of the expanding empire that Muslims called dar al-islam (“the house of Islam”) and had commercial links, both maritime and overland, with Egypt and Syria. Between the years 800 and 1000, the Mediterranean was dominated by Muslim shipping.

he “global economy” of the Middle Ages was created by linking the Indian Ocean trading networks with those of the Mediterranean Sea and its African and European hinterlands. By the eighth century, Spain and the African shores of the Mediterranean were part of the expanding empire that Muslims called dar al-islam (“the house of Islam”) and had commercial links, both maritime and overland, with Egypt and Syria. Between the years 800 and 1000, the Mediterranean was dominated by Muslim shipping.

|

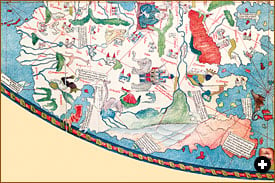

| Following the season of northeast monsoon winds that carried them from India or places farther east, spices, textiles and other goods arrived at Alexandria via Aden and Jiddah. European traders—mostly from Venice—timed their own arrival in Alexandria accordingly. BUKHARI COLLECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS OF ARABIA |

The Fatimid Dynasty arose in what is now Tunisia in the early 10th century. Their subsequent invasion of Egypt gave them control of the most important port of the eastern Mediterranean: Alexandria. This famous port linked the new Fatimid capital of Cairo, founded in 969, to the whole Mediterranean world via the Nile. With the conquest of Egypt, the Fatimids made a concerted drive to shift the economic center of the Islamic world from Baghdad, capital of their political rivals, the Abbasids, to Cairo. They revived the Red Sea as the principal conduit of maritime trade with the Indian Ocean, restoring that route to the role it had played in Ptolemaic and Roman times.

It was during the Fatimid period (909–1171) that the European economy began to recover from the barbarian invasions that had put an end to the Roman Empire. European courts began to demand the goods that the Indian Ocean trading networks supplied to Alexandria and Constantinople. These products, together with ceramics, textiles and sugar from Egypt and Syria, reached European markets almost exclusively through the Italian maritime republics of Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa and Venice. By the 15th century, Venice had eclipsed its competitors and established a virtual monopoly of the eastern trade, leaving Genoa to concentrate on trade with Spain, North Africa and the Black Sea.

|

| Left: Venice struck its first gold ducat in 1282. Within 150 years Venetian ducats had become a widely used currency in much of the Middle East. Center: Muslim rulers had been minting gold dinars since the late seventh century; this one was issued in the mid-13th century by al-Musta‘sim, the last Abbasid ruler of Baghdad. Right: This silver dirham was struck at Sivas, in today’s Turkey, in 1241 or 1242. BRITISH MUSEUM / HERITAGE IMAGE PARTNERSHIP (HIP) / IMAGE WORKS; BRITISH MUSEUM / HIP (2) |

Synchronized to the clock-like regularity of the monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean was the equally regular sailing of the Venetian convoys, the mude, which set out toward the end of August and made their way slowly through the Adriatic and the Aegean to Cyprus and Alexandria, timing their arrival there to coincide with the availability of monsoon-borne goods from the East, and returned to Venice 11 months later. The economies of northern Europe were similarly linked—indirectly, like a train of interlocking gears—to the Indian Ocean monsoon: From Venice, after the return of the mude, spices and textiles traveled overland and by internal waterways to the trade fairs of northern Europe. (Another set of gears driven by the monsoon linked the Indian Ocean economies with China.)

In 1204, Venice led the Crusader conquest of Constantinople. A few years later, a commercial treaty with the Mamluk sultan, ruler of Egypt and Syria, gave the Venetians a virtual monopoly of trade at Alexandria, Tripoli and Beirut. Toward the middle of the 14th century, the number of mude was doubled.

