Written by John Lawton

Photographed by Tor Eigeland

|

|

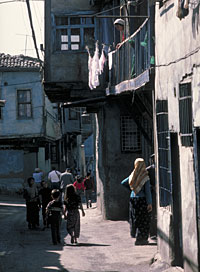

elching smoke, our Silk Roads "special" sped shrieking through the Asian suburbs of Istanbul, past knots of wide-eyed, waving children fascinated by the unusual sight and sound and smell of an enormous black coal-fired steam locomotive. It was an exciting start to an extraordinary journey. In the weeks that followed we were to travel the longest "road" on earth: 9,600 kilometers (6,000 miles) across Turkey, the southern Soviet Union and China, from one end of the ancient Silk Roads to the other.

elching smoke, our Silk Roads "special" sped shrieking through the Asian suburbs of Istanbul, past knots of wide-eyed, waving children fascinated by the unusual sight and sound and smell of an enormous black coal-fired steam locomotive. It was an exciting start to an extraordinary journey. In the weeks that followed we were to travel the longest "road" on earth: 9,600 kilometers (6,000 miles) across Turkey, the southern Soviet Union and China, from one end of the ancient Silk Roads to the other.

En route, we would see unique sights: Cappadocia's fantasy landscape of "fairy chimneys" and China's Great Wall. We would visit legendary caravan cities - Bukhara, Samarkand and Kashgar - and meet exotic people: daring Kazak horsemen and dazzling Uzbek dancers. We would cross unfriendly frontiers normally closed, and be feted in cities usually forbidden to foreigners.

The chartered trains, airplanes and convoys of buses of this remarkable tour would - like magic carpets - whisk us from season to season, century to century as we traversed Central Asia's sun-scorched steppes and struggled through its snow-choked mountain passes in the footsteps of merchants like Marco Polo, along the migration routes of entire peoples, and on the paths of the armies of Alexander the Great, Tamerlane and Genghis Khan.

Highways that helped shape history, the Silk Roads were conduits for conversion as well as for commerce and conquest: Two of the world's most widespread religions, Buddhism and Islam, were disseminated by way of the Silk Roads by monks in saffron robes and by pious Arab merchants (See Aramco World, July-August 1985).

Craftsmen, scholars, entertainers and official emissaries from far-off lands traveled the Silk Roads too, and many languages were spoken, many cultures blended, in the glittering cities that grew up along them. Inevitably these routes formed a cultural causeway carrying new ideas, new philosophies, new artistic styles over vast distances.

|

Some of the world's basic technologies - among them printing and papermaking - were transmitted along these channels of communication. And many fruits and flowers, among them grapes and pomegranates, roses and chrysanthemums, were transplanted via the Silk Roads. Even Chinese acrobats trace their origins back to the arrival of tumblers from the Levant.

At the western end of this great highway of human intercourse stood Constantinople, center - and emporium - of the Christian world. It became the capital of the Roman empire when Constantine, the empire's first Christian emperor, moved his court and administration there in AD 330 to escape declining Rome, its economy crippled and its morals corrupted, some claimed, by imported luxuries - especially silk. Within 200 years the former Greek trading post - known as Byzantium until Constantine renamed it for himself - became the most prestigious city in Europe; for almost a millennium it was the main terminus of the Silk Roads. It was here that we began our journey.

|

Although the Silk Roads withered and died, the imperial grandeur of Constantinople - captured by the Turks in 1453 but officially renamed Istanbul only in 1926 - remains stamped indelibly on its skyline of mosques, towers and palaces banked magnificently up the hills above the triple confluence of the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara and the Golden Horn. And the city still owes much of its importance to trade: Oil tankers and container ships steam constantly up and down the Bosporus, which links Russia's Black Sea ports with the Mediterranean, while high overhead, convoys of 18-wheeled trucks carrying Middle East-bound cargos (See Aramco World, November-December 1977) rumble over the mile-long suspension bridge linking Europe and Asia.

Theoretically, that's how one goes from Europe to Asia: by simply crossing the Bosporus. In practice, though, the suburbs on one side are much the same as on the other; the continents overlap and the boundary is a far more subtle one. Somewhere that night, as we trundled across Anatolia, we slipped insensibly into Asia.

