n 1500, the year Ahmad ibn Majid wrote his last poem on navigation and the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral touched four continents, the balsam trees of Matariyyah, just outside Cairo, inexplicably withered away.

n 1500, the year Ahmad ibn Majid wrote his last poem on navigation and the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral touched four continents, the balsam trees of Matariyyah, just outside Cairo, inexplicably withered away.

|

| A 19th-century portrait of Vasco da Gama, who may have spent his 30th birthday on his epoch-making voyage around Africa to Goa. BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

The Coptic Christians said they had been planted by Mary during her sojourn in Egypt. The Mamluk chronicler Ibn Iyas wrote that “Europeans from many different countries used to come to obtain the oil of the balsam tree, and paid fantastic prices for it…. So the species disappeared…as if it had never existed, and this was an extraordinary thing, for it had been one of the most famous plants of the region since remote antiquity.”

The little balsam garden symbolized the traditional commercial relationship between Islam and Christendom, a relationship that was changed forever by the voyages of Vasco da Gama and Cabral. It was a relationship that had always been carried out on Muslim terms. Here was a commodity of legendary rarity, produced only in this one place, to which miraculous curative powers were ascribed. Production was severely limited: Planting, collection and processing of the balsam were carried out by Coptic monks under the aegis of the Islamic state. The balsam was sold only to favored trading partners such as the Venetians, whose presence in Islamic ports was strictly governed by treaty. For Ibn Iyas, the ominous withering of the balsam trees meant the end of a familiar world.

When Vasco da Gama set out from Lisbon in 1498, the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria dominated the Middle East. They controlled the key Mediterranean ports of Alexandria, Beirut and Tripoli as well as all of the Red Sea and the overland routes to Makkah. The spices of India and the East Indies reached Venice through Mamluk territory, and taxes on the trade provided a significant part of Mamluk revenues. For more than 200 years the Venetians and the Mamluks had maintained diplomatic and commercial relations, and their prosperity was interdependent. The Portuguese intrusion into the Indian Ocean was a direct blow to the commercial interests of Venice, and the Venetians did everything they could to encourage the Mamluks to repel the Portuguese.

Yet the Mamluk regime was on its last legs. A new power had risen in the Middle East: the Ottoman Turks. In 1453 they conquered the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, putting an end to the last Christian power in Asia. The Ottoman sultan Selim the Grim took Mamluk Syria in 1516, and the following year decimated the Mamluk cavalry of Egypt—which refused to use firearms—with cannon and arquebuses. The age of the gunpowder empires had dawned.

With victory came mastery of the Red Sea and the trade with the East. The Ottomans inherited the custodianship of the Holy Cities of Makkah and Madinah and the pilgrimage routes. This meant protecting Red Sea shipping from the Portuguese.

With victory came mastery of the Red Sea and the trade with the East. The Ottomans inherited the custodianship of the Holy Cities of Makkah and Madinah and the pilgrimage routes. This meant protecting Red Sea shipping from the Portuguese.

When Cabral returned to Lisbon on July 31, 1501, with a cargo of spices and a shipload of gold from Sofala, the Venetians were filled with dismay. “This,” says a Venetian chronicler, “was considered very bad news for Venice…. Truly the Venetian merchants are in a bad way.”

The Mamluks in Egypt were just as worried. In 1498, the year Vasco da Gama set out for India, so much pepper was available in the markets of Alexandria that the Venetians could not raise enough money to buy it all. In 1502, four years later, there was not enough pepper to load their ships. They were forced to reduce the number of galleys in their merchant fleet from 13 to three, and instead of sending two annual mude to Alexandria thereafter, as had become the custom in the 15th century, Venice sent only one fleet every two years.

The interests of the Venetians and the Mamluks thus coincided. Venetian embassies to Cairo urged military action, and promised arms and men. The Mamluk sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri began to construct a fleet of 12 ships at Suez, using timber imported from the Mediterranean. The ships were manned largely by sailors from the North African coast, along with some Venetian mercenaries. While the fleet was being constructed, emissaries arrived from Malik Ayaz, the governor of the Gujarati port of Diu, promising further military aid against the common enemy.

|

| Lisbon was neither large nor prosperous when the Portuguese began their 80-year push around Africa, yet by the time this engraving was made in 1572, it had grown wealthy on its new monopoly of Europe’s route around the Cape of Good Hope to the Indian Ocean. BRAUN AND HOGENBERG, CIVITATES ORBIS TERRARUM, 1572 (DETAIL) |

Constructing and manning a fleet to sail from Suez to India was a long, expensive and laborious task. While it was under way, the Portuguese were carrying out a concerted naval strategy aimed at capturing—by force or by treaty—the major Indian Ocean ports with the goal of shattering the Muslim monopoly of the carrying trade in the western Indian Ocean.