Until the ninth century, Venice had been part of the Byzantine Empire, and it never lost its half-oriental quality. Just as the physical city seems to float magically on the surface of the lagoon, belonging neither to land nor sea, Venice did not seem to fully belong to the European world in which it was tenuously anchored. Here was a city devoted entirely to trade, with the full apparatus of money, banks, credit and letters of exchange—all uncanny mysteries to most of northern Europe. The Venetian capacity to transform humble products like salt, grain and cloth into gold was to outsiders a kind of alchemy.

Roman Gold, Persian Silver

Cosmas Indicopleustes (“Cosmas the Traveler to India”), who wrote soon after AD 547, tells the story of a Roman merchant from Egypt named Sopatro who met the Persian ambassador at the court of one of the kings of Sri Lanka. “Which of your kings is the richest and most powerful?” asked the king. “Ours is the most powerful, magnificent and rich,” answered the Persian ambassador. “And you, Roman, what do you have to say to that?” asked the king. Sopatro answered, “If you want the truth, you have both kings right here. Look at each and see for yourself which is the most brilliant and powerful.” “What do you mean: I have both kings before me?” asked the king. “You have both their coins,” answered Sopatro. “You have the nomisma of one and the drachma of the other. Look at both and know the truth.” The king ordered both coins to be brought. The Egyptian nomisma was of pure gold, splendid and beautiful; the Persian drachma was of silver and, to tell the truth, could not compare with the gold piece. The king, after looking carefully at both sides of each coin, praised the nomisma and said, “In truth, the Romans are splendid, powerful and wise.” |

The famous Venetian Arsenal, immortalized by Dante in Canto XXI of the Inferno, was the largest industrial site in Europe. Galleys were built and fitted out on an assembly-line basis that seemed little short of miraculous to visitors. Pero Tafur, a Castilian nobleman who visited the city in 1438, was astonished to see 10 galleys readied for sea, fully crewed, provisioned and armed, in three hours flat.

He was equally astonished to find Spanish fruit for sale in Venice as fresh and cheap as at home. The markets were full of goods from Syria too, he wrote, and even from India, “since the Venetians navigate all over the world.” But the Venetians of course did not sail to India: The spices and textiles in Venice had come from Alexandria, shipped there from India and points east via Aden and Jiddah.

Venice had long dreamed of breaking the Muslim monopoly of the Indian Ocean trade. A hundred years before Pero Tafur’s visit, the Venetian traveler Marin Sanuto put forward a plan to outflank Egypt and seize control of the Indian Ocean trade by launching ships in the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf. Although impractical, his plan nevertheless reveals the overweening confidence and ambition of the Venetian Republic.

As a maritime republic dedicated to international trade, Venice was an anomaly in a feudal Europe that measured wealth by land, not money. In 1423, as the Doge Tommaso Mocenigo lay dying, he wrote in his last testament: “If you heed my advice, you will find yourselves masters of the gold of the Christians; the whole world will fear and revere you.” He was stating the obvious: Venice functioned on gold. It was gold that bought their cargoes, gold that supplied their city with grain, gold that built their ships. Sooner or later, the gold of northern Europe and Africa found its way to Venice.

The Venetian gold ducat, first issued in 1282, was of exceptional purity and was eagerly sought throughout Europe and the East. The year before Mocenigo died, the Arab chronicler al-Fasi could write: “In our time the Venetian ducat has invaded the major cities of the world: Cairo, the whole of Syria, the Hijaz and Yemen, to the point that it has become the most commonly used currency.” The ducat undoubtedly voyaged to India long before the Portuguese.

|

| Left: Through Alexandria flowed much of the Europe-bound Indian Ocean trade that came north up the Red Sea. Constantinople, right, handled much overland Silk Roads trade, as well as maritime trade that came up through the Arabian Gulf and traveled overland through Syria. ALEXANDRIA: CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY (DAPPER, NAUKEURIGE BESCHRIJVINGE…, 1668); CONSTANTINOPLE: BUKHARI COLLECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS OF ARABIA (SPEED) |

“Gold equals fear plus respect” is a peculiarly Venetian equation. In the feudal world, fear and respect were attributes of kingship. The power of the ruler was derived from his lands and the number of men he could mount. Venice, which had neither king nor lands, made do instead with the king of metals, to which the traditional fear and respect were transferred.

