he "Silk Road Express," as our mechanized caravan had been dubbed, was making slow progress. For although modern highways and railroads have replaced tortuous caravan trails along the Silk Roads, these links too can be tenuous in the face of natural or human forces. The railroad traversing eastern Turkey, for example, is only a single track - and now it was blocked by a derailment far up ahead, beyond Sivas.

he "Silk Road Express," as our mechanized caravan had been dubbed, was making slow progress. For although modern highways and railroads have replaced tortuous caravan trails along the Silk Roads, these links too can be tenuous in the face of natural or human forces. The railroad traversing eastern Turkey, for example, is only a single track - and now it was blocked by a derailment far up ahead, beyond Sivas.

But then, this never was one of the easiest of the Silk Roads; rather, it was a mountainous diversion to be used when both the steppes to the north and the deserts to the south were impassable.

Although the label "silk road" is widely used, there never really was a single road, but rather a shifting network of roads, desert trails and mountain tracks that were used more heavily or less as empires and markets flourished or declined, or as merchants sought safer, more practical detours in time of war, plague or famine.

|

| The "Silk Road Express" on its tortuous run to Erzurum. |

Similarly, we now struck off through the mountains of eastern Turkey, across the Soviet republics of Georgia and Azerbaijan and over the Caspian Sea, to avoid the conflict between Iraq and Iran.

Because of delays caused by the derailment, it was after dark when we pulled into Sivas, on the eastern fringe of the Anatolian Plateau. But even by flashlight, the splendid sculptured stonework of the great religious colleges of Gökmedresse and Çifte Minareli made it clear why these buildings are considered two of the finest works of medieval Turkish art.

|

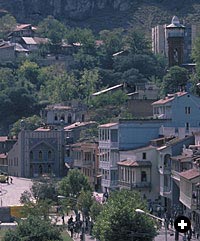

| Erzurum was once a key caravan crossroad. |

|

| Erzurum and a few of its senior citizens. |

At Sivas, like the merchants of old, we picked up a security escort. Ours comprised four Turkish plainclothesmen, small arms bulging under smart suits, who accompanied us through eastern Turkey, inhabited by tribal Kurds who occasionally threaten travelers. During that night we passed the derailment, edging past freight cars toppled crazily by the track. But the delay did have its compensations: We made most of the twisting, uphill run to Erzurum by daylight, instead of in the dark, as scheduled, powering between high mountains, weaving alongside tumbling river torrents and bursting out of black tunnels onto open plains.

The seasons, as well as the scenery, changed too: Here leaves of the ubiquitous poplars were already an autumnal gold, and smoke curled lazily from the chimneys of farmhouses whose flat roofs were piled high with fodder for the fast-approaching winter.

Erzurum, situated amid high mountains at 2,000 meters (6,500 feet), was busy too preparing for winter: Hundreds of shiny metal stoves were on sale on sidewalks swept by icy winds. In smoky, overheated coffee houses, Turks with scrub-brush moustaches drank black tea, a sugar lump held beneath the tongue to sweeten the strong brew.

Unofficial capital of eastern Turkey, Erzurum was once a major caravan crossroads. From here routes radiated west to Ankara and Istanbul, north to Trabzon on the Black Sea coast, and southeast past Mount Ararat - legendary resting place of Noah's Ark - to Tabriz in today's Iran.

Yet another road, the one we were traveling, arched northeast between the Black and Caspian Seas to Tbilisi in Georgia. From here, merchants either headed east to Baku and took ship across the Caspian Sea, or crossed the Caucasus Mountains to the north to join the Eurasian Steppe Route.

This route, which traversed the steppes of southern Russia and Kazakstan, was the oldest of the Silk Roads, according to Ma Yong, vice-chairman of the Chinese Society for Central Asia. Nomadic tribes retreating westward before the pressure of the Huns carried silk with them, and the cloth found its way to Europe at some time between the sixth and fifth centuries BC: Silk fabrics have been found in graves of this period in Germany, Luxembourg and Greece, as well as in the Altai region of the USSR. Yet this tribal population shift could hardly be described as a real trade route.

The first trade in silk was conducted by Chinese envoys, who took it with them on diplomatic missions to Central Asia as "gifts" - but in fact expected a counter-gift of similar value and desirability in return: Failure to receive the return gift, indeed, sometimes led to war.