In 1500 the Portuguese crown had sent its second expedition to India, captained by Cabral. He was accompanied by Bartolomeu Dias, the explorer who first sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in 1487. The 13 ships were well armed, for Vasco da Gama’s report on his reception in Calicut had convinced the crown that the Indian Ocean trading network could only be penetrated by force. But not much force, because da Gama had also reported an extraordinary fact: Indian Ocean merchant shipping was unarmed.

Not so in the Mediterranean, where commerce and coercion had always gone hand in hand. The Italian merchant republics of Genoa and Venice waged their commercial wars at sea; Catalans, Majorcans, Maltese, Spaniards and French competed for markets and maritime routes by force of arms. By the middle of the 15th century, cannon were mounted on the great Venetian galleys, and other powers followed suit. Ships with superstructures strong enough to bear cannon were constructed, resulting in the galleons, the floating fortresses of the 16th century.

By later standards, the Portuguese ships that rounded the Cape of Good Hope were lightly armed. Their cannon barrels were forged of iron rods, capable only of firing stones weighing fractions of a kilogram a couple hundred meters. They nevertheless proved effective against the unarmed shipping of the Indian Ocean. Although it is unlikely that Cabral’s two-day bombardment of Calicut caused much actual damage, the psychological effect was enormous.

The Portuguese also quickly took advantage of local rivalries. Although unable to establish a warehouse in Calicut, Cabral found rivals of Calicut at Cochin and Cananore who were prepared to deal with the Portuguese.

The third Portuguese expedition, in 1502, was composed of 14 ships, again commanded by Vasco da Gama. He stopped at Kilwa on the East African coast, where he levied a yearly tribute of 1500 ounces of gold from the sultan. When he reached Calicut, he too bombarded the port, in retaliation for the killing of the Portuguese traders he had stationed there on his first voyage. The Muslims of the Malabar coast mounted a fleet against him, but they were defeated by the Portuguese cannon. It was on this trip that da Gama sank a pilgrim ship, the Meri, drowning all 300 passengers.

He returned to Lisbon with a large cargo of spices from Cochin, and King Manuel made the decision to establish a permanent naval presence in the Indian Ocean in order to gain complete control of the spice trade. He took the grandiloquent title “Lord of the Conquest, Navigation and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India.” In fact, Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India were never conquered, and the Portuguese never fully succeeded in monopolizing the commerce of the Indian Ocean. What they did monopolize, for almost 100 years, was the Cape route to India.

|

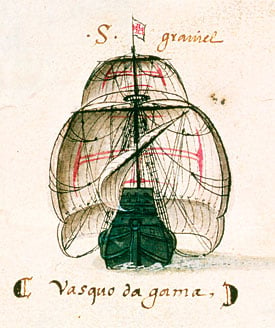

| Vasco da Gama’s ship, under full sail and with a following wind, was illustrated in the Libro das Armadas in 1497. ACADEMIA DAS CIENCIAS DE LISBOA / GIRAUDON / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

In 1505, Francisco de Almeida, appointed viceroy with a tenure of three years, was sent with 21 ships to establish fortresses at key locations and above all to deny Muslim shipping access to the Red Sea, so that “they are not able to carry any spices to the territory of the [Mamluk] sultan and everyone in India would lose the illusion of being able to trade with anyone but us.”

Almeida had fought at the siege of Granada that ended in 1492, and he brought with him to the Indian Ocean the uncompromising attitudes of the Christian reconquista. He sacked Kilwa, which had four stone-throwing catapults for its defense, and deposed the sultan in favor of another more amenable to the Portuguese. Further up the coast, Mombasa had some 3700 men of military age and cannon that fired on the Portuguese as they entered the port. The Portuguese, in return, bombarded the town. A Spanish convert to Islam came out and told the Portuguese to leave, that the people of Mombasa were braver than those of Kilwa. That night, Almeida put the town to the torch and in the morning sacked it, killing some 1500 people and taking great quantities of cotton cloth, silk and gold-embroidered textiles as well as valuable carpets. The king of Mombasa wrote to the king of Malindi to warn him of what might befall him: “This is to inform you that a great lord has passed through the town, burning it and laying it waste. He came to the town in such strength and was of such cruelty, that he spared neither man nor woman, old nor young—nay, not even the smallest child…. Nor can I ascertain nor estimate what wealth they have taken from the town. I give you this news for your own safety.”