In the Islamic world, gold and silver currency had been issued since 691, when the first dinar was struck at Damascus. Both the coin and the word derived from the Byzantine denarion, just as the Islamic silver coin, the dirham, was based on the Byzantine drachme. Gold dinar and silver dirham together formed the bimetallic monetary system that Muslim writers referred to as al-naqdayn, “the two coins.”

In the Islamic world, gold was a tool. Mocenigo’s equation, in which fear and respect could be had for gold, would have sounded blasphemous to Muslims, for whom it is God alone who commands fear and respect. Muslims believed that gold and silver must circulate, and this circulation, called rawaj, was a social and religious duty. Hoarding gold and silver was forbidden by the Qur’an: “Those who store up gold and silver and do not spend them in the way of God, tell them of a painful chastisement!” The cosmographer al-Qawini, writing only a decade or so after the minting of the first florin, says:

Gold is the noblest of the blessings of Almighty God upon his servants, for it is the foundation of the affairs of this world and brings order to the affairs of mankind…. With silver and gold coins, everything can be bought and sold. They must circulate, unlike other forms of wealth, for it is not desirable for anyone to accumulate silver and gold…. Anyone who stores them up destroys the wisdom created by God, just as if one imprisoned the qadi of a town and prevented him from carrying out his duties toward the people.”

On the eve of the Islamic conquests in the early seventh century, however, there was a large and powerful state in which gold, the regulator of the affairs of men, was imprisoned. This was Sasanian Persia. Luxury goods from India, Southeast Asia and China passed through Sasanian hands on their way to Byzantium, but the gold the Byzantines paid for them never returned. The Sasanians themselves only circulated silver.

The Arab conquest of Persia thus released huge quantities of gold into the world economy, first in the form of booty, then in the form of taxes levied in gold. Still more gold was obtained from the church treasuries in conquered Byzantine territories and from taxes levied on the non-Muslim population. And astounding quantities were obtained from the systematic looting of pharaonic tombs in Egypt, a practice that went on for more than a millennium.

The Arab conquest of Persia thus released huge quantities of gold into the world economy, first in the form of booty, then in the form of taxes levied in gold. Still more gold was obtained from the church treasuries in conquered Byzantine territories and from taxes levied on the non-Muslim population. And astounding quantities were obtained from the systematic looting of pharaonic tombs in Egypt, a practice that went on for more than a millennium.

The release of this flood of gold was comparable to the release of the Aztec and Inca gold hoards at the hands of the Spanish conquistadors eight centuries later. Just as the incredible wealth of Mexico and Peru quickly evaporated and forced the Spaniards to look for new sources of precious metals, so the supplies of “old” gold in the victorious Muslim empire soon needed to be supplemented.

There were a number of sources: Russia, Central Asia beyond the Oxus River, Af-ghanistan, western Arabia (the Hijaz) and the famous Egyptian mines of Wadi ‘Allaqi south of Aswan. But by far the richest were in Africa south of the Sahara, the area the Arabs called bilad al-sudan, “the land of the Blacks.” Alluvial gold was found along the upper reaches of the Senegal and Niger rivers, and along the Guinea coast. These areas, together with gold-bearing regions in southeastern Africa near Sofala, were so productive that by the 14th century Africa was supplying as much as two-thirds of the world’s gold.

How the Monsoon Works

The word “monsoon” comes from the Arabic mawsim, meaning “season.” In Arabic, mawsim refers to the period of time in which ships could safely depart from port, as in mawsim ‘adani, “the season of Aden.” Collectively, these times were called mawasim al-asfar, “sailing seasons.” The regular periods of northeast and southwest winds that we call the monsoon are called by the Arabs rih al-azyab and rih al-kaws, respectively.