Over the centuries Anatolia, or Asia Minor, has been both bridge and battleground between East and West. The Persians were the first power to master it all, defeating Croesus, the proverbially wealthy king of Lydia - he was one of the first rulers to mint his own coins - in 546 BC. Next, like a great sword-thrust from the west, came Alexander, who crushed the Persians at the battle of Issus in 333 BC and occupied the whole of Anatolia in the reverse direction.

|

Later Rome and Parthia waged a long and bitter struggle over Anatolia. The Romans triumphed in the end, but by the sixth century their rule had given way to that of Byzantium. Then the Arabs, and later the Seljuq Turks, erupted from the East and Anatolia became the battleground of a new struggle.

At the battle of Malazgirt, in AD 1071, the Seljuq Turks defeated the Byzantine armies and occupied central Anatolia. But they too succumbed in turn, to the Mongols. When the Mongol tide ebbed, about the 14th century, another tribe of Turks, the Osmanli or Ottomans, suddenly began expanding. They smashed the remnants of Byzantium and established an empire that ultimately stretched from the Adriatic to the Arabian Gulf (See Aramco World, July-August 1987). It too finally collapsed in the holocaust of World War I, but the Turks hung on to Anatolia, which together with European Thrace forms modern Turkey.

It was a fitful first night as we crossed this historic land in the strange and unsteady surroundings of a train compartment. But we were lapped in luxury compared with the hardships of the traders who once traveled the Silk Roads: By day, they walked alongside their pack animals - camels, mules, yaks or horses, depending on the terrain - and they slept most nights under the stars. In the mountains, where avalanches could bury an entire caravan, they were prey to frostbite and snow blindness; in the desert, where sandstorms could pin them down for days, they were tormented by heat and thirst.

|

|

|

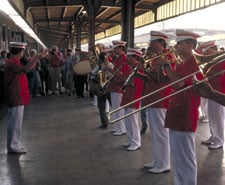

| Brass bands greeted the Silk Roads "special" at Istanbul, Ankara and Kayseri. |

There were human enemies too: bandits who preyed on the richly-laden caravans. For safety, the merchants often joined together in convoys, sometimes with as many as 1,000 camels. The richest among them maintained men at arms; the less wealthy would pay for the privilege of being under their protection.

But despite all the differences of detail between their camel caravans and our mechanized one - a powerful locomotive, seven sleeping cars, two restaurant cars and two Pullman coaches - the basic rationale behind both was the same: We were traveling in groups for convenience and economy.

In fact, in our case, the journey would have been virtually impossible as individual travelers. For although some former Silk Roads cross-border links are being reforged, one can only travel across them by making difficult simultaneous prior arrangements with Turkish, Soviet and Chinese authorities - and then in closely guarded groups on very rare occasions.

Thus we, for example, were only the third group to make the Silk Roads journey end-to-end across these borders in recent years. And although it has been possible to cross between Pakistan and China via the Karakoram Highway since 1986, even this route was blocked by avalanches at the time of our journey.

Even so, this trickle of modern travelers probably amounts to more people than made the entire journey in the great days of the Silk Roads. For trade between China and the Mediterranean has almost always been carried out in stages: No individual caravan made the entire journey; goods changed hands many times before they reached their final destination.

|

|

|

| Folk dancers greeted the Silk Roads "special" at Istanbul, Ankara and Kayseri. |

This was not because merchants did not want to make the whole journey, but because the countries straddling the Silk Roads - eager to protect their earnings as middlemen - refused to let them pass. Only in the 14th century, when the Mongol empire ruled almost the whole length of the Silk Roads, were merchants like the Polo family able to make the entire trip.

At their zenith, in AD 200, the Silk Roads and their western connections over the Roman road system constituted the longest overland trade route on earth: a travel distance of some 12,800 kilometers (8,000 miles) from Cadiz on the Atlantic coast to Shanghai on the Pacific Ocean. From the main routes subsidiary ones branched out into other networks covering North Africa, Arabia, Russia and India.

By Roman times these routes were already ancient pathways to profit: Lapis lazuli was brought west from Afghanistan to Sumer and Egypt 5,000 years ago; Assyrian caravans carried tin from Anatolia to Mesopotamia in the second millennium BC; and at the turn of the fifth century BC the Persians built a network of roads to link the far-flung marches of their empire, which stretched from the River Indus to the Aegean Sea.