The new Mamluk fleet built at Suez set out for India in 1507, first fortifying Jiddah and Suakin against a possible Portuguese attack. It put in at Aden, where it received support from the Tahirid sultan, and then, in 1508, crossed the Indian Ocean to the Gujarati port of Diu. There it was joined by local ships supplied by Malik Ayaz, and although the soldiers in the contingent did not have firearms, the combined fleets nonetheless carried out a successful surprise attack on the Portuguese in Chaul. Almeida’s son was killed and the Portuguese routed. In 1509, however, the Portuguese fleet, led by Almeida, defeated the Mamluks off Diu, and another fleet would not be sent against the Portuguese until 1538, this time by the Ottoman Turks.

Thus Almeida had demonstrated Portuguese sea power again—but no secure naval base had yet been obtained. This task fell to Alfonso de Albuquerque, the true architect of Portuguese naval strategy in the Indian Ocean. Succeeding Almeida in 1509, he quickly realized that the Portuguese could not compete on equal terms with long-established Muslim merchants, for there was no market for European exports, and Portugal did not have the liquidity to supply gold and silver on a sufficiently large scale. Albuquerque saw that the only way to protect Portuguese trade in the face of the growing opposition of Indian Ocean principalities and Muslim merchants was to establish a permanent military and naval presence in the region, and this could only be done by securing a permanent naval base. Only then could the key ports be taken, fortified and garrisoned and a monopoly of the maritime trade secured.

|

| Alfonso de Albuquerque understood that Portugal could not compete on equal terms with the established Indian Ocean traders because there was no market for European exports: The only way to tip the scale was to use force, and he led the Portuguese conquests of Goa, Malacca and Hormuz, as well as persistent but unsuccessful attacks on Aden. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY |

As that base, Albuquerque chose Goa, a port on the Malabar coast in the territory of the Sultan of Bijapur, Yusuf Adil Shah. It had a good harbor and was also a center of shipbuilding. The sultan imported horses from Arabia for, like all the inland sultanates, he maintained his power against rivals with cavalry. Control of the horse trade could be used as a weapon. Albuquerque formed an alliance with a Maratha warlord named Timoyya, and together they took the city in 1510. Goa would remain the capital of the Portuguese seaborne empire, the Estado da India, until 1961, when the Indian army occupied it and put an end to four and a half centuries of Portuguese rule.

Albuquerque saw that there were three key emporia in the Indian Ocean: Malacca, Aden and Hormuz, each on a narrow strait controlling access to a major trade route. Malacca was the gateway to the Bay of Bengal, the Spice Islands (the Moluccas) and China. Aden was the gateway to Egypt, North Africa and the Mediterranean. Hormuz controlled access to the Gulf and the overland trade to Iran, Central Asia and the Middle Eastern heartlands.

“Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice,” wrote Tomé Pires, who served at both Goa and Malacca. It was true: Malacca was the collecting point for the spices from the Moluccas, the silks and porcelains of China and all the other rarities that had traditionally been available to Europe only from the hands of Venetian merchants.

In 1511, Albuquerque took the port with a fleet of 16 ships and a force of 700 Portuguese and 300 Malabaris, defeating a Malaccan army of 4000. The ruler fled south to Johor, where together with other refugees he formed a rival state. Albuquerque expelled Gujarati, Bengali and Muslim Tamil merchants from the city. Some made their way to Aceh, which quickly became a center of resistance to the Portuguese. Supplied with cannon by the Ottoman Turks, they built up a navy that shipped Sumatran pepper to the Red Sea by running Portuguese blockades.