While there are monsoon systems that affect parts of North America, Central America and northern Australia, the largest is found in the area of the Earth’s largest landmass: the Indian subcontinent and eastern Asia. Generally speaking, monsoon systems are powered by the seasonal warming and cooling of very large continental air masses, and depend on the fact that temperatures over land change faster than temperatures over oceans.

From the spring equinox through summer, warming air over southern Asia rises, drawing in toward land the relatively cooler and more humid ocean air. This creates southwest winds heavy with moisture. As the ocean air warms and rises in turn, the moisture condenses, resulting in the torrential monsoon rains.

From the fall equinox through winter, the system reverses as relatively warmer ocean air rises, drawing after it the relatively cooler dry air above the land. This creates northeast winds with cool, sunny and dry weather.

From mid-March, traders knew, the prevailing wind blew from the southwest, and the last ships left Yemen eastbound for India by mid-September, so they could complete their voyage before the northeast monsoon began. Westbound, the first ships left western India for Yemen on October 16, arriving—if all went well—a mere 18 days later. If departure and arrival dates were carefully enough calculated, the turnaround times could be very short.

Each sailing season was divided into two major periods, one at the beginning, called awwal al-zaman, “first of the season,” and one at the end, called akhir al-zaman, “last of the season.” Each offered an advantage: The convoys that left during the first of the season found the readiest markets, and those that left at the last had the shortest turnaround time.

Of the two monsoons, the southwest was the more dangerous. In June and July, heavy swells and the famous torrential rains closed the ports of western India. The northeast monsoon, on the other hand, beginning in August in western India, meant clear sailing with steady winds and few squalls. Because it arose on the mainland, it carried little or no rain, and could be sailed with ease throughout its season. |

Overland contact between the North African coast and sub-Saharan Africa probably dates back to the days of the Phoenicians. The introduction of the camel to North Africa in Roman times made regular trade across the Sahara economically viable, but it was not until the foundation in 747 of the caravan city of Sijilmasa, in southern Morocco, that the gold trade with the south came to be organized on a regular basis.

This was cheap gold. The lands south of the Sahara had no salt, and men suffering from salt deficiency were willing to trade gold for an equal weight of salt. The resulting trans-Saharan trade led to the rise of powerful African kingdoms in the south.

One of the largest was the Mandingo kingdom of Mali, whose rulers seem to have become Muslims sometime during the first quarter of the 12th century. At its height, the kingdom stretched from the Atlantic to the upper Niger. The arrival of the Mandingo ruler Mansa Musa in Cairo in 1324, on his way to Makkah to perform the pilgrimage, caused a sensation. He crossed the Sahara accompanied by thousands of followers and 100 camel-loads of gold attended by 500 slaves—each bearing a golden staff weighing nearly three kilograms (6 lb). Mansa Musa spent so lavishly in the markets of Cairo that the price of gold fell and took years to recover. Stories of his fabled wealth reached Europe.

African gold attracted merchants from Portugal, Spain, Majorca, France and Italy, all of whom had traded with North African ports since the 10th century. In the 12th, the Genoese sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar and began trading with the towns on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. In 1253, the year after the first gold coins were struck in Genoa and Florence, they established a trading station farther south in Safi, where they perhaps first learned of the gold-producing lands south of the Sahara.

These European merchants funneled African gold into the rapidly monetizing European economy. Just as in Roman times, both silver and gold then flowed eastward to pay for imported luxuries, ultimately reaching India and China.