Han China and Parthian Iran established commercial relations in 105 BC, exchanging "gifts" of silk for acrobats and ostrich eggs. Thus, not quite 50 years later, the Parthians were able to dazzle the Romans with their silken banners.

Even more important, by blocking direct contact between China and Europe, the Parthians were able to monopolize the silk trade and amass great fortunes selling silks to the West.

|

| Pomegranates at Tbilisi market typify the religions, plants and art forms that spread via the Silk Roads. |

So zealously, in fact, did these middlemen and their successors, the Sassanians, guard their monopoly that, although great quantities of silk were sold in the Roman and Byzantine empires, no one in the West seems to have had any notion where it had come from. It was not until the seventh century that a European writer, Theophylactus Simocatta, betrayed even a remote knowledge of the Chinese Empire.

Silk arrived from China across the Iranian plateau via Rhagae, near modern Tehran, and Ecbatana, now Hamadan, and was transported west from the great Mesopotamian cities of Babylon, Seleucia and Ctesiphon, near modern Baghdad, along the Euphrates and across northern Syria to Antioch - today's Antakya - at the eastern end of the Mediterranean.

From Antioch, the silk was either shipped directly to Rome or sent south to be dyed and woven at Tyre or Sidon; to serve these latter ports, a more direct route was opened to the Mediterranean, across the Syrian desert by way of the oasis city of Palmyra. These were known as the Great Desert Routes.

Another route, developed by the Byzantines to bypass the Persian middlemen occupying Mesopotamia, curved northwest from Ecbatana, between Lake Urmia and the Caspian Sea, to Tabriz and Erzurum. And although today Erzurum's caravanserais serve different purposes - one has been converted into workshops for jewelers - long-distance truck drivers still stop in the city en route to Iran.

Erzurum also serves another age-old purpose. Formerly a Byzantine outpost guarding against the Turks, it is now an outpost of the Turks against the Russians: It is the headquarters of the Turkish Third Army, which protects NATO's southeast flank against the forces of the Warsaw Pact. That night, as we advanced slowly towards the Turco-Soviet border, we passed trains loaded with jeeps, artillery, armored cars and troops in full battle gear.

We awoke the next morning on the edge of no-man's-land. A layer of freshly fallen snow covered the hill overlooking the frontier. The ruins of an old fortress were silhouetted against the skyline, and barbed-wire fencing, strung between steel watchtowers, stretched off into the distance on both sides of the railroad track. There was little sign of human activity. A road across the border was completely overgrown with grass.

A lone Turkish foot patrol stopped for a chat. "People here live cooped up like chickens," the soldiers told our cheery conductor Ibrahim. "It's so cold in winter they don't stick their heads out of their houses until spring."

A Soviet train rolled slowly over the border. The Turkish train moved forward to meet it. They stopped on opposite sides of a platform and, lugging our baggage, we switched from one train to the other. For security reasons, the Turkish and Soviet railroad tracks are of different gauges, and so are all the dimensions of the rolling stock. This meant a wobbly climb up a wooden plank from the Turkish-built platform into the Soviet train. Once aboard, we were confirfed to our sleeping compartments until stringent border formalities were complete.

|

|

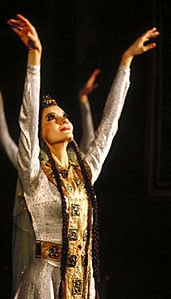

| Georgian dancers. |

More fences lined the Soviet side of the frontier. As our train slipped through them into the USSR, Soviet officials worked their way from compartment to compartment checking passports, counting foreign currency and flipping through any literature we carried - twice. And to complete the border formalities, two men in blue overalls probed the far corners of each compartment with flashlights.

Officially we were now back in Europe: the Republic of Georgia is the southernmost region of the European section of the Soviet Union. It is also traditionally Christian, and cone-roofed churches, most of them unused, now replaced the domes and minarets of Muslim Turkey.

There were other noticeable differences too. Although only a short distance separates Georgia and eastern Turkey, they are economically worlds apart: The former is prospering under Soviet rule, while the latter remains an economic backwater of the Turkish state.

The Soviet train was new and impersonal, and the passengers somewhat subdued after the tedious border crossing. But large quantities of caviar and warming drinks served by cheerful Georgian waitresses soon had spirits restored so well that, detraining at Tbilisi, several couples waltzed to the welcoming music from the platform to buses that whisked us all - with police escorts - to our hotel.