In 1513, two years after taking Malacca, Albuquerque laid siege to Aden. He knew that the Mamluks were preparing a second fleet at Suez, and he wanted to strike before Aden received reinforcements. Unlike Malacca, Aden was well-fortified, with high walls and determined defenders who were perfectly aware that not only their livelihoods were at stake, but the security of the Holy Cities and the pilgrimage routes as well. Albuquerque had brought seige ladders wide enough to take six men abreast, but at the battlements they either broke under the weight of the attackers or were pushed off the walls. After a savage battle from dawn to midday, the Portuguese were forced to withdraw. Albuquerque and the survivors of the siege took refuge on the Kamaran Islands, inside the Bab al-Mandab. For a time they harried Red Sea shipping, but sickness among the men finally forced Albuquerque to withdraw.

|

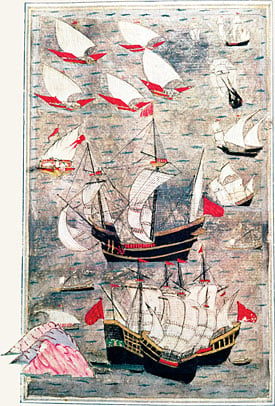

| A Turkish sketch from the 16th century shows the Ottoman fleet, which protected Aden and Jiddah from the Portuguese. By the 1560’s, more spices reached Jiddah than Lisbon. BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

Despite repeated attempts, the Portuguese never succeeded in taking Aden, and their failure meant that Portuguese control of Indian Ocean trade was only partial. Although they sent annual fleets to blockade the Bab al-Mandab, they could not prevent Gujarati ships carrying Sumatran pepper from Aceh from breaking through to Jiddah. By 1545, pepper was once again beginning to arrive in Alexandria, and by 1560, Alexandria was supplying Venice with as much pepper and spices as it had before the discovery of the Cape route to India.

The third key emporium on Albuquerque’s list was Hormuz, which he succeeded in taking with six ships in 1514. Until the joint forces of Shah Abbas and the British East India Company recaptured it in 1622, this port—located on a barren island with no water or wood of its own—was one of the richest cities in the world. The Arab dynasty that Albuquerque defeated continued to rule it as Portuguese vassals.

Jacques de Coutre, a Flemish merchant and soldier serving with the Portuguese, described Hormuz in 1606: “At the trading season during the monsoons, more than 200 large ships come filled with merchandise. Some are loaded with cinnamon from Ceylon, others from Cochin with cloth from Bengal and Coromandel and cloves, nutmeg, mace, sugar and other goods that come from south of Cochin. Other ships come from Makkah and Aden to buy; still others come from Mangalore and Barcelore, loaded with rice.” He lists dozens of goods and trading partners and estimates that the customs duties levied on all this merchandise came to some 100,000 cruzados a year. He also describes the large number of boats that came to Hormuz from the ports of the Arabian coast: Suhar, Julfar, Dubai, Bahrain and al-Qatif.

De Coutre estimates that merchants who traded in Hormuz twice a year made profits of 40 to 50 percent. This sounds a reasonable rate of return, but Portuguese profits on the pepper trade could run as high as 500 percent, and pepper was the principal commodity the Portuguese traded. During the first two decades of the Estado da India, 95 percent of the weight of the cargoes of the great carracks that arrived in Lisbon was pepper, which was valued not only as a condiment but also as a prophylactic against the plague and as an aphrodisiac. As time went on, however, the demand for pepper decreased, and more and more cargo space was devoted to textiles. By de Coutre’s time, pepper had fallen to an average of 10 percent of the cargoes and textiles made up more than 60 percent. A fashion revolution had taken place in Europe; suddenly everyone wanted to wear comfortable, brightly colored cottons and silks and to decorate their houses with oriental tapestries, cushions, hangings and carpets.

|

| Albuquerque’s armada bombards Goa, an event that actually happened the year after the date on this engraving. The impediments in the channel (foreground) may have been defenses against his ships. Goa’s shipyards can be seen to the right of the town, enclosed by a wall that runs down into the channel. BRAUN AND HOGENBERG, CIVITATES ORBIS TERRARUM, 1572 |

De Coutre’s vivid picture of a major entrepôt in which everything was available, from extremely valuable precious metals, textiles and spices to humbler but vital goods like nails and coir for shipbuilding, gives an idea of the amazing range of commodities and the extended trading networks of the major ports.