The gold that flowed to India never returned. It was hoarded, in the form of temple treasure or jewelry, rather than circulated. Just as Sasanian Persia had been, India was the graveyard of gold. It was just the opposite in China. Gold held no monetary value to the Chinese, and China always exchanged gold for silver at an advantageous rate, thus draining silver from the world economy. Although it did not serve as currency—the standard currency was copper “cash”—China absorbed vast quantities of silver, which was used as bullion for major payments. And because China paid for her imports with silks and ceramics, silver rarely left the Chinese empire, except as the result of invasion from the western steppes and, in the late 18th century, British insistence that China should pay for opium with silver. Just as India was the graveyard of gold, China was the graveyard of silver.

![A detail from a 1572 engraving of Venice shows the city’s famous arsenal with its shipbuilding assembly line. “In the Venetians’ arsenal…boils through wintry months tenacious pitch,” wrote Dante. “One [workman] hammers at the prow, one at the poop, this shapeth oars, that other cables twirls, the mizzen one repairs, and mainsail rent.”](images/MONSOONS_2_56604.jpg) |

| A detail from a 1572 engraving of Venice shows the city’s famous arsenal with its shipbuilding assembly line. “In the Venetians’ arsenal…boils through wintry months tenacious pitch,” wrote Dante. “One [workman] hammers at the prow, one at the poop, this shapeth oars, that other cables twirls, the mizzen one repairs, and mainsail rent.” BRAUN AND HOGENBERG, CIVITATES ORBIS TERRARUM, 1572 (DETAIL) |

In fact it has been estimated that between a third and a half of all the silver produced in Mexico and Peru found its way to China. Between 1531 and 1660, the fabulous mines of Zacatecas and Potosí officially sent 16,887 tons of silver to Spain; unofficially, that figure should probably be doubled to include contraband and private exports. Although small by modern standards—world silver production reached 16,117 metric tons in 2004 alone—it was a huge amount for the pre-modern world economy to absorb. A great deal of it went to India too: The coins of the Mughal rulers of India were minted from New World silver. In the late 16th and 17th centuries, the Spanish piece of eight, prototype of the dollar, circulated throughout Asia, finally ending its journey in the Celestial Kingdom. The piece of eight, containing 25.5 grams (about 3/4 oz) of pure silver, had become the first global currency, used in all of the New World, Europe and Asia.

This flow of precious metals from West to East is a constant of pre-modern world history. From classical times until the late 18th century, the West had a trade deficit with the East. The imbalance was caused by the failure of European products and manufactured goods, with a few exceptions, to find buyers in the East. Sir Thomas Roe, ambassador to the Mughal court in the 17th century, was chagrined to discover that Indian craftsmen took no more than a day to reproduce the fine gifts, including paintings, that he had brought to the emperor. European merchants who wanted the textiles, ceramics, metalwork, dyestuffs and spices of the Islamic world generally had to pay cash.

The Mediterranean trading network, led by the commercial republics of Italy, was thus driven to a constant search for new supplies of silver and gold. It was this search that led to the Portuguese exploratory expeditions down the west coast of Africa in the 15th century, journeys that culminated in 1498 in Vasco da Gama’s discovery of the sea route to India. It was the search for gold that led Columbus to seek an Atlantic route to Japan and China, lands he mistakenly believed to be rich in gold. It is one of the ironies of history that instead he discovered a new world, richer in precious metals than the old.

Gold is incorruptible, a metaphor for purity and eternal life. It seemed logical to the men of the Middle Ages that this purest of metals should abound in, or near, the Earthly Paradise, which scripture placed in the East, where the sun rose. Four rivers flowed from the Earthly Paradise and one of them was the Nile. Then what easier way to reach the Earthly Paradise than to follow the Nile to its source? Rumors of a great river in sub-Saharan Africa had circulated since antiquity, and it was logical to suppose that this must be the Nile. As the Portuguese explorers moved down the western African coast, they identified each of the great rivers they encountered—the Senegal, the Niger and the Congo—in turn with the Nile, eagerly questioning local people about the lands where each river arose.