Here, more food, drink and music awaited us - the latter appropriately including Billy Strayhorn's famous "Take the 'A' Train."

Although one of the smallest of the Soviet Union's 15 republics, Georgia is richly and diversely endowed with fertile land and contrasting scenery ranging from the subtropical Black Sea shore to the icy crests of the Caucasus.

|

| A mosque dominating the carefully restored old quarter of Tbilisi. |

It was in Georgia, according to legend, that Jason and the Argonauts found the fabled Golden Fleece, and the capital, Tbilisi, reflects the republic's less mythical economic and cultural riches.

Its main streets and squares are dominated by theaters, libraries and academies, and the embankment of the Kura River, which cuts through its center, is lined with sculpture and statues. Its traditional, ornate balconied buildings, clinging to the steep banks of the river, have been tastefully restored, and even the modern housing complexes that spill out over the surrounding hillsides are impressive.

We skipped meals in the crowded, cavernous restaurant of the Iveria Hotel, a soulless, multistory complex run by the state agency Intourist, and ate spicy Georgian sausages instead: lunch at a riverside buffet and dinner in a cheery cellar restaurant, its walls covered with paintings of Tbilisi's favorite cartoon character, a mythical street-sweeper created by the Georgian painter Pirosmani.

Marco Polo described Tbilisi, in the 13th century, as a "fine city of great size" where "silk and many other fabrics" were woven. Most of this silk reached Tbilisi by way of the ancient Eurasian Steppe Route, the merchants' favored route when the Mongols were masters of the normally dangerous steppes. For although history remembers them mainly as marauders, the Mongols imposed within their empire - which included China, southern Russia and Central Asia - a respect for law and order that was absolute. French historian Louis Boulnois quotes a saying that "a girl could walk across [the empire] from one end to the other bearing a golden dish upon her head without being molested."

The wide, flat steppelands were also much easier to cross than the mountains and deserts to the south. Describing a journey across the steppes, 15th-century Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta took his ease. "Everybody eats and sleeps in his wagon," he wrote, "while it is actually on the move……"

But incessant warfare and raiding by the nomad tribes who swirled around the heart of Asia kept this route closed for most of the time. Merchants therefore usually took other routes: either the Desert Routes to the south, or, the one that we now took, east to Baku and across the Caspian Sea to Central Asia.

Forests of derricks and rocking "grasshopper" oil pumps line the rail route through what was, until the discovery of petroleum in the Middle East, the world's largest oil field, on the western shores of the Caspian Sea. It is also among the world's oldest: Oil has been drawn from its wells since the fifth century.

Today, over 100 nationalities live in nearby Baku - capital of the Republic of Azerbaijan - attracted by work in the oil fields. Their numbers make the city the fifth-largest in the USSR, its imposing modern buildings rising up the slope of the natural amphitheater surrounding the Bay of Baku.

A short bus ride from the city, at Surakhany stands a deserted Zoroastrian temple, its ceremonial fires - which form part of the religion's ritual - still burning.

The ancient pre-Islamic religion of Persia, emphasizing the contending forces of evil and good, Zoroastrianism was founded in the sixth century BC by the reformist prophet Zoroaster in an attempt to unify worship under one god. The religion is still practiced in isolated areas of the world, most notably in India. It spread east along the Silk Roads, just as the Buddhist and Muslim faiths did later.

Two other religions - Manicheism, a blend of Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Christianity, and Nestorianism, a Christian sect whose adherents believed that Jesus was two persons, one human and one divine - also spread to China via the Silk Roads.

Indeed, it was two Nestorian monks who, in one of the earliest feats of industrial espionage, are said to have smuggled the secret of silk manufacture from China to the West: They concealed silkworm eggs, whose export the Chinese forbade, in hollows in their staffs, and traveled in winter so the eggs would not hatch out.

Although their audacious action revealed the Chinese "secret" of sericulture and broke the Persian monopoly of the silk trade, it had little effect on economic and cultural exchanges along the Silk Roads. By the seventh and eighth centuries, in fact, these exchanges had reached unprecedented heights, due principally to the prosperity and power of the Tang dynasty in the East, the Byzantine Empire in the West, and the Arab hegemony in between.