In all the ports controlled by the Portuguese, Albuquerque instituted the system of the cartaz, a trading licence authorizing a ship to carry cargo. Ships without a cartaz, which of course had to be purchased from the Portuguese port authorities, were fair game. This simple protection racket, plus customs duties and some outright piracy, raised the money to defray part of the cost of manning garrisons and maintaining the navy—as well as purchasing cotton textiles to trade for spices in the Moluccas and for gold and ivory in East Africa. The cartaz system enabled the Portuguese to exercise some control over trading networks that they could not dominate. In time, they raised further revenues by selling concessions for specific maritime trade routes to Asian shipowners. By the mid-16th century Asian merchants were shipping their goods on Portuguese ships and vice versa. And even the Portuguese ships were crewed by men from Arabia, Malabar, Gujarat, Malaysia and Indonesia, with perhaps one or two Portuguese officers. Pidgin Portuguese became the lingua franca of the Indian Ocean ports.

In 1538 the Ottomans sent a huge fleet of 100 ships and 20,000 men down the Red Sea. They occupied Aden and captured a number of Portuguese ships. This Ottoman occupation prevented the Portuguese from threatening either Aden or Jiddah any further, and, by the 1560’s, more spices, largely conveyed in ships from Aceh, were reaching Jiddah than were reaching Lisbon. By the end of the 16th century, the Portuguese had abandoned any attempt to establish a monopoly of trans–Indian Ocean trade, contenting themselves with their control of the sea route to Europe. Many private Portuguese traders operated on equal terms with their Asian partners and competitors, fully assimilated to the constraints of the Indian Ocean trading network.

While the Portuguese were establishing their Estado da India in the Indian Ocean, Cortez and Pizarro were conquering the Aztec and Inca empires. They looted gold almost beyond the dreams of avarice, and it was dissipated almost as quickly as it had been found. Then something extraordinary, almost miraculous, happened. In 1545, in the mountains of what is now Bolivia, in one of the most desolate places on the planet, a mountain of silver was discovered, the cerro of Potosí. The following year, in Mexico, Juan de Tolosa discovered the great silver mines of Zacatecas. The discovery of these vast silver deposits in the New World coincided with the rediscovery of the mercury amalgamation method of silver refining. First used by the Arabs in the 12th century in North Africa, it allowed much greater quantities of silver to be obtained from the ore. By another remarkable stroke of luck, a major deposit of cinnabar—mercury ore—was discovered in 1563 at Huancavalica in Peru. Silver could now be refined in Peru without having to import mercury from Spain.

While the Portuguese were establishing their Estado da India in the Indian Ocean, Cortez and Pizarro were conquering the Aztec and Inca empires. They looted gold almost beyond the dreams of avarice, and it was dissipated almost as quickly as it had been found. Then something extraordinary, almost miraculous, happened. In 1545, in the mountains of what is now Bolivia, in one of the most desolate places on the planet, a mountain of silver was discovered, the cerro of Potosí. The following year, in Mexico, Juan de Tolosa discovered the great silver mines of Zacatecas. The discovery of these vast silver deposits in the New World coincided with the rediscovery of the mercury amalgamation method of silver refining. First used by the Arabs in the 12th century in North Africa, it allowed much greater quantities of silver to be obtained from the ore. By another remarkable stroke of luck, a major deposit of cinnabar—mercury ore—was discovered in 1563 at Huancavalica in Peru. Silver could now be refined in Peru without having to import mercury from Spain.

A river of silver from Potosí and Zacatecas flooded the world. The real de a ocho, the Spanish “piece of eight,” became an international currency that fueled the world economy for more than two centuries. This badly stamped, unmilled coin flooded the economies of the East. Although its abundance inflated prices, the inflation was offset by the fact that silver increased in value the further east it traveled, just as pepper did voyaging west: The Venetians estimated that silver gained 30 percent over its European purchasing power simply by traveling to the Levant. The relative scarcity of silver that had afflicted medieval economies, hampering trade, was replaced by an apparently limitless supply. Then yet another unexpected source of silver was discovered: Japan.

The Ming dynasty of China, angered at the depredations of pirates off their southern coast, who they claimed were supported by the Japanese, outlawed trade with Japan—indeed all maritime trade—in 1480. Tokugawa Japan, which greatly valued Chinese silks and manufactured goods, was left unable to trade directly with China, although smuggling was rife.