Gold is incorruptible, a metaphor for purity and eternal life. It seemed logical to the men of the Middle Ages that this purest of metals should abound in, or near, the Earthly Paradise, which scripture placed in the East, where the sun rose. Four rivers flowed from the Earthly Paradise and one of them was the Nile. Then what easier way to reach the Earthly Paradise than to follow the Nile to its source? Rumors of a great river in sub-Saharan Africa had circulated since antiquity, and it was logical to suppose that this must be the Nile. As the Portuguese explorers moved down the western African coast, they identified each of the great rivers they encountered—the Senegal, the Niger and the Congo—in turn with the Nile, eagerly questioning local people about the lands where each river arose.

These geographical misconceptions were extraordinarily fruitful. Without them, it is doubtful the Portuguese would ever have begun the punishing series of expeditions around Africa that finally led to the sea route to India. The myth of the Earthly Paradise had a powerful political dimension as well. It was widely believed in Europe that somewhere near the Earthly Paradise lay the realm of a Christian monarch named Prester John. When the legend first arose in the 12th century, his kingdom was located in Asia, and is so marked on some maps.

Closer acquaintance with Asia, the result of the travels of men like Marco Polo and William of Rubruck, did not put an end to the legend of Prester John. Instead, his realm was displaced to lesser-known lands, first to India, then to Africa. Pilgrims had learned from Ethiopian priests in Jerusalem of the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, and in 1481 a mission from Ethiopia somehow found its way to Lisbon. Not long afterward the Portuguese King João II dispatched an expedition up the Senegal River, which he identified with the Nile, searching for the land of Prester John. This was not the first such expedition. When the Venetian explorer Ca’ da Mosto reached the Cape Verde Islands in 1456, sailing under Portuguese auspices, he had reported that he had heard that the realm of Prester John lay 300 leagues into the African interior. How hearts must have leapt in Lisbon! All that was needed was to make contact with Prester John and his army, and the Islamic world would be outflanked and the Muslim monopoly of the eastern trade at last broken.

|

| A map dating from 1447 shows that the true shape and extent of Africa was still unclear to European navigators in the mid-15th century. The larger red area is the Red Sea. BIBLIOTHEQUE DES ARTS DECORATIFS / ARCHIVES CHARMET / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

Legend, politics and economics were intimately intertwined. In 1487, the same year Bartolomeu Dias set off on his epoch-making voyage around the Cape, King João sent the Arabic-speaking Pero de Covilhã overland to search for the kingdom of Prester John. He visited Makkah, gathered information on trade in the Indian Ocean, sailed down the East African coast as far south as Sofala and eventually made his way to Ethiopia. He had found the land of Prester John, but, sadly, it was not the Earthly Paradise. This disappointment was palliated by a single fact which he reported back to Portugal by messenger before his 30-year captivity in Ethiopia: It was possible to reach India by sailing around Africa. He could only have learned a geographical fact of such overwhelming importance from Indian Ocean sailors, probably in Sofala. His report reached the Portuguese court and confirmed Dias’s discovery. And incidentally, it showed that the true shape of Africa was known to the Arabs before Vasco da Gama’s voyage.

Men had speculated on the true shape and extent of Africa since the days of Herodotus in the fifth century BC, and though Herodotus himself is the source of two accounts of the circumnavigation of Africa, later Greek writers uniformly dismissed both as fantasy. They followed Aristotle and Ptolemy, who believed that Africa was joined to Asia somewhere east of India, making the Indian Ocean a landlocked sea like the Mediterranean. This view, with some modifications, became geographical orthodoxy for medieval scholars in both Europe and the Islamic world.