The most famous of these was the Royal Road, a 2,500-kilometer (1,600-mile) all-weather highway from Susa, the Persian capital, across Mesopotamia, Syria and Anatolia to Sardis.

Like modern roads, it bypassed big cities to avoid delays, and although camel caravans took some 90 days to make the journey, relays of royal messengers on fresh steeds, riding from one to another of 100 fortified stations, could do it in nine. These couriers, wrote Herodotus, were "stayed neither by snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness from accomplishing their appointed course" - a description adapted as a motto by the United States Postal Service and still invoked today.

Following a similar route, our train had climbed steadily upward during the night, depositing us at dawn on the Anatolian Plateau - a country of rolling rust-colored hills and fertile purple-and-green plains punctuated by compact mud-brick villages and lines of lithe poplar trees. At its center stands Ankara - not much more than a primitive country town when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern Turkey, set up headquarters there in 1920. Now it is a metropolis of 3.3 million people.

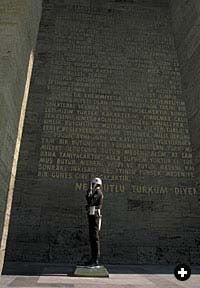

|

Ankara has been a natural stronghold since Hittite times - its citadel even resisted the armies of Tamerlane - and from its fastness Atatürk turned military humiliation into victory: He repulsed the Greeks who, with British backing, were attempting to recapture what had once been the Anatolian provinces of the Byzantine empire, and restored to his demoralized and dismembered country its independence and its pride.

Today Ankara's ancient citadel and the massive, colonnaded yellow-limestone mausoleum where Atatürk is buried face each other across the city from atop two small hills. Below, built from 25 different varieties of Anatolian marble, stands Turkey's enormous parliament building. It took 21 years to construct and was completed in 1960, the very year in which an army coup briefly abolished the parliamentary regime. It was said that the sight of such a stupendous building standing empty prompted the generals to restore democracy more quickly than they might otherwise have done.

Having frequently reported on Turkey's politics from Ankara as a foreign correspondent, I declined the offered city sightseeing tour and retired to the railroad station's busy barbershop: Shaving is hazardous on a moving train. There, buried beneath mounds of white shaving foam, I eavesdropped on fellow customers' views of Turkey's latest political events.

Refreshed and back on board, we followed the Royal Road east - at a pace not much faster than that of the couriers of the Persian kings. For although we were now pulled by a smart new red-and-white diesel locomotive, it took us 10 hours to cover the 300 kilometers (188 miles) between Ankara and Kayseri, a city that has been a major East-West trading center since Assyrian times.

|

The Assyrians, who inhabited northern Mesopotamia in the second millennium BC, established great trading outposts in Anatolia which they called karums. Among these, the karum of the central Anatolian city-state of Kanesh, 22 kilometers (14 miles) northeast of Kayseri, was the center. Using routes through Kanesh, the Assyrian merchants imported tin and cloth by caravans of 200 to 250 donkeys and sold their goods to the indigenous Hattian people for silver and gold. Thousands of Assyrian cuneiform tablets - unearthed in the foreign trading colony built adjacent to the palaces of the princes of Kanesh - provide details of these transactions.

International trade remained the backbone of the central Anatolian economy until medieval times. To safeguard it, the pragmatic Seljuq sultans and their viziers built a network of caravanserais - fortified inns with accommodation for merchants, their goods and their pack animals - in the 13th century. The Persian word caravanserai comes from a root meaning "to protect"; the Turkish form, kervansarayi, means "caravan palace."

Even today the vast castle-like profiles of the caravan-palaces punctuate the endless skyline of the Kayseri plain, their large, richly-carved portals symbolizing the relief and security they once offered in the midst of a long and hazardous journey.

One of the best examples of this type of Seljuq civic architecture is Sultan Han, built in 1234 by Sultan Alaeddin Kaykubad, which lay on our route on the Kayseri-Sivas road. On three sides of its courtyard are chambers that served as private bedrooms, storerooms and a bath house. Men and their saddle horses were accommodated in a large central hall. The fourth side is occupied by deep open arcades that housed camels and carts. And in the middle of the courtyard stands a mosque, its entire surface adorned with beautiful ornaments of Seljuq art.

|

Like the medieval merchants who stopped here to rest themselves and their animals, repair their equipment and polish their weapons, we too checked into a hotel in Kayseri to shower, get a sound night's sleep and have our laundry done. But, as happened at most of the hotels we descended on en route, the arrival of our large party, all trying to do the same thing at once, overtaxed facilities: Elevators seized up, hot water ran out and laundry came back in promiscuous confusion.