Until the beginning of the 16th century, Japan had imported silver. Then, in 1526, the rich mines of Iwamiginzan were discovered. During the 16th and 17th centuries, they produced an average of 32,000 to 40,000 kilograms of silver per year (1 to 1.2 million troy ounces), making Japan the second-largest silver producer in the world.

|

| This detail from a folding namban jin (“southern barbarian screen”) shows Portuguese traders landing in Japan. Though they found Japan by accident, they did so just as Japan had discovered vast deposits of silver and was eager to trade. MUSEU CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN / WERNER FORMAN / ART RESOURCE |

A country with a surplus of silver that was unable to trade with its closest neighbor could not long escape the attention of the Portuguese. They first made contact with Japan by accident in 1543, when a ship blown off course landed on the island of Tanegashima, today the home of the Japanese space program. The local ruler, Tanegashima Tokitaka, bought two arquebuses from the castaways and had them copied, and in 1575 they were used against the Takeda samurai by Oda Nobunaga with devastating effect. This too is an aspect of early “globalization.”

In the event, it was the Portuguese who mediated in the trade between China and Japan. They did this from Macao, not far downstream from Canton, where in 1556 they were granted permission to establish a trading “factory.”

Their acceptance by the Chinese was slow. Indeed, it had been widely believed in the Chinese ports that the Portuguese were cannibals. When the first Portuguese ship put in at Canton in 1513, the Chinese authorities regarded the trade goods aboard with disdain. But with the grant of Macao, the Portuguese were able to greatly extend the geographical and commercial scope of the Estado da India. They brought silver, ivory, ebony and sandalwood from Goa and Malacca to Macao, took Chinese silks and other goods to Nagasaki in exchange for silver, exchanged the silver for gold with Chinese merchants in Macao, and returned to Malacca and Goa with gold, silk, camphor, copper, mercury and porcelain, all in great demand in the Indian Ocean trading network. This trade was especially lucrative because the value of silver was greater in China than in Japan.In 1567, the Chinese, eager for silver, relaxed the ban on maritime trade, although foreign ships were only allowed to visit a few designated ports.

|

| This panel of the so-called “Miller Atlas,” showing the Indian Ocean, was produced in 1519, soon after the expeditions of da Gama, Cabral and Albuquerque. BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

In 1564, the Spanish admiral Miguel López de Legazpi sailed from Acapulco and occupied Cebu in the Philippines; in 1571 he took the city of Manila. Soon an annual galleon was sailing from the Philippines to Mexico with a cargo supplied to Manila by the Portuguese in Macao and, increasingly, by Chinese merchants: Chinese silks, porcelains and manufactured articles as well as spices from the Indian Ocean. The galleons returned from Mexico loaded with silver. Chinese goods were transshipped to Europe from Veracruz, but the local demand for them in Mexico and Peru was so great that in 1631 the Spanish crown banned trade in Chinese merchandise between the viceroyalties to stanch the outpouring of bullion to Manila and protect their own captive market for Spanish textiles. By 1640, the Dutch had entered the Indian Ocean and were importing Chinese and Persian silks via the Cape and underselling the Manila exports. The Manila galleons continued to sail, but now their cargoes were distributed in the New World alone.

The route of the Manila galleons was the final connection in a trading network that now circled the globe. Along these routes, silver and gold flowed to the East and luxury goods to the West, just as they had in classical and early Islamic times.

This flow persisted long after Portuguese power was eclipsed by the Dutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie and the British East India Company in the early 17th century. It did not change substantially until the East India Company became a territorial power, occupying Bengal after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. It did not change irrevocably until the 19th century, when, in a colossal and carefully thought out reversal of fortunes, European manufactured goods, especially textiles, began to flood the East, redressing the West’s trade deficit, recovering liquidity and destroying local economies in the East. And just as the factories of Birmingham and Manchester destroyed the Indian textile trade, the steam- ship defeated the monsoon.

|

Historian and Arabist Paul Lunde studied at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and specializes in Islamic history and literature. He is the author of Islam: Culture, Faith and History. With Caroline Stone, he has translated Mas‘udi’s Meadows of Gold and—forthcoming this fall from Penguin—Travellers From the Arab World to the Lands of the North, a collection of travel accounts. Lunde is a longtime contributor to this magazine, with some 60 articles to his credit over the past 33 years, including special multi-article sections on Arabic-language printing and the history of the Silk Roads, and the theme issue “The Middle East and the Age of Discovery” (M/J 92). He lives in Seville and Cambridge, England, and is working on an Internet project to map pre-modern Eurasian cultural and intellectual exchanges. He can be reached at paullunde@hotmail.com. |

< Previous Story