Toward the end of the 13th century, advances in shipbuilding and navigation nourished Europeans’ curiosity about what lay beyond the Pillars of Hercules. The round ship, adopted from Atlantic shipbuilders, and the compass, introduced by the Arabs from China, made Atlantic voyages possible. In 1291, two brothers from Genoa, Ugolino and Vadino Vivaldi, passed through the Pillars of Hercules and voyaged south down the West African coast, “volentes ire in Levante ad partes Indiarum” (“desiring to go east, to the regions of India”). It was the first recorded attempt to circumnavigate Africa since antiquity. This single phrase from the chronicle recording their voyage could serve as the motto for the history of European maritime expansion.

The Vivaldi brothers vanished at sea. What is remarkable about their voyage is that they thought they could reach India by sailing around Africa. Why did they think this was possible?

Barter and the Monetary Frontier

On the west coast of Africa, the coastal settlements of the Portuguese, beginning in 1455 with São Jorge da Mina, traded for gold from the remote interior, where tribes mined it and exchanged it by barter for salt, cloth and trinkets. On the east coast of Africa, the gold was bought in the interior by intermediaries, also through barter, and then brought to the Arab merchants at the port of Sofala. In both places, it was rumored that the tribesmen who dug the gold from the ground were cannibals. The same stories were told throughout the Indonesian archipelago. Barter and reputed cannibalism apparently marked the limits of the Mediterranean–Indian Ocean monetary economy. Even peoples who lay beyond the linguistic and monetary boundaries of the expanding world economy were its silent partners. These frontiers between monetary and non-monetary economies coincided with the shifting boundaries between the known and the unknown, both geographical and cultural. |

One of the few Muslim scientists to challenge geographical orthodoxy was al-Biruni, who wrote in the later 10th century. This great scientist, in one work, stated quite categorically that no one could sail the sea south of Sofala on Africa’s east coast, and that no one foolish enough to try had ever returned. Yet in another work, meditating on a story he had read in al-Mas‘udi of the discovery in the Mediterranean of a carved plank from an Indian Ocean vessel, al-Biruni concluded that it could only have come there by drifting around Africa—and indeed a sketch map in one of his works clearly shows Africa as a peninsula.

A similar story occurs in the accounts of the Roman geographer Strabo, so both the Arabic and the classical sources contain two diametrically opposed views of the shape of Africa. In the “non-Ptolemaic” tradition, found in the earliest Arab geographers, the ocean surrounded the world, and hence the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean were one and the same body of water. The Ptolemaic tradition had the eastern shore of Africa joined to China.

There was an almost uncrossable divide between the theories of the geographers and the practical experience of the seamen who sailed the Indian Ocean. It only began to be bridged in the 15th century, when the Arab navigator Ahmad ibn Majid codified the experience of a lifetime navigating the Indian Ocean and the lower reaches of the Red Sea in a series of remarkable works. In one of these, the Kitab al-Fawa’id fi Usul ‘Ilm al-Bahr wa’ l-Qawa’id (The Book of Useful Information on the Principles and Rules of Navigation), written about 1490, he describes the possibility of circumnavigating Africa from east to west as if it were common knowledge.

Ibn Majid names the major East African ports from Mogadishu to Sofala and then says, “When you reach Sofala you pass the island of Madagascar on your left, separated from the coast on your right. There the land turns to the northwest, where the regions of darkness begin…. Then you come to the coast of the Maghrib, which begins at Masa…. When you have passed Masa, you come to Safi…. Now you have reached the Moroccan coast. You then enter the Strait of Ceuta, the entrance to the Mediterranean.” The route is described in a clockwise direction, showing the writer’s Indian Ocean orientation. It is clear that toward the end of the 15th century, outside conventional learned circles, new information about the true shape of Africa was beginning to circulate.