With such a large group, mealtimes were also chaotic, and frequently sent us in search of nearby neighborhood restaurants unaffected by our group presence. In Kayseri we had a delicious lamb kebab covered in fresh yogurt (See Aramco World, March-April 1988). We also stocked up on the local delicacy, pastirma - dried beef cured in hot spices and coated with a pepper paste - as our contribution to "corridor parties" on the train.

|

By the next morning the Kayseri hotel elevator was working again - after its fashion. "It's just not stopping at any of the floors," explained one bemused matron as we followed her down the stairs.

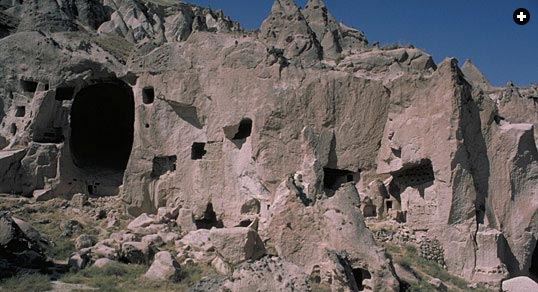

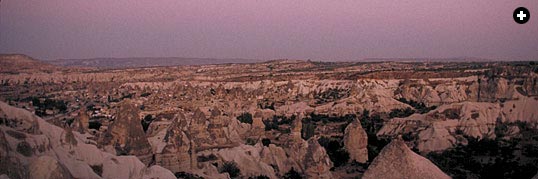

It was the first of many darkened stairways and precipitous passages we climbed that day, for we visited the subterranean cities and cave churches of the lava-filled basin of Cappadocia (See Aramco World, May-June 1971). Located west of Kayseri between two extinct volcanos, Cappadocia's soft rock has been fissured by earthquakes and honeycombed by erosion into thousands of crooked pinnacles like rows of great white whales' teeth many stories high.

Local people named them "fairy chimneys" because they thought the weird formations were made by magic, and early Christians hollowed out the cones to build more than 200 churches inside. Shaped internally like conventional buildings, with arches and columns apparently supporting vaults and domes, they are in fact spaces cut out of the rock.

|

| The "fairy chimneys" inside which early Christians built frescoed churches, and Kaymakli underground city. |

The Christian community lived in secret underground cities nearby. Invisible from above, the cities comprise a labyrinth of passages, extending as many as eight stories deep into the rock. On both sides of these tunnel "streets" tiny dwellings, storerooms and communal kitchens were hewn out where, in the 11th and 12th centuries, thousands of people are thought to have worked and lived.

Two of the vast underground tenements have been made safe and fitted with electric lights so the adventurous can explore the strange, subterranean world of these troglodyte Christians who, for almost 2,000 years, kept their faith and their churches intact, decorating the latter with beautiful frescoes.

Now, however, the same erosive process that helped form the churches is slowly destroying them: The rough stone outer walls of the hollowed-out cones are collapsing, leaving their gilded interiors exposed. Without a major international restoration effort, say experts, these unique churches will simply disappear.

That night fires set by farmers to burn off wheat stubble were spread spectacularly across the hillsides, like the tongues of glowering lava that filled the Cappadocian basin thousands of years ago, long before even the Royal Road coursed across the Kayseri plain en route to the present Turco-Syrian border.

This border was frontier country, too, in Rome's long war with the Parthians, and it is here that the Romans - according to the historian Florus - got their first sight of silk: Mounted Parthian archers unfurled brilliantly-colored silk banners during the battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, dazzling and terrifying the Roman legionnaries-already disoriented by the Parthians' "parting-shot" tactics of firing as they withdrew - and contributing to their rout.

Within seven years of that event, according to an account written by Dionysius Cassius, silk canopies were used to shelter spectators during Julius Caesar's triumphal entry into Rome. Silk cloth quickly became indispensable in every great Roman household, and soon hundreds of caravans laden with bales of silk were lumbering along the Silk Roads, to satisfy Rome's insatiable demand.

< Previous Story | Next Story >