|

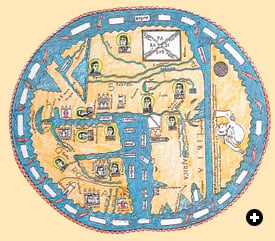

This early 13th-century “Beatus” map, with south at the top, locates the Earthly Paradise in Southeast Asia. From it flow the four major rivers of the world—often identified as the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates and Ganges—which all flowed through Muslim lands. KAY CORCORAN / ORIAS / UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY (SUAREZ: EARLY MAPPING OF SOUTHEAST ASIA, PERIPLUS, 1999)

|

Two far-off events at the beginning of the 15th century had profound repercussions in the Indian Ocean: the Portuguese capture in 1415 of Ceuta, on the Moroccan coast opposite Gibraltar, and the death in 1405 of the Central Asian conqueror Tamerlane (Timur). Ceuta was the port from which the Muslim invasion of Spain had been launched in 711; its capture marked the beginning of the Portuguese push around Africa that culminated in the discovery of the sea route to India.

Azurara, the official chronicler of the capture of Ceuta, painted a glowing picture of the town, which he called “the key to the whole Mediterranean Sea.” The city astonished the Portuguese soldiers, who were amazed at its fine houses, the gold, silver and jewels in the markets and the cosmopolitan population. They saw men “from Ethiopia, Alexandria, Syria, Barbary, Assyria…as well as those from the Orient who lived on the other side of the Euphrates River, and from the Indies.” Azurara clearly states that one of the motives of the expedition was to seize control of the African gold trade: Forty years later, with the establishment of the fortress of São Jorge da Mina on the Guinea coast, 25 to 35 percent of the gold that had formerly made its way across the Sahara to North African markets and to Mamluk Egypt now passed into the hands of the Portuguese instead.

|

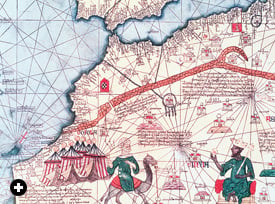

| Mansa Musa, shown crowned at right, was the ruler of the vast Mandingo kingdom of Mali. From the mines of West Africa he amassed legendary amounts of gold, which his subjects traded for salt, weight for weight. This is a detail from the Catalan Atlas, which was produced in 1375. Note how abruptly the mapmakers’ knowledge of the details of the African coast ends. ABRAHAM CRESQUES / BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

In Asia in the late 1300’s, the armies of Tamerlane, a descendant of Genghis Khan, swept over Iran, Iraq and Syria. The major cities of the Islamic heartlands were destroyed with great loss of life. To the east, Delhi was sacked in 1398, and China was spared only by Tamerlane’s death. The overland Silk Roads from China to the West were disrupted as the cities they had linked were destroyed. Concerned at the disruption of their overland export trade and anxious to explore maritime alternatives, the Chinese in 1402 sent an embassy to the newly founded city of Malacca, in what is today Malaysia, a port that would grow to be the linchpin of trade between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. In 1405, the year Tamerlane died, the Ming emperor of China dispatched the first of seven great argosies to the Indian Ocean under the admiral Zheng He.

At the same time that the vast Chinese fleets crossed and recrossed the Indian Ocean, Muslim sultanates began to appear in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. Ahmad ibn Majid composed his navigational works and, in the West, European ships sailed into the Atlantic. The simultaneity of this sudden burst of maritime activity is fascinating. The Orient was reaching out to the Occident at the very time the Occident was “desiring to go east, to the regions of India.”

|

Historian and Arabist Paul Lunde studied at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and specializes in Islamic history and literature. He is the author of Islam: Culture, Faith and History. With Caroline Stone, he has translated Mas‘udi’s Meadows of Gold and—forthcoming this fall from Penguin—Travellers From the Arab World to the Lands of the North, a collection of travel accounts. Lunde is a longtime contributor to this magazine, with some 60 articles to his credit over the past 33 years, including special multi-article sections on Arabic-language printing and the history of the Silk Roads, and the theme issue “The Middle East and the Age of Discovery” (M/J 92). He lives in Seville and Cambridge, England, and is working on an Internet project to map pre-modern Eurasian cultural and intellectual exchanges. He can be reached at paullunde@hotmail.com. |

< Previous Story | Next Story >